How do public schools shape the identity of young Black males. What role do educators’ perceptions play in the academic experiences of African American boys. Can the educational system address the disproportionate disciplinary actions against Black male students. How do labeling and stereotyping affect the self-perception of young Black boys in schools. What strategies can be implemented to create a more equitable learning environment for African American male students.

The Disproportionate Disciplinary Actions Against Black Males in Schools

Statistics reveal a troubling trend in the American education system: Black male students are disproportionately subjected to disciplinary actions and suspensions. This phenomenon has persisted for decades, raising serious concerns about equity and fairness in our schools. Ann Arnett Ferguson’s groundbreaking book, “Bad Boys: Public Schools in the Making of Black Masculinity,” delves deep into this issue, offering invaluable insights based on three years of intensive research at an elementary school.

Ferguson’s study paints a vivid picture of the daily interactions between teachers and students, shedding light on the complex dynamics that contribute to this persistent problem. By focusing on a group of eleven- and twelve-year-old African American boys, the author provides a unique perspective on how these young individuals navigate a system that often seems stacked against them.

The Alarming Statistics

- Black male students are suspended at rates significantly higher than their peers

- Disciplinary actions against Black boys often begin as early as elementary school

- The pattern of disproportionate punishment continues through high school and beyond

Why do these disparities exist? Ferguson’s research suggests that deeply ingrained biases and stereotypes play a significant role in shaping educators’ perceptions and decisions. These preconceived notions can lead to a self-fulfilling prophecy, where Black male students are expected to misbehave and are therefore more closely scrutinized and harshly punished.

The Power of Labels: How Educators Shape Student Identities

One of the most striking aspects of Ferguson’s work is her exploration of how certain Black male students are identified by school personnel as “bound for jail.” This labeling process has profound implications for the students’ sense of self and their academic trajectories. Ferguson poses challenging questions: How does it feel for a young boy to be labeled “unsalvageable” by his teacher? What impact does it have on a child’s psyche to hear that a jail cell has his name on it?

Through extensive interviews and observations, Ferguson uncovers the complex ways in which these young boys respond to such labels. Contrary to the assumption that they might simply internalize these negative perceptions, many of the students in her study demonstrated a critical awareness of the labeling process. They actively questioned and evaluated the motivations behind these labels, showing a level of insight and resilience that challenges prevailing narratives about Black male youth.

The Psychological Impact of Negative Labeling

- Decreased self-esteem and confidence

- Increased likelihood of disengagement from school

- Development of oppositional behaviors as a coping mechanism

- Internalization of negative stereotypes about Black masculinity

- Potential long-term effects on academic and career aspirations

Can educators become more aware of their own biases and the power of their words? By recognizing the profound impact of labeling, teachers and administrators can take steps to create a more supportive and equitable learning environment for all students, particularly those from marginalized communities.

Exploring the Concept of “Getting into Trouble” from the Boys’ Perspective

Ferguson’s research goes beyond simply documenting the disciplinary disparities; it seeks to understand what “getting into trouble” means from the perspective of the boys themselves. Through interviews and participant observation in various settings – classrooms, playgrounds, movie theaters, and video arcades – the author paints a nuanced picture of how these young males navigate the school environment and construct their identities in the face of adversity.

This approach reveals that the boys’ behaviors and responses to disciplinary actions are far more complex than they might appear on the surface. Rather than accepting the labels placed upon them, many of the students engage in a process of critical evaluation, questioning the fairness and motivations behind the punishments they receive.

Common Themes in Boys’ Perspectives on Discipline

- Feeling unfairly targeted or singled out

- Perceiving a disconnect between their intentions and how their actions are interpreted

- Developing strategies to navigate or subvert the disciplinary system

- Seeking alternative sources of validation and respect

- Struggling to reconcile school expectations with community norms

How can schools bridge the gap between their disciplinary practices and the lived experiences of Black male students? By listening to and valuing the perspectives of these young boys, educators can gain valuable insights into creating more effective and equitable approaches to classroom management and student support.

The Role of Educators’ Beliefs in Shaping Student Outcomes

Ferguson’s research reveals a disturbing pattern in how educators’ beliefs about Black children, particularly Black males, shape their interactions and decisions. The author argues that many teachers and administrators operate under the assumption of a “natural difference” in Black children and a “criminal inclination” in Black males. These beliefs, often unconscious or unexamined, can have profound consequences for how Black male students are treated within the educational system.

By supplementing the perspectives of the boys with interviews from teachers, principals, truant officers, and relatives, Ferguson constructs a comprehensive picture of how these beliefs manifest in daily school life. The result is a system that disproportionately identifies Black males as being “at risk” for failure and punishment, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy that can have lasting impacts on their academic and personal trajectories.

Key Factors Influencing Educators’ Perceptions

- Implicit biases and stereotypes about Black masculinity

- Lack of cultural competence and understanding of diverse backgrounds

- Overreliance on punitive disciplinary measures

- Limited exposure to positive representations of Black male success

- Systemic inequalities that reinforce negative expectations

Is it possible to change deeply ingrained beliefs and perceptions within the educational system? While challenging, Ferguson’s work suggests that increased awareness, targeted training, and a commitment to equity can help educators recognize and address their biases, leading to more positive outcomes for Black male students.

Challenging Prevailing Views: A Call for Educational Reform

“Bad Boys” presents a powerful challenge to prevailing views on the “problem” of Black males in American schools. By offering a richly textured account of the experiences of these young boys, Ferguson invites readers to reconsider their assumptions and approach the issue with fresh eyes. The book serves as a call to action for educators, parents, policymakers, and anyone concerned about the future of African American boys in our educational system.

Ferguson’s work highlights the need for comprehensive reform that addresses not just individual behaviors, but the systemic issues that contribute to the disproportionate disciplining of Black male students. This includes examining school policies, training programs for educators, curriculum design, and community engagement strategies.

Potential Areas for Educational Reform

- Implementing culturally responsive teaching practices

- Developing alternative disciplinary approaches that focus on restorative justice

- Increasing diversity among teaching staff and school leadership

- Creating mentorship programs that connect Black male students with positive role models

- Engaging families and communities in the educational process

- Addressing implicit bias through ongoing professional development for educators

How can schools move beyond punitive measures to create truly supportive environments for Black male students? By adopting a holistic approach that addresses both individual and systemic factors, educational institutions can work towards creating more equitable and inclusive spaces for all students.

The Intersectionality of Race, Gender, and Education

Ferguson’s research underscores the importance of considering the intersectionality of race and gender in educational contexts. The experiences of Black male students are shaped not only by their racial identity but also by societal expectations and stereotypes associated with masculinity. This intersection creates unique challenges that require nuanced understanding and targeted interventions.

By examining how race and gender interact within the school environment, Ferguson’s work contributes to a broader conversation about identity formation and social justice in education. It raises important questions about how schools can better support the development of positive identities for Black male students while challenging harmful stereotypes and expectations.

Key Aspects of Intersectionality in Education

- The impact of societal expectations of Black masculinity on academic performance

- The role of peer groups and community influences in shaping student identities

- The tension between school culture and Black male students’ cultural backgrounds

- The need for diverse representations of Black male success in curriculum and school leadership

- The importance of addressing both racial and gender-based biases in educational practices

Can schools effectively address the unique needs of Black male students without considering the intersection of race and gender? Ferguson’s research suggests that a more holistic approach is necessary to create truly inclusive and supportive educational environments.

Beyond the Classroom: The Broader Implications of Ferguson’s Research

While “Bad Boys” focuses primarily on the experiences of Black male students in elementary school, its implications extend far beyond the classroom. Ferguson’s work touches on broader societal issues, including the school-to-prison pipeline, systemic racism, and the long-term consequences of educational inequity.

The book serves as a valuable resource for professionals and students across various fields, including African-American studies, childhood studies, gender studies, juvenile studies, social work, and sociology. By examining the ways in which schools shape the next generation of African American boys, Ferguson’s research contributes to ongoing discussions about social justice, equity, and the role of education in society.

Broader Implications of Ferguson’s Research

- Understanding the roots of educational disparities and their long-term consequences

- Examining the role of schools in perpetuating or challenging systemic racism

- Exploring the connection between early educational experiences and later life outcomes

- Considering the impact of educational policies on Black communities

- Developing more effective interventions to support Black male student success

How can the insights from Ferguson’s research be applied to create positive change beyond the education system? By recognizing the far-reaching implications of educational inequity, stakeholders across various sectors can work together to address the root causes of disparities and create more just and equitable societies.

As we continue to grapple with issues of racial justice and educational equity, works like “Bad Boys” serve as crucial reminders of the ongoing challenges faced by Black male students in America’s public schools. By shedding light on the complex dynamics at play and offering a nuanced understanding of these young boys’ experiences, Ferguson’s research provides a foundation for meaningful change and a more inclusive educational future.

Public Schools in the Making of Black Masculinity (Law, Meaning, And Violence): Ferguson, Ann Arnett: 9780472088492: Amazon.com: Books

Statistics show that black males are disproportionately getting in trouble and being suspended from the nation’s school systems. Based on three years of participant observation research at an elementary school, Bad Boys offers a richly textured account of daily interactions between teachers and students to understand this serious problem. Ann Arnett Ferguson demonstrates how a group of eleven- and twelve-year-old males are identified by school personnel as “bound for jail” and how the youth construct a sense of self under such adverse circumstances. The author focuses on the perspective and voices of pre-adolescent African American boys. How does it feel to be labeled “unsalvageable” by your teacher? How does one endure school when the educators predict one’s future as “a jail cell with your name on it?” Through interviews and participation with these youth in classrooms, playgrounds, movie theaters, and video arcades, the author explores what “getting into trouble” means for the boys themselves. She argues that rather than simply internalizing these labels, the boys look critically at schooling as they dispute and evaluate the meaning and motivation behind the labels that have been attached to them. Supplementing the perspectives of the boys with interviews with teachers, principals, truant officers, and relatives of the students, the author constructs a disturbing picture of how educators’ beliefs in a “natural difference” of black children and the “criminal inclination” of black males shapes decisions that disproportionately single out black males as being “at risk” for failure and punishment.

She argues that rather than simply internalizing these labels, the boys look critically at schooling as they dispute and evaluate the meaning and motivation behind the labels that have been attached to them. Supplementing the perspectives of the boys with interviews with teachers, principals, truant officers, and relatives of the students, the author constructs a disturbing picture of how educators’ beliefs in a “natural difference” of black children and the “criminal inclination” of black males shapes decisions that disproportionately single out black males as being “at risk” for failure and punishment.

Bad Boys is a powerful challenge to prevailing views on the problem of black males in our schools today. It will be of interest to educators, parents, and youth, and to all professionals and students in the fields of African-American studies, childhood studies, gender studies, juvenile studies, social work, and sociology, as well as anyone who is concerned about the way our schools are shaping the next generation of African American boys.

Ann Arnett Ferguson is Assistant Professor of Afro-American Studies and Women’s Studies, Smith College.

Public Schools in the Making of Black Masculinity

Statistics show that black males are disproportionately getting in trouble and being suspended from the nation’s school systems. Based on three years of participant observation research at an elementary school, Bad Boys offers a richly textured account of daily interactions between teachers and students to understand this serious problem. Ann Arnett Ferguson demonstrates how a group of eleven- and twelve-year-old males are identified by school personnel as “bound for jail” and how the youth construct a sense of self under such adverse circumstances. The author focuses on the perspective and voices of pre-adolescent African American boys. How does it feel to be labeled “unsalvageable” by your teacher? How does one endure school when the educators predict one’s future as “a jail cell with your name on it?” Through interviews and participation with these youth in classrooms, playgrounds, movie theaters, and video arcades, the author explores what “getting into trouble” means for the boys themselves. She argues that rather than simply internalizing these labels, the boys look critically at schooling as they dispute and evaluate the meaning and motivation behind the labels that have been attached to them. Supplementing the perspectives of the boys with interviews with teachers, principals, truant officers, and relatives of the students, the author constructs a disturbing picture of how educators’ beliefs in a “natural difference” of black children and the “criminal inclination” of black males shapes decisions that disproportionately single out black males as being “at risk” for failure and punishment. Bad Boys is a powerful challenge to prevailing views on the problem of black males in our schools today. It will be of interest to educators, parents, and youth, and to all professionals and students in the fields of African-American studies, childhood studies, gender studies, juvenile studies, social work, and sociology, as well as anyone who is concerned about the way our schools are shaping the next generation of African American boys.

She argues that rather than simply internalizing these labels, the boys look critically at schooling as they dispute and evaluate the meaning and motivation behind the labels that have been attached to them. Supplementing the perspectives of the boys with interviews with teachers, principals, truant officers, and relatives of the students, the author constructs a disturbing picture of how educators’ beliefs in a “natural difference” of black children and the “criminal inclination” of black males shapes decisions that disproportionately single out black males as being “at risk” for failure and punishment. Bad Boys is a powerful challenge to prevailing views on the problem of black males in our schools today. It will be of interest to educators, parents, and youth, and to all professionals and students in the fields of African-American studies, childhood studies, gender studies, juvenile studies, social work, and sociology, as well as anyone who is concerned about the way our schools are shaping the next generation of African American boys. Anne Arnett Ferguson is Assistant Professor of Afro-American Studies and Women’s Studies, Smith College.

Anne Arnett Ferguson is Assistant Professor of Afro-American Studies and Women’s Studies, Smith College.

Bad Boys

Black males are disproportionately “in trouble” and suspended from the nation’s school systems. This is as true now as it was when Ann Arnett Ferguson’s now classic Bad Boys was first published. Bad Boys offers a richly textured account of daily interactions between teachers and students in order to demonstrate how a group of eleven- and twelve-year-old males construct a sense of self under adverse circumstances. This new edition includes a foreword by Pedro A. Noguera, and an afterword and bibliographic essay by the author, all of which reflect on the continuing relevance of this work nearly two decades after its initial publication.

“When Ann Ferguson published Bad Boys in 2000, it marked a watershed moment in educational research. The book’s insights on the role of schools in constructing, negotiating, and pathologizing Black masculinity were immediately recognized as a towering intellectual achievement. Twenty years later, as the academy and broader public finally begins to seriously engage the ‘school to prison pipeline’ discourse that Ferguson helped to advance and complicate, we still have much to learn from this theoretically rigorous and methodologically rich text. With a compelling new afterword and a brilliant new bibliographic essay, this new edition of Bad Boys is as urgent, relevant, and generative as the original was two decades ago. Anyone interested in the educational lives of Black boys owes an intellectual debt to Ann Ferguson. This book is a reminder of how large that debt is.”

Twenty years later, as the academy and broader public finally begins to seriously engage the ‘school to prison pipeline’ discourse that Ferguson helped to advance and complicate, we still have much to learn from this theoretically rigorous and methodologically rich text. With a compelling new afterword and a brilliant new bibliographic essay, this new edition of Bad Boys is as urgent, relevant, and generative as the original was two decades ago. Anyone interested in the educational lives of Black boys owes an intellectual debt to Ann Ferguson. This book is a reminder of how large that debt is.”

—Marc Lamont Hill, Temple University

“Teachers and future teachers should read Ferguson’s book, and so should all of those who are still unconvinced that our schools treat children differently when they are black.”

— Anthropology & Education Quarterly

“[Ferguson] leaves no doubt about the structural sources of schooling tensions and contradictions as she analyzes the complexity of Black masculinity in schools. These are racialized and gendered lessons for educational policy makers, classroom teachers, school disciplinary enforcers, and community members who want to make sense of the early school experiences of Black males.”

These are racialized and gendered lessons for educational policy makers, classroom teachers, school disciplinary enforcers, and community members who want to make sense of the early school experiences of Black males.”

— Gender & Society

“Ferguson succeeds in providing an intersectional analysis of how race, gender, and class dynamics combine in the institutional practices and treatment of the African‐American boys she follows. . . . Bad Boys is an engaging and important book that should be required reading for scholars and students studying education, race relations, criminal justice, social reproduction, or child psychology.”

—American Journal of Sociology

“Bad Boys is an incisive critique of the ways in which public schools help to create and shape perceptions of black masculinity. Beyond its rich ethnographic details, Ann Ferguson has crafted a compelling and insightful piece of scholarship. . . . Her work has widespread appeal and is readily applicable and informative for fields throughout the social sciences, especially criminal justice and sociology. ”

”

—Criminal Justice Review

Ann Arnett Ferguson was educated through high school in Kingston, Jamaica, and received her PhD in Sociology from the University of California, Berkeley. She taught primary school in Ghana, middle school in Tanzania, and Black Studies and Women’s Studies at Smith College in Massachusetts. She is retired and writing fiction in Portland, Oregon.

A Washington, D.C., Public School That’s Only for Boys

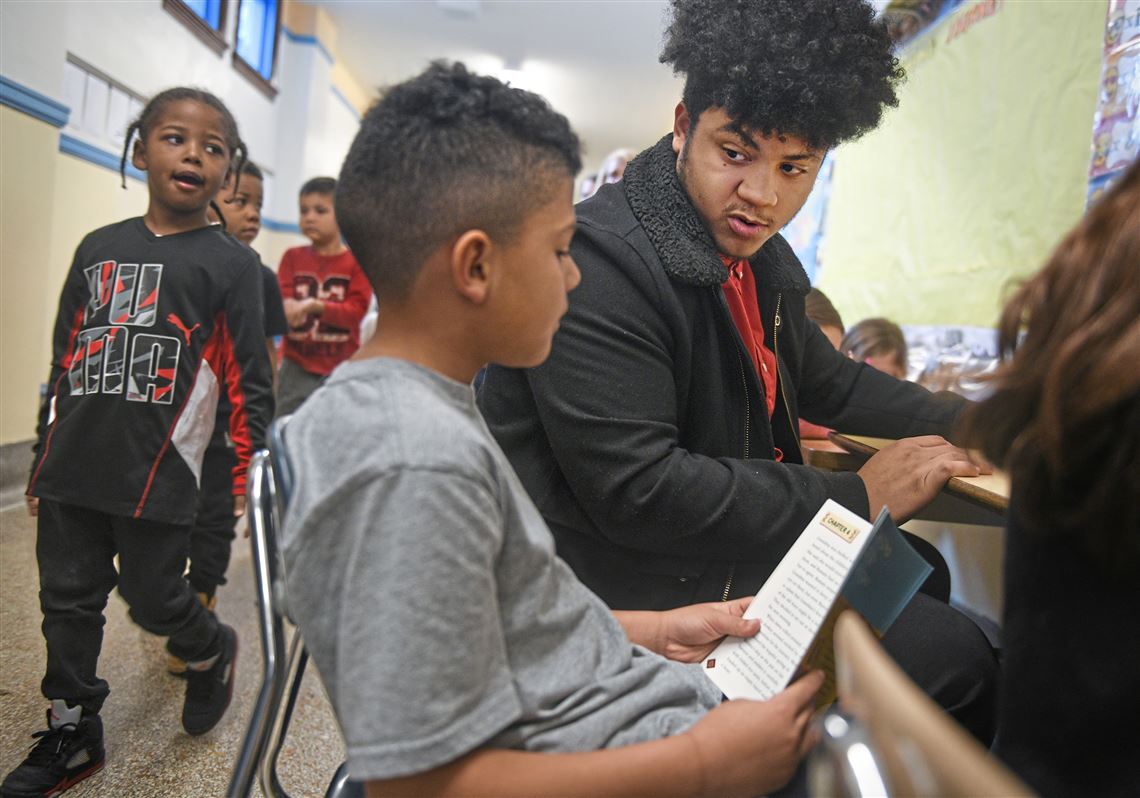

When Washington, D.C.’s school district announced earlier this year that it was launching an initiative to empower males of color, the press conference was filled with successful boys and young men whose stories exemplified the results that the district hopes to achieve for this student population—one that’s widely known to struggle academically.

A Latino teen spoke about becoming bilingual, reciting an impressive list of extracurriculars; another student proudly wore a University of Connecticut sweatshirt, reflecting his higher-education ambitions. Meanwhile, Kaya Henderson, the chancellor for the district’s schools, recounted the story of one recent D.C. Public Schools (DCPS) graduate who was accepted to five Ivy League colleges. (He chose Harvard.)

Meanwhile, Kaya Henderson, the chancellor for the district’s schools, recounted the story of one recent D.C. Public Schools (DCPS) graduate who was accepted to five Ivy League colleges. (He chose Harvard.)

Rather than reiterate a stereotypical narrative about low academic achievement among minority male students, the upbeat press conference focused on the strengths and potential within this cohort. The Empowering Males of Color Initiative, as it’s being called, is slated to devote $20 million, 500 volunteers, and a boys-only college-preparatory high school to creating more of these success stories.

But whether the plan will amount to an effective—and fair—solution is up in the air.

Based on the numbers, a targeted effort to increase academic achievement for boys of color seems warranted: 43 percent of D.C.’s public-school students are black and Latino males, and the high-school graduation rate for boys is 49 percent, compared to 66 percent for girls. (Nationally, the graduation rate is 78 percent for boys and 85 percent for girls. )

)

Single-sex schooling is not a “magic bullet … You have to have a lot of other things that make up quality education.”

To help it set up the proposed boy’s school, D.C. is turning to Chicago’s Urban Prep Academies—a well-known charter-school network for boys that touts its track record of sending 100 percent of its graduates to college. When it opened roughly a decade ago, the inaugural Urban Prep campus was the nation’s first all-boys charter high school; today, the network includes two additional Chicago locations. Aside from its focus on college prep and single-sex education, Urban Prep uses a curriculum that is, according to its website, “culturally relevant” to the experiences of its student body. “Everybody in the country wants Urban Prep to open an academy in their city,” said Henderson, who, it’s worth noting, attended Georgetown with Tim King, the network’s founder.

How exactly the new all-boys institution will fit into D.C.’s public-school system is still largely open to question. Although the school will operate under the DCPS umbrella, Henderson promised Urban Prep that it will have flexibility in developing the new program. (Unlike the Urban Prep campuses, the new all-boys school in D.C. will be a regular public school; charter schools in D.C. are governed separately.)

Although the school will operate under the DCPS umbrella, Henderson promised Urban Prep that it will have flexibility in developing the new program. (Unlike the Urban Prep campuses, the new all-boys school in D.C. will be a regular public school; charter schools in D.C. are governed separately.)

Still, Robert Simmons, the district’s Chief of Innovation and Research, emphasized in an interview that the new campus—which will be located east of the Anacostia river, in D.C.’s lowest-income neighborhoods—won’t stray far from the way regular public schools in the district are run. According to Simmons, its expectations will be similar to those applied at the six other selective high schools in the district. And despite the “nuances” in Urban Prep’s model, he said, the new campus will be different from other D.C. public schools only in its college-prep curriculum. Simmons, however, declined to elaborate on what the final product will look like, noting that Urban Prep is spearheading the design and has yet to publicize details on the plan.

Meanwhile, it’s unclear at this point how the application process will work. Speakers at the nearly hour-long press conference highlighted efforts to exclusively target minority students, but by law public institutions can’t enroll kids based on their race or ethnicity—and Simmons was quick to point out that “any boy can apply.”

“The jury is still out” on whether this is an effective solution. “But the jury currently says that it doesn’t do any harm.”

How the all-boys model will pan out is also uncertain. Single-gender public schools are rare, and most exist within a charter-school framework, as Urban Prep does in Chicago. In the regular public-school realm, some jurisdictions have toyed with the idea of creating single-gender classrooms or piloting single-sex schools on an experimental basis.

But proposing a regular public school for boys without a corresponding option for girls is highly unusual in the U.S. and risks violating Title IX, the law that requires gender equity at public education institutions.

The American Civil Liberties Union has already written a letter to D.C. officials asking for further information about the Urban Prep network and how Washington’s public-school system plans to adhere to Title IX in its initiative. DCPS, however, has not responded to the letter—and as of now it doesn’t plan to. If the district does refuse to voluntarily provide the requested information, the ACLU is prepared to use the available legal routes and submit a Freedom of Information request. “We really want these answers before we say, ‘you can’t do this,'” Monica Hopkins-Maxwell, the executive director of the the ACLU’s D.C. chapter, recently told me. “If it’s done in a certain way, it may not violate Title IX.”

Simmons reasoned that D.C. has “equivalent academic options for girls” at the district’s selective coed high schools, which typically require students to take a test for admission and are tailored around specific academic interests. But he declined to elaborate on how, exactly, those options will compensate for the all-boys school and ensure the district avoids violating equal-treatment laws. Simmons deferred to the D.C. Attorney General, Karl Racine, who is currently reviewing the plan and will soon release an opinion on its legality.

Simmons deferred to the D.C. Attorney General, Karl Racine, who is currently reviewing the plan and will soon release an opinion on its legality.

But the legality of the proposal is not the only issue at hand. Little consensus exists among researchers about the educational impact of limiting student populations to specific genders or races. “There’s all this evidence accumulating to suggest that diversity is important to learning,” said Richard Kahlenberg, an education researcher at the Century Foundation who helped design the relatively new tiered-admissions system used by Chicago’s selective public schools. “And it seems to me that gender is an element of that question.”

While some research reveals the positive outcomes associated with single-sex education, a 2011 story in Science magazine debunked many of the neurological justifications often cited to promote single-gender schools, calling these claims “pseudoscience.” The article also examined how effective all-boys schools are in increasing academic achievement, using Urban Prep as an example to emphasize that the positive impacts of single-sex education are debatable:

Underperforming children in [single-sex] schools often transfer out prematurely, which inflates final performance outcomes.

An example is Chicago’s Urban Prep Charter Academy for Young Men, a school whose high college admission rates have led to praise as a success story for [single-sex] education. However, when graduation rates at Urban Prep and similar schools are computed relative to freshman enrollment, they are comparable to those of other area public schools.

A 2014 analysis published by the American Psychological Association examined 184 studies concerning same-sex education and drew similar conclusions. The authors separated these reports into two categories: those that had control groups and those that didn’t. Notably, only the studies that lacked a control group (and were thus less reliable) produced results in favor of single-sex education, the distinction often very slight. Studies that used control groups found few remarkable differences between single-sex and coed schooling and, in some instances, showed that coed schools produced notably better results—especially in terms of girls’ achievement.

Indeed, many experts stress that the evidence is limited on the benefits of single-sex schooling. As Lea Hubbard, a sociology professor at the University of San Diego, who’s studied the effects of gender, race, and income on education, recently told me, single-gender education is not a “magic bullet … You have to have a lot of other things that make up quality education.”

In other words, the limited scientific agreement on whether single-sex education is helpful, harmful, or something in between—along with the varying research on other types of student diversity—means it’s difficult to deduce whether the D.C. proposal is a good idea. Even its backers acknowledge the plan’s uncertainty: “The jury is still out,” Simmons said. “But the jury currently says that it doesn’t do any harm.”

Why public schoolboys like me and Boris Johnson aren’t fit to run our country | Private schools

I had a feeling I couldn’t immediately place. I wanted to go out but wasn’t allowed. Shelves were emptying at the nearest supermarket and instead of fresh fruit and vegetables I was eating British comfort food – sausages and mash, pie and beans. My freedom to make decisions like an adult was limited. I wondered when I’d see my mum again.

My freedom to make decisions like an adult was limited. I wondered when I’d see my mum again.

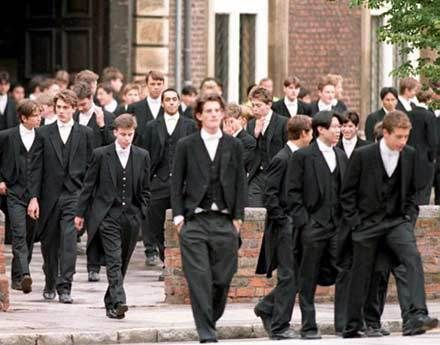

March 2020, first week of the first lockdown: I was 53 years old and felt like I was back at boarding school. Which wouldn’t have mattered, but for the fact that at a time of national crisis my generation of boarding-school boys found themselves in charge.

My first night at Pinewood school was two days after my eighth birthday in January 1975. A term earlier David Cameron had left his family home for Heatherdown preparatory school in Berkshire, while also in 1975, at the age of 11, Alexander Johnson was sent to board at Ashdown House in East Sussex. This means I know how two of the past three British prime ministers were treated as children and the kind of men their schools wanted to make of them. I know neither of these men personally but I do know that they spent the formative years of their childhood in boarding schools being looked after by adults who didn’t love them, because I did too. And if the character of our leaders matters then I’m in possession of important information.

And if the character of our leaders matters then I’m in possession of important information.

At the age of 13, after prep school, Cameron and Johnson progressed to Eton. I went on to Radley College near Oxford. The exact school picked out by the parents didn’t really matter, because the experience was designed to produce a shared mindset. They were paying for a similar upbringing with a similar intended result: to establish our credentials for the top jobs in the country. We were being trained for leadership, or if not to lead then to earn. The most convincing reason to go to a private school remains to have gone to a private school, with the prizes that are statistically likely to follow.

It is noticeable, and often noticed, that something immature and boyish survives in men like Cameron and Johnson as adults. They can never quite carry off the role of grownup, or shake a suspicion that they remain fans of escapades without consequences. They look confident of not being caught, or not being punished if they are. Cameron has his boyishly unlined face and Johnson his urchin’s unbrushed hair, and his arch schoolboy’s vocabulary.

Cameron has his boyishly unlined face and Johnson his urchin’s unbrushed hair, and his arch schoolboy’s vocabulary.

But what kind of boyhood was it, in our paid-for rooms in those repurposed mansions that housed our schools? What of the distant past still works in us as adults and can we pass on the harm to others? Are we the right people to steer the country, either clear of trouble or in the direction of sunlit uplands? The answer to these questions depends on lessons learned at an impressionable age. Unless, of course, we learned nothing. And no one pays hundreds of pounds a term, even in the late 70s, to learn nothing.

I remember the feeling of desolate homesickness: abruptly, several times a year, our attachments to home and family were broken

One of the first things we learned – or felt – at prep school was a deep, emotional austerity, starting from the moment the parents drove away. That first night, and on other nights to come, the little men in ties and jackets reverted to the little children they really were – in name-taped pyjamas with a single soft toy (also name-taped), blubbing themselves to sleep and wetting their beds.

I remember the feeling of desolate homesickness: abruptly, several times a year, our attachments to home and family were broken. We lost everything – parents, pets, toys, younger siblings – and we could cry if we liked but no one would help us. So that later in life, when we saw other people cry, we felt no great need to go to their aid. The sad and the weak were wrong to show their distress, and we learned to despise the children who blubbed for their mummies. The cure was to stop crying and forget that life beyond the dormitories and classrooms existed. Concentrate instead on the games pitches and the dining hall and the headmaster’s study. By force of will we made ourselves complicit in a collective narrowing of vision.

In Richard Denton’s BBC documentary Public School, filmed at Radley College in 1979, the Radley headmaster Dennis Silk tells a daunted audience of new boys that they’re about to pick up “the right habits for life”. Among these habits was cultivation of the stiff upper lip. We could be ourselves – homesick, vulnerable, lovelorn and frightened – or, with practice at putting up a front, we could pretend to embody the idealised national character. We could perform being loyal and robust and self-reliant. Wearing a commendably brave face we could distance our feelings, growing the “hardness of heart of the educated”, as identified by Mahatma Gandhi from his dealings with the English ruling class.

We could be ourselves – homesick, vulnerable, lovelorn and frightened – or, with practice at putting up a front, we could pretend to embody the idealised national character. We could perform being loyal and robust and self-reliant. Wearing a commendably brave face we could distance our feelings, growing the “hardness of heart of the educated”, as identified by Mahatma Gandhi from his dealings with the English ruling class.

Beard at Radley College boarding school in 1984. Photograph: Sally Lines

This wasn’t healthy. In her 2015 book, Boarding School Syndrome, psychoanalyst Joy Schaverien describes a condition now sufficiently recognised to merit therapy groups and an emergent academic literature. The symptoms are wide-ranging but include, ingrained from an early age, emotional detachment and dissociation, cynicism, exceptionalism, defensive arrogance, offensive arrogance, cliquism, compartmentalisation, guilt, grief, denial, strategic emotional misdirection and stiff-lipped stoicism. Fine fine fine. We’re all doing fine.

Fine fine fine. We’re all doing fine.

We adapted to survive. We postured and lied, whatever it took. Abandoned, alone, England’s future leaders needed to fit in whatever the cost, and we were not needy, no sir. We could live without, and we convinced ourselves early that we had no great need of love, in either direction. Acting like a grownup meant needing no one.

Discouraged from crying out for help, frightened of complaining or sneaking, we developed a gangster loyalty to self-contained cliques, scared to death of being cast out as we had been from home. Of being cast out again. In the absence of family we kept in with our chums, but also ingratiated ourselves with the teachers: God knows what might come next after abandonment if we kicked up a fuss.

From the teachers we learned about mockery and sarcasm as techniques for social control, with our boy hierarchies regulated by banter, ranging from a sharp remark to a knuckle in the crown of the head. Attack was the best form of defence, and ridicule was honed as a deeply conservative force, controlling by means of fear, either of being the joke or of not getting the joke. There was plenty of fear to go round. The author Paul Watkins, in his memoir Stand Before Your God, remembers at Eton the huge amount of energy, in the time of Cameron and Johnson, that went into “teasing and ignoring people”. “I felt a harshness that I’d never felt before.”

There was plenty of fear to go round. The author Paul Watkins, in his memoir Stand Before Your God, remembers at Eton the huge amount of energy, in the time of Cameron and Johnson, that went into “teasing and ignoring people”. “I felt a harshness that I’d never felt before.”

George Orwell, during his time at prep school, remembers being ridiculed out of an interest in butterflies. The banter that day must have been immense. Nothing was sacred, and once we found out what another boy took most seriously we were ready to strike, when necessary, at its core. Our most effective defence was therefore to act as if we took nothing very seriously at all.

We learned to stay detached, some would say cold – “You had to have a coldness in yourself,” writes Watkins. “Of all the rules I learned and later threw away, this one I kept. If you did not know it, you could get hurt very badly at a place like Eton.”

Later in life, these unwritten school rules could infect every type of relationship. Prematurely detached from our parents, we had a preference for abandoning others before getting abandoned ourselves. Jump ship. Also, to be on the safe side, keep an emotional reserve.

Prematurely detached from our parents, we had a preference for abandoning others before getting abandoned ourselves. Jump ship. Also, to be on the safe side, keep an emotional reserve.

Prof Diana Leonard, who established the Centre for Research on Education and Gender at the University of London, published research in 2009 showing that boys from single-sex schools were more likely to be divorced or separated from their partner by their early 40s. And mental health professionals, like Schaverien, are convincing in their explanation that those years of disconnection mean we expect too much, our fantasies rarely surviving contact with reality. Making up for lost time, for example, we want sex but come to resent women for our weakness for sex – as adults, erotic dependence becomes a new form of vulnerability to be doubted and denied. Why couldn’t women be more like our boyhood Athena posters?

At school we tried not to feel foolish, angry, loving, stupid, sad, dependent, excited or demanding. We were made wary of feeling, full stop. By comparison, children not blessed with a private education must be fizzing with uncontrolled emotions and therefore insufferably weak. How did the schools teach us this sense of superiority? The language was always chipping away – in the documentary Public School the boys casually refer to “the lower orders”, as if to a species difference, reptiles considering insects. In our isolation we learned that we were special. Everyone else was less special and often stupid – school was where we went, aged eight, to learn to despise other people.

We were made wary of feeling, full stop. By comparison, children not blessed with a private education must be fizzing with uncontrolled emotions and therefore insufferably weak. How did the schools teach us this sense of superiority? The language was always chipping away – in the documentary Public School the boys casually refer to “the lower orders”, as if to a species difference, reptiles considering insects. In our isolation we learned that we were special. Everyone else was less special and often stupid – school was where we went, aged eight, to learn to despise other people.

Pinewood school in 1975, the year Richard Beard first attended aged eight. Photograph: Henry Morritt

Cameron, Johnson and I absorbed attitudes once familiar to Orwell, who was confronted with some realities about his Eton education when documenting the living conditions of working-class households in Lancashire and Yorkshire. “Common people seemed almost sub-human,” Orwell writes in The Road to Wigan Pier. “They had coarse faces, hideous accents, and gross manners… and if they got half the chance they would insult you in brutal ways.” Alien and dangerous, the working class evoked “an attitude of sniggering superiority punctuated by bursts of vicious hatred”.

“They had coarse faces, hideous accents, and gross manners… and if they got half the chance they would insult you in brutal ways.” Alien and dangerous, the working class evoked “an attitude of sniggering superiority punctuated by bursts of vicious hatred”.

Anyone underestimating the durability of this divide should consider the evidence of the Radley College swimming pool, circa 1980. A story used to circulate that the pool was a yard shorter than a standard pool, so that no local swimming club would want to use it for practice or competitive events. Christopher Hibbert’s history of Radley, No Ordinary Place, corrects this myth: the pool was deliberately designed a yard longer. The same reasoning applied. The locals shouldn’t be encouraged. Typically, in a summer term ending in early July, we didn’t swim in it much anyway.

In the early 80s, Radley’s non-teaching staff were known as College Servants. We had cleaners, chefs, groundsmen, bit-part players and comic mechanicals. They represented the proles, the plebs, the oiks, the yokels, the townies and the crusties (a term Johnson continued to use 40 years later). Our special language had its range of words to set these unfamiliar animals apart, meaning people not like us, and if you didn’t know the language you were probably one of them. As Orwell doubles-down in Nineteen Eighty-Four: “The proles are not human beings.”

They represented the proles, the plebs, the oiks, the yokels, the townies and the crusties (a term Johnson continued to use 40 years later). Our special language had its range of words to set these unfamiliar animals apart, meaning people not like us, and if you didn’t know the language you were probably one of them. As Orwell doubles-down in Nineteen Eighty-Four: “The proles are not human beings.”

In his autobiography, For the Record, David Cameron admits that about Brexit he “did not fully anticipate the strength of feeling that would be unleashed both during the referendum and afterwards”. Of course he didn’t. Strong feelings were involved, and also the common people. He was floundering in a pair of blind spots, to emotion and the British public. He gorged on a double helping of ignorance undisturbed since his schooldays.

Looking now at old school photos, I find I can count the darker faces on the fingers of one hand. At Pinewood we had two brothers recently arrived from Nigeria, and the son of an Indian doctor who lived not far from my parents in Swindon. The only other dark faces we saw were in our Saturday-night films, in Zulu and Young Winston, where savage natives were subdued by the civilising force of white British warriors. Did that turn us into racists? Yes, I think it did.

The only other dark faces we saw were in our Saturday-night films, in Zulu and Young Winston, where savage natives were subdued by the civilising force of white British warriors. Did that turn us into racists? Yes, I think it did.

In the holidays I’d go to the post office on Victoria Road, to collect Mum’s child benefit, and when the British Asian post office worker stamped the book I was immensely pleased with myself for acting as if he were just like anyone else. At Radley one boy in our year was possibly mixed race – we didn’t really know but mocked him for it anyway – and the two of us played in the same rugby team. In my end-of-year sports reports I make feeble gags about Brownian motion and his “blacking” of other players. I don’t even know what that means, beyond the racial slur. The supervising editor of the school magazine, a teacher, saw nothing in need of editorial attention. And why would he? The racism was institutional – with the evidence currently available online in the school’s digitised archive.

Girls, swots, oiks, wogs and queers were synonymous with weakness, to be joshed without mercy by the strong

I find the son of the Indian doctor on LinkedIn – Ravi is successful in business, though he asks me not to use his real name. Whatever I think about private schools and racism, what does he think? Initially he’s cautious. He writes back that “frankly there are some very bad memories of that time that are very painful”.

As first-generation immigrants, he tells me later by phone, his Indian parents wanted to give him a good education. Overall, Pinewood was “pretty decent”; his public school less so. He asks me not to name it.

“I was called a wog and a Paki. There was the National Front.”

In his school as at mine, public speaking was encouraged – good for the confidence – and one boy was “passionate about the National Front”. Ravi regrets sitting in the audience and at the end of a hate speech clapping politely, demonstrating the good manners he’d been educated to value. There was also racism from the teachers, in remarks that casually encompassed Ravi’s father and family.

There was also racism from the teachers, in remarks that casually encompassed Ravi’s father and family.

Boris Johnson at Eton in 1979. In 2020, two-thirds of his full cabinet were privately educated. Photograph: Ian Sumner/Rex/Shutterstock

Our schoolboy vocabulary, with its stock of disparaging words, expanded to include everyone who deserved our scorn, like poofs and homos. As long as we weren’t girls, swots, oiks, wogs or queers, we could be jolly decent chaps. All those other categories were synonymous with weakness, to be joshed without mercy by the strong. And if a boy struggled with the spontaneity of banter, he could memorise jokes about the Irish, who were unbelievably thick. We laughed at anyone not like us, and the repertoire on repeat included gags about slaves and nuns and women hurdlers. One September, after a boy came back from a holiday in Australia, we had jokes about Aborigines. We internalised this poison like a vaccine, later making us insensitive as witnesses to all but the most vicious instances of discrimination. Everyone who was not us, a boy at a private boarding school from the late 70s to the early 80s, was beneath us. Obviously, we too were a minority, but of all the minorities we were the most important. Of course we were. We’d end up running the country.

Everyone who was not us, a boy at a private boarding school from the late 70s to the early 80s, was beneath us. Obviously, we too were a minority, but of all the minorities we were the most important. Of course we were. We’d end up running the country.

Single-minded ambition became acceptable as a way of deadening the self. Get elected president of the debating society. Edit the school magazine. Lobby to become head of house, head prefect. Join a milkround company, get a column on a national newspaper, write a book. For the worst afflicted, at the high end of the greasy pole, become prime minister. The drive for success was an ongoing plea for attention and affection, a condition described by Lucille Iremonger in her book Fiery Chariot as the Phaeton complex. In Greek mythology Phaeton was a frustrated child of the sun god Helios, who insists on driving his father’s chariot just for one day. He crashes the chariot, turning much of Africa into desert.

According to Iremonger, a hunger for power is the tragic fate of children abandoned by their parents, and she developed her theory from a study of British prime ministers between 1809 and 1940. No prizes for guessing where most of them were educated, and many former boarders can be recognised as Phaetons.

No prizes for guessing where most of them were educated, and many former boarders can be recognised as Phaetons.

In his book The Old Boys, David Turner has the statistics for the “highly disproportionate share” of public school alumni in the top jobs of the UK. These figures come from 2014, to include boys at school at the same time as me in their middle-aged professional prime: “seven in 10 senior judges, six in 10 senior officers in the armed forces, and more than half the permanent secretaries, senior diplomats and leading media figures”. Seventeen out of 27 members of Johnson’s full cabinet in 2020 went to private school. Of the more visible recent political buccaneers, leading English private schools have sent out Rees-Mogg, Hunt, Mitchell, Cash, Redwood and Cummings: English boys with English minds.

A follow-up report by the Sutton Trust and Social Mobility Commission, Elitist Britain 2019, paints a mostly unchanged picture. Private schools account for nearly 70% of the judges and barristers in the country. To this list can be added more than 50% of bishops and ministers of state and lord lieutenants and the England cricket team, these doors not even half open to anyone else.

To this list can be added more than 50% of bishops and ministers of state and lord lieutenants and the England cricket team, these doors not even half open to anyone else.

Johnson was any boy who started boarding in 1975, only more so, because not growing up was openly a part of his act

When deciding on a private school education for his children, my dad must have envisaged useful connections for life that seem psychologically plausible as well as professionally desirable: a segregated elite united by a common uncommon experience. Cameron surrounded himself with like-minded people – of the six men who worked on the Conservative Party Manifesto in 2014, five had been to Eton. The other was an old boy of St Paul’s. Sonia Purnell, Johnson’s biographer, says Johnson doesn’t have friends – his younger brother was best man at his first wedding – but he knows what kind of person makes him feel comfortable. He remains loyal to boys’ school boys like his friend Darius Guppy (who famously asked Johnson for the address of a fellow journalist so he could have him beaten up) and Cummings, rebels but public school rebels. Or loyal at least for a while. Once Johnson and Cummings fell out, each was right to be frightened of the other. Their schooling was more powerful in them than any self-projection as icon or iconoclast: they knew how to hurt their own.

Or loyal at least for a while. Once Johnson and Cummings fell out, each was right to be frightened of the other. Their schooling was more powerful in them than any self-projection as icon or iconoclast: they knew how to hurt their own.

In her biography, Purnell calls Johnson “an original – the opposite of a stereotype, the exception to the rule”. Not quite. He was any boy who started at a private boarding school in 1975, only more so because not growing up was openly a feature of his performance. He flaunted shamelessly what the rest of us tried to conceal: he was chaotic, unformed, cruel, slapdash, essentially frivolous. When he messed up he was just a boy, with his boyishly ruffled hair, and expected to be excused.

Cameron likewise turned his back on the mess he’d made with the serenity of a public school boy whose ancestors had been public school boys too. Between the lectern and the door of yet another temporary home Cameron hummed a happy tune, pretending to be fine. All is well, thank you and goodnight. Possibly he’d been a bit naughty, but luckily England was arranged in such a way as to protect his own best interests. Of course it was. Boys like us had arranged it.

Possibly he’d been a bit naughty, but luckily England was arranged in such a way as to protect his own best interests. Of course it was. Boys like us had arranged it.

In the end we can’t take anything seriously.

In earlier generations, Orwell and others like him were exposed by war and other calamities to a seriousness that grew their stunted selves and tempered the isolated and ironic cult of an English private education. They were goaded by events into compassion, so that sooner or later, Orwell believed, even in “a land of snobbery and privilege, ruled largely by the old and silly”, England would brush aside the obvious injustice of the public schools.

The wait goes on. Maybe in 40 years’ time, assuming the country survives Brexit and Covid, a more enlightened nation might look back on Cameron and Johnson as a self-erasing supernova, a final bright flare and a burning out, the dying of the public school light in a burst of corruption and incompetence so spectacular the glimmer will be visible from space.

Anyone betting on that outcome, at any point in the past 600 years, would have lost.

This is an edited extract from Sad Little Men by Richard Beard (Harvill Secker, £16.99). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply

Richard Beard Q&A: ‘This is a very private-school idea – you just have to live with social injustice’

Author Richard Beard. Photograph: Urszula Soltys

How has your schooling affected you?

My relationship with my own emotions was distorted from the moment it was taken as gospel truth that it was good for me to be separated from my family aged eight. You’re doing something that feels terrible, but everyone tells you it’s good. That leads to further dislocations, which allow individuals to become fractured, divided, and very good at leading a double life.

Boris Johnson and David Cameron attended similar schools at a similar time. How do you think it shaped them?

How do you think it shaped them?

In so many ways. Almost every day I read the paper and think, yes, I recognise that. Recently, it’s the idea that you just have to live with stuff – with Covid, for example. Just as at school you just had to live with your parents leaving you behind, with the daily authoritarianism, with not going home for weeks at a time. This is a very private-school idea – you just have to live with social injustice.

There’s also the extensive training in dissembling and putting up a front. I don’t get any sense of authenticity from them, or genuine empathy. At some point, you start feeling sorry for them.

Do you feel sorry for them?

Well I hope it’s there in the title of the book – it’s not just the pejorative name-calling of sad little men. I know that they had to create their own coping mechanisms. And those coping mechanisms are what you see in these behaviours, which do seem to me to start out from the sadness of little boys out of their depth, but who learned early in their lives how to hide that.

Johnson has been described as confusing and contradictory, but you say that’s precisely what boarding school produces… shapeshifters with fluid identities.

That connection is made quite clearly by John le Carré – he often links this type of education to the vocation of being a spy. I do think it’s different now, because we’ve grown up through a period of peace and prosperity, and we haven’t had that tempering that previous generations have had, when confronted by major world events – being goaded into seriousness, but also into empathy for other people in the country.

You’re pretty unambiguous about the hellishness of boarding school. Why do parents send their children to these places?

It’s not hellish on a daily basis. On the surface, it seems quite the opposite, especially to the parents. When you see the tennis courts and the swimming pools it looks fantastic. The problems are underneath the surface.

But a lot of these parents have gone through it themselves, so they are well aware of the damage it creates…

If you’re now in a position to send your children to private school, it means you either managed your inheritance wisely or you’re a QC or an investment banker or the prime minister and you can say: “What a great success!” It’s very hard to fight back against that surface, against that lie.

Did you ever consider sending your kids to private schools?

No. I wanted the kids to be coming home at night, and I wanted them to be in co-education.

Did that extend to sending them to state schools?

I lived abroad a lot, where they were in lycées, French-speaking schools. In this country, to keep the language going, that meant finding what’s now a free school, so a state school but not a classic comprehensive.

Do you feel that by writing this book, and facing up to your schooling, you’ve exorcised it in some way?

I think facing and unpacking a past life is the antidote to some of its effects. But I was deeply formed by these experiences. The lies create habits for life which are, in many cases, detrimental to living well, and that takes a long time to undo.

Interview by Killian Fox

Public Schools in the Making of Black Masculinity

Statistics show that black males are disproportionately getting in trouble and being suspended from the nation’s school systems. Based on three years of participant observation research at an elementary school, Bad Boys offers a richly textured account of daily interactions between teachers and students to understand this serious problem. Ann Arnett Ferguson demonstrates how a group of eleven- and twelve-year-old males are identified by school personnel as “bound for jail” and how the youth construct a sense of self under such adverse circumstances. The author focuses on the perspective and voices of pre-adolescent African American boys. How does it feel to be labeled “unsalvageable” by your teacher? How does one endure school when the educators predict one’s future as “a jail cell with your name on it?” Through interviews and participation with these youth in classrooms, playgrounds, movie theaters, and video arcades, the author explores what “getting into trouble” means for the boys themselves. She argues that rather than simply internalizing these labels, the boys look critically at schooling as they dispute and evaluate the meaning and motivation behind the labels that have been attached to them.

Based on three years of participant observation research at an elementary school, Bad Boys offers a richly textured account of daily interactions between teachers and students to understand this serious problem. Ann Arnett Ferguson demonstrates how a group of eleven- and twelve-year-old males are identified by school personnel as “bound for jail” and how the youth construct a sense of self under such adverse circumstances. The author focuses on the perspective and voices of pre-adolescent African American boys. How does it feel to be labeled “unsalvageable” by your teacher? How does one endure school when the educators predict one’s future as “a jail cell with your name on it?” Through interviews and participation with these youth in classrooms, playgrounds, movie theaters, and video arcades, the author explores what “getting into trouble” means for the boys themselves. She argues that rather than simply internalizing these labels, the boys look critically at schooling as they dispute and evaluate the meaning and motivation behind the labels that have been attached to them. Supplementing the perspectives of the boys with interviews with teachers, principals, truant officers, and relatives of the students, the author constructs a disturbing picture of how educators’ beliefs in a “natural difference” of black children and the “criminal inclination” of black males shapes decisions that disproportionately single out black males as being “at risk” for failure and punishment.

Supplementing the perspectives of the boys with interviews with teachers, principals, truant officers, and relatives of the students, the author constructs a disturbing picture of how educators’ beliefs in a “natural difference” of black children and the “criminal inclination” of black males shapes decisions that disproportionately single out black males as being “at risk” for failure and punishment.

Bad Boys is a powerful challenge to prevailing views on the problem of black males in our schools today. It will be of interest to educators, parents, and youth, and to all professionals and students in the fields of African-American studies, childhood studies, gender studies, juvenile studies, social work, and sociology, as well as anyone who is concerned about the way our schools are shaping the next generation of African American boys.

Ann Arnett Ferguson is Assistant Professor of Afro-American Studies and Women’s Studies, Smith College.

California All-Male High Schools

- Home

- California High Schools

- California All-Male High Schools

Map of California All-Male High Schools

| School | Type | City | Students | Student to Teacher Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Servite High School | Private | Anaheim, CA | 905 | 15. 0 0 |

Greenacre Homes | Private | Atkinson Rd, CA | 44 | 15.0 |

St John Bosco High School | Private | Bellflower, CA | 842 | 16.0 |

Mesivta Of Greater Los Angeles | Private | Calabasas, CA | 60 | 6.0 |

Army & Navy Academy | Private | Carlsbad, CA | 264 | 10. 0 0 |

Jesuit High School | Private | Carmichael, CA | 1,072 | 17.0 |

De La Salle High School | Private | Concord, CA | 1,038 | 15.0 |

Crespi Carmelite High School | Private | Encino, CA | 494 | 14.0 |

St Francis High School | Private | La Canada Flintridge, CA | 662 | 22. 0 0 |

Loyola High School | Private | Los Angeles, CA | 1,242 | 14.0 |

Verbum Dei High School | Private | Los Angeles, CA | 312 | 11.0 |

Yeshiva Gedolah Of Los Angeles | Private | Los Angeles, CA | 77 | 6.0 |

Yeshiva Ohr Elchonon Chabad – West Coast | Private | Los Angeles, CA | 129 | 7. 0 0 |

Yeshivat Ohr Chanoch | Private | Los Angeles, CA | 31 | 4.0 |

Yula Boys High School | Private | Los Angeles, CA | 170 | 6.0 |

Milhous School – Nevada City | Private | Nevada City, CA | 33 | 9.0 |

Milhous School – Sacramento | Private | Nevada City, CA | 16 | 5. 0 0 |

Don Bosco Technical Institute | Private | Rosemead, CA | 394 | 12.0 |

Gates Of Learning Center | Private | Roseville, CA | 14 | 14.0 |

Palma School | Private | Salinas, CA | 428 | 15.0 |

St Augustine High School | Private | San Diego, CA | 736 | 13. 0 0 |

Archbishop Riordan High School | Private | San Francisco, CA | 691 | 14.0 |

Stuart Hall High School | Private | San Francisco, CA | 203 | 7.0 |

Junipero Serra High School | Private | San Mateo, CA | 875 | 12.0 |

Plumfield Academy | Private | Sebastopol, CA | 20 | 7. 0 0 |

St Michael’s Prep School | Private | Silverado, CA | 64 | 4.0 |

Archbishop Hanna High School | Private | Sonoma, CA | 107 | 5.0 |

Valley Torah High School | Private | Valley Village, CA | 120 | 6.0 |

Download this data as an Excel or CSV Spreadsheet | ||||

View Categories of Schools in California

California Schools by City, District, and County

California Private Schools by Type

View High School Statistics for California

California Public School Statistics

California Private School Statistics

90,000 Education history: from the first schools of Russia to the Soviet ones

At various times, Russian schools taught lessons in literacy and drawing, physics and logic, astronomy and Greek. Classes were led first by clergymen, and later by subject teachers. The Kultura.RF portal tells how the education system in Russia has changed over the course of ten centuries.

Classes were led first by clergymen, and later by subject teachers. The Kultura.RF portal tells how the education system in Russia has changed over the course of ten centuries.

First schools

Nikolay Bogdanov-Belsky. Inspiration (fragment). 1910. Private collection

Ivan Vladimirov.At the sexton’s reading and writing lesson (fragment). 1913. Private collection

Nikolay Bogdanov-Belsky. Composition (fragment). 1903. State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

“Before the Slavs, when they were pagans, had no letters, but [counted] and guessed with the help of lines and cuts” …

After the baptism of Rus in 988, the state faced the task of “instilling” a new religion, and for this it was necessary to teach the population to read and write.The Slavic alphabet appeared – it was created specifically for the translation of church texts by the Greeks Cyril and Methodius. The first schools were opened in Kiev, Novgorod, Smolensk, Suzdal, Kursk. Scientists have established that it took from 50 to 100 years for writing to spread widely among the nobility, clergy, individual merchants and artisans.

Scientists have established that it took from 50 to 100 years for writing to spread widely among the nobility, clergy, individual merchants and artisans.

In the XX century, during excavations in Novgorod, more than a thousand birch bark letters were found. Among them are the letters and drawings of Onfim, a boy of six or seven years old who lived in the 13th century.According to the researchers, the child lost his exercises. Most likely, Onfim moved from writing on a wax tablet to writing on a birch bark. At first, the students wrote out the full alphabet, after – the syllables, and then copied fragments from the Psalter and business formulas like “Collect debts from Dmitr”, “Bow from Onfim to Danila.”

According to the historian Vasily Tatishchev, Prince Roman Smolensky opened several schools in Smolensk. They studied Greek and Latin. In the Suzdal principality, Prince Constantine was engaged in education.

In the Principality of Suzdal, Prince Constantine (son of Vsevolod III) collected a library of Greek and Slavic books, ordered translations from Greek into Russian and bequeathed – in 1218 – his house in Vladimir and part of the income from the estate to the school in which they were supposed to teach Greek.

Teaching in pre-Petrine Russia

Nikolay Bogdanov-Belsky. The future monk (fragment). 1889. Latvian National Museum of Art, Riga

Nikolay Bogdanov-Belsky.Sunday reading in a rural school (fragment). 1895. State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

Nikolay Bogdanov-Belsky. At the school door (detail). 1897. State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

You can learn about the education system in the Moscow state from the “ABCs” – collections of textbooks and school rules. In the 17th century, schools for boys aged 8–12 were kept by clergy. The training proceeded unhurriedly: they studied the alphabet, then they began to read the Book of Hours, the Psalter, the Acts of the Apostles and the Gospel, then moved on to writing.

In high school, they mastered the “seven free arts”: grammar, dialectics, rhetoric, church singing, arithmetic, surveying, which included information on geometry and geography, and star studies, that is, astronomy. Of the foreign languages, only Latin and Greek were held in high esteem – they were taught to future church ministers, officials and diplomats.

The elder children of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich studied Latin, Greek and Polish languages and music under the guidance of the poet and theologian Simeon Polotsky.But the education of the youngest son – the future Peter I – was not given due attention. By this time, Alexei Mikhailovich had died, and the child from his second marriage, along with his mother, was in disgrace.

Peter began to study writing, it seems, at the beginning of 1680 and never knew how to write in a decent handwriting. Zotov (former clerk Ivan Zotov, assigned to the tsarevich. – Ed.) As a teaching aid used illustrations brought to Moscow from abroad, introduced Peter to the events of Russian history.

The Dutchman Timmerman taught Peter to use the astrolabe brought from abroad (the oldest astronomical instrument. – Ed. ). Another Dutchman from the German Quarter named Karsten-Brant taught an inquisitive young man to maneuver on a boat and control the sails.

Schools under Peter I

Nikolay Bogdanov-Belsky. Pupils (fragment). 1901. Saratov State Art Museum named after A.N. Radishcheva, Saratov

Alexey Strelkovsky.Rural school (fragment). 1872. State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Alexey Venetsianov. Portrait of Kirill Ivanovich Golovachevsky, inspector of the Academy of Arts, with three pupils (fragment). 1911. State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

Peter I understood the need for professional education. Therefore, in 1701 in Moscow, by his decree, the School of Mathematical and Navigational Sciences was opened. Young men of different classes, aged 12 to 20, studied there. After mastering literacy, arithmetic, geometry and trigonometry, students of low birth, as a rule, entered the service, and the offspring of noble families went to the “upper school”, where they studied German, astronomy, geography, navigation, fortification.

At the same time, educational institutions appeared that graduated metallurgical workers, doctors, clerks, engineers, chemists, artillerymen, translators. In 1714, elementary digital schools appeared – they focused on arithmetic and geometry.

In 1714, elementary digital schools appeared – they focused on arithmetic and geometry.

For the “provincial nobility and clerical rank, clerk and clerk children from 10 to 15 years old” was introduced training duty. She displeased the parents, since merchants and artisans traditionally taught the heirs to read and write themselves, while at the same time they taught trade.Because of this, the merchants could not transfer the family business to their children in a timely manner. The clergy sent their offspring to religious episcopal schools – they opened in all dioceses in 1721.

One of the last brainchildren of Peter was the Academy of Sciences. The emperor established it in 1724. However, she began work after the death of the emperor – at the end of 1725. The academy included a gymnasium and a university.

The University is a collection of learned people who teach young people the high sciences, like theology and jurisprudence of prudence (rights to art), medicine, philosophy, that is, to what state they have now reached.

Read also:

Educational reform of Catherine II

Vasily Perov. The arrival of the schoolgirl to her blind father (fragment). 1870. State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Ekaterina Khilkova. Internal view of the women’s department of the St. Petersburg drawing school for free-comers (fragment). 1855. State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

Karl Lemokh. High school student (fragment). 1885. State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

The first educational institution for girls was opened during the reign of Catherine II.In 1764, the Empress established the Educational Society for Noble Maidens. It went down in history as the Smolny Institute. The institute existed until 1917.

The subjects of study at the first age (6-9 years) were: the Law of God, Russian and foreign languages (reading and writing), arithmetic, drawing, needlework and dancing. History and geography were added to the second age (9–12 years old) … At the third age (12–15 years old), verbal sciences were introduced, which consisted of reading historical and moralistic books.

This was followed by more: experimental physics, architecture, sculpture, turning art and heraldry. Housekeeping was taught already in practice … The course of the last age (15-18 years) consisted of repeating everything passed, with special attention paid to the Law of God.

Women’s education was significantly different from men’s. Founded back in 1732, the Gentry Land Cadet Corps under Catherine II received a new charter. They studied in the building from the age of five to 21. Young men mastered “useful” sciences (physics, martial arts, tactics, chemistry, artillery), “necessary for the civil rank” (national, state and natural law, moral teaching, state economy), other sciences (logic, mathematics, mechanics, eloquence, geography, history) and “art” (drawing, dancing, fencing, architecture and others).This program was influenced by the ideas of the French Enlightenment.

In 1786, the Charter was adopted for public schools in the Russian Empire. Small schools with two classes of primary education appeared, and in large cities – secondary schools with three classes, as well as main schools with five years of study (the last, fourth grade lasted two years). In the main public schools, they studied arithmetic and geometry, physics and mechanics, natural history and architecture with drawing plans, geography and history, as well as optional Latin and active European languages.Graduates of the main schools could pass the exam for the title of teacher.

In the main public schools, they studied arithmetic and geometry, physics and mechanics, natural history and architecture with drawing plans, geography and history, as well as optional Latin and active European languages.Graduates of the main schools could pass the exam for the title of teacher.

Education in the 19th century

Alexey Korin. Failed again (fragment). 1891. Kaluga Regional Art Museum, Kaluga

Emilia Shanks. New girl at school (fragment). 1892. State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Nikolay Bogdanov-Belsky. Preparation of lessons (fragment). 1900s. Novokuznetsk Art Museum, Novokuznetsk

In 1802, Emperor Alexander I established the Ministry of Public Education.Its main principles were the lack of estates (with the exception of serfs) and free primary education, as well as the continuity of curricula. In 1804, elementary schools were opened at church parishes, where mainly peasant children attended. Since 1803, the main public schools began to be transformed into gymnasiums (the first women’s gymnasium was opened 55 years later, in 1858, in St. Petersburg). Gradually, new subjects were introduced into the program: mythology, statistics, philosophy, psychology, commercial sciences, natural history, foreign languages.In the gymnasiums, emphasis was placed on classical education – the humanities were a priority.

Petersburg). Gradually, new subjects were introduced into the program: mythology, statistics, philosophy, psychology, commercial sciences, natural history, foreign languages.In the gymnasiums, emphasis was placed on classical education – the humanities were a priority.

In 1811, the first admission to the Imperial Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum took place. For six years, boys from noble families were given encyclopedic knowledge. Particular attention was paid to Russian history and the “Russian language”, which was practically not studied in the gymnasiums of that time. Pushkin’s classmate, statesman, historian Modest Korf wrote:

… Until the very end, a general course, semi-gymnasium and semi-university, about everything in the world: mathematics with differentials and integrals, astronomy on a large scale, church history, even higher theology – all this took us as much, sometimes more time than jurisprudence and other political sciences.