How does Joe Ehrmann’s philosophy challenge traditional notions of masculinity. What impact has Ehrmann’s “Building Men for Others” program had on young athletes. How can coaches and mentors apply Ehrmann’s principles to develop character in their teams.

Joe Ehrmann: From NFL Star to Inspirational Coach

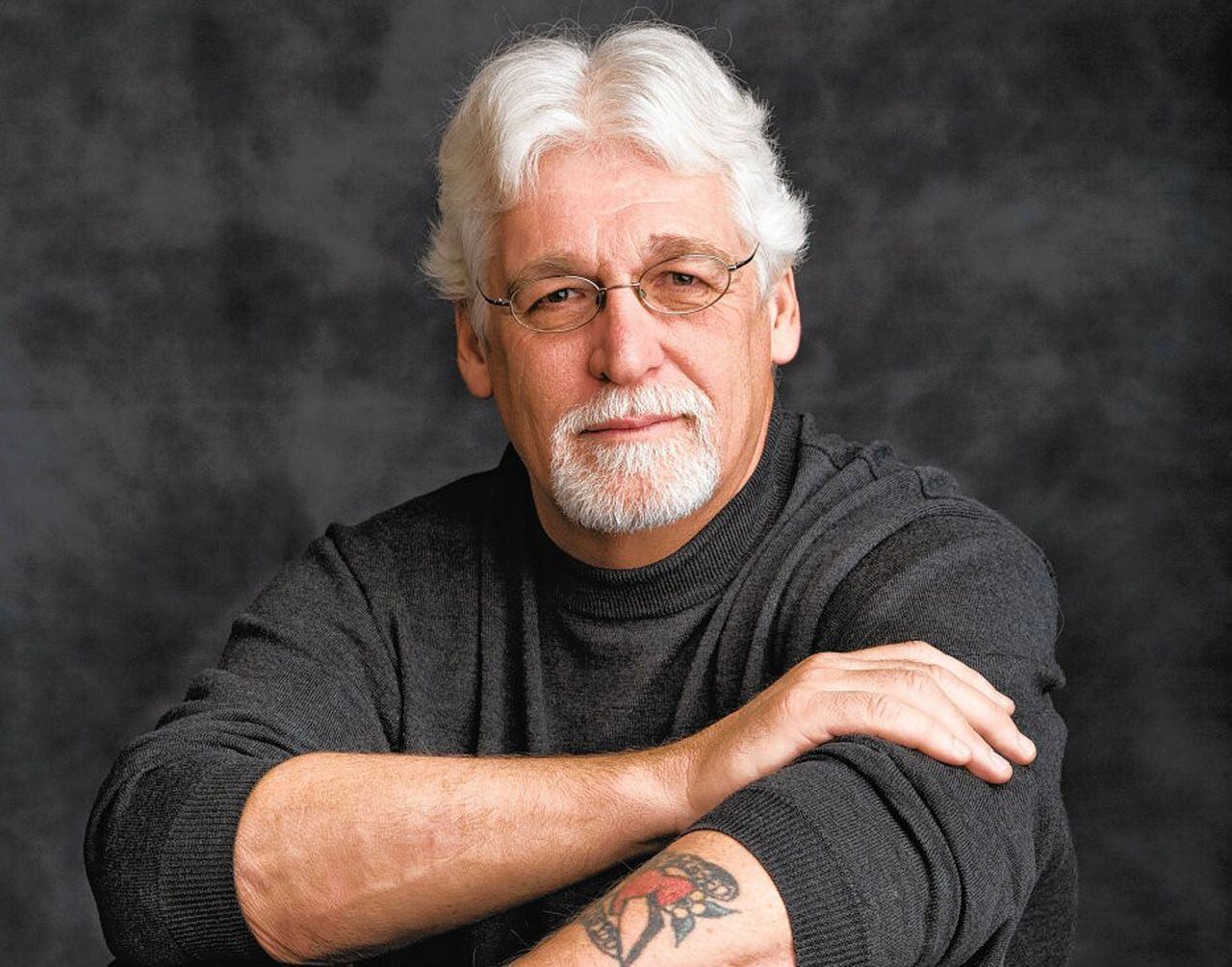

Joe Ehrmann’s journey from NFL All-Pro defensive lineman to influential mentor and coach is a remarkable tale of personal growth and societal impact. After a successful career with the Baltimore Colts in the 1970s, Ehrmann underwent a profound transformation, eventually becoming the Reverend Joe Ehrmann and founding the non-profit organization “Building Men for Others”.

This shift in focus from professional sports to character development represents a significant departure from the typical post-NFL career path. Ehrmann’s transition raises an intriguing question: How can former athletes leverage their experiences to positively influence younger generations?

The Genesis of “Building Men for Others”

Ehrmann’s organization focuses on a crucial aspect of personal development: training men of all ages to develop a healthy view of masculinity centered on the needs of others. This approach challenges traditional notions of manhood often associated with professional sports, such as dominance, aggression, and individual achievement.

The core principles of Ehrmann’s philosophy include:

- Emphasizing empathy and compassion

- Promoting emotional intelligence

- Encouraging community service

- Fostering healthy relationships

- Developing leadership skills rooted in service

The Gilman School Football Program: A Model of Transformative Coaching

One of the most compelling aspects of Ehrmann’s work is his involvement with the Gilman School football team in Maryland. Alongside head coach Francis “Biff” Poggi, Ehrmann has helped implement a unique coaching philosophy that extends far beyond the gridiron.

How does the Gilman School football program differ from traditional high school sports teams? The coaches have created an environment that prioritizes personal growth, community building, and character development alongside athletic achievement. This holistic approach has not only produced championship-winning teams but also young men equipped with valuable life skills.

Key Elements of the Gilman Approach

- Emphasizing team unity across diverse backgrounds

- Promoting self-reflection and personal growth

- Challenging traditional definitions of masculinity

- Encouraging players to consider their impact on others

- Fostering a sense of community and shared purpose

Redefining Masculinity: Ehrmann’s Core Message

At the heart of Joe Ehrmann’s philosophy is a radical redefinition of what it means to be a man in modern society. His approach challenges deeply ingrained notions of masculinity that often prioritize physical strength, emotional stoicism, and individual success above all else.

Instead, Ehrmann promotes a vision of manhood that emphasizes:

- Emotional intelligence and vulnerability

- Empathy and compassion for others

- The ability to form and maintain healthy relationships

- A commitment to serving one’s community

- The courage to stand up for one’s values and beliefs

This redefinition of masculinity raises important questions: How can society better support boys and young men in developing these qualities? What role can sports and other traditionally masculine activities play in fostering a more holistic approach to manhood?

The Impact of “Season of Life” on Readers and Communities

Jeffrey Marx’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book “Season of Life” has brought widespread attention to Joe Ehrmann’s work and philosophy. The book’s impact extends far beyond the world of sports, touching readers from all walks of life who are grappling with questions of purpose, identity, and personal growth.

How has “Season of Life” influenced readers’ perspectives on masculinity and personal development? Many readers report experiencing profound shifts in their understanding of what it means to be a man, a leader, and a positive force in their communities. The book has sparked conversations about the role of sports in character development and the potential for coaches to serve as transformative mentors.

Key Takeaways from “Season of Life”

- The importance of challenging traditional notions of success

- The power of mentorship and positive role models

- The potential for sports to teach valuable life lessons

- The need for a more holistic approach to masculinity

- The transformative impact of focusing on others’ needs

Applying Ehrmann’s Principles Beyond Sports

While Joe Ehrmann’s work has its roots in football coaching, the principles he espouses have far-reaching applications across various fields and aspects of life. How can individuals and organizations in different sectors adapt Ehrmann’s approach to foster personal growth and community engagement?

Business Leadership

In the corporate world, Ehrmann’s emphasis on empathy, emotional intelligence, and service to others aligns with modern leadership theories that prioritize emotional intelligence and servant leadership. Companies that incorporate these principles may see improvements in employee satisfaction, teamwork, and overall organizational performance.

Education

Educators can draw inspiration from Ehrmann’s approach by incorporating character development and community service into their curricula. This holistic approach to education can help students develop not only academic skills but also the emotional and social intelligence necessary for success in life.

Community Organizations

Non-profit organizations and community groups can adopt Ehrmann’s focus on building men (and women) for others by emphasizing volunteer work, mentorship programs, and initiatives that foster a sense of shared responsibility for community well-being.

Challenges and Criticisms of Ehrmann’s Approach

While Joe Ehrmann’s philosophy has garnered significant praise and support, it is not without its critics and challenges. Examining these critiques can provide a more balanced understanding of the approach and its potential limitations.

Potential Criticisms

- Overemphasis on traditionally masculine activities (e.g., football)

- Difficulty in measuring long-term impact

- Potential resistance from those invested in traditional notions of masculinity

- Challenges in scaling the approach to reach a broader audience

- Questions about the applicability of the approach across diverse cultural contexts

How can proponents of Ehrmann’s philosophy address these concerns and continue to refine and improve their approach? Open dialogue, ongoing research, and a willingness to adapt and evolve the program may be key to its continued success and broader adoption.

The Future of “Building Men for Others”

As Joe Ehrmann’s message continues to spread through books like “Season of Life” and his ongoing work with coaches and athletes, what does the future hold for the “Building Men for Others” movement? Several potential developments and areas of growth come to mind:

Expansion into New Areas

While Ehrmann’s work has primarily focused on football and male athletes, there is potential for expansion into other sports and demographics. How might the principles of “Building Men for Others” be adapted to serve female athletes, non-athletes, or individuals in different professional fields?

Integration with Educational Curricula

As awareness of the importance of social-emotional learning grows, there may be opportunities to integrate Ehrmann’s approach more formally into school curricula. This could involve developing specific programs or materials that align with educational standards while promoting character development and community engagement.

Research and Evaluation

To address some of the criticisms and challenges mentioned earlier, there is a need for rigorous research and evaluation of the long-term impacts of Ehrmann’s approach. This could involve longitudinal studies tracking participants over time, as well as comparative analyses with other character development programs.

Global Outreach

While Ehrmann’s work has primarily focused on the United States, there is potential for his message to resonate globally. How might the principles of “Building Men for Others” be adapted to different cultural contexts while maintaining their core essence?

Personal Reflections: The Impact of Joe Ehrmann’s Philosophy

For many readers of “Season of Life” and those who have encountered Joe Ehrmann’s work, the experience can be profoundly transformative. It often prompts deep personal reflection on one’s own understanding of masculinity, success, and purpose in life.

/nginx/o/2024/04/15/16004847t1h1b01.jpg)

Some common areas of personal growth and reflection inspired by Ehrmann’s philosophy include:

- Reevaluating personal definitions of success and achievement

- Examining one’s emotional intelligence and capacity for empathy

- Considering how to better serve and support others in daily life

- Reflecting on the impact of mentors and role models in one’s own life

- Exploring ways to become a more positive influence in one’s community

How can individuals harness these reflections to create meaningful change in their lives and communities? The answer may lie in small, consistent actions that align with Ehrmann’s principles, gradually building towards a more empathetic, service-oriented approach to life.

Practical Steps for Personal Growth

- Engage in regular self-reflection and journaling

- Seek out opportunities for community service and volunteering

- Practice active listening and empathy in daily interactions

- Mentor or support younger individuals in your field or community

- Challenge traditional notions of success and masculinity in conversations with peers

By taking these steps, individuals can begin to embody the principles of “Building Men for Others” in their own lives, creating a ripple effect of positive change in their communities.

The White Rhino Report – “A Marketplace Where Many Diverse Ideas Meet for Coffee!”: Building Men for Others – A Review of “Season of Life”

My friend, David Mann of Spring Mill Venture Partners in Bloomington, Indiana, recently made me aware of a book that is nothing short of life changing. David is a graduate of the Naval Academy and a Renaissance Man, so you can imagine that our conversations often center on issues of leadership and what it means to be a true and broadly educated Renaissance Man in this age of hyper-specialization. In the course of one of our dialogues, David mentioned the book, Season of Life, written by the Pulitzer Prize winning journalist Jeffrey Marx. The full title page spells out what this book is all about and why it is creating such a buzz: Season of Life – a Football Star, a Boy, a Journey to Manhood.

The story begins with Jeffrey Marx as a frizzy-headed young ball boy nicknamed “Brillo” working with the Baltimore Colts. During those years, he built a friendship with Joe Ehrmann, who starred as a defensive lineman with the great Baltimore Colts teams of the 1970’s. Flash forward to 2001. Jeffrey Marx has become a respected journalist who won the Pulitzer Prize for his investigative reporting; NFL All-Pro lineman Joe Ehrmann has morphed into the Rev. Joe Ehrmann, a gentle giant who runs a non-profit organization called: “Building Men for Others.” The organization focuses on training men of all ages to become focused on the needs of others as they develop a healthy view of masculinity.

During those years, he built a friendship with Joe Ehrmann, who starred as a defensive lineman with the great Baltimore Colts teams of the 1970’s. Flash forward to 2001. Jeffrey Marx has become a respected journalist who won the Pulitzer Prize for his investigative reporting; NFL All-Pro lineman Joe Ehrmann has morphed into the Rev. Joe Ehrmann, a gentle giant who runs a non-profit organization called: “Building Men for Others.” The organization focuses on training men of all ages to become focused on the needs of others as they develop a healthy view of masculinity.

When Jeff and Joe met for the first time in eighteen years, their conversation took an interesting turn that provides a good window into the soul of what this book is really about. I’ll share an excerpt:

Joe asked me a question that initially seemed to be strangely out of place in our conversation: Had I read Richard Ben Cramer’s recently published biography of baseball great Joe DiMaggio? I had not. But I had heard about it. I knew it painted a pathetic picture of a much-celebrated public hero. . . who was anything but heroic in his private life.

I knew it painted a pathetic picture of a much-celebrated public hero. . . who was anything but heroic in his private life.

‘Well, more than anything, it’s the story of a man’s search for a heart,’ Joe said. ‘And that’s really a journey that an awful lot of athletes go through, an awful lot of men, period, because we’re searching based on all the wrong things – money, fame, power.’ (pages 29-30)

The book proceeds to recount the relationship that Jeff and Joe built over the next few years, and Jeff’s embarking on writing the story of Joe’s other passion – helping to coach the championship football team from the Gilman School in Maryland. What emerges is a fascinating and deeply moving parallel account of a journalist chronicling a unique and successful approach to coaching high school football players and challenging them to become the kind of men that they should become – while at the same time the journalist looks inward at his own journey towards a healthy understanding of manhood.

Gilman head coach, Francis “Biff” Poggi and defensive coordinator, Joe Ehrmann, and the eight other assistant coaches have created a unique and mind-boggling philosophy that has built a team of perennial champions that is often the top ranked high school team in the State of Maryland. Let’s listen in on part of Coach “Biff’s” opening speech to the team in the opening practice for the 2001 season:

“We’re going to go through this whole thing as a team. We are the Gilman football community. A community. This is the only place probably in your whole life where you’re gonna be together and work together with a group as diverse as this – racially, socially, economically, you name it. It’s a beautiful thing to be together like this. You’ll never find anything like it in the world – simply won’t happen. So enjoy it. Make the most of it. It’s yours” (page 44)

OK. There’s the appetizer. Now run out and get a copy of Season of Life so you can devour the entire smorgasbord of inspirational stories and thought-provoking reflections. Any man who is self-aware enough to ask himself the question: “What does it really mean to be a man?” should read this book. And any woman who wants to support a man who undertakes such a journey should read the book as well.

Any man who is self-aware enough to ask himself the question: “What does it really mean to be a man?” should read this book. And any woman who wants to support a man who undertakes such a journey should read the book as well.

Oh, by the way, after finishing reading Season of Life, I reached for the next book on my special shelf at home that I have mentally labeled “Next Books to Read.” So, I just finished the Richard Ben Cramer biography of Joe DiMaggio mentioned above. The book is very well written and one that I am glad I read. Joe Ehrmann was right; the life of Joe DiMaggio the man stands in marked contradistinction to the “Men for Others” that Ehrmann and his colleagues are trying to build. Joltin’ Joe was a man for himself – and in the end he died a lonely and pathetic figure.

Read both books. The contrast will take your breath away.

As always, I welcome your comments.

The 3 Scariest Words A Boy Can Hear : NPR

Heard on All Things Considered

By

NPR Staff

Joe Ehrmann, shown in 1975, was a defensive lineman with the Baltimore Colts for much of the ’70s. He says that as a child, he was taught that being a man meant dominating people and circumstances — a lesson that served him well on the football field, but less so in real life.

He says that as a child, he was taught that being a man meant dominating people and circumstances — a lesson that served him well on the football field, but less so in real life.

Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated/Getty Images

Joe Ehrmann, shown in 1975, was a defensive lineman with the Baltimore Colts for much of the ’70s. He says that as a child, he was taught that being a man meant dominating people and circumstances — a lesson that served him well on the football field, but less so in real life.

Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated/Getty Images

This story is part of All Things Considered‘s “Men in America” series.

It’s rare that a man makes it through life without being told, at least once, “Be a man.” To Joe Ehrmann, a former NFL defensive lineman and now a pastor, those are the three scariest words that a boy can hear.

Ehrmann — who played with the Baltimore Colts for much of the 1970s and was a lineman at Syracuse University before that — confronted many models of masculinity in his life. But, as with many boys, his first instructor on manhood was his father, who was an amateur boxer.

Use #menpr to join in the conversation about men in America on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram.

Ehrmann says of his father: “I think his definition, which was very old in this country, was: Men don’t need. Men don’t want. Men don’t touch. Men don’t feel. If you’re going to be a man in this world, you better learn how to dominate and control people and circumstances.”

On the football field, those lessons served Ehrmann well. But, as he tells NPR’s Audie Cornish, it was not the same case in the pediatric oncology ward. In 1978, Ehrmann’s teenage brother was diagnosed with cancer. However tough Joe was on the field, he did not feel equipped to help his brother or himself.

In 1978, Ehrmann’s teenage brother was diagnosed with cancer. However tough Joe was on the field, he did not feel equipped to help his brother or himself.

Interview Highlights

On how his brother’s death affected him

When he died, that was devastating to me. And I started to ask all the questions about what is the role, the meaning, the purpose of life. I was 29 years old, I was six years into my NFL career, and I had no concept — no concept what life was about, and no concept what I was about. And on this journey, I ended up asking the question: What does it mean to be a man? …

I recognized that everything I had invested my life in — all my accomplishments, my achievements, the stuff I had accumulated — I recognized at that moment they offered no hope or help to my 19-year-old brother — 18-year-old brother — lying on his deathbed. …

The great myth in America today is that sports builds character. That’s not true in a win-at-all-costs culture. Sports doesn’t build character unless the coach models it, nurtures it and teaches it.

Sports doesn’t build character unless the coach models it, nurtures it and teaches it.

Joe Ehrmann

All I had was these old “man up” kind of things — “suck it up, we’ll get through this together” — when he really needed the emotional, the nurturing, the love. And I had to really struggle to pull that out of my heart.

On the roles a coach can play in his players’ lives

There’s two kinds of coaches in America: You’re either transactional or you’re transformational. Transactional coaches basically use young people for their own identity, their own validation, their own ends. It’s always about them — the team first, players’ needs down the road.

And then you have transformational coaches. They understand the power, the platform, the position they have in the lives of young people, and they’re going to use that to change the arc of every young person’s life. I think football is an ideal place — sports in general — team sports are an ideal place to help boys become men. And the great myth in America today is that sports builds character. That’s not true in a win-at-all-costs culture. Sports doesn’t build character unless the coach models it, nurtures it and teaches it.

And the great myth in America today is that sports builds character. That’s not true in a win-at-all-costs culture. Sports doesn’t build character unless the coach models it, nurtures it and teaches it.

In addition to working as a pastor, Joe Ehrmann volunteers as a coach at Gilman School in Baltimore.

Coach for America

hide caption

toggle caption

Coach for America

On what those philosophies look like on the field

I think there’s a lot of screamers, there’s a lot of shouters, there’s a lot of shamers. My approach is this: Boy, you’re in the middle of the game, and some kid’s having a tough time. They get beat. … I tell all my players, “Come on over to me during the game and I’ll give you a hug.” And you think about the power of a hug versus swearing, shouting, shaming at some kid.

When I played football, I hated [when] some kid would get a knee injury, your teammate would go down and that coach would say move the practice down 20 yards and leave that kid laying there. … As coaches, we can kneel down next to that kid, you affirm the tears, the pain, the emotions, and you bring all the team around to say, “How can we help Bobby? He’s one of us; he’s done so much. He had so many dreams.” So, you teach them how to build authentic community as men caring for and loving each other.

On the changes he’s seen in ideas of masculinity

I think those three lies of masculinity — athletic ability, sexual conquest, economic success — in many ways, those things have been heightened. You have this increase in social media. You have young boys coming into this world, and they are hit 24/7. They’re given all kinds of negative messages about their masculinity. They’ve been conditioned, and they have way more messaging out of this culture than I ever had as a young boy.