What were the most popular Native American sports and games. How did these activities vary across different tribes and regions. What cultural significance did these games hold for indigenous communities. How have these traditional sports evolved over time.

The Diversity and Significance of Native American Sports

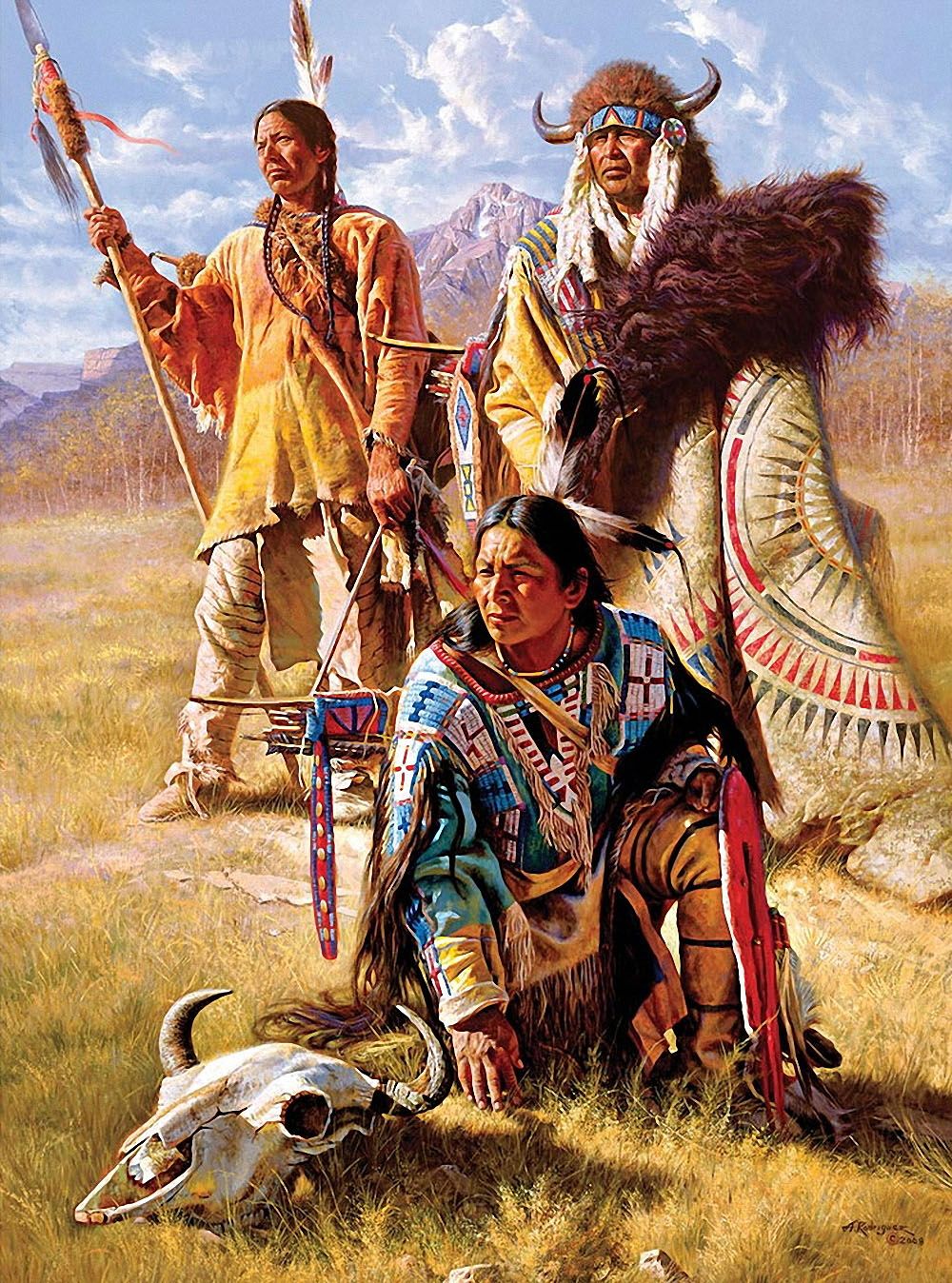

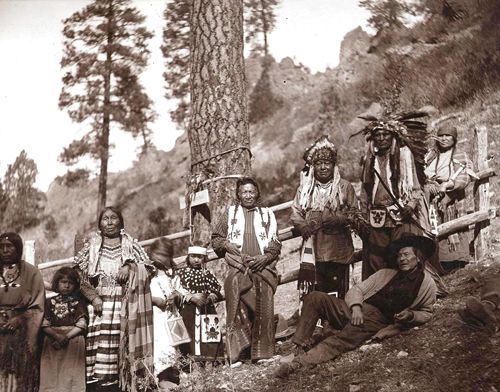

Native American cultures, despite their vast diversity, shared a common appreciation for sports and games. These activities were not merely pastimes but often held deep cultural and religious significance. Many games were widespread across different tribes, with rules varying slightly from one region to another. Interestingly, these sports were frequently incorporated into religious ceremonies, highlighting their spiritual importance.

One of the most striking aspects of Native American sports was the practice of heavy betting, which was common in most games. This suggests that these activities were not only about physical prowess but also served as a means of social interaction and economic exchange within communities.

Lacrosse: The Iconic Native American Sport

Among the various Native American sports, lacrosse stands out as the most renowned. This game, which has gained international popularity in modern times, has its roots deeply embedded in indigenous cultures.

Geographic Distribution of Lacrosse

Lacrosse was particularly prevalent among tribes along the Atlantic seaboard and around the Great Lakes. However, its popularity extended far beyond these regions, with variations of the game being played in the South, on the plains, in California, and even in the Pacific Northwest. This widespread distribution underscores the game’s appeal and cultural significance across diverse Native American communities.

Equipment and Gameplay

The equipment used in traditional lacrosse was both functional and artistic. The ball, a crucial element of the game, was typically made of either wood or buckskin. Players used curved rackets with nets on one end to catch and throw the ball. The goal, which varied in structure depending on the region, was usually marked by two poles, although some areas used only one.

J. G. Kohl, a white traveler who examined lacrosse equipment in Wisconsin in 1860, was particularly impressed by the craftsmanship involved. He noted the fine carving of crosses, circles, and stars on a white willow ball, highlighting the artistic elements incorporated into the sport’s equipment.

Scale and Significance of Lacrosse Matches

Lacrosse matches were often grand events that brought together large numbers of people. Games could pit village against village or tribe against tribe, with hundreds of players participating. The scale of these events is evident in Kohl’s claim that the prizes offered in these games could reach a value of a thousand dollars or more, a significant sum for the time.

Shinny: The Native American Field Hockey

Another widely popular Native American sport was shinny, a game that bears similarities to modern field hockey. This game showcased the inclusive nature of many Native American sports, with participation varying across genders and tribes.

Gender Dynamics in Shinny

While shinny was predominantly played by women, it wasn’t exclusively a female sport. In some regions, particularly on the plains, men also participated. The Sauk, Foxes, and Assiniboine Indians took this inclusivity a step further, with men and women playing together. The Crow tribe had an interesting variation where teams of men competed against teams of women, highlighting the dynamic gender roles in Native American sports.

Geographic Spread and Equipment

Shinny’s popularity spanned across various regions, including the East, the plains, the Southwest, and the Pacific Coast. The game was played with a ball or bag, often crafted from buckskin, which players hit with sticks curved at one end. These implements were often decorated with paint or beads, adding an artistic element to the sport.

Variations in Field Size and Rules

The playing field for shinny varied dramatically in size depending on the tribe. Among the Miwok Indians, the field was a modest 200 yards, while the Navajos played on fields stretching a mile or more. The objective was consistent across variations: to hit the ball through the opponent’s goal. Players could kick the ball or hit it with their stick but were not allowed to touch it with their hands.

Snow-Snake: A Winter Sport of Skill and Precision

In the colder regions of Native American territories, snow-snake emerged as a popular winter sport. This game showcased the adaptability of Native American sports to different climatic conditions.

Basic Concept and Variations

While the rules of snow-snake varied significantly across different tribes, the basic concept remained consistent. The game involved sliding darts or poles along snow or ice, with the goal of achieving the longest distance. The projectiles used in snow-snake ranged from small darts just a few inches long to impressive javelins up to ten feet in length.

Gender Participation and Tribal Variations

Like many Native American sports, snow-snake had different gender participation rules depending on the tribe. Among the Crees, who played a variant where the dart had to pass through snow barriers, only men participated. In contrast, the Arapahos allowed adults and children to play, with girls being the most common participants.

Hoop and Pole: A Test of Accuracy and Skill

Hoop and pole was another widespread game in Native American cultures, showcasing the diversity and complexity of indigenous sports.

Gameplay and Equipment

The basic premise of hoop and pole involved rolling a hoop along the ground while players attempted to knock it over with spears or arrows. The hoop, typically small and ranging from three inches to a foot in diameter, was often intricately designed. Some versions featured an open hoop, while others had cords or a net stretched across it.

The materials used for the hoop varied, including wood, corn husks, stone, and even iron. Many hoops were decorated with paint or beads, adding an artistic element to the game. The scoring system was based on how the hoop fell when hit by the pole, adding an element of chance to the game.

Participant Numbers and Gender Roles

Hoop and pole was most commonly played by two men, although some variations allowed for more participants. This game, like many others in Native American cultures, had specific gender roles associated with it, typically being a male-dominated sport.

The Apache Variation of Hoop and Pole

A particularly interesting variation of the hoop and pole game was observed among the Mescalero Apache in the 1860s by Col. John C. Cremony. This version of the game provides insight into the complexity and cultural significance of Native American sports.

Equipment and Setup

In the Apache version, the poles were approximately 10 feet long, smooth, and gradually tapered like a lance. These poles were marked with divisions throughout their length, each division stained in different colors. The hoop, made of wood and about 6 inches in diameter, was also divided similarly to the poles.

Gameplay and Scoring

The game was played on a specially prepared ground, with grass removed to create a smooth, firm surface about a foot wide and 25 to 30 feet long. Players would roll the hoop forward and then throw their poles after it, aiming to make the hoop fall on their pole. The scoring system was based on where the hoop fell on the pole, with the butt end of the pole ranking highest in value.

Cultural Significance and Gender Restrictions

Interestingly, this version of the game had strict gender restrictions. No woman was permitted to approach within a hundred yards while the game was in progress, highlighting the complex gender dynamics in Native American sports and cultural practices.

The Evolution and Legacy of Native American Sports

The rich tapestry of Native American sports and games offers a fascinating glimpse into the cultural, social, and spiritual life of indigenous communities. These activities were far more than mere pastimes; they were integral components of Native American society, serving multiple functions:

- Physical fitness and skill development

- Social bonding and community cohesion

- Cultural expression and preservation

- Spiritual and ceremonial significance

- Economic exchange through betting practices

The diversity of these games across different tribes and regions demonstrates the adaptability and creativity of Native American cultures. From the widespread popularity of lacrosse to the regional variations of games like snow-snake, these sports reflect the environmental and cultural diversity of indigenous North America.

Many of these traditional games have evolved over time, with some, like lacrosse, gaining international recognition and becoming popular modern sports. Others have been preserved and revived as part of efforts to maintain Native American cultural heritage.

Impact on Modern Sports

The influence of Native American sports extends beyond their original cultural contexts. Several modern sports draw inspiration from or have roots in these traditional games. For instance:

- Lacrosse has become a popular international sport, with professional leagues in North America.

- Field hockey shares similarities with the Native American game of shinny.

- The concept of using sticks to manipulate a ball or object, seen in many Native American games, is a fundamental aspect of numerous modern sports.

Cultural Preservation and Revival

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in preserving and reviving traditional Native American sports. This revival serves multiple purposes:

- Maintaining cultural identity and heritage

- Promoting physical fitness and community engagement among Native American youth

- Educating the broader public about Native American history and culture

- Fostering inter-tribal connections and cultural exchange

Many tribes now organize events and tournaments featuring traditional games, often as part of larger cultural festivals or gatherings. These events not only preserve ancient traditions but also adapt them to contemporary contexts, ensuring their relevance for new generations.

Educational Value

The study of Native American sports offers valuable insights into indigenous cultures, history, and worldviews. These games provide a unique lens through which to understand:

- The importance of physical prowess and skill in Native American societies

- The integration of spirituality and daily life in indigenous cultures

- The complex social structures and gender roles within Native American communities

- The adaptability and innovation of indigenous peoples in creating games suited to their environments

As such, the preservation and study of these traditional sports serve not only cultural but also educational purposes, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of Native American history and heritage.

Challenges and Opportunities

Despite the rich legacy of Native American sports, challenges remain in preserving and promoting these traditions. Some of these challenges include:

- Loss of knowledge due to historical disruptions of Native American cultures

- Limited resources for organizing traditional sports events and programs

- Competition from modern sports and entertainment forms

- The need to adapt ancient games to contemporary safety standards and interests

However, these challenges also present opportunities for innovation and cultural revitalization. Many Native American communities are finding creative ways to blend traditional sports with modern practices, ensuring their relevance and appeal to younger generations while maintaining their cultural essence.

Future Prospects

The future of Native American sports looks promising, with increasing recognition of their cultural and historical value. Potential developments include:

- Integration of traditional games into physical education programs in schools

- Increased representation of Native American sports in mainstream media and sports coverage

- Development of cultural tourism centered around traditional Native American games and competitions

- Further academic research into the history and significance of these sports

As interest in cultural diversity and indigenous rights continues to grow globally, Native American sports stand poised to gain wider recognition and appreciation, both as historical artifacts and as living traditions that continue to evolve and inspire.

Native American Sports | Encyclopedia.com

Source

Popular Games. Despite the diversity of Native American cultures, some games were widespread. The rules of a game might vary, but several games were popular in large regions of the West. Native Americans occasionally incorporated games into religious ceremonies. Heavy betting was common with most games.

Lacrosse. The best known of Indian games is lacrosse. It was most common among the tribes of the Atlantic seaboard and around the Great Lakes, but it was also played in the South, on the plains, in California, and in the Pacific Northwest. It was played with a ball made either of wood or of buckskin, which was caught with curved rackets with a net on one end. The goal was usually marked with two poles although in some areas only one was used. In 1860 J. G. Kohl, a white traveler in Wisconsin, examined some lacrosse equipment. He admired the fine carving of crosses, circles, and stars on the white willow ball and praised lacrosse as “the finest and grandest” sport of the Indians. Although he was unable to see a game, he claimed that the Indians “often play village against village or tribe against tribe. Hundreds of players assemble, and the wares and goods offered as prizes often reach a value of a thousand dollars and more.”

Shinny. A kind of field hockey known as shinny was among the most popular Native American games. It was usually played by women, but sometimes, especially on the plains, might also be played by men. Among the Sauk, Foxes, and Assiniboine Indians, men and women played the game together, and among the Crows, teams of men played against teams of women. Native Americans in the East, on the plains, in the Southwest, and on the Pacific Coast played shinny. It was played with a ball or bag, often made of buckskin, which was hit with sticks curved at one end. The ball and sticks might be decorated with paint or beads. The length of the field varied from two hundred yards (among the Miwok Indians) to a mile or more (among the Navajos). The object of the game was to hit the ball through the opponent’s goal. The ball could be kicked or hit with the stick but not touched with the hands.

Snow-Snake. In regions of the West cold enough to have snow and ice in the winter, snow-snake was played. Its rules varied even more than those of lacrosse or shinny, but in general the game involved sliding darts or poles along snow or ice as far as possible. The projectile could be only a few inches long or might be a javelin up to ten feet long. The game was usually, but not always, played by men. Among the Crees, who played a variant of the game in which the dart had to pass through barriers of snow, only men played the game. Among the Arapahos, on the other hand, snow-snake might be played by adults or children but was most commonly played by girls.

Hoop and Pole. Hoop and pole was another widespread game with varying rules. In general a hoop was rolled along the ground while men tried to knock it over with spears or arrows. The hoop was usually relatively small, from three inches to a foot in diameter. The hoop might be open, but often the players stretched cords or a net across it. The hoop itself was often of wood but might be made of corn husks, stone, or iron. It was sometimes decorated with paint or beads. The score was determined by the way the hoop fell when hit by the pole. The game was most frequently played by two men although in some cases more participated.

Among the Apaches

In the 1860s Col. John C. Cremony described a Mescalero Apache game as follows:

There are some games to which women are never allowed access. Among these is one played with the poles and a hoop. The former are generally about 10 feet in length, smooth and gradually tapering like a lance. It is marked with divisions throughout its whole length, and these divisions are stained in different colors. The hoop is of wood, about 6 inches in diameter, and divided like the poles, of which each player has one. Only two persons can engage in this game at one time. A level place is selected, from which the grass is removed a foot in width, and for 25 or 30 feet in length, and the earth trodden down firmly and smoothly. One of the players rolls the hoop forward, and after it reaches a certain distance, both dart their poles after it, overtaking and throwing it down. The graduation of values is from the point of the pole toward the butt, which ranks highest, and the object is to make the hoop fall on the pole as near the butt as possible, at the same time noting the value of the part which touches the hoop. The two values are then added and placed to the credit of the player. The game usually runs up to a hundred, but the extent is arbitrary among the players. While it is going on no woman is permitted to approach within a hundred yards, and each person present is compelled to leave all his arms behind.

Source: Stewart Culin, Games of the North American Indians, volume 2, Games, of Skill, Twenty-fourth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1992), pp. 449–450.

Stewart Culin, Games of the North American Indians, volume 2, Games of Skill, Twenty-fourth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1992).

History of Native Americans in Sports

From lacrosse to the blanket toss, sports in Native tradition have evolved and endured. Whether the origin is survival or entertainment-based, sports have always played and continue to play an important role in Native American history. Canoeing, snowshoeing, tobogganing, relay races, tugs-of-war, ball games, and lacrosse, are just a few of the sports games early Native Americans played and still enjoy. The traditional game of lacrosse originated in the Iroquois Confederacy. Not only did lacrosse provide the means to challenge oneself physically (it was nicknamed “little brother of war”), it was also considered a gift from the Creator, played for various spiritual reasons, and used to heal the sick.

Perhaps the most famous American Indian athlete of all time is Jim Thorpe. In 1907, Thorpe persuaded legendary football coach Pop Warner to allow him to try out for the Carlisle “Indians” college football team. After starring for the team, he went onto stardom in numerous athletic endeavors including as an Olympic athlete and professional player in basketball, football, and baseball. The Carlisle Indian football team where Thorpe began his athletic career, had a winning percentage of 65% from 1893 until its final year in 1917, making it the most successful defunct major college football program of all time. Carlisle was a national football powerhouse regularly competing against other major programs including Ivy League schools. The Indians were consistently outsized by their competitors, and in turn, they relied on speed and guile to remain competitive. Carlisle’s playbook gave rise to many trick plays and other innovations such as the overhand spiral throw and fake handoff which are now commonplace in American football.

The Hominy Indians were an all-Indian professional American football team which played in the 1920s and 1930s. The team was based in Hominy, Oklahoma with players from 22 different tribes. They were named state champions in 1925, and in 1927 they defeated the NFL world champion New York Giants.

A more recent phenomenon in Indian country is the passionately followed Native American version of basketball called “reservation ball” or rez ball for short. Rez ball is a fast tempo, transition-based style of basketball that features quick shooting, and aggressive defense that looks to force turnovers through pressing and half-court traps. Many American Indians have gravitated to basketball as a means to get together and overcome strife often faced on reservations. Building upon the popularity of basketball in Indian Country, the Native American Basketball Invitational (NABI) was launched in 2003. The Arizona-based tournament has become the premier all-Native youth tournament in the world and was sanctioned by the National Collegiate Athletic Association(NCAA) in 2007.

Native American athletes and fans face ongoing racism (Hostile team spirit) — High Country News – Know the West

The U.S. has seen a rise in hate crimes, but data shows that bigotry is a constant in Indian Country.

Some of the students were crying as they got back on to the bus. In early 2015, Justin Poor Bear, now 39, chaperoned dozens of Native students to see a Rapid City Rush ice hockey game in South Dakota. The trip was part of an after-school program at American Horse School on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. “It’s not your fault,” Poor Bear told the bus full of kids as he drove home. During the third period, the chaperones alleged a white man poured beer on two of the students and called them racist slurs, a claim that could not be proven in court. Poor Bear was angry: He remembered experiencing the same kind of treatment during his high school basketball games in the ’90s.

“When you first hear the words, ‘Go back to the rez, prairie nigger,’ or name calling, it’s a shock moment,” said Poor Bear. “Then you realize they’re referring to us.” His basketball coach would tell the team: Don’t engage.

Rural towns are often highly supportive of their high school sports teams, and reservation athletics are no different. But racism has been rising in U.S. sports for the past four years, according to the Institute of Diversity and Ethics in Sport at the University of Central Florida, and Native American athletes and fans are often subjected to racist bullying at sport events. In fact, for Native Americans, this treatment has been the rule, not the exception, for many years.

A frequented basketball court in Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota. Though sports are at the center of Indigenous communities, teams often face targeted racial bullying from competitors.

Kalen Goodluck

From 2008 to 2018, there have been at least 52 reported incidents across the U.S. of racial harassment directed at Native American athletes, coaches and fans, according to data compiled from news articles, federal reports and court documents by High Country News. Reported incidents ranged from racist vandalism and tweets, to banners that read, “Hey Indians, get ready for a Trail of Tears Part 2,” a reference to the 19th century death march endured by tribal citizens who were illegally and forcibly relocated to Oklahoma by the U.S. government. Other instances include players being called names like “prairie nigger,” “wagon burners” and “dirty Indians.” Nearly all 52 reported incidents involved high school sports, but there were also four university game cases and even a fast food restaurant sign that read, “‘KC Chiefs’ Will Scalp the Redskins Feed Them Whiskey Send – 2 – Reservation.” Nineteen incidents occurred at basketball games; 20 incidents were at football games.

Of the 52 incidents, 26 resulted in remedial actions, including 15 apologies to the Native victims. At times, multiple responses were taken, including nine disciplinary actions — a team suspension, a few school investigations, an academic suspension, volunteer positions revoked at school, an athletic team meeting, a juvenile detention sentence and a disorderly conduct charge. But in the remaining 26 incidents, no remedial or disciplinary action was taken.

“In places we think of as ‘Indian Country,’ and especially adjacent border towns, Indigenous athletes do experience escalated rates of harassment,” said Barbara Perry, director of the Centre on Hate, Bias and Extremism at the University of Ontario Institute of Technology, who spent years studying hate crimes against Indigenous people in the U.S. and Canada. This harassment level may also extend, Perry said, to schools outside Indian Country with Native mascots. In a 2012 report to the Oregon State Board of Education, the state superintendent wrote that the use of Native American mascots “promotes discrimination, pupil harassment, and stereotyping” against Native American students in school and during sports events.

At a hearing in Fort Pierre, South Dakota, held by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights last year, Vice Chairman of the Crow Creek Sioux Tribe Barry Thompson testified on racism against Native American athletes. A former basketball coach himself, he recalled an episode that occurred when his team travelled to Miller, South Dakota, in 2002. Throughout the game, Thompson said, a handful of grandparents from the other team made derogatory comments to him and his players, including the epithet “prairie nigger.” After the game, while his team ate at a Dairy Queen, a group of boys rolled up in a car and began yelling at them. As the players left, the other boys fired a shotgun into the air over their heads.

Broadly speaking, professional athletes are more likely to experience racism in the forms of hiring opportunities than public overt acts of racism, according to Richard Lapchick, founder and director of the Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport. “This stands in stark contrast to Native Americans who are confronted with racist names and mascots in many sports across the country.”

Reported acts of racism in U.S. sports reached a high in 2018.

Source: Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sports

According to psychology studies, race-based mascots evoke associations with negative stereotypes, and establish unwelcoming and even hostile school environments for Native students. A 2008 study found that when Native youth were presented with Native American mascots, they were more likely to express lower self-esteem. Yet white youth “feel better about their own group” when presented with a Native mascot, said researcher Stephanie Fryberg, professor of psychology and American Indian studies at the University of Washington.

Reported acts of racism in U.S. sports have been increasing each year since 2015, according to the Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport. The institute counted 11 in 2015; 31 in 2016; 41 in 2017; and 52 racial incidents in U.S. sports in 2018. “The rise in hate crimes and hate incidences are up all across the country,” said Lapchick, the institute’s founder. Meanwhile, the number of hate groups in the U.S. has reached a historical high, while federal authorities reported a 17% increase in hate crimes between 2016 and 2017.

Though it’s clear that racial harassment happens in many sports, it’s difficult to know how frequently other racial groups are affected, mainly for lack of research. For example: Last fall, a number of black and Latino high school football players across the country reported seeing racist signs and hearing racial epithets. Numerous studies on race and athletics focus on subtle, systematic forms of racial discrimination in professional and collegiate sports, as seen in team demographics, media representation, and the opportunities and salaries that athletes receive, though mostly for black athletes. Several studies with small cohorts conveyed a range of anecdotal evidence that African Americans face significant racist treatment by coaches, media, fans and teammates.

An analysis of a 2013 statewide survey of Minnesota public, charter and tribal schools may give a possible glimpse into the scope of the problem for Native students. The study found that Native American students reported being bullied because of their race over three times as often as white students did. Hispanic, black and Asian students reported racist bullying nearly four times more often than white students did. While the rate at which each group is targeted by race in sports remains unknown, Barbara Perry said, “Indigenous communities likely are among the most vulnerable.”

Though national rates of bullying have remained relatively steady in recent years, in 2017, the Centers for Disease Control found that nearly 22% of Native Americans and Alaskan Natives were bullied on school property, higher than the national rate of 19%. Yet research into the effects of bullying against Native Americans and Alaskan Natives is “nearly non-existent,” according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, a government agency devoted to mental and behavioral health.

Not only is there a study gap in overt sports racism, but the data High Country News gathered also suggest that accountability is an issue: Half of the publicly reported racial incidents against Native Americans received no disciplinary or remediating action.

“Racism is everywhere, and it’s about nothing that you did wrong,” Justin Poor Bear told his son after the hockey game incident. “You move past it.” He was sad because Brendan was so young at the time, experiencing that kind of racism in sixth grade. Now an athlete like his dad, Brendan Poor Bear started running cross-country as a freshman in high school. “Racism needs to be talked about now, especially with Natives. Everybody, not just Natives.”

Examples of reported incidents against Natives at sporting events, from 2008-2018 |

| In October 2017, the day before Sturgis High School in South Dakota was about to compete against Pine Ridge High School, an Oglala Lakota tribal school, social media showed an unauthorized pep rally that ended with students smashing a windshield with sledgehammers and spraypainting “go back to the rez” on a car. |

| In January 2017, fans from Pryor said they were denied entry from a basketball game at Reed Point High School because they were Native American. They were supported by a complaint filed by the Montana ACLU, but the Montana Human Rights Bureau found “no reasonable cause” for discrimination by Reed Point High School. |

| In early December 2013, Native American onlookers spotted a Sonic Drive-in signage in Belton, Missouri that read: “ ‘KC Chiefs’ Will Scalp the Redsk*ns Feed Them Whisky Send – 2 – Reservation,” referring to the Kansas City’s professional football team. |

| In 2013, a Cherokee high school football player in North Carolina received racist messages from a Swain High School player after the his team lost 32-0. The messages included racial slurs for American Indians and African-Americans as well as sexually vulgar references to the Cherokee player’s older sister. |

| In August 2014, at an OSU Cowboys vs. Florida State Seminoles game, a fan held a sign that read “Hands Up, Don’t Spear,” a combination of the phrase used to protest police brutality in the murder of Mike Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and the “Fear the Spear” phrase used by Florida State University. Another sign that read “Send ‘Em Home. #Trail_of_Tears #GoPokes” sparked immediate backlash across social media. |

Kalen Goodluck is an investigative reporter and photographer covering the environment, business and tribal affairs.

Email High Country News at [email protected] or submit a letter to the editor.

Get our Indigenous Affairs newsletter ↓

Read more

More from South Dakota

|

Is It Offensive for Sports Teams and Their Fans to Use Native American Names, Imagery and Gestures?

The night was winding down at The Rieger, an upscale casual restaurant in Kansas City, and a couple of Denver Broncos fans in town for a game last month were standing at the bar, engaging in some friendly ribbing with supporters of the hometown Chiefs.

At some point, the Broncos fans walked through the dining room. That’s when a Chiefs fan responded with a gesture as synonymous with the team as its red jerseys: He sliced his hand through the air in a chopping motion while bellowing a rhythmic chant.

Slowly but surely, most of the 50 or so diners dropped their silverware, turned toward the rivals and joined in, chopping the air in unison and chanting in a rising chorus that filled the restaurant.

This city’s beloved football team has left an unmistakable imprint on the local culture, whether it be the tradition of wearing red on the Fridays before games or the custom of modifying the national anthem’s final line to “and the home of the Chiefs” before kickoff at Arrowhead Stadium.

But perhaps the most indelible symbol of Chiefs fandom is one that unifies believers and divides others: the tomahawk chop.

Now that the Chiefs are on one of the biggest stages in sports, contending in the Super Bowl for the first time in 50 years, there is new scrutiny on the tradition.

For many fans, the chop and its accompanying chant — a pantomimed tomahawk motion and made-up war cry, also employed by fans of the Atlanta Braves, the Florida State Seminoles and England’s Exeter Chiefs rugby team — are a way to show solidarity with their team and to intimidate the opposition. But to many Native Americans — locally and afar — and others, the act is a disrespectful gesture that perpetuates negative stereotypes of the nation’s first people and embarrasses a city that fancies itself a hub of culture and innovation in the Midwest.

“It doesn’t show K.C. pride,” said Howard Hanna, the chef and owner of The Rieger, describing his dismay as the impromptu chop unfolded in his restaurant. “It makes us look stupid.”

The Chiefs have largely escaped the hottest embers in the national debate over American Indian mascots and imagery in sports. Their name does not evoke a slur like the Washington Redskins, and their mascot is not a red-faced caricature like Chief Wahoo, the logo that the Cleveland Indians began phasing out two years ago.

The organization has worked with Native Americans over the past six years to reconsider and reform some of its traditions. That dialogue resulted in the team’s discouraging fans from dressing in Indian regalia and asking broadcasters to refrain from panning to those who disregard the request. The team makes informative announcements about Native American history and tradition during some games, and a group of Natives hands out literature at the stadium. The team sometimes invites Native people to bless the drums that are ceremonially beaten before games.

The Chiefs have shown little appetite, however, for preventing their supporters from doing the chop.

“The Arrowhead Chop is part of the game-day experience that is really important to our fans,” Mark Donovan, the team president, recently told The Kansas City Star.

The local Indian community’s views on the tomahawk chop run the gamut, Crouser said, from those who think it is fine to others who are offended.

“As an organization, part of our mission is to empower Indian people,” said Crouser, who is a member of the Standing Rock Sioux. “And things like the tomahawk chop don’t empower Indian people. It’s still very stereotypical and mocking of an entire race of people.”

A survey of Native Americans — conducted by researchers at the University of Michigan and the University of California, Berkeley, and set to publish next month — found that around half of respondents were bothered or offended when sports fans did the tomahawk chop or wore Indian headdresses. Opposition was even greater among those who frequently engaged in Native traditions, with 65 percent saying the chop bothered them, according to the report, which will appear in the academic journal “Social Psychological and Personality Science.”

Other research suggests that even when Natives see mascots or imagery as positive, they can still do psychological harm, damaging the self-esteem and ambitions of American Indian youth.

“There’s no way that the use of Natives as mascots is honoring,” said Stephanie Fryberg, a University of Michigan professor who is Tulalip and worked on the survey. “That’s an illusion.”

The tomahawk chop causes ambivalence among some Chiefs fans — they understand why Native people might find it offensive, but say they do it to celebrate their team, not to demean Indians. Several fans said they would have no problem giving up the chant and replacing it with something else, but that the team would have to lead that effort.

Joyce Parker, 65, cringed as she admitted that she does the chop at games.

“It’s just that caught-up-in-the-moment group joy,” said Parker, a fan from Prairie Village, Kan., a suburb that is a 10-minute drive southwest of Kansas City. “Yes, I feel bad about it.”

It’s the North American Indigenous Games! | Explore | Awesome Activities & Fun Facts

Canadian Press

From July 16-23, 2017, Toronto is hosting an amazing event! The North American Indigenous Games (or NAIG) are coming! There’s so much happening during the games, from sports to cultural events, so let’s start exploring.

Who is participating?

Participants gather to promote the 2017 North American Indigenous Games, held in Toronto from July 16-23. (Photo from NAIG Host Society)

The North American Indigenous Games have been around for over 25 years although there haven’t been 25 of them. Unlike the Olympics, the NAIG isn’t held regularly. Some games have been as little as two and as many as six years apart. For the first time, they’re being held somewhere other than the western provinces! The 10th NAIG is bringing together over 5,000 young athletes between the ages of 13 and 19 from all 13 provinces and territories, as well as 13 regions of the U.S., to celebrate the incredibly rich heritage of Canada’s Indigenous people.

What sports are there?

Mekwan Tulpin, a Cree from Fort Albany First Nation is helping coach Team Ontario in lacrosse. (CBC)

The athletes will compete in a variety of sports; some that were even invented by our First Nations people. There are 14 sports featured in the North American Indigenous Games including canoe and kayak races, lacrosse, rifle shooting, badminton, baseball, basketball, golf, soccer, softball, swimming, volleyball, wrestling and athletics (which includes track and field events and cross country races).

Warren Collins of Cochrane, Alberta, is only 15 years old, but he is already making a name for himself in competitive archery. (Photo provided by Jayena Collins)

A sport you may not have seen before is 3D archery. It’s different than regular archery because archers shoot at 3D targets shaped like animals that are placed at varying distances instead of shooting at round targets placed at the same distance. The athletes have to use their skills not only to figure out the distance of the targets, but also the scoring rings placed in different spots on each target.

Are there other events?

Kelly Duquette of the Métis Nation of Ontario, is a 22-year-old artist and student specializing in Indigenous law. (Photo from Kelly Duquette/CBC)

You won’t just see sporting events at the NAIG. The NAIG will also celebrate Indigenous culture and the heritage of the participants with an amazing showcase of music, food, art and entertainment. Between sports competitions, you can snack on traditional foods such as Indian tacos and bannock or you can also check out the arts and crafts of First Nations, Métis and Inuit artisans at the Indigenous Marketplace.

Karahkwiiohstha King, who also goes by Feryn, teaches and performs traditional Mohawk dance. (Photo from Karahkwiiohstha King/CBC)

You can also catch a drum circle or a dance performance by dancers and musicians from across North America — or Turtle Island, which is the Indigenous name for North America — at the Cultural Festival.

What does the logo mean?

Take a look at the 2017 NAIG logo. The simple design shows an eagle, a feather, a sash and the colours of the Aurora Borealis, or the northern lights. The design isn’t just pretty — these symbols of the First Nations (feather), Métis (sash) and Inuit (northern lights) represent all of the Indigenous people of Canada coming together, and the eagle is a symbol of the strength and wisdom of the people.

Recreation and Games | Milwaukee Public Museum

Among the Woodland Indian, games were played not merely for recreation, but also for significant religious reasons: To honor the spirits and to cure the sick.

There were both games of dexterity and games of chance, and betting was also customary. In addition, there were games for children. Later, modern cards and card games were adopted from Whites. Games were played by men, by women, and by the children, but only rarely did the two sexes, as adults, play together.

Wrestling and Kicking

Wrestling was popular with the men, as were foot-racing and bow-shooting, all done in a competitive spirit. Among the Menominee as well as the Ho-Chunk, a rough game called Ato’wi frequently started when a crowd was gathered, and usually deteriorated into a free-for-all fight. Someone shouted “Ato’wi” in a loud voice, and immediately the men began kicking each other on the buttocks as hard as they could, all the while shouting Ato’wi. The object was to see who could keep their temper best and for the longest time.

Moccasin Game

The moccasin game was played by men, and wagers were invariably placed by those watching the game. Four men (some tribes used five, others eight) sat on opposite sides of a blanket. Nearby was a drummer (for the Menominee) or a drummer for each player (among the Ojibwe). There were special songs for the moccasin game, and the drummer sang and played a tambourine drum. The equipment consisted of four tokens, one of which was marked, four moccasins or small pieces of decorated cloth, and sticks for counters. The object was to hide the tokens under the moccasins, in full sight of the opponents, who then had to guess which moccasin concealed the marked token. There were many pretenses of hiding and removing them, so that one’s opponent found it difficult to accurately guess where the marked token was hidden. Four attempts were allowed, and then the next player had a turn. The Potawatomi used just one token with four moccasins. The Ojibwe, Ho-Chunk, and Menominee used a “striking stick” to turn over the moccasin thought to hide the token. When neighboring tribes visited each other, the players were usually chosen from opposing tribes. Early White settlers, who also enjoyed gambling, adopted the game so zealously that in Indiana, a statute expressly forbade gambling at the moccasin game and other gambling games and stiff fines were set.

The Hand Game

The hand game was another guessing game, which consisted of hiding two small objects in the hands of the players. The opponent was to guess the correct hands in which the objects were hidden, for any number could play. Fairly small articles were used: a horseshoe nail wound with string or a pebble sewn into a piece of cloth. Sharpened sticks were thrust into the ground to keep score.

Double Ball

The double ball game, played only by the women, somewhat resembled lacrosse. The double ball was composed of two small, oblong deerskin bags joined together by an eight-inch deerskin thong. The Potawatomi played with five on a side, each woman equipped with a straight stick three or four feet long. The Ojibwe, however, had many more players on a side, and each one used a pair of sticks with slight curves at the striking ends. The object was to hit the opponent’s goal, the goal posts being about 300 feet from each other. As in lacrosse, the goalies endeavored to protect their own goal. The double ball was thrown into the center of the field, and points were scored when a player finally hit the opposing goal with her two sticks (or stick) or with the double ball. This game was for sturdy women who could run swiftly. Individual’s sticks had identifying marks of paint and colored ribbons. Among the Potawatomi women, it was played much like lacrosse, with sponsors who called and started the game and furnished prizes but did not play themselves. The men spectators yelled and whooped when a goal was scored, and the woman winning a prize would give it to a spectator (very possibly her cross-uncle), who was obliged to return a gift of equal value at a later time.

Dice

The dice game was played mostly by women in winter, in place of double ball. The game was sponsored by a woman to honor her guardian spirit, and the ceremonial preliminaries were similar to those of double ball and lacrosse.

Among the Potawatomi, after a feast, a blanket was spread out on the floor, and the women divided into two teams and sat facing each other, each side in a semicircle. Any number of women could play, but there were only four prizes, usually lengths of cloth in various colors. The gaming equipment consisted of a wooden bowl and eight dice. Six of the dice were thin circular disks; one was carved in the form of a turtle, and one represented a horse’s head. They were formerly made of buffalo rib, but horse ribs were common in later times. One surface of each die was colored blue or sometimes red, and the other was left white. The bowl was held with both hands and the dice were shaken to the far side of the bowl. Then the bowl was given one flip and set on the floor and the score was counted, as follows:

All of similar color except 2: 1 point

All of similar color except 1: 3 points

All of similar color except turtle: 5 points

All of similar color except horse: 10 points

All of similar color: 8 points

All of similar color except turtle and horse: 10 points

The scoring varied according to each tribe, and each woman kept her own score using beans in front of her. Each woman shook until she missed twice and then passed the bowl in clockwise rotation. The first to score ten points won the game, and her prize-a piece of yard goods-was given to one of the men spectators, who in turn was obliged to reciprocate with a gift of equal value in the future.

Cup and Pin

The cup and pin game is one of the oldest and most widespread games in North America and had several names: bone game; cup and pin; and ring and pin. It was played by both men and women. Ten deer dewclaws or deer toe bones were strung on a narrow piece of deer hide. At one end was an oval piece of leather with small holes, 25 in some cases, and at the other end was a long needle of bone or wood. During later times, a brass thimble replaced the bone next to the leather, and a darning needle was substituted for the bone needle.

The rules varied, but among the Ojibwe, many people could play and were divided into two teams. Together, they decided how many points would make a game and how many points would be given for the most difficult play, which was catching the bone or thimble closest to the pin. Each player continued as long as he continued to score, passing the cup and pin to his opponents when he failed. To play, each person held the needle and swung the string of bones forward to catch one or more of the bones on the needle, the object being to hold a number of bones on the needle. Each bone counted as one point, and if all the bones were caught, that player scored ten points. To catch the piece of leather scored as many points as there were holes in the leather. As players scored points, the total score was shouted by all the players. The total number of games won was indicated by sticks placed upright in the ground.

Snow Snake

Snow snake was played in winter by men and boys on the frozen lakes or in long grooves made in the snow. The snow snake was a hardwood stick two to six feet long and a half to three-quarters inch thick. The stick had a slightly bulbous end that resembled the head of a snake, with eyes traced on it and a crosscut to mark the mouth. The entire stick was carefully smoothed. With his forefinger, a man would hold the tapered end lightly, his thumb on one side, while he balanced it with his other hand. He took a short run, then bent and flipped the snake so it would race along the top of the ice or snow. Wagers were made on whose snake could travel the farthest. Snow snake is no longer played by the Indians of the western Great Lakes, but is still popular among the Iroquois. Their snakes were longer — from four to eight feet — and are also polished, waxed, and weighted with lead at the head end to gain distance. The Iroquois prepared a snow ramp, which gave additional speed at the release. By dragging a log through the snow, they pressed down a track that was sometimes a mile long.

Children’s Games

In addition to the girls’ dolls and the boys’ bows and arrows, the children learned all the games mentioned at an early age. In addition, they had a few of their own games. They played a game similar to cup and pin which required less dexterity, using a pointed stick and a bunch of grass tied to an end of a short string or cord. Another simple game was the hoop game, which was simply a birchbark hoop which the children rolled around. Mothers would encourage their youngsters to roll these hoops just before dark so they would tire and sleep well. Another game consisted of a small ring fashioned from a leg bone of an animal, and a sharp metal point set in a wooden handle. The ring was set on the ground and the awl that was thrown toward it, the purpose being to stand the awl upright inside the ring.

Nowadays, various types of games and competitions related to physical and intellectual activity are called in one word – sport. And if you are asked what you know about Indian sports, then cricket is the first thing that comes to mind. However, India is a great country with a unique history and culture that has given birth and development to numerous types of competitions and sports games.In the great epics “Ramayana” and “Mahabharata” one can find many references to the popularity of various types of martial arts and competitions among the military class. In these epics, the beauty of the body of athletic, physically strong men is glorified. Even during archaeological excavations at Mohenjo Daro and Harappa, swords, spears and pikes were found, confirming that physical fitness was an important part of the life of the people of that time. During the reign of the Great Mughals, archery and various types of wrestling flourished.During the reign of Emperor Shah Jahan, the Red Fort became the main arena of wrestling tournaments. In the Middle Ages in Central India, the rulers of Marathi, to popularize physical culture among the younger generation, built many temples dedicated to Hanuman, personifying strength and courage. Indian martial arts (single combats) The martial arts of India are represented in a huge variety of forms and styles. Each region of the country practices its own style. All systems of Indian martial arts are grouped under various terms derived from either Sanskrit or Dravidian languages.One of the most common terms is Shastra Vidya (Sanskrit) , or the Science of Weapons. In the Puranic literature, the Sanskrit term Dhanur Veda (dhanushya – “bow”, Veda – knowledge) is used for all martial arts in general, which literally translates as “Science of archery”. There are many references and detailed descriptions of martial arts in the literary monuments of India. Like other aspects of Indian culture, martial arts are conventionally classified into Northern and South Indian styles.The main difference is that the northern styles were influenced by Persian influences, while the southern ones retained ancient conservative traditions. All of these, both northern and southern styles of Indian martial art, developed in different eras and most often in response to socio-political situations. Bodhidharma Bodhidharma is considered the main figure in the spread of traditional martial art of India throughout Southeast Asia (V-VI centuries BC).), “The third son of the great king of the Pallav dynasty.” Leaving secular life, he went to China in order to carry the true meaning of Buddhism. Staying at the famous Shaolin monastery, Bodhidharma, along with the Mahayana teachings, passed on to his disciples the martial techniques that allow him to keep his body in excellent physical shape. It is he who, without exaggeration, is the progenitor of all types of martial arts that have arisen: from Wushu in China, Thai boxing in Thailand, Korean Taekwondo, Vietnamese Viet Vo Dao, to Japanese Jiu-Jitsu, Karate and Aikido. Wrestling and hand-to-hand combat Wrestling has been popular in India since ancient times and is known here under the general name malla-yuddha .Some forms malla-yuddhi were practiced on the territory of the Indian subcontinent even in the pre-Aryan period. The famous Indian epics describe the stories of great heroes, fanned with glory, wielding various types of wrestling. One of the main characters of the “Mahabharata” Bhima was a great fighter. Jarasandha and Duryodhana were praised along with Bhima. The Ramayana colorfully describes Hanuman as an excellent wrestler. During British rule, wrestling becomes part of the military training of soldiers who served in the British army in India. Nowadays, Malla Yuddha has practically disappeared from the northern states of the country, surviving only in the form of kushti .Traditional fights malla-yudhi can be seen today in Karnataka and remote areas of Tamil Nadu, where training begins at the age of 9-12. Malla-yuddha Pehlwani / Kushti Technique kushti is based on the techniques of malla-yuddhi and also uses four styles: bhimaseni, hanumanti, jambuvani and jarasandhi.Wrestlers kushti are called pahalwans / pehlwans, while mentors are ustad . During training, the pakhalwans perform hundreds of squats, as well as push-ups with a wave-like torso movement, both on both legs and on one. Various training shells are also used, such as Karela, Gada and Ekka – heavy wooden or stone clubs; nal – stone weight with a handle in the center, garnal – stone ring worn around the neck.Also, rope climbing and running are an integral part of the physical training of wrestlers. Complementing the workouts with massage and a special diet that includes sattvic products: milk, ghee (ghee) and almonds, as well as sprouted chickpeas and various fruits, pakhalvans achieve speed, agility, agility with a significant weight. Fights are held in round or square arenas, usually dug in the ground, called akhada .The winner is awarded the title Rustam , in honor of Rustam, the hero of the Persian epic Shahnameh. The most outstanding of the great kushti wrestlers was Gama Pahlavan, or Great Gama, who in 1910 received the title Rustam-e-Hind, champion of all India. Duel of Great Gama Great Gama Vajra Mushti History Vajra Mushti and its further development is lost in the depths of antiquity. It is only known that Bodhidharma, being a master of this type of Indian martial art and guru varma-kalai, about which will be described below, brought it to China. (About Bodhidharma see here) From vajra-mushti all existing famous Asian martial techniques developed.This martial art is eloquently described in the Buddharata Sutra, dating from the 5th century. AD, as well as in “Manasollas”, written by Someshvara III (1127-1138), king of the western Chalukyas. The Portuguese traveler and chronicler Fernan Nunez, who lived for three years (1535-1537) in the capital of the Vijayanagar Empire, described countless fighters vajra-mushti who entered the ring for the pleasure of the king. Vajra Mushti , like its unarmed counterpart Malla-yuddha, was fiercely practiced by the clan of Gujarati fighters Jyestimalla (lit.The greatest warriors), which are described in detail in the “Malla Purana” dating from the 13th century. It is believed that the Jyeshtimalla, in contrast to the Kerala Nair (a group of Kshatriya (warrior) castes), belonged to the Brahman caste. Since the 18th century. Jyeshtimallahs were under the patronage of the Gaekwad dynasty (a Maratha clan that received the right to collect taxes from all over Gujarat). During the colonial period, Jyeshthimall became known simply as Jetti. After India gained independence, the descendants of the Joshimallah clan live in Gujarat, Rajasthan, Hyderabad and Mysore.Without royal patronage, the Vajra Mushti traditions have lost their prestige. Modern Indian people consider this martial art to be cruel and medieval. But still, the battles are held during the Dushehra festival and, unlike the competitions of the past, are not so bloody. In the old days, the fight vajra-mushti often ended in the death of one of the participants. Today’s fighters use blunt knuckle dusters or wrap ocher-dyed cloth around their fingers to mark hits on the opponent’s body.In addition, the fight ends immediately after the first blood is shed. Mushti-yuddha Mukna Styles combining weapons, riding, fighting and hand-to-hand combat Kalari Payattu and Varma Kalai (Adi Murai) Kalari-payattu are mistakenly divided into two styles – northern ( wadakkan Kalari ) and southern ( adi murai or varma-kalai ), although these are completely different types of martial arts in their origin and technique. Varma-kalai (Adi murai) – a martial art that originated in the II century. AD in Tamil Nadu, where it is still widely practiced. Varma-kalai consists of three components: adi-murai (martial art), vaasi yoga (breathing exercises) and varma vaidhyam (healing injuries and curing diseases). The basis for varma-kalai was the healing art known as varma chuttiram , which is based on the study of vital points on the human body. Varma-kalai is characterized by short, straight and powerful lines of attack. The main emphasis here is aimed at hitting vital points (varma / marma) with both hands and weapons (stick). Varma-kalai is intended for self-defense, and the main emphasis is on stopping the attacker, and not inflicting numerous injuries on him. Particular attention is paid to sparring – a training fight in which you can hone the acquired skills.Unlike kalari-payatu , the technique of hand-to-hand combat is first studied, and then they begin to use weapons, starting with wooden sticks ( silambam ), gradually passing to melee weapons. The training takes place in open spaces in any terrain, where you can easily work out a variety of combat scenarios. Teachers and masters varma-kalai are called asaan . In the treatment of injuries, knowledge is used that is not based on Ayurveda, but on the “Siddha”, the traditional Dravidian medical system.According to legend, varma-kalai , as well as Siddha ( siddha vaidyam ), were passed on to people by the famous saptarishi (sage) Agastya. Varma-kalai is one of the oldest combat systems in the world, which, as many scholars believe, was brought by Bodhidharma to China, where it became the basis for the creation of Wushu. Silambam (silambatam) Competitions for silambam are held on a round field. Participants compete in pairs or teams of two or three. Before the performance, they express their respect to God, their teacher, their opponent and all spectators. Victory is awarded to the one who manages to touch the opponent more times with his stick or knocks the stick out of his hands.In order to make it easier to count the number of blows, the ends of the sticks are covered with a sticky substance that is imprinted on the opponent’s body. Masters silambam , called asaan , can fight with sticks of various lengths, either one or two. They are able to acrobatically dodge attacks and attack in a high jump. Gatka – Sikh Martial Art Mardani Khel is a traditional Indian martial art originally from Maharashtra.In the XVII century. it developed into a single system of fighting techniques that the Maratha warriors possessed. The great Shivaji, who raised a rebellion against the Muslim rulers in the west of the Deccan, mastered this martial art as a child. During the colonial period, the Marathi regiment of light infantry was formed in Bombay to protect the possessions of the British East India Company, which perfectly owned 90,016 Mardani-khel. Statue of Bajdi Prabhu, commander of the Shivaji army Sky is a martial art that originated and is practiced on the territory of Kashmir both in India and Pakistan.Only legends tell about the origin of this martial art. But in all likelihood, it developed from protective techniques against wild animals. The first written mentions of skye date back to the reign of the Great Mughals. At this time, training skye became mandatory in the Kashmiri army, where this martial art was known as shamsherizen . During the era of British colonization of India, skye was banned. But after India gained independence, and after that the division of the country and the ongoing series of Kashmir border conflicts, about sky was completely forgotten.Only in 1980 Nazir Ahmed Mir, master of skye, revived this martial art, adding elements of karate and taekwondo. The creation of the Indian Sky Federation later allowed this type of martial art to be brought to the national level. Huen Langlon – the martial art of Manipur. The history of its origin is rooted in ancient local legends about the gods. But still, if we adhere to scientific and historical versions, then this martial art arose in the continuous struggle for life between the seven dominant clans of Manipur.In the Manipuri (or Meitei) language, huyen means “war” and langlon means “knowledge.” Mallakhamba is a unique traditional Indian acrobatic gymnastics.It is known that the technique mallakhamba was practiced already in the Middle Ages in the territory of Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh. The term mala means “fighter”, and khamba means “pillar”, i.e. wrestling post. Initially, such pillars were used by wrestlers as training facilities for gymnastics. Later, this term was assigned to technology. Today, athletes in this discipline practice exercises on a pole, hanging poles and ropes. Gymnasts demonstrate mesmerizing aerial yoga poses, complex acrobatic figures or enact a wrestling scenario – all in the air. Mallakhamba strengthens muscles, makes the body flexible and agile, but requires a lot of dedication and endurance. For more than 20 years, India has hosted national tournaments of mallakhambu , where both men and women and adolescents take part. The pole exercises are performed mainly by men and boys, while the rope exercises are performed by women and girls. National Sports Games Traditional games have always been an integral part of the great Indian culture.Throughout history, they have not lost their originality and retained their special lively character. Even the modern innovations introduced did not prevent it from retaining its special character. And if you look closely at this huge variety of traditional Indian games, you can see that they are very similar to each other and differ only in names and a slight difference in the rules of the game. Kabaddi (kabadi, kabadi) – the oldest team game that originated in Vedic times, which is at least four thousand years old.It includes elements of wrestling and tagging. Americans and Europeans mistakenly consider cricket to be the main Indian sport, but this place of honor in the life of an Indian has belonged to Kabaddi for centuries. According to the rules of the game, two teams, each with 12 players (7 players on the field and 5 players in the reserve), occupy two opposite sides of the playing field measuring 12.5 mx 10 m, separated in the middle by a line. The game begins with the fact that one team sends an “invader” to the dividing line, who at the right moment runs across to the territory of the other team (the other half of the field).While he is there, he continuously shouts, “Kabaddi! Kabaddi! ” But on the territory of the enemy, he can stay only as long as he can scream, without catching his breath. His task, while he is shouting, is to touch the opponent’s player (one or more) with his hand or foot and run away to his territory (part of the field). If he needs to catch his breath, he must run, since the opposing team, on the court of which he is located, has the right to grab him. His task is to run across the dividing line (return to his own part of the field) or, resisting, move an arm or a leg beyond the line.The opposing team must force him to do one of two things: either touch the ground, or take a breath (catch his breath). After the attacker successfully returns, the touched player of the other team is eliminated from the game. If the attacker is captured, then one of the members of the defending team becomes the attacker. The game continues until one of the teams loses all of its members. For the eliminated opposing player, each team earns points. The match lasts 40 minutes with a five-minute break between halves. Kabaddi received the status of a national game in 1918, and it entered the international level in 1936 during the Summer Olympic Games in Berlin. In 1950, the All India Kabaddi Federation was created, which regularly holds national championships. After her, the Federation of Kabaddi Lovers appears, uniting many active and capable young people under its roof. In 1980, the first Asian Kabaddi Championship was held.In 2004, the first Kabaddi World Championship took place, in which India won the first World Cup. Polo / sagol kangjei – the old game, which we now know as polo, originated in ancient times in Percy and was called chovgan . Spreading throughout the east as far as China and Japan, the game was very popular among the aristocratic class. However, the birthplace of the modern version of this game is considered to be Manipur, where it was known as sagol kangjei, kanjay bazi or pool . Manipur ponies are used to play Sagol Kangjei . This active and hardy horse breed is believed by some experts to have been bred by crossing a Tibetan pony with a Mongolian wild horse and an Arabian horse. Each team sagol kangjei has seven players, which symbolizes the seven ancient clans of Manipur.Having gathered together in the middle of the field, the teams are waiting for the referee to throw the ball up, from that moment the game begins. Players, armed with a reed stick, on horses rushing at full speed, try to throw a ball made of bamboo root into the end of the opponent’s field. There is no goal in manipur polo and a goal is scored when the ball reaches the edge of the opponent’s zone. Then the teams are swapped. Over time, the British established their own polo rules and reduced the number of players on the team to four.Today, equestrian polo is a traditional game that has entered the international arena with great success, as evidenced by the periodic international tournaments. The main polo season is from September to March. At this time, tournaments are usually held in Delhi, Calcutta or Mumbai. There is another kind of polo. This is camel polo played just for fun at the annual fairs in Rajasthan. Yubi Lakpi is a traditional football game like rugby played in Manipur.In the manipuri language , yubi means “coconut” and lakpi means “to grab.” Previously, it was held on the territory of the Bijoy Govinda temple during the spring Yaosang festival, where each team was associated with gods and demons. The tradition still exists today. Nowadays, the game is spread all over Manipur. At the beginning of the game, the coconut, pre-soaked in oil, is placed in front of the guest of honor (formerly the King of Manipur himself) or the judge.The referee, called the main and , starts the game and stops it for violations by the players. He sits behind the goal line. Players are prohibited from pressing the coconut to their chest, they can only hold it in their hands or under the arm. In yubi lakpi it is allowed to kick or punch opponents, as well as grab players who do not have a coconut in their hands. The game begins when a coconut is thrown from one side of the field to players trying to catch it. The team whose players each time carry the coconut over the goal line (the area inside the field, the center of the goal line that forms one of its sides) becomes the winner.To score a goal, a player must enter the goal area from the front, not the sides, and then he must cross the goal line while carrying a coconut. If none of the players succeeds in reaching the goal line with the coconut, all players line up and race to determine the winning team. Kho-kho According to the rules of the game, each team consists of 12 players (9 field and 3 substitutes). The match consists of two periods, which in turn are divided into pursuit races lasting 7 minutes, after which a 5 minute break is allowed. Eight players from the pursuing team squat in marked squares along the center line, each facing the opposite direction. The ninth player on the team waits at one of the posts and prepares to start the pursuit.Three players of the fleeing team are on the playing court, others are waiting at the sideline of the field. These players are free to move around the field, running between the seated players of the opposing team. An active player of the pursuing team can only move along that part of the field on which he stepped. To go to the other half of the field, he should run to the post and go around it. As soon as the pursuer catches up with the evader, the latter is out of the game. The pursuer has the right to transfer his place to any player from his team by touching him with his right hand and loudly shouting “Kho!”The seated one immediately jumps up and rushes in pursuit, but only along that part of the field into which he was looking. And the first to sit in his place. As soon as the first three is caught in its place, the other immediately runs out. So, until 7 minutes are up. Then the teams are swapped. A fleeing player can also be eliminated from the game if he touches the seated pursuers twice, and also fails to enter the field in time when his teammates were caught. For each player caught, the pursuing team receives one point.The game lasts no more than 37 minutes. Thoda is a traditional archer game that originated in the Kulu Valley, Himachal Pradesh. The name of the game comes from a round piece of wood called a thota, which is attached to the end of an arrow so that it does not injure the participants during the game. Local artisans specially make wooden bows from 1.5 to 2 meters long for this event, as well as arrows in a set. Thoda takes place every spring on April 13th or 14th for the festival of Baisakhi. Race Flounder / Flounder – Annual buffalo races, widespread in the coastal regions of Karnataka.This type of sports entertainment originated in the agricultural community of Karnataka since time immemorial. The annual tournament takes place before the start of the harvest in the period from November to March and symbolizes a kind of worship of the gods, the protectors of crops. Treadmills are set up in a rice field and filled with water so that it mixes with the soil and turns into mud. Competitions are held between two pairs of buffaloes, chased by farmers. Numerous teams follow one after the other. The festival attracts many buffalo racing fans.Spectators place bets. The winning pair of buffaloes will receive a delicious fruit treat, and the owner will receive a cash prize. Wallam Kali is a traditional canoe race held in Kerala. Translated from the Malayalam language Wallam Kali literally means “boat racing”. The competition takes place during the annual Onam festival and attracts thousands of people from all over India. Races are held on traditional Kerala boats.Competitions are held at a distance of 40 km. But the most spectacular are the so-called “snake boat” races, or chundan wallam, which are one of the symbols of Kerala culture. As the story goes, in the XIII century. during the war between the states of Kayamkulam and Chembakaseri, the ruler of the latter ordered the construction of a military ship. This is how the magnificent chundan valam was constructed, which serves as a valiant example of medieval naval shipbuilding.The length of the boat can vary from 30 to 42 meters, and its rear part rises 6 meters above the river, so that it seems as if a giant cobra with an open hood is floating on the water. Author of the article: V. A. Samodum (Bhudev) |

Olympiad of the Peoples of the North

The 49th World Eskimo-Indian Olympiad (WEIO), which was attended by athletes from the USA and Canada, has ended. Unlike the traditional Olympic Games, its participants competed in disciplines traditional for the peoples of the North, little or not known to the general public.

It is curious that the symbol of the WEIO Olympiad is six intertwined rings, but they symbolize not six continents, but six main ethnic groups of the indigenous population of Alaska: Aleuts, Eskimos and Indian tribes – Tlingits, Athapaskans, Haida and Simpsians.

All of these sports are based on actual Native American activities and fun. At the same time, for each of them there are detailed rules and records are registered.

For example, an athlete must carry four people (one hanging from the front, one from the back, two from the sides) to the maximum distance.This competition simulates the delivery of the meat of the killed animal to the camp.

Several types of competitions are held with one object – a soft and dense leather ball, the size of three fists of an adult man, suspended from a rope.

In the first case, the athlete jumps from a place and tries to get the ball with two clenched legs. In the second (“Canadian jump”), the jump is made from the spot – the task is to hit the ball with one foot (a similar technique is used by footballers when carrying out strikes with “scissors”).In the third (“Alaskan jump”), the athlete lies down under the ball and throws his body vertically up, leaning on one hand – he must also kick the ball. In all cases, the winner is the one who gets the ball suspended at the farthest distance from the floor. These exercises are believed to help develop the skills required for ambush hunting.

Some sports are designed to test a person’s ability to tolerate pain. These include “ear-pulling the rope”: two opponents sit facing each other – their ears are tied with a thin rope crosswise.At the command of the referee, the athletes – using exclusively the muscles of the neck and back – begin to pull the rope in their direction. The one who surrendered or bowed his head, yielding to the pressure, lost. It is explained that this sport teaches men to tolerate pain in their frostbitten ears.

Tight Jumping was originally used to locate prey in an area free from hills and trees. Nowadays, the competition takes place as follows: several people pull on several animal skins sewn together and toss the athlete as if on a trampoline.The winner is the athlete who can be in an upright position for the longest time.

Chief Judge of the Olympiad Robert Aikel says that the games are growing in popularity, with over 230 athletes taking part this year. According to him, in most cases athletes prepare for games on their own, there are no professional trainers yet, but every nation has developed a self-training system. Eikel expressed the hope that sooner or later the traditional Nordic sports will gain more prominence in the world, as “they teach people to show patience, courage, strength and dexterity.These qualities are necessary for everyone in life. ”

Compared to the multibillion-dollar costs of “regular” Olympiads, WEIO costs the organizers a paltry sum. Perry Ahsoegak, chairman of the board of directors of games, says that in 2010 the budget was $ 145 thousand. However, only about a third comes from sponsors – the rest of the funds the organizing committee earns on its own, sometimes in very exotic ways.

In addition to sports competitions, the program of the World Eskimo-Indian Olympiad also includes a competition of traditional dance groups (dances are accompanied by choral singing and playing tambourines) and a beauty contest.Almost everyone takes part in the competition – belonging to one or another indigenous people is not a prerequisite.

According to Ahsoegak, games are traditionally very popular with viewers: this year they were visited by about 4-5 thousand people every day (for comparison, the population of Fairbanks, where the competition was held, is approximately 35 thousand.

According to the US Census Bureau (US Census Bureau) for 2000 (the results of the last census that took place this year have not yet been published), about 97 thousand Alaska indigenous inhabitants live in the United States – 47 thousand Eskimos, 15 thousand Tlingits, Simpshians and Haida (these tribes lead a similar lifestyle , Tlingits and Haida are related to each other), about 15 thousand Athabaskans and 12 thousand Aleuts.Most of them (85-90% depending on the people) consider English as their native language – the exception is the Eskimos, among whom 52% have completely switched to English.

Read more reports about Alaska here

On what principle the IOC gives the green light to sports – Rossiyskaya Gazeta

Boxing may be excluded from the competition program of the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo, Japan. This fear arises from the latest decision of the International Olympic Committee, adopted at a meeting of the organization’s executive committee.

Gloves dropped

The IOC has temporarily suspended all plans to organize a boxing tournament in Japan. The sale of tickets, the development of a qualification and selection system for the Games, and so on are frozen.

The IOC and personally the head of the international Olympic movement Thomas Bach have long had complaints against the leaders of world boxing. The most worried about various judicial scandals and financial fraud of officials. The IOC is categorically not satisfied with the figure of the new head of the International Boxing Association (AIBA) from Uzbekistan, Gafur Rakhimov, who was elected in November – he is suspected of having links with the criminal world.

Boxing has been included in the Olympics program since 1904 (there was a break only in 1912), at the last Games in Rio de Janeiro, competitions were held in ten weight categories for men and three for women. The loss of this sport can be a painful blow for a huge number of fighters from all over the world and many fans.

The IOC has no questions to boxers, claims are addressed to the management of the sport. Photo: RIA Novosti www.ria.ru

The wrestlers caught on in time