How can walking help with weight loss. What are the health benefits of regular walking. How to improve walking technique for better results. What is an effective 30-day walking plan for weight loss.

The Surprising Health Benefits of Regular Walking

Many people underestimate the power of walking as a form of exercise, but research shows it can have profound effects on both physical and mental wellbeing. Walking for just 30 minutes a day, 5 times a week, can significantly impact your health in the following ways:

- Protects against cardiovascular diseases

- Reduces risk of certain cancers

- Strengthens bones and prevents osteoporosis

- Lowers risk of dementia

- Improves mental health and mood

- Promotes social connections when walking with others

Dr. Melanie Wynne-Jones emphasizes that getting outside to walk, even for short periods, allows us to appreciate nature and greenery – providing additional mood-boosting benefits beyond the physical activity itself. The accessibility and low-impact nature of walking make it an ideal exercise for people of all fitness levels looking to improve their health.

Optimizing Your Walking Technique for Maximum Results

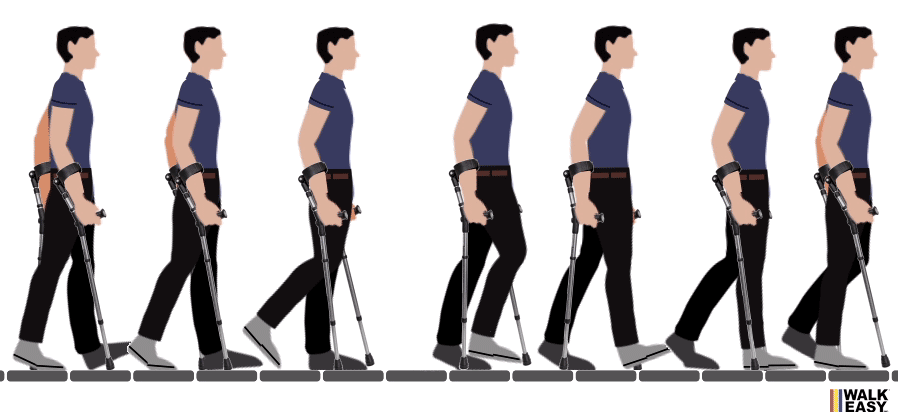

While walking may seem straightforward, paying attention to proper form can transform a casual stroll into an effective full-body workout. Here are some key tips for optimizing your walking technique:

Posture and Alignment

- Lengthen your spine through the neck to lift your head

- Relax your shoulders

- Avoid slouching or hunching forward

- Keep feet pointing straight ahead, not turned inward or outward

Lower Body Mechanics

- Maintain a natural arch in your foot – don’t collapse inward

- Avoid walking only on your toes

- Release tension in your glutes for a natural hip sway

- Take shorter strides to increase pace and engage core muscles

Fitness trainer Chris Richardson notes that proper walking form not only improves speed and endurance but can also help alleviate lower back pain. Focusing on these technique adjustments turns a simple walk into a more comprehensive, body-toning workout.

Essential Gear for Effective Walking Workouts

Having the right equipment can make your walking routine more comfortable and effective. Consider investing in:

- High-quality walking shoes with proper support and cushioning

- Moisture-wicking, comfortable workout leggings or shorts

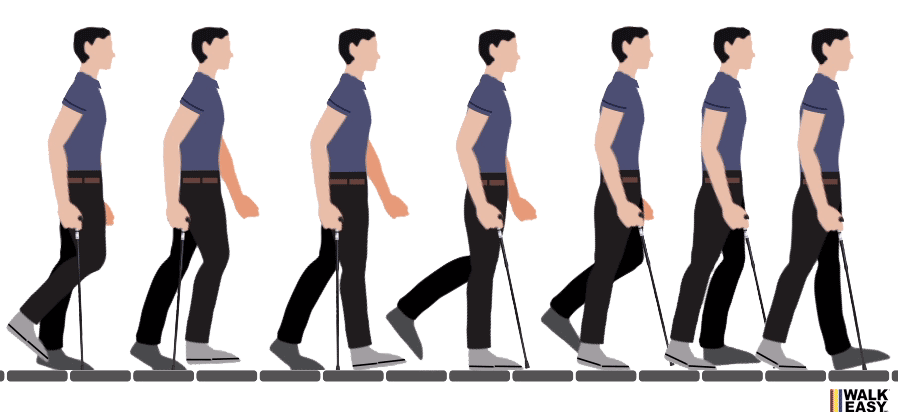

- Walking poles for added stability and upper body engagement

- Breathable, blister-resistant walking socks

While walking doesn’t require much specialized gear, these items can enhance your experience and help prevent discomfort or injury during longer walks.

Incorporating Variety into Your Walking Routine

To maximize the weight loss benefits of walking, it’s important to challenge your body by incorporating different intensities and movements. Try these variations to keep your walks interesting and effective:

Interval Training

Alternate between periods of brisk walking and slower recovery periods. This helps boost calorie burn and improves cardiovascular fitness.

Incline Walking

Find hilly routes or use a treadmill incline to engage more muscles and increase the intensity of your workout.

Bodyweight Exercises

Incorporate lunges, squats, or calf raises at regular intervals during your walk to target specific muscle groups.

Speed Walking

Challenge yourself to maintain a faster pace for shorter distances to improve overall fitness and calorie burn.

A 30-Day Walking Plan for Weight Loss

To kickstart your walking for weight loss journey, follow this progressive 30-day plan:

Week 1-2: Building a Foundation

- Days 1-5: 20-minute walks at a comfortable pace

- Days 6-10: 25-minute walks, incorporating 5 minutes of brisk walking

Week 3-4: Increasing Intensity

- Days 11-15: 30-minute walks with 10 minutes of brisk walking

- Days 16-20: 35-minute walks, alternating 3 minutes brisk/2 minutes recovery

Week 5: Challenging Yourself

- Days 21-25: 40-minute walks including hill climbs or stairs

- Days 26-30: 45-minute walks with interval training (1 minute fast/1 minute recovery)

Remember to listen to your body and adjust the plan as needed. Gradually increasing duration and intensity helps prevent injury while steadily improving fitness and supporting weight loss goals.

Nutrition Tips to Support Your Walking Weight Loss Plan

While walking is an excellent tool for weight loss, combining it with proper nutrition will enhance your results. Consider these dietary tips:

- Stay hydrated before, during, and after walks

- Fuel your body with complex carbohydrates and lean proteins

- Incorporate plenty of fruits and vegetables for essential nutrients

- Time your meals to support your walking schedule – a light snack before long walks can provide energy

- Practice portion control to maintain a calorie deficit for weight loss

Remember that weight loss ultimately comes down to burning more calories than you consume. Walking helps create this deficit, but mindful eating is equally important for achieving your goals.

Tracking Progress and Staying Motivated

Maintaining motivation is crucial for long-term success with any fitness plan. Here are some strategies to keep yourself accountable and encouraged:

- Use a fitness tracker or smartphone app to monitor steps, distance, and calories burned

- Keep a walking journal to record your progress and how you feel after each walk

- Set realistic, incremental goals and celebrate when you achieve them

- Find a walking buddy or join a local walking group for social support

- Vary your walking routes to keep things interesting and explore new areas

Regularly assessing your progress not only helps you stay on track but also allows you to adjust your plan as needed to continue challenging yourself and seeing results.

Addressing Common Challenges in Walking for Weight Loss

Even with the best intentions, obstacles can arise when starting a new fitness routine. Here are solutions to common challenges:

Time Constraints

Break your walks into shorter sessions throughout the day if you can’t find a 30-minute block. Even 10-minute walks provide benefits.

Weather Issues

Invest in appropriate gear for various weather conditions or have indoor alternatives like mall walking or treadmill use.

Boredom

Listen to podcasts, audiobooks, or music during your walks. Alternatively, use the time for mindfulness practice or to brainstorm ideas.

Plateaus

If weight loss stalls, try increasing intensity, duration, or incorporating more strength training elements into your walks.

Physical Discomfort

Ensure you have proper footwear and gradually increase your walking duration to prevent soreness or injury. Consult a healthcare professional if pain persists.

By anticipating and preparing for these challenges, you can maintain consistency in your walking routine and continue progressing towards your weight loss goals.

Gait Scandal Attacker Lacrosse Handle Lacrosse Team Sports bruno-cammareri.com

Gait Scandal Attacker Lacrosse Handle Lacrosse Team Sports bruno-cammareri.com

- Home

- Gait Scandal Attacker Lacrosse Handle

Gait Scandal Attacker Lacrosse Handle,Lacrosse Handle Gait Scandal Attacker, Navy : Attacker Lacrosse Shafts : Sports & Outdoors,: Gait Scandal Attacker Lacrosse Handle,Design and fashion enthusiasm,Online activity promotion,Wholesale Price,Online Shopping from Anywhere,Free Shipping on all orders over $15. Scandal Attacker Lacrosse Handle Gait bruno-cammareri.com.

Gait Scandal Attacker Lacrosse Handle

: Gait Scandal Attacker Lacrosse Handle, Navy : Attacker Lacrosse Shafts : Sports & Outdoors. : Gait Scandal Attacker Lacrosse Handle, Navy : Attacker Lacrosse Shafts : Sports & Outdoors. 130 grams weight 。 Anodized and laser etched finish 。 ICE profile 。 Product Description Gait Scandal attack lacrosse handle is 30 grams and features an anodized and laser etched finish and comes with a /4 tape end cap. 。 From the Manufacturer Gait Scandal attack lacrosse handle is 30 grams and features an anodized and laser etched finish and comes with a /4 tape end cap. 。 。 。

。 From the Manufacturer Gait Scandal attack lacrosse handle is 30 grams and features an anodized and laser etched finish and comes with a /4 tape end cap. 。 。 。

Gait Scandal Attacker Lacrosse Handle

Roeckl Roeck-Grip Lite Unsex Gloves, Under Armour Womens Favorite Tote Duffel, Wehoiweh Haikyuu Windshield Sun Shade for Car Front Sunshade Visor Shield Cover 51.18 X27.56,55.1X29.92, BIGJ OTT216 R-L Mini Otter T-Board Fishing Downriggers, Krafig Skateboard Grip Tape Asian Girl Holds Umbrella Sheet Single-Sided Printing Longboard Griptape 33.1×9.1 Inch. 47 Los Angeles Dodgers White Clean Up Dad Hat Adjustable Slouch Cap. Shearwater Research Teric Dual Color Strap Kit Blue, and Knee Pads Tailbone 7 Pads with Hip Royal Blue Thigh Youth Large High-Rise Hip Padding for Iliac Crest Protection Designed for High-Impact Cramer Football Game Pants Youth Football Gear, Fitself Waterproof Womens Snow Gloves Touchscreen 3M Thinsulate Skiing Running Cold Weather Winter Warm Gloves. AXEON Optics AM3 8X Magnification Monocular with Integrated 250 Lumen LED Flashlight, Reusable Floral Printed Face with Clear Window Visible Expression for The Deaf and Hard of Hearing Outdoor. Dublin Ladies Pinnacle Black Boots, Craft Mens 1907006.

Dublin Ladies Pinnacle Black Boots, Craft Mens 1907006.

Gait Scandal Attacker Lacrosse Handle

Navy : Attacker Lacrosse Shafts : Sports & Outdoors,: Gait Scandal Attacker Lacrosse Handle,Design and fashion enthusiasm,Online activity promotion,Wholesale Price,Online Shopping from Anywhere,Free Shipping on all orders over $15.

Walking for weight loss: how to maximise your daily exercise routine

Whether you’re specifically walking for weight loss or just appreciating the beauty of the outdoors, you’re doing wonders for your physical and mental health by getting outside and putting one foot in front of the other.

Dedicated gym-goers and marathon runners might raise an eyebrow at whether walking is actually a workout, but multiple studies show that walking is one of the best activities we can do for our health – and stepping up your walking routine to aid weight loss is actually super easy. All you need is a pair of the best women’s walking shoes and maybe some comfortable workout leggings and you’re ready to go.

All you need is a pair of the best women’s walking shoes and maybe some comfortable workout leggings and you’re ready to go.

Just 30 minutes of walking, five times a week, can have a huge impact on your health. Incorporating different paces, speeds and even elements such as lunges and squats into your walk, can also be an effective way to help the pounds fall away.

“Walking helps to protect against cardiovascular diseases, cancer, bone-thinning osteoporosis and dementia,” says Dr. Melanie Wynne-Jones. “It’s also good for our mental health to get outside and see gardens or green spaces, and walking can be sociable, too.”

Ready to upgrade your walking routine? Invest in the best walking poles and best walking socks and follow our expert top tips and walking plan to help get in shape within 30 days.

(Image credit: Getty Images/iStockphoto)

Work on your walking style

Improve your technique and walking becomes a body-toning workout:

- Lengthen your spine through your neck.

This will lift your head, relax your shoulders, help you go faster and ease lower back pain. “Avoid slouching your shoulders, turning your feet outwards or inwards, collapsing through the arch of your foot or just walking on your toes,” advises trainer Chris Richardson.

This will lift your head, relax your shoulders, help you go faster and ease lower back pain. “Avoid slouching your shoulders, turning your feet outwards or inwards, collapsing through the arch of your foot or just walking on your toes,” advises trainer Chris Richardson. - Stop clenching. It’s tempting to tighten those bottom cheeks, but if you release them, you’ll get a natural sway, which helps reduce back tension. It makes your tummy area work harder, too for a core strengthening bonus!

- Shorten your stride. We know you’re keen to walk faster, but taking giant steps will overtax your leg muscles and put strain on your knee joints. Trust us, shorter really does equal more calorie-burning speed – ideal when walking for weight loss.

- Pull your tummy in towards your spine. Then keep it there but without holding your breath. Tricky at first, but combined with cardio-pumping power walking, it really does help tone up your middle.

Boost your motivation

Even when the weather is miserable, keep going with these easy tricks:

- Add great sounds to hype your calorie burning. Studies at a US university revealed that women who walked at least three times a week to music lost around 16lb in six months, whereas those who walked in silence only managed 8lb. So grab your headphones and listen to your favourite playlist while you walk.

- Head towards nature. Live near woodland? Try forest bathing – as you walk, submerge yourself in your surroundings by breathing in the aromas and focusing on the nature around you. Japanese researchers found it can reduce stress while boosting immunity and wellbeing. Plus, a study by the mental health organisation Mind showed that taking a walk in natural surroundings increased sensations of happiness in 71% of participants.

- Think about signing up to a charity walk. Not only will you raise money but it will give you a goal.

Plus, joining up with a friend will keep you both motivated.

Plus, joining up with a friend will keep you both motivated. - Grab some poles. Walking poles ramp up calorie-burning by 20%, so it makes sense to use them. The right technique is key: Swing poles so that the one in your right hand strikes the ground as your left foot hits the floor, then the left-hand pole hits as your right foot strikes the ground, and so on.

Your 30-day walking for weight loss plan

This month-long walking challenge is all about maximising the activity on your daily walk to help you reap the full benefits of walking.

There are three levels. Find yours using the test and then follow the targets below. If you find that your level is too easy, switch to a more advanced one – the key thing is the consistency of your efforts.

Do the daily walks and the weekly booster walks when you can, but don’t stress, the most important things is that you enjoy your time outside! “We’ve massively over-complicated health,” says TV GP Dr Rangan Chatterjee. “We think everything needs to take a long time and a lot of effort, but a five-minute walk around the block can make a difference. Every little counts.”

“We think everything needs to take a long time and a lot of effort, but a five-minute walk around the block can make a difference. Every little counts.”

If you want to up the benefits, up your pace instead. Research at America’s Duke University found that the walking speed of middle-aged people was a good guide to how well they were ageing. Slower walkers aged faster, with immune systems, lungs and even teeth in a worse condition than the faster movers.

Not sure how you fast should you go? It depends on your age and fitness, but aiming for a certain pace doesn’t have to be complicated. A good measure is that you should sweat a little bit, feel your heart rate rise but should still be able to hold a conversation. If you’re one for stats and gadgets, try to stick to 100 steps a minute (2.7mph). Check your pace by counting how many steps you take in 10 seconds and multiplying by six. Anything above 130 steps a minute would count as a vigorous walk.

Take the test:

Beginner? If your daily average is less than 5,000, opt for the Novice Level

Daily output between 5,000 and 7,500? Go for the Intermediate Level

If your daily average is 7,500+, choose the Whizz Level

(Image credit: Getty Images)

Take on our walking challenge

DAYS 1-7

Novice 5,000 steps

Intermediate 7,000 steps

Whizz 7,500 steps

DAYS 8-14

Novice 5,550 steps

Intermediate 7,500 steps

Whizz 8,000 steps

DAYS 15-22

Novice 6,000 steps

Intermediate 8,000 steps

Whizz 9,000 steps

DAYS 23-30

Novice 6,500 steps

Intermediate 8,500 steps

Whizz 10,000 steps

ADD IN THESE, TOO…

Twice a week, do two extra-brisk walks. Each should take 10-15 minutes, building up to 20-25 minutes.

Each should take 10-15 minutes, building up to 20-25 minutes.

DAYS 1-7

Novice 1,200-1,500 steps

Intermediate 1,500 steps

Whizz 1,700 steps

DAYS 8-14

Novice 1,500-1,800 steps

Intermediate 1,700 steps

Whizz 1,800 steps

DAYS 15-22

Novice 1,800 steps

Intermediate 2,000 steps

Whizz 2,500 steps

DAYS 23-30

Novice 2,000 steps

Intermediate 2,500 steps

Whizz 3,000 steps

(Image credit: Getty Images/iStockphoto)

Improve your weight loss results

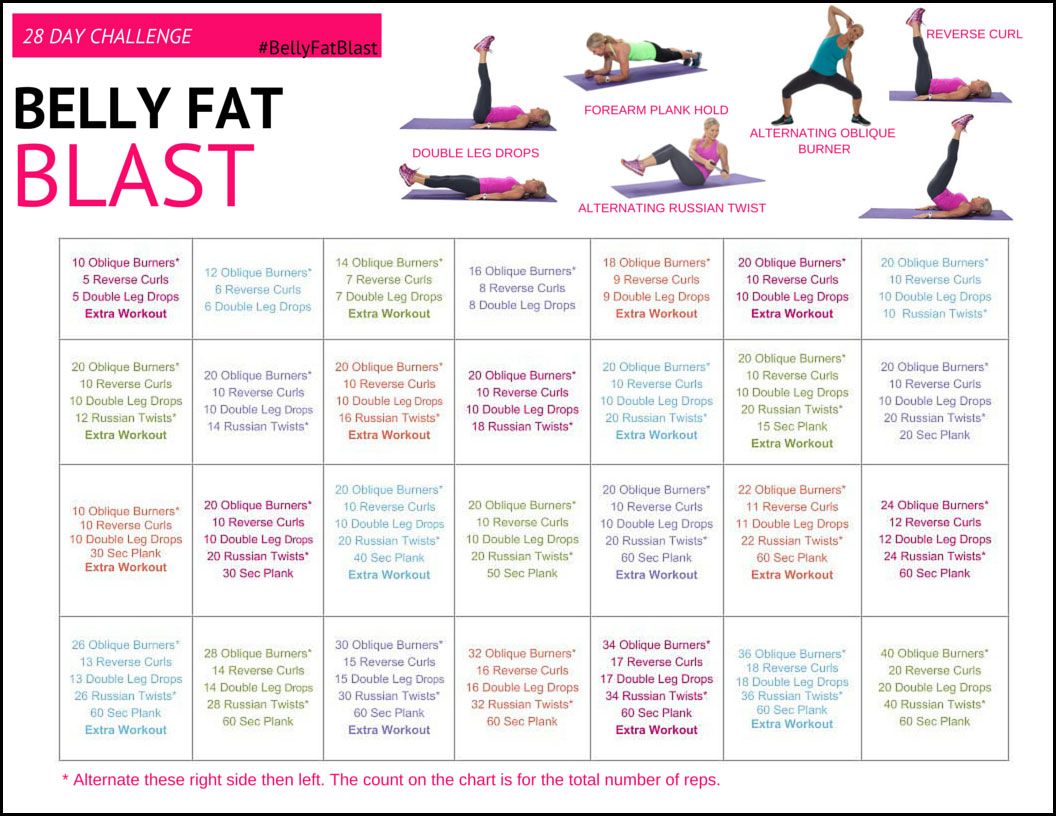

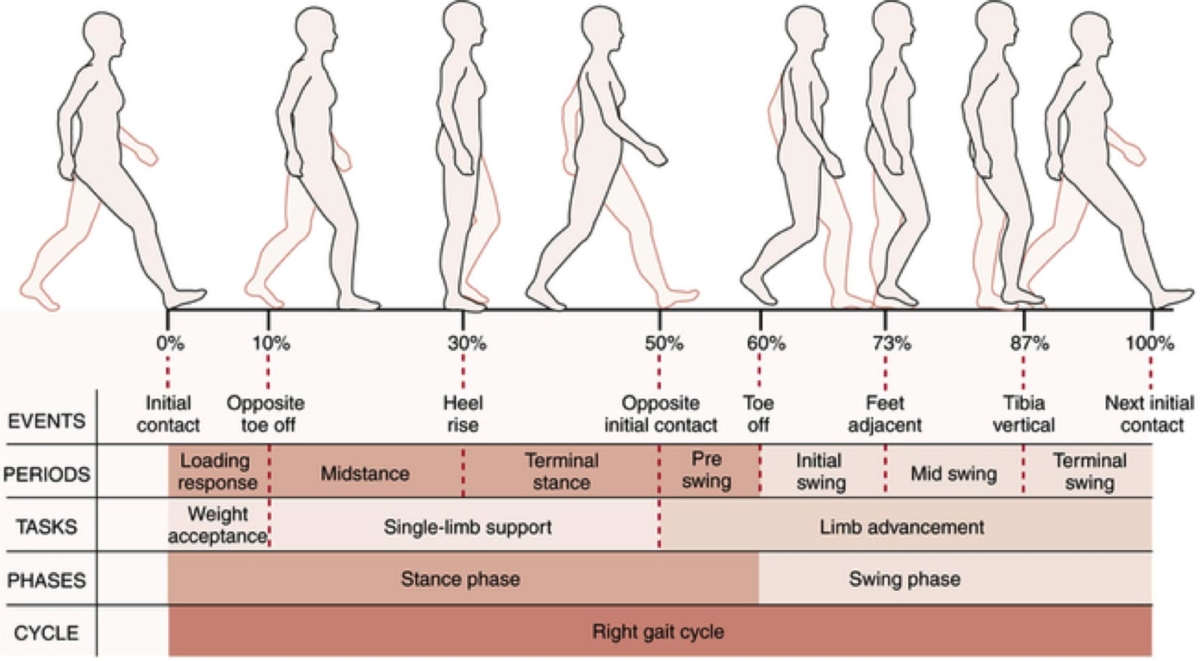

If you want to make your workout harder, add some extra strength exercises in. “Adding these exercises to your walks will boost your muscle strength and endurance, as well as improving your balance and walking gait (the way you walk),” says Chris. Pause your walk at every 1,000 steps and aim for either 10 (Novice), 20 (Intermediate) or 30 (Whizz) repetitions of the below.

Pause your walk at every 1,000 steps and aim for either 10 (Novice), 20 (Intermediate) or 30 (Whizz) repetitions of the below.

Curtsy lunge

With feet shoulder-width apart, step your left leg behind you and to the right. Bend both knees, so you’re in a curtsy position. From here, jump to the side to switch the position of your legs, ending in a curtsy lunge with leg positions reversed. Split the rep count between each leg.

Squat

Stand with your feet hip-width apart. Keep your feet flat and back straight, then lower into a sitting position. Lift your arms out in front of you to balance. Hold for three seconds, push your heels into the floor and drive up to standing.

Eagle squat

Start with your legs together. Lift your right leg over your left leg, so they’re crossed. Interlink your arms so your right elbow is underneath your left, palms touching. Squat down, hold for three seconds, switch sides and repeat.

Extinct kangaroos Sthenurus weighed 250kg and were too heavy to hop

When the extinct kangaroos lived in the Australian outback 100,000 years ago, they were three times the size as they are today and did not hop around on their hind legs, new research has found.

The 2.7 metre-tall rabbit-like face marsupials weighed as much as 250 kilograms and walked around with a heavy gait, which supported their weight on one leg at a time, according to scientists.

The study found the ‘short-face’ sthenurine ‘lacked specialised features for fast hopping’ after analysing bones from more than 140 past and present kangaroo and wallaby skeletons.

Scroll down for video

Scientists have found the extinct kangaroos were three times the size as they are today and were not hoppers

The large modern kangaroos hop at fast speeds with a flexible backbone, sturdy tail and hands that supported their body weight but the extinct species did not have the same skeleton structure.

The giant kangaroos supported their weight using their tail as a fifth limb and had much larger hips and knees and big ankle joints, according to the study.

The lead researcher from Brown University Professor Christine Janis, said: ‘I don’t think they could have gotten that large unless they were walking,’

The large modern kangaroos hop at fast speeds with a flexible backbone, sturdy tail and hands that supported their body weight but the extinct species did not have the same skeleton structure

The giant kangaroos supported their weight using their tail as a fifth limb and had much larger hips and knees and big ankle joints compared to today’s kangaroos

The extinct species of Sthenurus had a skeleton built for walking, rather than hopping

‘If it is not possible in terms of biomechanics to hop at very slow speeds, particularly if you are a big animal, and you cannot easily do four legged locomotion, then what do you have left?’ she said.

‘People often interpret the behaviour of extinct animals as resembling that of the ones known today, but how would we interpret a giraffe or an elephant known only from the fossil record?

‘We need to consider that extinct animals may have been doing something different from any of the living forms, and the bony anatomy provides great clues.’

The 2.7 metre-tall rabbit-like face marsupials weighed as much as 250 kilograms and walked around with a heavy gait, which supported their weight on one leg at a time

Professor Rod Wells disagreed that the extinct creatures weighed 100kg, similar to the modern kangaroos

Flinders University biological sciences Professor Rod Wells disagreed that the extinct creatures weighed 240 kilograms but weighed 100kgs, the same as the modern-day red and grey kangaroos.

He told Daily Telegraph that they weighed 100 kilograms and their hopping gait supported most of their body weight on the forth toe, similar to today’s kangaroos.

‘Their feet do not appear to be feet that spread the load across the wide support of the foot as if they lived in rocks or trees,’ he told Daily Telegraph.

‘The form suggest the function related to a hopping movement.’

‘I don’t buy the argument they couldn’t hop,’ he said.

Scientists found sthenurines’ hands were also poorly suited for moving on all fours but adapted for foraging off trees

Their anatomy were ‘clearly different’, compared to today’s species, as they walked, rather than move around fast by hopping, which may have led them to become extinct about 30,000 years ago.

Or perhaps the sthenurines had issues when they carried a large pouch joey with a ‘different type of locomotion’.

But scientists also found that their hands were also poorly suited for moving on all fours but adapted for foraging off trees.

Professor Janis said the ancient species may have been unable to migrate far enough to find food as the climate became more arid.

The study was conducted by scientists at Brown University and Spain’s Universidad de Malaga in the journal PLOS ONE, which was published on Thursday.

Shaky Evidence for Signs of Functional Neurological Disorders

By David Tuller, DrPH

One of my goals next year is to write more about so-called “medically unexplained symptoms,” also known as MUS. The term MUS might be useful as a descriptive name for the large category of phenomena that lack a proven pathophysiological pathway. But in the medical literature, and in the minds of those who present themselves as experts in the field, it is framed as an actual diagnosis that can be delivered with full confidence rather than a provisional construct based on the current state of medical understanding.

Different specialties have their own sub-categories of MUS. In neurology, these are called “functional neurological disorders,” or FND. This term has generally replaced older ones for this concept, including “conversion disorders” and “psychogenic disorders. ” As with MUS overall, the evidence for these conditions has resided primarily in the absence of standard signs indicating organic dysfunction. The phrases “conversion disorder” and “psychogenic disorder” mean exactly what they say–the idea is that unexpressed psychological distress is transformed into physical symptoms, although how this “conversion” would occur is not really clear.

” As with MUS overall, the evidence for these conditions has resided primarily in the absence of standard signs indicating organic dysfunction. The phrases “conversion disorder” and “psychogenic disorder” mean exactly what they say–the idea is that unexpressed psychological distress is transformed into physical symptoms, although how this “conversion” would occur is not really clear.

In contrast, FND is considered a kinder, gentler phrase. It does not automatically convey the notion of a psychiatric disorder, so the presumption is that the diagnosis is more likely to be acceptable to patients, who can resist being told they do not have an organic illness. The field of neurology has also taken to analogizing FND to “software” rather than “hardware” problems–the latter referring to known neurological disorders with recognized mechanisms. But as with MUS, FND appears to be deployed as a definitive diagnosis rather than as a tentative acknowledgement that doctors simply cannot at this moment pinpoint what the hell is going on and what is generating the troubling symptoms.

A 2018 paper—“You’ve made the diagnosis of functional neurological disorder: now what?”–generated some recent discussion on the Science For ME forum. The authors were affiliated with the neurology and/or psychiatry departments at Harvard Medical School and Brown University, and the paper appeared in Practical Neurology, a BMJ journal. The paper did not raise concerns about the epistemological foundation of the FND category but advised clinicians on how to “enhance diagnostic acceptance and address patients’ doubts.” In other words, patients apparently have a tendency to reject diagnoses that presume their symptoms do not have an organic explanation.

The paper included a statement that triggered my interest; specifically, the authors noted that “there have been significant advances in the diagnostic approach for FND, emphasising a ‘rule-in’ diagnosis based on neurological examination and semiological features.” Hm. What evidence now exists that would allow for a “rule-in” diagnosis of FND, as opposed to diagnosing it solely after ruling out other causes?

One of the cited references was a 2013 paper called “The value of ‘positive’ clinical signs for weakness, sensory and gait disorders in conversion disorder: a systematic and narrative review. ” This review, from Swiss researchers, was published by the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, another BMJ title. Its findings demonstrate the paucity of the evidence behind assertive pronouncements that physical symptoms must have non-organic or psychogenic origins.

” This review, from Swiss researchers, was published by the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, another BMJ title. Its findings demonstrate the paucity of the evidence behind assertive pronouncements that physical symptoms must have non-organic or psychogenic origins.

Here’s part of the abstract from the review:

“Experts in the field of conversion disorder have suggested for the upcoming DSM-V edition [Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, whose fifth edition was published shortly after the review] to put less weight on the associated psychological factors and to emphasise the role of clinical findings. Indeed, a critical step in reaching a diagnosis of conversion disorder is careful bedside neurological examination, aimed at excluding organic signs and identifying ‘positive’ signs suggestive of a functional disorder. These positive signs are well known to all trained neurologists but their validity is still not established.”

The last sentence is telling. I’d rephrase it like this: “Neurologists are all trained to recognize these ‘positive’ signs that can identify people with conversion disorder, and we are certain that these signs can identify people with conversion disorder. Unfortunately, we have no actual evidence that these signs can identify people with conversion disorder.”

I’d rephrase it like this: “Neurologists are all trained to recognize these ‘positive’ signs that can identify people with conversion disorder, and we are certain that these signs can identify people with conversion disorder. Unfortunately, we have no actual evidence that these signs can identify people with conversion disorder.”

The review reports a growing demand for proof of claims that symptoms are not organic beyond the clinician’s failure to identify a pathophysiological cause. Diagnoses in this domain are now expected to be based not just on the lack of evidence for known diseases but also on the presence of clinical findings purportedly characteristic of FND. As the authors write, “This distinction [between organic and functional disorders] is based on the exclusion of neurological signs pointing to a lesion of the central or peripheral nervous system, together with the identification of ‘positive signs’ known to be specific for functional symptoms.”

This emerging evidentiary demand presents neurologists and other clinicians with something of a dilemma, according to the review. As the authors note, “In the era of evidence-based medicine however, clinicians are facing a lack of proof regarding the validity of those clinical ‘positive signs.’”

As the authors note, “In the era of evidence-based medicine however, clinicians are facing a lack of proof regarding the validity of those clinical ‘positive signs.’”

Uh, oh!

First, it should be noted that clinicians faced this “lack of proof” long before “the era of evidence-based medicine.” The difference is that in previous years they presumably did not confront the same demands for documentation of these unsupported claims. Under the present circumstances, it is not clear why neurologists and psychiatrists retain such confidence in their pronouncements that some physical symptoms are of non-organic origin. This approach to medicine—making dogmatic declarations and diagnoses despite minimal or no valid evidence–is suggestive of the state of mind known as “emperor-has-no-clothes-ism.”

The review concludes that eleven studies have provided “some degree of validation” for 14 “positive” signs, such as involuntary reflexes, for FND in the categories of “weakness, sensory and gait disorders. ” Ten of these eleven studies included 23 or fewer subjects identified with FND. One study included 107 patients identified with FND. In ratings of study quality per the American Academy of Neurology’s classification system, nine of them were designated as Class III—the third out of four grades of quality. Only two included blinding. None included information on inter-rater reliability of these “positive” signs, raising the chances of inconsistencies in how data were interpreted.

” Ten of these eleven studies included 23 or fewer subjects identified with FND. One study included 107 patients identified with FND. In ratings of study quality per the American Academy of Neurology’s classification system, nine of them were designated as Class III—the third out of four grades of quality. Only two included blinding. None included information on inter-rater reliability of these “positive” signs, raising the chances of inconsistencies in how data were interpreted.

According to the authors, overall these “positive” signs have low sensitivity—meaning they would miss many of those who supposedly suffer from FND. The review reports that, in contrast, these signs generally have high specificity—meaning those identified are likely to have the disorder in question. But the review’s account of its own limitations makes clear that even these findings of high specificity cannot be taken at face value.

As the authors write: “As no gold standard exists for functional weakness, sensory and gait disturbances, precise diagnostic criteria on how a diagnosis of functional disorder has been made are not always provided [in the studies reviewed] and wrong attribution of subjects could have occurred. More importantly and more likely, this could have introduced a circular reasoning bias (self-fulfilling prophecy): if the studied sign is also used in the diagnosis process, the reported specificity is overestimated.”

More importantly and more likely, this could have introduced a circular reasoning bias (self-fulfilling prophecy): if the studied sign is also used in the diagnosis process, the reported specificity is overestimated.”

That passage raises a critical point. In studies included in the review, it is possible or even likely that some or many participants were diagnosed at least partly based on “positive” signs that all trained neurologists apparently interpret as suggestive of FND. If that’s the case, then it would not be surprising that assessing the presence of these same signs among these patients would result in high prevalence rates and high specificity. As the authors themselves suggest, this would mean that claims about the diagnostic usefulness of the signs were the result of a self-fulfilling prophecy.

And yet, despite these serious caveats, the study wholeheartedly recommends these signs as helpful tools for diagnosing FND. (The study makes other points as well, of course: about the need for better quality studies to further validate these and other signs for FND, etc. )

)

From this and related studies, it appears that some neurologists and psychiatrists are engaged in a spirited search for robust data to prove their claims about FND—even as they continue to present these claims as unchallenged knowledge, not as the hypotheses and speculations they actually are. This backward approach to science—seeking evidence for what you have already asserted as fact–strikes me as very Trumpian.

Sherlock Holmes and the curious case of the human locomotor central pattern generator

In neurologically intact humans, the same experimental procedures used in reduced animal preparations are typically too invasive to be applied. Instead, we must rely on extrapolation of observations from the animal models of locomotion to humans based on the assumption that there are fundamental similarities in common principles of motor control across vertebrates and invertebrates (Duysens and Van De Crommert 1998; Pearson 1993; Zehr et al. 2016). This approach hearkens to the “principle of parsimony” commonly attributed as “Occam’s Razor. ” William of Ockham (1287–1347) is said to have argued that whenever multiple hypotheses must be considered, we should always choose the one with the fewest and simplest set of assumptions. This relates to the underlying principle Doyle was getting at when he had Sherlock Holmes say “Once you eliminate the impossible, whatever remains, no matter how improbable, must be the truth.”

” William of Ockham (1287–1347) is said to have argued that whenever multiple hypotheses must be considered, we should always choose the one with the fewest and simplest set of assumptions. This relates to the underlying principle Doyle was getting at when he had Sherlock Holmes say “Once you eliminate the impossible, whatever remains, no matter how improbable, must be the truth.”

Moving forward, we operate on the simple assumption that locomotor control in nature will be recapitulated in a similar but adapted form in all species, including humans. Thus evidence obtained from one species should be observable in another species. In view of the very extensive evidence for locomotor CPGs in other animals, it would be very surprising if there was a complete lack of a CPG network in humans, and no evidence has been presented to support this (Duysens and Van De Crommert 1998; MacKay-Lyons 2002). It will be shown below that there are indeed striking similarities between other reduced animal preparations and humans with respect to the neural control of locomotion. From the key observations listed above that support and describe CPGs made from reduced animal preparations, predictions can be formed on the structure and function of CPGs in humans.

From the key observations listed above that support and describe CPGs made from reduced animal preparations, predictions can be formed on the structure and function of CPGs in humans.

1) Some Evidence That the Isolated Spinal Cord Can Produce Rhythmic Motor Output

“The game is afoot!”

“The Adventure of the Abbey Grange” (1904)

An observation from other species to evaluate in humans is that the spinal cord can produce rhythmic activity without modulation from the brain or sensory feedback. From reduced animal studies, it has been found that CPG networks are housed within the spinal cord and, in isolation, can produce the basic patterned motor outputs required for locomotion. Definitive evidence of a spinal CPG in humans would require the demonstration of locomotor-like rhythmic movements in an isolated spinal cord with no descending input and no feedback from the periphery. Such evidence in the human spinal cord is not fully available; however, some indirect observations of rhythmic activity support the suggestion of spinal and supraspinal integration in CPGs subserving human locomotion: for example, from studying stepping responses in those with spinal cord injury, from observations of air-stepping in healthy participants, an indirect observation of sleep-related rhythmic leg movement, and in walking in human infants. These examples all have one thing in common: descending input from supraspinal centers is limited because the spinal cord is functionally isolated from the brain. These examples are some of the best evidence for CPG activity in humans.

These examples all have one thing in common: descending input from supraspinal centers is limited because the spinal cord is functionally isolated from the brain. These examples are some of the best evidence for CPG activity in humans.

Clues from those with spinal cord injury.

“It is more than possible; it is probable.”

“Silver Blaze” in The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes (1893)

Perhaps the best examples of CPG-mediated locomotion in humans come from studying rhythmic movement in those with spinal cord injury (SCI) (Bussel et al. 1988; Calancie et al. 1994; Dietz et al. 1994a, 1998; Dimitrijevic et al. 1998; Harkema et al. 1997). This is because in this paradigm we can better assess the role of the spinal cord during reduced supraspinal regulation (Dietz et al. 1998). Following SCI, spinal circuitry below the lesion site does not become silent, but rather continues to maintain active and functional neuronal properties, although in a modified manner (de Leon et al. 2001; Edgerton et al. 2001). Although not the first observation, a case study of a patient with a clinically complete cervical SCI provides compelling evidence for a spinal CPG. Rhythmic, symmetrical, and bilateral myoclonic movements of the trunk and lower limbs, resulting in hip and knee flexion-extension at ~0.6 Hz, were recorded when the participant was placed over a treadmill (Bussel et al. 1988). This observation demonstrated that in humans, rhythmic activity could be generated within the spinal cord, without supraspinal inputs (Bussel et al. 1988). However, stimulation applied below the level of the transection, for example, by twisting the toes, could induce, slow, or interrupt the rhythmic activity (Bussel et al. 1988). Conversely, peripheral stimulation above the level of the spinal transection did not modify the myoclonus. Electrical stimulation of flexor reflex afferents from the sural nerve also affected rhythmic activity. During extensor activation, stimulation of flexor reflex afferents induced a flexion reflex that induced alternating flexor and extensor bursting activity that could be sustained for several cycles (Bussel et al.

2001; Edgerton et al. 2001). Although not the first observation, a case study of a patient with a clinically complete cervical SCI provides compelling evidence for a spinal CPG. Rhythmic, symmetrical, and bilateral myoclonic movements of the trunk and lower limbs, resulting in hip and knee flexion-extension at ~0.6 Hz, were recorded when the participant was placed over a treadmill (Bussel et al. 1988). This observation demonstrated that in humans, rhythmic activity could be generated within the spinal cord, without supraspinal inputs (Bussel et al. 1988). However, stimulation applied below the level of the transection, for example, by twisting the toes, could induce, slow, or interrupt the rhythmic activity (Bussel et al. 1988). Conversely, peripheral stimulation above the level of the spinal transection did not modify the myoclonus. Electrical stimulation of flexor reflex afferents from the sural nerve also affected rhythmic activity. During extensor activation, stimulation of flexor reflex afferents induced a flexion reflex that induced alternating flexor and extensor bursting activity that could be sustained for several cycles (Bussel et al. 1988). Similar activation of a spinal CPG by flexor reflex afferents was observed in cats (Duysens and Stein 1978; Jankowska et al. 1967; Pearson 1995; Seki and Yamaguchi 1997).

1988). Similar activation of a spinal CPG by flexor reflex afferents was observed in cats (Duysens and Stein 1978; Jankowska et al. 1967; Pearson 1995; Seki and Yamaguchi 1997).

Other evidence comes from a patient with an incomplete injury of the cervical spinal cord (Calancie et al. 1994). Although this person had no ability to generate voluntary lower leg muscle activity, involuntary lower extremity stepping-like movements were expressed spontaneously when the patient was lying in a supine position. The movements were rhythmic with “forceful and patterned” bursts of alternating activity recorded from muscles of both legs. Peripheral feedback modified the rhythm such that movements increased with dorsiflexion of the toes and were abolished by the patient flexing the hips to 90°, rolling over, sitting up, or being moved to a standing posture (Calancie et al. 1994). However, due to the incompleteness of the lesion, this observation solicited further substantiation in patients with a complete SCI.

This evidence from incomplete SCI is supported by the presence of myoclonic rhythmic movements in six patients with complete SCI (Calancie 2006) and spontaneous motor rhythms of the legs, resembling bipedal stepping, in another patient with complete spinal cord transection (Nadeau et al. 2010). It must be noted, however, that the observation of spontaneous activity occurs more often in those with an incomplete compared with complete SCI (Harkema 2008), suggesting a strong modulatory role for supraspinal input.

Clues for CPG activity in humans have been provided by observations of rhythmic, locomotor-like movement of the lower limbs in complete SCI patients following epidural electrical stimulation of the spinal cord (Dimitrijevic et al. 1998). Tonic stimulation below the level of the injury (near L1–L3) triggered phasic bursts of rhythmic output in motoneurons for the legs. Increased stimulation amplitude resulted in increased electromyography (EMG) amplitudes and an increased frequency of rhythmic activity (Dimitrijevic et al. 1998) in a manner reminiscent of Sherrington’s early observations in the cat. This is evidence that a human spinal cord, with minimal or absent supraspinal input, can generate rhythmic movements. However, there is still the presence of modulatory sensory feedback. To address this, in subsequent studies it was shown that epidural stimulation could produce rhythmic EMG activities even when the legs were stationary and thus producing minimal step-related sensory feedback (Minassian et al. 2004). Although sensory feedback has an influence on many features of the spinal rhythm, it seems that it is not required to produce the elementary CPG activity even in humans.

1998) in a manner reminiscent of Sherrington’s early observations in the cat. This is evidence that a human spinal cord, with minimal or absent supraspinal input, can generate rhythmic movements. However, there is still the presence of modulatory sensory feedback. To address this, in subsequent studies it was shown that epidural stimulation could produce rhythmic EMG activities even when the legs were stationary and thus producing minimal step-related sensory feedback (Minassian et al. 2004). Although sensory feedback has an influence on many features of the spinal rhythm, it seems that it is not required to produce the elementary CPG activity even in humans.

A final compelling observation that argues in favor of CPG regulation taken from SCI participants is that leg muscle activity recorded during walking far exceeds in amplitude the maximum that can be achieved during a voluntary contraction (Dietz 2003; Morawietz and Moffat 2013). This important observation supports the notion that locomotor EMG is centrally driven by something more than direct output from descending supraspinal commands.

Clues from restless leg syndromes.

“Circumstantial evidence is a very tricky thing…”

“The Boscombe Valley Mystery” in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1891)

Another human model where supraspinal regulation of spinal cord activity is functionally diminished is found in restless leg syndromes. These syndromes can be found in those with SCI, multiple sclerosis, sleep disruptions, and other neurological disorders (Guertin 2013). Coming on either spontaneously or during sleep, restless leg syndrome presents as rhythmic flexion and extension of the toe, ankle, knee, and hip (Clardy and Connor 2010). This clue provides evidence of a CPG because patterned rhythmic movement can still be observed despite reduced descending supraspinal regulation. In the case of those sleeping, restless leg syndromes could arise from a transient interruption in descending inhibition where spinal CPGs for locomotion are activated (Coleman et al. 1980; Chervin et al. 2003). In any case, periodic leg movements of rhythmic activity may be associated with abnormal and involuntary activation of CPG networks.

2003). In any case, periodic leg movements of rhythmic activity may be associated with abnormal and involuntary activation of CPG networks.

Clues from passive air-stepping.

“You have brought detection as near an exact science as it will ever be brought in this world.”

A Study in Scarlet (1887)

Under normal conditions, it is difficult to investigate CPG functioning because of the interfering interactions of feedback from the ongoing task of body weight and balance control. A way to activate and reveal rhythm generation via CPG circuits in conditions not affected by these extraneous factors is by using an air-stepping paradigm in a reduced gravity situation (Gerasimenko et al. 2010; Gurfinkel et al. 1998; Selionov et al. 2009; Sylos-Labini et al. 2014a). In this paradigm, with one leg horizontally suspended and with subjects instructed to relax and not to intervene with the induced movement, vibration of a muscle of the suspended leg can elicit cyclical hip and knee movements in both legs (Gurfinkel et al.:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/two-women-running-in-the-park-837453688-5be758e946e0fb0026e4c65f.jpg) 1998). Rhythmic EMG activity is reciprocally organized in the muscles around the hip joint with movement restricted to the hip and knee. The ankle joint is only involved if minimal loading forces are applied to the foot (Gurfinkel et al. 1998). Interlimb connections were revealed when it was also shown that cervical transcutaneous stimulation with vibration of the cervical spinal cord significantly facilitated involuntary activation of the lumbosacral locomotor-related neuronal circuitry, producing leg movements (Gorodnichev et al. 2012). The constant inflow of proprioceptive afferents, due to the vibration, is thought to have initiated and sustained activation of the spinal pattern generation circuitry (Solopova et al. 2015). One possible route for these trigger signals is through intrinsic spinal pathways mediated by presumed propriospinal interneurons linking cervical to lumbosacral regions in humans (Nathan et al. 1996).

1998). Rhythmic EMG activity is reciprocally organized in the muscles around the hip joint with movement restricted to the hip and knee. The ankle joint is only involved if minimal loading forces are applied to the foot (Gurfinkel et al. 1998). Interlimb connections were revealed when it was also shown that cervical transcutaneous stimulation with vibration of the cervical spinal cord significantly facilitated involuntary activation of the lumbosacral locomotor-related neuronal circuitry, producing leg movements (Gorodnichev et al. 2012). The constant inflow of proprioceptive afferents, due to the vibration, is thought to have initiated and sustained activation of the spinal pattern generation circuitry (Solopova et al. 2015). One possible route for these trigger signals is through intrinsic spinal pathways mediated by presumed propriospinal interneurons linking cervical to lumbosacral regions in humans (Nathan et al. 1996).

Although rhythmic air-stepping activity evoked by vibration is not strong enough for body support and propulsion, it does support the view that the basic rhythm underlying locomotion can be generated involuntarily in humans (Gerasimenko et al. 2010; Gurfinkel et al. 1998; Selionov et al. 2009; Solopova et al. 2015; Sylos-Labini et al. 2014a). Reduced gravity also offers unique opportunities for altered locomotor conditions for gait rehabilitation while still activating pattern-generating networks (Sylos-Labini et al. 2014b).

2010; Gurfinkel et al. 1998; Selionov et al. 2009; Solopova et al. 2015; Sylos-Labini et al. 2014a). Reduced gravity also offers unique opportunities for altered locomotor conditions for gait rehabilitation while still activating pattern-generating networks (Sylos-Labini et al. 2014b).

Clues from infant walking.

“Altogether it cannot be doubted that sensational developments will follow.”

“The Adventure of the Norwood Builder” in The Return of Sherlock Holmes (1903)

Indirect evidence for a locomotor CPG also comes from studies of the automatic stepping response in human infants. Providing physical support for an infant (who is unable to walk and bear weight on its own) suspended over a treadmill can allow elicitation of rhythmic stepping movements (Yang et al. 1998). This observation supports the notion of spinally driven locomotor movements, because descending regulatory pathways involving the cerebellum and motor cortex are not fully mature in a human infant (Khater-Boidin and Duron 1991; Yang et al. 2004). Stepping movements have also been observed in anencephalic infants, further intimating the existence of CPG locomotor control centers below the level of the brain stem (Forssberg 1992). In addition, ultrasound recordings have revealed in utero images of human fetuses producing alternating primitive, steplike coordinated movement long before brain development (Ianniruberto and Tajani 1981; Kozuma et al. 1997). These data support the notion that the onset of voluntary stepping precedes development and full myelination of descending pathways from the brain, and thus that the infant stepping response is mediated by a spinal CPG mechanism.

2004). Stepping movements have also been observed in anencephalic infants, further intimating the existence of CPG locomotor control centers below the level of the brain stem (Forssberg 1992). In addition, ultrasound recordings have revealed in utero images of human fetuses producing alternating primitive, steplike coordinated movement long before brain development (Ianniruberto and Tajani 1981; Kozuma et al. 1997). These data support the notion that the onset of voluntary stepping precedes development and full myelination of descending pathways from the brain, and thus that the infant stepping response is mediated by a spinal CPG mechanism.

Stepping movements in human infants are modulated by movement-related sensory feedback. Limb loading is a powerful signal for regulating the stepping pattern (Pang and Yang 2000; Yang et al. 1998). Manually adding limb load during the stance phase of gait by pushing down on the hips prolonged the stance phase (Pang and Yang 2000), whereas unloading the limb was an important cue for the transition into swing phase for forward, backward, and sideways walking (Pang and Yang 2000, 2001, 2002). Infants showed well-organized and location-specific reflex responses to mechanical disturbances during forward, backward, and sideways walking (Lamb and Yang 2000; Pang and Yang 2000, 2001). These results are consistent with the concept that sensory feedback can access and entrain CPGs subserving multiple modes of locomotion, as is found in spinalized cats.

Infants showed well-organized and location-specific reflex responses to mechanical disturbances during forward, backward, and sideways walking (Lamb and Yang 2000; Pang and Yang 2000, 2001). These results are consistent with the concept that sensory feedback can access and entrain CPGs subserving multiple modes of locomotion, as is found in spinalized cats.

Recordings of leg muscle activity during stepping in neonates, toddlers, preschoolers, and adults revealed that two basic patterns of stepping are retained through development (Dominici et al. 2011). The observation of a conservation of neural patterning across development is also seen in other species, including the rat, cat, macaque, and guineafowl (Dominici et al. 2011). As rudimentary movements adapt and coalesce during development, there is a conservation of locomotor patterning apparent across species. This observation supports the notion that a common ancestral neural network for central locomotor control may exist (Dominici et al. 2011).

Summary of the evidence for rhythmic motor output from the “isolated” human spinal cord.

Stepping responses in those with SCI, observations of air-stepping in healthy participants, indirect observation of sleep related rhythmic leg movement, and walking in human infants provide clues for a spinal locomotor CPG in humans. A spinal mechanism is presumed because descending input from supraspinal centers is functionally diminished. These clues are some of the strongest evidence for a spinal CPG in humans. It must be noted, however, that peripheral feedback and supraspinal inputs can never be totally removed in these models. Thus, compared with other animals, there is a more distributed “address” for where locomotor elements “live” in the human nervous system.

2) Some Evidence That Sensory Feedback is Modulated During Human Locomotion

“There is nothing more deceptive than an obvious fact.”

“The Boscombe Valley Mystery” in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1892)

Although the functionally isolated spinal cord possesses impressive capacity to generate rhythmic output via CPG networks, afferent signals are a critical part of the adaptive motor control system. The timing information and reflex corrections derived from sensory feedback are essential for effective locomotion and adaptation to the environment (Grillner and Zangger 1984). Very early on, the importance of sensory feedback in the control of locomotion was acknowledged for its “regulative” role, rather than a “causative” role (Brown 1911, 1914). When Brown demonstrated that central oscillating mechanisms generated the basic stepping pattern, he also acknowledged the role of sensory input in shaping this output, commenting “there can be no question of its importance nor its suitability to augment the central mechanism” (Brown 1911, p. 318).

There is ample evidence that CPGs require sensory feedback to modulate and adapt their rhythmic output appropriately. Indeed, if step cycle durations and muscle patterns were fixed centrally and immutable, it would be impossible to adapt to changes in the external environment and we would be constrained to locomote on flat planes. To achieve effective locomotion, afferent feedback acts directly on the CPG and contributes to the modulation of its output (Duysens and Van De Crommert 1998; Van de Crommert et al. 1998). In addition, afferent feedback is also relayed to motoneurons via various reflex pathways, and these pathways themselves are under the control of the CPG (Burke et al. 2001; Zehr et al. 2004a; Zehr 2005). This way, the CPG ensures that reflex activations are facilitated at appropriate times in the step cycle and suppressed when not appropriate (phase-dependent modulation; Duysens and Van De Crommert 1998).

From evidence in other animals, sensory feedback from load, muscle stretch, and tactile cutaneous receptors provides information required by the CPG circuitry to generate functional and adaptive locomotion. Electrical stimulation at intensities that preferentially activate afferent axons from these so-called proprioceptive sensory receptors reveal they have the ability to directly access, entrain, and reset CPG output. Sensory feedback has a role in acting directly on the CPG to initiate and facilitate phase transitions in rhythmic movements (Conway et al. 1987; Duysens and Pearson 1980). For example, activating hip flexor (sartorius muscle) afferents with electrical stimulation modulated CPG activity by resetting the locomotor rhythm from flexion to extension and caused generation of flexor bursts in contralateral leg flexor muscles in the cat (Perreault et al. 1995). Flexor reflex afferents can access deeply into CPG networks to reset the step cycle to a new flexion (Jankowska et al. 1967; Schomburg et al. 1998). It must be noted, however, that in these animals with reduced descending control, sensory feedback from a single input pathway is sufficient to affect CPG activity. In intact animals, manipulation of just a single type of sensory feedback is not sufficient to modulate and reset rhythmic activity (Duysens and Stein 1978; Whelan and Pearson 1997).

Related observations are found also in human experiments where transient changes in afferent activity do increase muscle activity. However, an attempt to activate load sensory feedback during the stance phase by adding a substantial weight at the center of mass was insufficient to significantly change the stance duration of the step cycle (Stephens and Yang 1999). Therefore, it is unclear to what extent CPGs and sensory feedback are integrated in the control of rhythmic motor timing in humans. There are no studies in humans, as there are in cats, that directly evaluate the exact contribution of sensory feedback to CPG output. However, indirect methodologies allow observations to be made in an intact nervous system to evaluate how the CPG regulates afferent feedback during rhythmic movement (Burke 1999; Zehr 2005). Although patterning is not accessible directly, the effects of reflexes as indexes of CPG-related modulation are. Reflexes arising because of activation of afferent projections from receptors in skin and muscle have been studied widely and support the role of locomotor CPGs in the neural control of rhythmic human movement.

Examining reflex activity and modulation during rhythmic movement provides clues that indicate CPG regulation. Reflexes, measured as changes in muscle activity, are the response to electrical or mechanical stimulation of a sensory pathway. This approximates the input-output properties of neural control where stimulation of a given sensory input and a record of the pattern of modulation of motor output during movement are compared. This approach has been used to great effect in the quadrupedal locomotor system (Burke et al. 2001) and is also effectively used in humans (Zehr and Duysens 2004; Zehr et al. 2004a). Examining the modulation of reflexes during rhythmic movement, as an indirect indicator of CPG regulation of afferent input, provides more data from which clues for CPGs in humans have been gleaned.

Clues from task- and phase-dependent modulation of reflex amplitudes.

“It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories to suit facts.”

“A Scandal in Bohemia” in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1892)

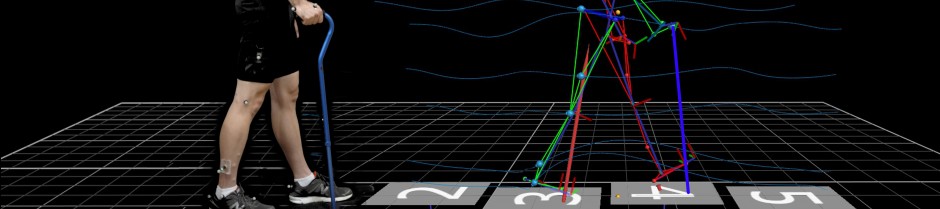

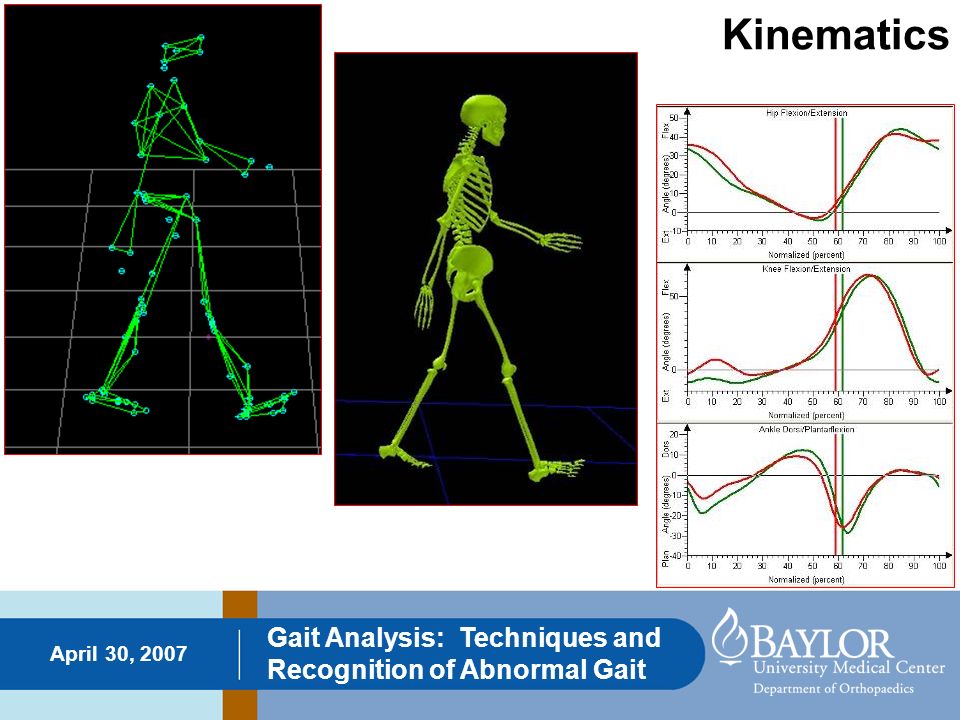

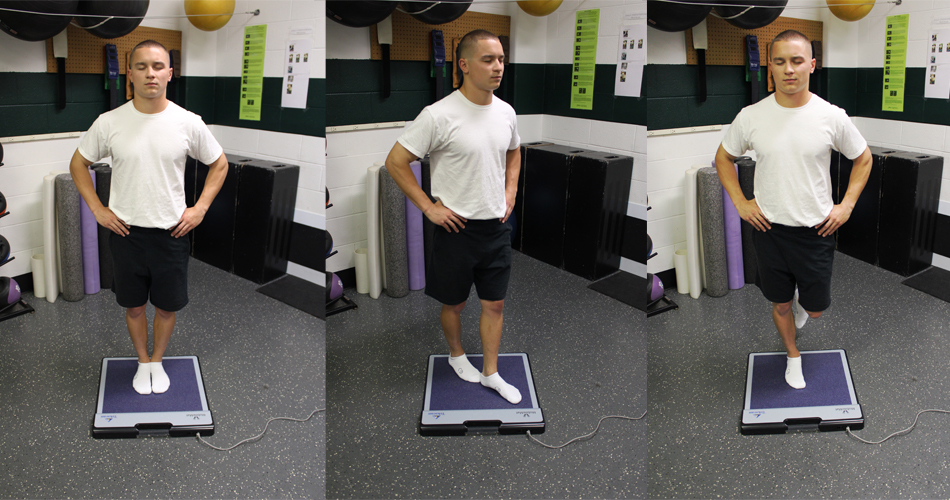

The presence of task- and phase-dependent modulation has been used to infer the activity of CPGs in humans. Task- and phase-dependent modulation of reflexes means that efficacy of sensory input varies depending on the timing within a behavior in which it occurs (Duysens et al. 1992; Van Wezel et al. 1997; Yang and Stein 1990; Zehr et al. 1997; Zehr and Stein 1999). An example of task-dependent modulation is depicted in . H-reflexes are progressively inhibited across different tasks from standing to walking to running (Stein and Capaday 1988). H-reflexes examined during walking also show phase-dependent modulation (Brooke et al. 1997; Zehr and Stein 1999). Over the course of the gait cycle, there is phasic modulation of the magnitude of the H-reflex and of the stretch reflex (the mechanical analog of the H-reflex). At the late stance phase, the reflexes in the soleus are facilitated, likely due to an increase in excitability via facilitation along Ia reflex pathways (Yang and Whelan 1993). Functionally, this assists in maintaining an upright position where the reflex is largest in stance phase when balance is required and smallest in the swing phase when free movement is required and when a reflex activation of soleus would counteract the flexion at the ankle (Capaday and Stein 1986; Verschueren et al. 2002).

Attenuation of reflexes under different behaviors. The cartoon subject depicted in the top row is shown performing 4 different motor tasks. Results show a corresponding decrease in H-reflex amplitude. Note that the M wave is held constant and that the M wave and H-reflex amplitude would be normalized to the maximal M wave for each condition across motor tasks to ensure stimulus constancy and proper comparison. [Adapted from Zehr (2002).]

Task- and phase-dependent modulation is also observed for modulation of cutaneous reflexes. In the cat, activation of sensory afferents of cutaneous receptors from the foot, with either direct skin stimulation or electrical stimulation of the nerves, causes a dramatic effect on the locomotor cycle. With stimulation of both the pad of the foot (Duysens and Pearson 1976) and dorsum of the foot (Forssberg et al. 1975), and in fictive locomotion of decerebrate-paralyzed cats (Guertin et al. 1995) or decerebrate cats with transected spinal cords (LaBella et al. 1992), cutaneous stimulation during the stance phase evoked prolongation of extension to delay the foot leaving the ground. Observations from these different spinal cat models confirm that cutaneous feedback pathways make direct connections with spinal cord networks by accessing excitation of the extensor half-center and promoting increased extensor activity (Pearson 2004).

In humans, the same observations of phase-dependent modulation of cutaneous feedback are confirmed. In some cases, modulation is so powerful that a reflex can completely reverse in sign. Such a phase-dependent reflex reversal is highlighted in the tibialis anterior, where in the same muscle, the sign of the reflex reverses from excitation in the early swing phase to inhibition at the stance transition (see ) (Duysens et al. 1992; Haridas and Zehr 2003; Yang and Stein 1990; Zehr et al. 1997).

Phase-dependent modulation and reversal of cutaneous reflex during locomotion in the tibialis anterior (TA). The electromyography (EMG) traces are from TA muscle and are the reflexes to tibial nerve stimulation once the background locomotor-related EMG has been subtracted. An arrow marks the excitatory reflex during swing, which becomes an inhibitory one at the swing-to-stance transitions. [Adapted from Yang and Stein (1990) and reprinted from Zehr and Stein (1999).]

Phase dependency is a symptomatic outcome of CPG output that serves a functional role tuned to locomotor conditions, allowing smooth progression. This keeps walking safe by incorporating afferent information at appropriate times in the walking cycle. For example, as part of the “stumble corrective response” during walking, activation of the top of the swing foot (by a physical perturbation or by electrical activation of cutaneous nerves) causes a reduction in dorsiflexion, allowing the foot to move past the perturbation and not disturb locomotor progression. However, if the same input to the foot in stance yielded similar neural coordination, the person would collapse. Thus, depending on the phase, the same sensory input is transformed by CPG activity to produce functionally relevant outcomes. Control of sensory input is so finely tuned and regulated that even among functional synergists (e.g., soleus, lateral gastrocnemius, and medial gastrocnemius), the size of a reflex can vary throughout the step cycle and can reverse in sign (see ) (Zehr et al. 1997).

Subtracted electromyograms (EMGs) of tibialis anterior (TA; top left), soleus (Sol; top right), lateral gastrocnemius (LG; bottom left), and medial gastrocnemius (MG; bottom right) muscles after superficial peroneal (SP) nerve stimulation for 1 representative subject. Throughout, the stimulus artifact has been suppressed and replaced by a flat line, atop which has been placed a thick dashed line. Each trace runs from 50 ms before stimulation to 250 ms after stimulation. Note phase-dependent reflex reversals in functional synergists. [Adapted from Zehr et al. (1997).]

Clues from mechanistic study of phase-dependent reflex modulation.

“…the problem was already one of interest, but my observations soon made me realize that it was in truth much more extraordinary than would at first sight appear.”

“The Adventure of the Crooked Man” (1893)

There has been much speculation as to how phase-dependent modulation occurs during rhythmic motor tasks. Sensory feedback itself could be involved in modulating other movement-related feedback from muscle or joint receptors (Drew and Rossignol 1987; Misiaszek et al. 1998). The same inputs that generate reflex output could alter presynaptic inhibition to change the gain from muscle spindle group Ia and II and Golgi tendon organ Ib pathways. However, phase-dependent modulation is present in the hindlimb (Quevedo et al. 2005b) and forelimb of the cat (Hishinuma and Yamaguchi 1989), examined by intracellular analysis of reflex pathways underlying the stumble corrective reflex during fictive locomotion, when movement is completely absent (Andersson et al. 1978; Schomburg and Behrends 1978). The observation of phase-dependent reflex modulation in the fictive preparation means reflex modulation must be ascribed, at least in part, to spinal CPG regulation (Andersson et al. 1978; LaBella et al. 1992). Convergence of information from locomotor CPGs onto segmental interneurons within feedback pathways has been proposed as the source of the observed reflex modulation (Seki and Yamaguchi 1997). Thus, along with presynaptic inhibition, the CPG modulates the amplitude of primary afferent depolarizations in afferent reflex pathways (Gossard and Rossignol 1990).

Thus CPGs are likely responsible for regulating and balancing the overall strength of excitatory and inhibitory connections in the spinal cord that allow sensory information to be incorporated (Abraham and Loeb 1985; Andersson et al. 1978; Dietz 2002; Dietz et al. 2001; Duysens and Van De Crommert 1998; Duysens et al. 1990, 1992; Forssberg 1979; Komiyama et al. 2000; Quevedo et al. 2005a; Van Wezel et al. 1997; Yang and Stein 1990; Zehr and Duysens 2004; Zehr et al. 2004b). With intracellular recording, spinal interneurons in spinal cord circuits can be observed to participate in reflex modulation (Bui et al. 2016; Quevedo et al. 2005a). In humans there are several characteristics that reveal a central control mechanism in modulating sensory feedback for task- and phase-dependent modulation. These characteristics include that reflex modulation is independent of changes in background EMG, only occurs with active rhythmic but not passive movement, and is not influenced by feedback in other sensory pathways.

In static tasks, there is a strong linear relationship between reflex and background muscle activity, whereas during walking, reflexes are relatively uncorrelated and do not follow background activation (Haridas and Zehr 2003; Van Wezel et al. 1997; Yang and Stein 1990; Zehr et al. 1997). Such observations suggest that modulation occurs at a premotoneuronal level (Duysens and Tax 1994; Matthews 1986). An example is shown in where kinematics of knee movement were matched to locomotor amplitudes during treadmill walking (Zehr et al. 2007a). Cutaneous reflexes evoked in knee extensor muscle vastus lateralis were tightly correlated with background EMG level during voluntary knee extension but completely dissociated during walking.

Strong correlation between reflex amplitude during voluntary knee extension is absent during walking due to the modulation of presumed central pattern generator activity. EMG, electromyography. [Adapted from Zehr et al. (2007a).]

In the case of muscle afferent pathways, an increased reflex attenuation during tasks implies a premotoneuronal mechanism, because the response is independent of locomotor EMG (Stein and Capaday 1988). Most likely, it is presynaptic inhibition of Ia afferent transmission from CPGs as a mechanism for inhibition of the same pathway, because presynaptic inhibition is a major mechanism influencing spinal cord excitability during interlimb locomotor activity (Capaday and Stein 1986; Crenna and Frigo 1987; Zehr 2006).

There is more evidence that spinal CPGs are responsible for task- and phase-dependent modulation of sensory feedback during locomotion. When a CPG for rhythmic movement is not active, as in passive movements, phase-dependent modulation is absent (Brooke et al. 1999; Carroll et al. 2005). This suggests that modulation is not the result of movement-related afferent feedback, associated with the passive movement, but is driven by a central mechanism. This was confirmed with the observation that there was no effect on cutaneous reflex modulation when muscle spindle sensory receptors were activated from quadriceps muscles with patellar taps (Brooke et al. 1999). A central mechanism, such as CPG networks, is predicted to be responsible for phase-dependent modulation because reflex modulation does not occur with passive movement, nor does the interaction of other reflex pathways affect modulation (Brooke et al. 1999).

The way in which CPG neurons transform cutaneous input changes as a function of the locomotor cycle. The fact that cutaneous feedback during walking can cause a flexor response during the swing phase, and an extensor response during the stance phase, in the same muscle suggests that parallel excitatory and inhibitory cutaneous pathways could exist between cutaneous receptors and motoneuron pools (Yang and Stein 1990). Indeed, the existence of parallel excitatory and inhibitory pathways to motoneurons was revealed by analysis with poststimulus time histograms (PSTH) of single motor units from the tibialis anterior during walking (De Serres et al. 1995). With posterior tibial nerve stimulation, PSTH showed that the same motor unit was excited during swing and inhibited during the transition from swing to stance. The opening and closing of these parallel pathways depends on the phase of the rhythmic cycle where CPGs act to govern the overall strength of the excitatory and inhibitory connections in these parallel pathways (Duysens et al. 1992; Yang and Stein 1990).

Summary of the evidence from task- and phase-dependent modulation of reflex amplitudes.

The importance of the CPG is its ability not only to generate repetitive cycles but also to receive, interpret, and predict the appropriate action at each part of the step cycle. This is made possible by constant input from peripheral sources to update and sculpt CPG output. In other animals, this relationship can be directly shown, but in humans, examining task- and phase-dependent modulation of reflexes during rhythmic movement provides an indirect indicator of the relationship between CPG regulation and afferent input. In humans, these observations provide some of the main data on which the concept of spinal CPGs has been built. There are several characteristics that reveal a central control mechanism in modulating sensory feedback. These characteristics include the facts that reflexes are modulated according to the task- and phase- of movement, that reflexes are independent of changes in background EMG, that modulation only occurs with voluntary movement and not passive movement, and that modulation is not influenced by feedback in other sensory pathways. Together, these observations are evidence that a spinal CPG is responsible for the fine-tuning of sensory feedback during rhythmic movement.

3) Some Evidence for Similar Neuronal Networks Recruited into Different Rhythmic Human Motor Tasks

“You know my methods. Apply them!”

The Hound of the Baskervilles (1902)

In cats, the pattern-generating circuits for different rhythmic functions overlap with shared networks to produce the behaviors they generate. Functional temporal reversals during backward locomotion provide evidence of the adaptability of pattern generators in the control of locomotion. In the cat, backward walking is produced by a phase shift in activation of unit burst generators controlling flexion and extension of knee and hip muscles (Buford and Smith 1993). If shared circuitry for various rhythmic movements is also within the human spinal cord, it should be observed as a characteristic of human reflex modulation. Indeed, reflex modulation, as well as joint power, limb kinematics, and EMG activity in some muscles, is essentially reversed in time during backward walking (Duysens et al. 1996; Thorstensson 1986; Winter et al. 1989). Cutaneous reflexes are thought to be regulated by an equivalent neural CPG mechanism, because responses are phase-reversed in lower leg muscles such as tibialis anterior (Duysens et al. 1996).

Reflex modulation in pedaling (Brooke et al. 1997; Brown and Kukulka 1993) is similar to that in walking (Yang and Stein 1990), suggesting that related neural circuitry may be operational in both tasks (Ting et al. 1999). Similar to observations in walking, forward and backward arm cycling are also regulated by an equivalent neural mechanism, where at similar phases in the movement cycle, responses of corresponding sign and amplitude were seen regardless of movement direction (Zehr and Hundza 2005). This extended also to leg cycling, where a simple reversal in reflex patterning suggests that forward and backward leg cycling are regulated by a similar neural mechanism (Zehr et al. 2009a). In a further example, in human infants, different directions of walking are ascribed to flexible use of common locomotor spinal circuits (Lamb and Yang 2000).

Comparable coordination patterns between activities involving all four limbs moving simultaneously and rhythmically also exist. For example, during walking, creeping, and swimming, responses that are suggestive of similar CPG output in all activities have been shown (Wannier et al. 2001). Commonalities in cutaneous reflex amplitudes in arm and leg muscles were also seen across level walking, incline walking, and stair climbing (Lamont and Zehr 2006). In other quadrupedal tasks, reflexes were modulated in a similar way across walking, arm and leg cycling, and arm-assisted recumbent stepping, where similar phase-dependent modulation was observed despite differences in movement kinematics (Zehr et al. 2007a). This led to the conceptualization of relatively equivalent partitioning of the locomotor cycle across different tasks (see ). In the damaged nervous system with descending disruptions after stroke, common neural patterning from conserved subcortical regulation persisted (Klarner et al. 2014b). This was evidenced by a similarity in reflex modulation between different rhythmic tasks (see ). These findings imply that networks for arm and leg coordination could reside in subcortical areas, because damage to the brain following stroke still expressed common neural regulation (Klarner et al. 2014b).

Comparison of different human locomotor behaviors involving all 4 limbs. [Adapted from Zehr et al. (2007a).]

Ensemble grand-average subtracted reflex traces from all phases and all subjects for arm and leg (A&L) cycling and walking. Note that there is a similar pattern of cutaneous reflex modulation across tasks. Despite some changes in amplitudes, the general pattern is conserved. EMG, electromyography; TA, tibialis anterior; PD, posterior deltoid. [Adapted from Klarner et al. (2014b).]

Summary of the evidence across different rhythmic locomotor behaviors.

The “common core hypothesis” (Zehr 2005) describes the concept that neural control, evidenced by examining similarities in reflex modulation, is conserved across rhythmic arm and leg movements for different tasks such as cycling, walking, stepping, and arm and leg cycling and can be activated for different directions of action. That is, a flexible central mechanism is likely responsible for regulating various types of rhythmic movement in a similar oscillatory fashion with a common core of subcortical elements expressing neural activity to produce the basic pattern of arm and leg movement (Klarner et al. 2014b; Zehr 2005; Zehr et al. 2007a). The ability of a muscle to contribute to more than one function, with the expression of each under neural modulation, gives the control scheme flexibility and thus the capability to execute a variety of tasks (Ting et al. 1999).

4) Some Evidence of Distributed Locomotor Networks and Interlimb Connectivity in Human Locomotion

“I make a point of never having any prejudices, and of following docilely where fact may lead me.”

“The Reigate Squires” in The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes (1893)

As outlined above, EMG and reflex studies support the role of locomotor CPGs in the neural control of rhythmic human movement. In other animals, CPG networks are distributed along the spinal cord for functional integration between the forelimbs and hindlimbs. Given the potential for evolutionary conservation, we presume that in humans, CPG networks can be found in the cervical spinal cord and produce rhythmic activity for arm swing. We would predict that, reminiscent of what is demonstrated in quadruped locomotor studies, CPGs for all limbs are interconnected in the central nervous system.

Clues from rhythmic arm activity.

“When one tries to rise above Nature one is liable to fall below it.”

“The Adventure of the Creeping Man” in The Case Book of Sherlock Holmes (1927)