How do personalized hydration strategies impact athletic performance and safety. What are the key physiological, behavioral, and logistical factors that influence an athlete’s fluid needs. How can clinicians assess hydration status in athletes and provide practical hydration solutions.

The Importance of Proper Hydration for Athletes

Maintaining optimal hydration is crucial for athletes to perform at their best and stay safe during sports activities. Euhydration, the state of preserving body water within its ideal homeostatic range, is essential for sustaining life and athletic performance. Water makes up 50-70% of total body mass and is distributed between intracellular (65%) and extracellular (35%) spaces.

Proper hydration plays a vital role in numerous physiological functions that impact athletic performance, including:

- Regulating body temperature

- Transporting nutrients and oxygen to cells

- Removing waste products

- Lubricating joints

- Maintaining blood volume and cardiovascular function

Dehydration can significantly impair an athlete’s performance and increase the risk of heat-related illnesses. Even mild dehydration of just 2% body mass loss can negatively affect cognitive function, coordination, and endurance capacity.

Factors Influencing Fluid Needs in Athletes

An athlete’s fluid requirements during sports activities are influenced by various factors:

Environmental Conditions

Temperature, humidity, altitude, and air flow all impact sweat rates and fluid loss. Hot and humid environments increase fluid needs, while cold environments may reduce thirst sensation despite ongoing fluid losses.

Sport-Specific Demands

The intensity, duration, and nature of the sport affect hydration needs. Endurance events typically require more fluid intake than short-duration, high-intensity activities.

Individual Characteristics

Factors such as body size, sweat rate, heat acclimatization, and fitness level influence an athlete’s fluid requirements. Larger athletes and those with higher sweat rates generally need more fluids to maintain hydration.

Logistical Constraints

Access to fluids during training or competition can vary greatly between sports. Some activities allow frequent hydration opportunities, while others may restrict fluid intake to specific times.

Assessing Hydration Status in Athletes

Accurately assessing an athlete’s hydration status is crucial for developing effective hydration strategies. Several methods can be used to evaluate hydration levels:

Urine Color and Volume

Monitoring urine color and volume provides a simple, non-invasive indicator of hydration status. Pale yellow urine generally indicates proper hydration, while dark, concentrated urine suggests dehydration.

Body Weight Changes

Tracking changes in body weight before and after exercise can help estimate fluid losses. A loss of more than 2% of body weight indicates significant dehydration.

Thirst Sensation

While thirst can be a useful indicator of hydration needs, it’s important to note that thirst sensation may lag behind actual fluid requirements, especially during intense exercise or in hot conditions.

Bioelectrical Impedance

This method uses electrical currents to estimate body water content and can provide more precise measurements of hydration status.

Developing Personalized Hydration Strategies

Creating effective hydration plans for athletes requires a personalized approach that considers individual needs and sport-specific factors:

Pre-Exercise Hydration

Ensuring proper hydration before exercise is crucial. Athletes should aim to begin activities in a euhydrated state by consuming adequate fluids in the hours leading up to exercise.

During-Exercise Fluid Intake

Fluid intake during exercise should aim to replace sweat losses and prevent excessive dehydration. The amount and frequency of fluid consumption will vary based on individual sweat rates, exercise intensity, and environmental conditions.

Post-Exercise Rehydration

Replenishing fluid losses after exercise is essential for recovery. Athletes should aim to consume 150% of their fluid losses within 2-4 hours post-exercise to account for ongoing urine losses.

Practical Hydration Solutions for Different Sports

Implementing effective hydration strategies often requires creative solutions tailored to the specific demands and constraints of each sport:

Endurance Sports

For activities like marathon running or long-distance cycling, consider:

- Utilizing hydration belts or backpacks for easy access to fluids

- Planning refueling stations along the route

- Incorporating electrolyte-rich beverages to replace losses from prolonged sweating

Team Sports

In sports like soccer or basketball, strategies may include:

- Maximizing hydration during timeouts and halftime breaks

- Using personalized water bottles for quick identification

- Educating athletes on the importance of proactive hydration

Indoor Sports

For activities in climate-controlled environments, consider:

- Placing easily accessible water stations around the training area

- Encouraging regular hydration breaks during practice sessions

- Monitoring indoor temperature and humidity levels to adjust fluid needs

Overcoming Hydration Challenges in Extreme Environments

Athletes competing in extreme environments face unique hydration challenges that require specialized strategies:

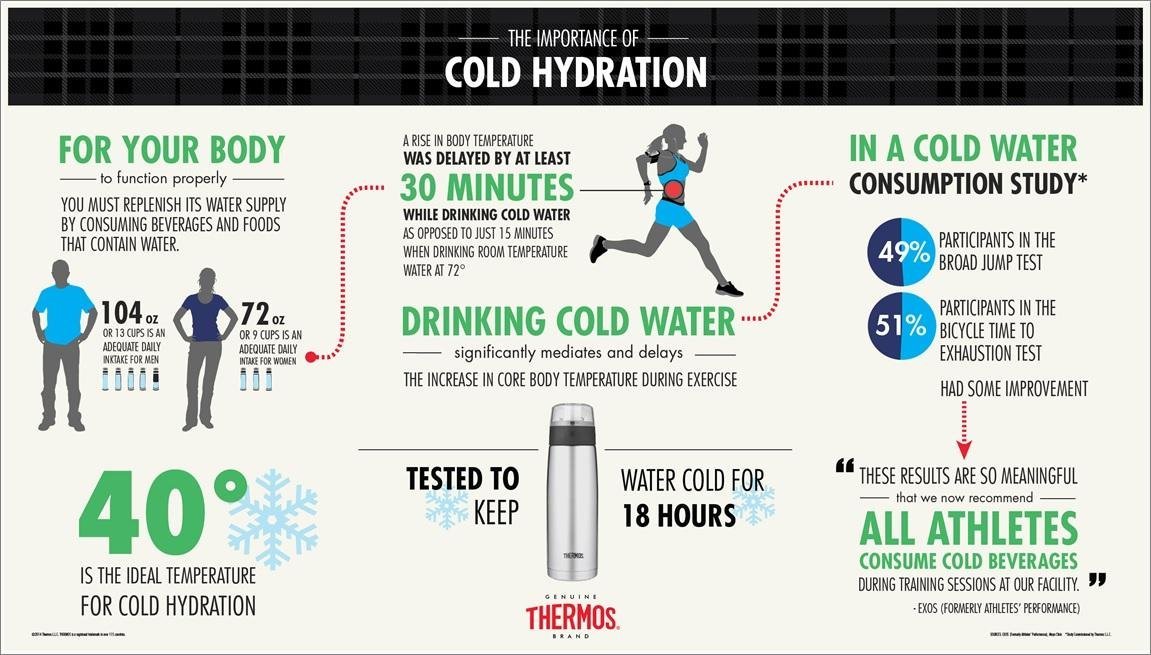

Hot and Humid Conditions

In hot and humid environments, sweat rates increase dramatically, elevating the risk of dehydration and heat-related illnesses. To combat these challenges:

- Implement pre-cooling techniques to reduce core body temperature before exercise

- Use cold fluids and ice slurries to enhance cooling during activity

- Increase fluid intake to match elevated sweat rates

- Monitor urine color and body weight changes more frequently

Cold Environments

While fluid losses may be less apparent in cold conditions, dehydration can still occur due to increased respiratory water loss and reduced thirst sensation. Strategies for cold environments include:

- Encouraging regular fluid intake despite reduced thirst cues

- Using insulated hydration systems to prevent fluids from freezing

- Consuming warm fluids to aid in maintaining core body temperature

High Altitude

At high altitudes, increased respiratory water loss and diuresis can lead to accelerated dehydration. To address these issues:

- Increase fluid intake to compensate for elevated losses

- Monitor urine output and color more closely

- Consider using electrolyte-rich beverages to maintain proper fluid balance

The Role of Electrolytes in Athletic Hydration

Electrolytes play a crucial role in maintaining proper hydration and supporting athletic performance. These electrically charged minerals, including sodium, potassium, calcium, and magnesium, are essential for various physiological functions:

Fluid Balance

Electrolytes, particularly sodium, help regulate fluid balance between intracellular and extracellular spaces. This is crucial for maintaining blood volume and supporting cardiovascular function during exercise.

Muscle and Nerve Function

Electrolytes are vital for proper muscle contraction and nerve signaling. Imbalances can lead to muscle cramps, fatigue, and impaired performance.

Hydration Status

The presence of electrolytes in fluids can enhance fluid retention and absorption, improving overall hydration status.

For many athletes, especially those engaging in prolonged or intense exercise in hot conditions, incorporating electrolyte-rich beverages or supplements into their hydration strategy can be beneficial. However, the specific electrolyte needs can vary based on individual factors and the nature of the activity.

Hydration Strategies for Different Types of Athletes

While the fundamental principles of hydration remain consistent, the specific strategies may vary depending on the type of athlete and their sport:

Endurance Athletes

Marathoners, triathletes, and long-distance cyclists face unique hydration challenges due to the prolonged nature of their events. Key considerations include:

- Developing a comprehensive hydration plan that accounts for the entire duration of the event

- Balancing fluid intake with electrolyte replacement to prevent hyponatremia

- Practicing hydration strategies during training to optimize individual approaches

Team Sport Athletes

Athletes in sports like soccer, basketball, or rugby need to maintain hydration despite intermittent high-intensity efforts and limited access to fluids during play. Strategies may include:

- Maximizing hydration opportunities during breaks in play

- Using rapid hydration techniques to quickly replenish fluids during short rest periods

- Individualizing hydration plans based on positional demands and personal sweat rates

Strength and Power Athletes

Weightlifters, sprinters, and other power athletes may have different hydration needs due to the short-duration, high-intensity nature of their events. Considerations include:

- Focusing on maintaining hydration status between training sessions and competitions

- Balancing fluid intake to support performance without causing discomfort or excess body weight

- Addressing hydration needs specific to weight class competitions

The Impact of Hydration on Cognitive Function and Decision-Making in Sports

Proper hydration is not only crucial for physical performance but also plays a significant role in cognitive function and decision-making abilities, which are essential in many sports. Research has shown that even mild dehydration can negatively impact various aspects of cognitive performance:

Attention and Focus

Dehydration can lead to decreased attention span and difficulty maintaining focus, which can be particularly detrimental in sports requiring high levels of concentration and quick reactions.

Decision-Making Speed

Studies have demonstrated that dehydration can slow down decision-making processes, potentially impacting an athlete’s ability to make split-second choices during competition.

Mood and Perception

Inadequate hydration has been linked to increased perception of task difficulty and negative mood states, which can affect an athlete’s motivation and performance.

To support optimal cognitive function during sports activities, athletes should:

- Prioritize hydration before, during, and after cognitive-demanding tasks or competitions

- Monitor hydration status regularly, especially in situations where cognitive performance is crucial

- Educate themselves on the signs of cognitive impairment related to dehydration

Innovative Hydration Technologies and Their Application in Sports

Advancements in technology have led to the development of innovative tools and methods to support athlete hydration. These technologies can provide more accurate assessments of hydration status and help optimize fluid intake strategies:

Wearable Hydration Monitors

These devices use various methods, such as bioelectrical impedance or sweat analysis, to provide real-time feedback on hydration status. Athletes and coaches can use this information to make immediate adjustments to fluid intake during training or competition.

Smart Water Bottles

Equipped with sensors and connected to smartphone apps, these bottles can track fluid intake, set hydration goals, and provide reminders to drink. This technology can be particularly useful for athletes who struggle to maintain consistent hydration habits.

Sweat Analysis Patches

These wearable patches can analyze the electrolyte content of an athlete’s sweat, providing valuable information for creating personalized hydration and electrolyte replacement strategies.

Hydration Testing Devices

Portable devices that can quickly analyze urine or saliva samples to assess hydration status are becoming more accessible, allowing for more frequent and convenient monitoring.

While these technologies offer exciting possibilities for optimizing hydration strategies, it’s important to remember that they should be used in conjunction with, not as a replacement for, traditional hydration assessment methods and individualized approaches developed with healthcare professionals.

Educating Athletes on Hydration Best Practices

Empowering athletes with knowledge about proper hydration is crucial for implementing effective strategies and promoting long-term healthy habits. Key areas of education should include:

Understanding Hydration Physiology

Provide athletes with a basic understanding of how the body regulates fluid balance and the impact of dehydration on performance and health.

Recognizing Dehydration Signs

Teach athletes to identify early signs of dehydration, such as thirst, dark urine, and decreased performance, so they can take proactive measures.

Personalized Hydration Strategies

Help athletes develop individualized hydration plans based on their specific needs, sweat rates, and sport requirements.

Proper Use of Sports Drinks

Educate athletes on when and how to use sports drinks effectively, including understanding the differences between various types of beverages and their appropriate applications.

Hydration in Different Environments

Provide guidance on adjusting hydration strategies for various environmental conditions, including hot, cold, and high-altitude settings.

Effective education programs can utilize a variety of methods, including:

- Interactive workshops and seminars

- Hands-on demonstrations of hydration assessment techniques

- Integration of hydration education into regular training sessions

- Use of technology, such as apps or online resources, to reinforce learning

By fostering a deeper understanding of hydration principles and practices, athletes can become more proactive and effective in managing their fluid needs, ultimately leading to improved performance and reduced risk of hydration-related issues.

Practical Hydration Solutions for Sports

Nutrients. 2019 Jul; 11(7): 1550.

,1,*,2,1,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,1,10,4,11,12,13,14,1,15 and 16

Luke N. Belval

1Korey Stringer Institute, Department of Kinesiology, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT 06269, USA

Yuri Hosokawa

2Faculty of Sport Sciences, Waseda University, Saitama 359-1192, Japan

Douglas J. Casa

1Korey Stringer Institute, Department of Kinesiology, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT 06269, USA

William M. Adams

3Department of Kinesiology, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Greensboro, NC 27402, USA

Lawrence E. Armstrong

4Department of Kinesiology, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT 06269, USA

Lindsay B.

Baker

Baker

5Gatorade Sports Science Institute, Barrington, IL 60010, USA

Louise Burke

6Sports Nutrition, Australian Institute of Sport, Canberra, ACT 2617, Australia

Samuel Cheuvront

7Sports Science Synergy, LLC, Franklin, MA 02038, USA

George Chiampas

8U.S. Soccer, Chicago, IL 60616, USA

José González-Alonso

9Centre for Human Performance, Exercise and Rehabilitation, Brunel University London, Uxbridge UB8 3PH, UK

Robert A. Huggins

1Korey Stringer Institute, Department of Kinesiology, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT 06269, USA

Stavros A. Kavouras

10Hydration Science Lab, College of Health Solutions, Arizona State University, Phoenix, AZ 85004, USA

Elaine C. Lee

4Department of Kinesiology, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT 06269, USA

Brendon P. McDermott

11Department of Health, Human Performance and Recreation, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR 72701, USA

Kevin Miller

12Department of Rehabilitation and Medical Sciences, Central Michigan University, Mount Pleasant, MI 48859, USA

Zachary Schlader

13Department of Exercise and Nutrition Sciences, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY 14214, USA

Stacy Sims

14Faculty of Health, Sport and Human Performance, University of Waikato, Hamilton 3216, New Zealand

Rebecca L.

Stearns

Stearns

1Korey Stringer Institute, Department of Kinesiology, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT 06269, USA

Chris Troyanos

15International Institute of Race Medicine, Plymouth, MA 02360, USA

Jonathan Wingo

16Department of Kinesiology, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL 35487, USA

1Korey Stringer Institute, Department of Kinesiology, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT 06269, USA

2Faculty of Sport Sciences, Waseda University, Saitama 359-1192, Japan

3Department of Kinesiology, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Greensboro, NC 27402, USA

4Department of Kinesiology, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT 06269, USA

5Gatorade Sports Science Institute, Barrington, IL 60010, USA

6Sports Nutrition, Australian Institute of Sport, Canberra, ACT 2617, Australia

7Sports Science Synergy, LLC, Franklin, MA 02038, USA

8U. S. Soccer, Chicago, IL 60616, USA

S. Soccer, Chicago, IL 60616, USA

9Centre for Human Performance, Exercise and Rehabilitation, Brunel University London, Uxbridge UB8 3PH, UK

10Hydration Science Lab, College of Health Solutions, Arizona State University, Phoenix, AZ 85004, USA

11Department of Health, Human Performance and Recreation, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR 72701, USA

12Department of Rehabilitation and Medical Sciences, Central Michigan University, Mount Pleasant, MI 48859, USA

13Department of Exercise and Nutrition Sciences, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY 14214, USA

14Faculty of Health, Sport and Human Performance, University of Waikato, Hamilton 3216, New Zealand

15International Institute of Race Medicine, Plymouth, MA 02360, USA

16Department of Kinesiology, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL 35487, USA

Received 2019 May 15; Accepted 2019 Jul 3.

Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).This article has been cited by other articles in PMC.

This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).This article has been cited by other articles in PMC.

Abstract

Personalized hydration strategies play a key role in optimizing the performance and safety of athletes during sporting activities. Clinicians should be aware of the many physiological, behavioral, logistical and psychological issues that determine both the athlete’s fluid needs during sport and his/her opportunity to address them; these are often specific to the environment, the event and the individual athlete. In this paper we address the major considerations for assessing hydration status in athletes and practical solutions to overcome obstacles of a given sport. Based on these solutions, practitioners can better advise athletes to develop practices that optimize hydration for their sports.

Keywords: fluid replacement, athletics, exercise

1.

Introduction

Introduction

Maintaining euhydration, the state of preserving body water within its optimal homeostatic range, is essential to sustain life. Water contributes 50–70% of total body mass and is compartmentalized within both intracellular (65%) and extracellular (35%) spaces [1]. Euhydration is typically maintained over the course of day-to-day life via behavioral and biological controls [2]. However, exercise can cause an acute disruption to fluid balance, challenging the athlete’s goal of optimal performance and safety during exercise, especially in hot environmental conditions. The process of incurring a fluid deficit is known as dehydration, while the outcome is defined as hypohydration. The loss of body water during exercise exacerbates physiological and perceptual strain [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10] and it is well established that these changes can impair endurance performance, particularly in hot environments and may increase the risk of exertional heat illness [11,12,13,14,15,16,17].

While the sensation of thirst, a centrally mediated response to body water deficits, is useful in dictating the need for fluid intake during daily life, thirst is relatively insensitive in acutely tracking hydration status during exercise [18,19]. Maintaining an optimal state of hydration during exercise becomes more complicated depending on the sport, type of activity and availability of fluid. Optimal hydration is dependent on many factors but can generally be defined during exercise as avoiding losses greater than 2–3% of body mass while also avoiding overhydration [15]. Furthermore, during exercise, it is not uncommon for individuals to involuntarily dehydrate, in which they consume less fluid than their fluid needs. Excessive fluid intake can also be problematic, with hyponatremia developing in severe cases of overhydration [15]. Inappropriate management of fluid intake resulting in hypohydration, or hyperhydration, can be detrimental for performance and in some circumstances, increases health risk.

Current consensus recommends that good hydration practices include: (1) beginning exercise in a state of euhydration, (2) preventing excessive hypohydration during exercise, and (3) replacing remaining losses following exercise prior to the next exercise bout [15,20,21]. These practices attenuate the adverse effects of acute dehydration on physical activity and health [15]. However, it is acknowledged that fluid needs are individualistic and rely on factors such as personal sweat rate, exercise mode, exercise intensity, environmental conditions and exercise duration () [14,15,22,23,24,25]. Furthermore, characteristics and rules unique to each sport environment in which it is played, event uniform and equipment, and the availability of fluid during both training and competition may greatly influence the ability to optimize hydration during activity. The Korey Stringer Institute and Gatorade convened a meeting to address these issues as they relate to athletes. The purpose of these proceedings is to discuss practical strategies to assess and tailor hydration for sports. This manuscript will specifically focus on the factors that underlie fluid needs and provide guidance to clinicians and practitioners on how to plan for these needs in the context of a given activity.

This manuscript will specifically focus on the factors that underlie fluid needs and provide guidance to clinicians and practitioners on how to plan for these needs in the context of a given activity.

Factors that contribute to the risk of hypohydration or hyperhydration during exercise.

2. Hydration Assessment

Hydration assessment can be utilized to indicate one’s current hydration state, but if taken serially, it can also be used to track changes in hydration and indicate fluid needs (i.e., during a bout of physical activity). While various methods of hydration assessment exist, there is no single method that can serve as a criterion measure to assess hydration status in all settings (i.e., day-to-day life and exercise, etc.). Plasma osmolality, changes in plasma volume, and the volume, osmolality and specific gravity of urine are the most commonly published metrics to assess changes in hydration status in clinical settings [26]. The use of these measures in field applications is often impractical, due to the methods or equipment needed to acquire the measure (e. g., a needle stick to draw blood or providing a urine sample) as well as the sensitivity of the measure.

g., a needle stick to draw blood or providing a urine sample) as well as the sensitivity of the measure.

In field applications, the careful assessment of changes in body mass over a bout of physical activity provides a reasonably accurate assessment of body water deficits incurred during the session, since sweat loss and fluid intake during the session underpin the major changes in body mass and body water content. This is true for most sporting activities conducted over a duration of <2–3 h; however, during very prolonged and strenuous exercise (e.g., ultra-endurance races), other factors that cause mass changes, metabolic water production and the liberation of stored water become numerically important and undermine the utility of this assessment [15,27,28]. A comparison of body mass pre- and post-exercise will help guide the athlete in understanding whether their hydration strategy during activity was effective in achieving acceptable fluid balance as well as knowing the volume of fluids that are needed following exercise to return to baseline hydration levels prior to the next exercise session. The methodology for assessing sweat losses is to assess the athlete’s body mass before and after exercise with care to avoid or account for substantial amounts of fluid trapped in hair and clothes. Accounting for any fluid consumed or urine excreted, the difference between the masses can be used to calculate the amount of sweat lost as well as the residual fluid deficit that should be addressed in post-exercise recovery plans [29].

The methodology for assessing sweat losses is to assess the athlete’s body mass before and after exercise with care to avoid or account for substantial amounts of fluid trapped in hair and clothes. Accounting for any fluid consumed or urine excreted, the difference between the masses can be used to calculate the amount of sweat lost as well as the residual fluid deficit that should be addressed in post-exercise recovery plans [29].

A useful paradigm for tracking daily changes in hydration status in sporting situations is to consider a combination of assessments to track daily changes. The monitoring of daily changes in body mass, coupled with urine color and thirst sensation status provides adequate sensitivity for most athletic situations [30]. Cheuvront and Kenefick established useful criteria for these variables as body mass changes greater than 1.1%, a conscious desire for water (thirst), and dark-colored urine (>5 a.u. on an 8-a.u. scale [31]) indicating varying degrees of fluid inadequacy [32]. Two of these factors combined suggest daily fluid intake is likely inadequate, while all three factors indicate that daily fluid intake is very likely inadequate. It should be noted that this assessment technique is based on first morning values and requires baseline body mass values to provide the most useful information to athletes.

Two of these factors combined suggest daily fluid intake is likely inadequate, while all three factors indicate that daily fluid intake is very likely inadequate. It should be noted that this assessment technique is based on first morning values and requires baseline body mass values to provide the most useful information to athletes.

Practical Solutions:

(1)

Carefully monitor acute changes in body mass over an exercise bout to determine sweat rate, adequacy of fluid replacement and fluid needs for recovery for that session. Consider how well this can be used to evaluate general hydration strategies in similar situations.

(2)

Use changes in body mass, urine color and thirst upon awakening to track daily changes in hydration status.

3. Exercise Structure

Body fluid loss during sport or exercise largely results from sweating. Net fluid balance is modulated to a certain extent by drinking. Rate of sweating is primarily a function of metabolic heat production [33], but can be modified by environment, clothing, acclimatization and hydration status [7,34]. As the primary mechanism of heat dissipation in many environments, the evaporation of sweat is vital for regulating body temperature, even during exercise in temperate weather. However, this heat dissipation is accompanied by typical fluid losses of ~0.5–1.9 L/h [35].

As the primary mechanism of heat dissipation in many environments, the evaporation of sweat is vital for regulating body temperature, even during exercise in temperate weather. However, this heat dissipation is accompanied by typical fluid losses of ~0.5–1.9 L/h [35].

Exercise intensity is the main factor that determines metabolic heat production, meaning that the rate of fluid losses from sweat for a given exercise session can be partially explained by the intensity of the exercise [36]. Total fluid losses are a result of the sweat rate of a given exercise intensity and the total duration of that activity [27]. In most circumstances there is an inverse relationship between the exercise intensity of a session and the duration of that session. However, given the wide variability in individual sweat rates, the unique interplay between intensity, duration and sweat rate must be considered in unison. For example, a runner with a 2 L/h sweat rate who completes a marathon in 2 h will accumulate the same fluid losses as a runner with a 1 L/h sweat rate that completes the race in 4 h. In and , we define exercise intensity of a range of sporting activities into three distinct categories (High, Moderate, Low), based on typical practice and competition structures on the principles described above but comprehensive plans should consider individual athletes.

In and , we define exercise intensity of a range of sporting activities into three distinct categories (High, Moderate, Low), based on typical practice and competition structures on the principles described above but comprehensive plans should consider individual athletes.

Table 1

Team Sport Factors That Influence Hypohydration.

| Sport | Availability of Fluid | Environment | Intensity | Hypohydration Risk | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training | Competition | Training | Competition | Training | Competition | Training | Competition | |

| Basketball | High | High | Low | Low | Mod | Mod | Low | Low |

| Ice Hockey | High | High | Low | Low | Mod | High | Mod | Mod |

| Football | High | High | Mod | Mod | Mod | High | Mod | Mod |

| Baseball | High | High | Mod | Mod | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Softball | High | High | Mod | Mod | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Volleyball | High | High | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Soccer | Mod | Low | Mod | Mod | Mod | High | Mod | High |

| Lacrosse | High | High | Mod | Mod | Mod | Mod | Mod | Mod |

| Rugby | High | Low | Mod | Mod | Mod | High | Mod | High |

Table 2

Individual Sport Factors That Influence Hypohydration.

| Sport | Availability of Fluid | Environment | Intensity | Hypohydration Risk | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training | Competition | Training | Competition | Training | Competition | Training | Competition | |

| Tennis | High | Mod | Mod | Mod | High | High | Mod | Mod |

| Wrestling | High | High | Mod | Mod | High | High | High | Low |

| Gymnastics | High | High | Low | Low | Mod | Low | Low | Low |

| Running (<1 h) | Low | High | Mod | Mod | High | High | Low | Low |

| Running (1–2 h) | Low | High | Mod | Mod | Mod | Mod | Mod | Mod |

| Running (>2 h) | Low | High | Mod | Mod | Low | Mod | Mod | Mod |

| Cycling (<1 h) | High | High | Mod | Mod | High | High | Low | Low |

| Cycling (>2 h) | Mod | Mod | Mod | Mod | Mod | Mod | Low | High |

| Swimming | High | High | Low | Low | High | High | Low | Low |

| Triathlon (<2 h) | ||||||||

| Swim | Low | Low | Low | Low | Mod | Mod | Low | Low |

| Bike | Mod | High | Mod | Mod | Mod | Mod | Low | Low |

| Run | Low | High | Mod | Mod | Mod | Mod | Low | Low |

| Triathlon (2–5 h) | ||||||||

| Swim | Low | Low | Low | Low | Mod | Mod | Low | Low |

| Bike | Mod | High | Mod | Mod | Mod | Mod | Low | Low |

| Run | Low | High | Mod | Mod | Mod | Mod | Low | Low |

| Triathlon (5–9 h) | ||||||||

| Swim | Low | Low | Low | Low | Mod | Mod | Low | Low |

| Bike | Mod | High | Mod | Mod | Mod | Mod | Mod | Mod |

| Run | Low | High | Mod | Mod | Mod | Mod | Mod | Mod |

| Triathlon (>9 h) | ||||||||

| Swim | Low | Low | Low | Low | Mod | Mod | Low | Low |

| Bike | Mod | High | Mod | Mod | Mod | Mod | Mod | Mod |

| Run | Low | High | Mod | Mod | Mod | Mod | Mod | Mod |

For sports like cycling and running, the influence of exercise intensity and duration on fluid needs is very easy to determine given the consistent nature of exercise. demonstrates the relationship between duration and target fluid replacement for steady-state exercise. However, as shown in , some of the most common sports involve supramaximal exercise in short bursts with longer breaks. In this case, individuals should regard an overall average of exercise intensity rather than the maximal effort during the exercise bout when determining optimal fluid balance.

demonstrates the relationship between duration and target fluid replacement for steady-state exercise. However, as shown in , some of the most common sports involve supramaximal exercise in short bursts with longer breaks. In this case, individuals should regard an overall average of exercise intensity rather than the maximal effort during the exercise bout when determining optimal fluid balance.

Target fluid replacement estimates to prevent >2 ± 1 % body mass (BM) loss as water (i.e., dehydration). The 70 kg athlete in the example would need to drink a volume of fluid equal to 2.6 ± 0.7 L to prevent >2 ± 1% dehydration when losing 4 L of body water, such as during a marathon (42.1 km). During shorter distances such as 5 or 10 km when fluid losses are unlikely to reach or exceed 2% dehydration, the same athlete would not need to ingest fluids during competition as fluid losses accumulate to <2% dehydration.

It should also be noted that exercise intensity influences gastric emptying rate [37]. Individuals striving to closely match sweat losses with fluid consumption can be challenged by maximal gastric emptying rates. However, when vigorous exercise is conducted (>70% VO2max), gastric emptying decreases predictably, most likely based on decreased splanchnic perfusion [37].

Individuals striving to closely match sweat losses with fluid consumption can be challenged by maximal gastric emptying rates. However, when vigorous exercise is conducted (>70% VO2max), gastric emptying decreases predictably, most likely based on decreased splanchnic perfusion [37].

Practical Solutions:

(1)

Increased fluid intake is necessary with prolonged or intense exercise due to increased sweat production.

(2)

During vigorous exercise (>70% VO2max) understand that gastric emptying may limit fluid absorption. Athletes can train their gut to improve gastrointestinal comfort or adopt strategies to increase fluid intake before and after exercise.

4. Environment

At a fixed exercise intensity, the ambient environment further modulates sweat rate. The magnitude of evaporative, radiant, convective and conductive heat exchange between the body and the environment is a function of the gradients between the environment and the skin which provides the main physiological interface for heat exchange. A number of factors contribute to sweat rate including ambient and radiant temperature, humidity, clothing, and air velocity [34], all of which differ depending on the sport or activity ( and ). Therefore, individuals exercising in hot-humid environments with direct sunlight and minimal airflow will produce near maximal sweat rates and be at the greatest risk of hypohydration. Wet-bulb globe thermometry (WBGT) accounts for these environmental factors and can help inform fluid replacement decisions [38].

A number of factors contribute to sweat rate including ambient and radiant temperature, humidity, clothing, and air velocity [34], all of which differ depending on the sport or activity ( and ). Therefore, individuals exercising in hot-humid environments with direct sunlight and minimal airflow will produce near maximal sweat rates and be at the greatest risk of hypohydration. Wet-bulb globe thermometry (WBGT) accounts for these environmental factors and can help inform fluid replacement decisions [38].

All clothing provides insulation and presents a barrier to heat loss, resulting in increased sweat rates to provide similar cooling to an unclothed situation [34]. Thus, sports/activities with specific clothing requirements, such as American football [39,40], are at greater risk of body fluid loss compared to similar activities in which clothing is minimal. Synthetic wicking materials can increase sweat fluid losses compared to cotton garments [41], potentially decreasing the thermal load but increasing the risk of dehydration. When the effects of hot, humid environmental conditions are combined with clothing and equipment, individuals can achieve near maximal sweat rates which can create a significant fluid deficit rapidly [40].

When the effects of hot, humid environmental conditions are combined with clothing and equipment, individuals can achieve near maximal sweat rates which can create a significant fluid deficit rapidly [40].

Other Environmental Considerations:

Exercising in the cold, or at high altitudes merits special considerations when determining the fluid needs of athletes. Athletes must also be vigilant and mindful of their fluid needs during exercise in the cold. Exercise in the cold can still produce copious sweating, especially when heavy clothing is worn, while also diminishing thirst sensitivity and reducing ad libitum fluid consumption, thus potentially leading to impaired fluid replacement and hypohydration [42]. If possible, athletes should know their individual fluid replacement needs, based upon sweat rate measurement, during exercise in hot and cold environments to ensure they can develop a plan for competing while optimally hydrated.

Athletes unaccustomed to exercising in higher altitudes may require additional fluids. Very high altitude (4900–7600 m) exposure tends to increase water and electrolyte losses, decrease plasma volume and total body water content [43]. In both cold air and high altitudes, respiratory water losses may increase and require additional fluid consumption due to low air water vapor pressures [44]. Therefore, athletes should acclimate to altitude over several days and maintain euhydration prior to competition to ensure optimal athletic performance.

Very high altitude (4900–7600 m) exposure tends to increase water and electrolyte losses, decrease plasma volume and total body water content [43]. In both cold air and high altitudes, respiratory water losses may increase and require additional fluid consumption due to low air water vapor pressures [44]. Therefore, athletes should acclimate to altitude over several days and maintain euhydration prior to competition to ensure optimal athletic performance.

and summarizes typical environmental conditions found among a range of sports into three distinct categories, and how these conditions contribute to the considerations around an individualized fluid plan. Of course, there are large regional differences in environmental conditions experienced for sports at the same time of year [45]. Local measurements utilizing WBGT allow for the greatest characterization of the environmental demands placed on athletes during exercise in the heat [46].

Practical Solutions:

(1)

Measure local environmental conditions to determine the risk of high sweat rates resulting in large fluid losses.

(2)

Increase fluid-replacement during exercise in hot and humid environments to account for increased sweat losses.

(3)

Account for clothing or equipment requirements when evaluating fluid needs.

(4)

Modify fluid intake when exercising in cold or altitude according to an estimation of fluid losses noting that thirst may be less reliable as a guide to dehydration under these conditions.

5. Fluid Availability

Fluid availability refers to the factors that dictate an athlete’s ability to replace fluid losses during activity. In many instances, the characteristics of the sport have a strong influence on the ability to drink during competition and in many scenarios prevent an athlete from “drinking to thirst” [21]. Meanwhile, training activities are often easily modified to allow for some degree of fluid replacement. In many instances, water-breaks during training can be determined on the basis of work-to-rest ratios set by environmental conditions with free access to fluid throughout the break [47]. Characteristics such as flavor and temperature affect the palatability of fluids and may increase voluntary intake when they are matched to the cultural preferences of the athletes and the prevailing conditions (e.g., cool drinks in a warm environment) [48,49].

Characteristics such as flavor and temperature affect the palatability of fluids and may increase voluntary intake when they are matched to the cultural preferences of the athletes and the prevailing conditions (e.g., cool drinks in a warm environment) [48,49].

In endurance sports which provide competitors with feed zones/water stations (e.g., running events), the number of water stations on a course and the frequency with which a competitor reaches them can influence drinking behavior. The International Association of Athletics Federations recommends that stations are placed approximately every 5 km, however, many races include more frequent stations which may influence athletes’ drinking strategies and behaviors [50]. Slower athletes with lower sweat rates who compete in such events, particularly over prolonged distances or duration, are often able to drink in volumes that exceed their true fluid losses and are at particular risk of developing hyponatremia [51]. Athletes taking part in these events should be educated on the importance of fluid balance and the prevention of hyperhydration. It should also be noted that in many events lasting up to 45 min, the risk of dehydration is low due to the limited duration across which sweat losses can accumulate. For faster and/or more competitive athletes, extra elements related to drinking while performing continuous exercise must be taken into consideration. This includes considerations around gastrointestinal comfort when fluid consumed during higher-intensity and “gut joggling” activities (e.g., high-speed running vs. the more “gliding” movements of cross-country skiing or cycling). Furthermore, the time lost in slowing down or moving out of an aerodynamic position to obtain or consume a drink must be factored into the overall race performance. This creates different factors in the cost:benefit analysis of an individual’s fluid intake plan.

It should also be noted that in many events lasting up to 45 min, the risk of dehydration is low due to the limited duration across which sweat losses can accumulate. For faster and/or more competitive athletes, extra elements related to drinking while performing continuous exercise must be taken into consideration. This includes considerations around gastrointestinal comfort when fluid consumed during higher-intensity and “gut joggling” activities (e.g., high-speed running vs. the more “gliding” movements of cross-country skiing or cycling). Furthermore, the time lost in slowing down or moving out of an aerodynamic position to obtain or consume a drink must be factored into the overall race performance. This creates different factors in the cost:benefit analysis of an individual’s fluid intake plan.

The official rules and competition characteristics of “stop-start” sports such as team and racket sports create other influences, and often unique scenarios, around fluid availability. In some examples (e.g., soccer, rugby), governing rules limit the availability of fluids for athletes during competition. Soccer, for example, includes two 45-min halves (with a continuous running clock) in which fluid availability is extremely limited to players. At the other end of the spectrum are sports such as baseball, basketball and tennis with frequent rest breaks within playing time (e.g., time outs, change of ends or player rotations) during which fluids can be consumed. An athlete’s drinking strategy for a competition represents a unique instance for their particular sport based on their ability to rehydrate within the rules [52]. We support recent governing body rule changes and referee decisions to add breaks to competitions (Major League Soccer, FIFA soccer matches, US Open Tennis) to facilitate safe participation by the athletes. These changes likely augment athletic performance and safety simultaneously. Individuals should understand their sport and its fluid needs/fluid availability characteristics to prepare and practice optimal fluid plans for competition.

In some examples (e.g., soccer, rugby), governing rules limit the availability of fluids for athletes during competition. Soccer, for example, includes two 45-min halves (with a continuous running clock) in which fluid availability is extremely limited to players. At the other end of the spectrum are sports such as baseball, basketball and tennis with frequent rest breaks within playing time (e.g., time outs, change of ends or player rotations) during which fluids can be consumed. An athlete’s drinking strategy for a competition represents a unique instance for their particular sport based on their ability to rehydrate within the rules [52]. We support recent governing body rule changes and referee decisions to add breaks to competitions (Major League Soccer, FIFA soccer matches, US Open Tennis) to facilitate safe participation by the athletes. These changes likely augment athletic performance and safety simultaneously. Individuals should understand their sport and its fluid needs/fluid availability characteristics to prepare and practice optimal fluid plans for competition. Where rule changes, or alterations are allowed, individuals and teams should attempt to ask for these alterations (e.g., extended rest periods, additional breaks) in advance to formulate an appropriate drinking strategy. In all sports, athletes should aim to practice and fine-tune their personal drinking strategy for race/competition conditions. This will help individuals to confirm its feasibility, understand their personal responses and develop any necessary behavioral practices within the expected rules of competition.

Where rule changes, or alterations are allowed, individuals and teams should attempt to ask for these alterations (e.g., extended rest periods, additional breaks) in advance to formulate an appropriate drinking strategy. In all sports, athletes should aim to practice and fine-tune their personal drinking strategy for race/competition conditions. This will help individuals to confirm its feasibility, understand their personal responses and develop any necessary behavioral practices within the expected rules of competition.

In and , we define fluid availability into three distinct categories, based on particular sport variations. Sports were categorized as having high fluid availability if there are multiple opportunities for fluid consumption, rather than only during breaks. Low fluid availability was used to describe those activities involving governing rules, time constraints, or an inability to carry personal fluids during competition. Accessibility to fluid consumption during competition represents a major variable to be used in preparation of an optimal fluid replacement strategy.

Practical Solutions:

(1)

During training, ensure that there is ample access to fluids that are palatable to athletes.

(2)

Investigate or understand the opportunities for fluid intake during that are specific to a sport or event, and any other practical issues that determine fluid intake.

(3)

Consider the risks of hyperhydration as well as hypohydration for any sporting event or individual athlete, and prepare appropriate practice and education strategies.

(4)

Develop personalized fluid intake plans that incorporate fluid availability characteristics of the sport or event. Where there is a likelihood of hypohydration, be proactive and creative in making use of existing opportunities for fluid intake within sport rules and characteristics and be prepared to request for changes when there is a likelihood of a serious mismatch between fluid losses and the opportunity to address these.

(5)

Practice intended competition drinking plans ahead of time to determine their suitability and allow time for readjustment.

6. Intrinsic Factors

A number of intrinsic factors modulate the individual variances that are observed in fluid losses. One of the greatest considerations for an individual’s sweat rate is his or her body size. Larger individuals typically have higher sweat losses, with football linemen exhibiting some of the highest recorded sweat rates [14]. Therefore, required absolute drink volumes will be higher for these athletes. An individual’s thirst drive also dictates how much they desire to drink during exercise, but this may not match their actual fluid needs. Indeed, multiple authors report that athletes voluntarily dehydrate during exercise due to discrepancies in fluid losses and drinking behavior [53,54]. Case studies of individuals who have developed hyponatremia due to excessive drinking during exercise also note that they reported thirst as an underlying contributor to their fluid intake [55].

Heat acclimatization contributes to variations in an individual’s sweating rate responses. Individuals who are heat acclimatized exhibit greater sweat rates which can pose a greater risk of hypohydration [56]. Although the increased sweat provides extra heat dissipation, it also requires extra fluid intake.

Individuals who are heat acclimatized exhibit greater sweat rates which can pose a greater risk of hypohydration [56]. Although the increased sweat provides extra heat dissipation, it also requires extra fluid intake.

Women may be at greater risk for exercise-induced hyponatremia. This risk has been attributed to their lower body weight and size, excess water ingestion, and longer racing times relative to men [57]. The greater incidence of hyponatremia in women is unlikely due to their greater levels of estradiol in plasma and tissue. Although female sex-hormones can also influence neural and hormonal control of thirst, fluid intake, sodium appetite and sodium regulation [58,59], there is no evidence that anything beyond stature and drinking behavior significantly impact their risk.

Practical Solutions:

7. Sport-Specific Factors

Weight Division, Acrobatic and Appearance-Based Sports

The culture and normal behaviors surrounding specific sports can greatly affect the hydration practices of its athletes. The three most prominent examples of the cultural effects of sports on hydration practices are weight division sports, acrobatic sports and appearance-based sports. In weight division sports (e.g., combat sports, horse racing, lightweight rowing, etc.), the practice of deliberately dehydrating to manipulate body mass to meet lighter competition weight classifications is common [60]. In many cases, athletes not only sacrifice their performance through these practices but also endanger their health and well-being. In a similar fashion, sports where body-image and appearance are emphasized (e.g., cheerleading, body building and gymnastics), dangerous practices, such as extreme fluid restriction may be used by athletes to cheat “unofficial” weight checks that are self-instigated or expected within their training environment. Finally, “acrobatic” feats such as gymnastics, jumping and climbing are aided by a high power to weight ratio, but should not rely on severe hypohydration to achieve this.

The three most prominent examples of the cultural effects of sports on hydration practices are weight division sports, acrobatic sports and appearance-based sports. In weight division sports (e.g., combat sports, horse racing, lightweight rowing, etc.), the practice of deliberately dehydrating to manipulate body mass to meet lighter competition weight classifications is common [60]. In many cases, athletes not only sacrifice their performance through these practices but also endanger their health and well-being. In a similar fashion, sports where body-image and appearance are emphasized (e.g., cheerleading, body building and gymnastics), dangerous practices, such as extreme fluid restriction may be used by athletes to cheat “unofficial” weight checks that are self-instigated or expected within their training environment. Finally, “acrobatic” feats such as gymnastics, jumping and climbing are aided by a high power to weight ratio, but should not rely on severe hypohydration to achieve this. Excessive use of dehydration to manage body mass goals should be corrected to avoid long-term health complications [61].

Excessive use of dehydration to manage body mass goals should be corrected to avoid long-term health complications [61].

Practical Solutions:

8. Conclusions

Based on the factors in the above sections, along with published literature on typical fluid balance observations in various sports [62,63], we assigned risks of hypohydration to the sports in and . These determinations can be used as a general guideline for sports that pose large risks for fluid imbalances that may limit sport performance. The factors for individual situations or geographical locations may vary and should be considered based on the principles mentioned above to tailor the necessary fluid replacement accommodations. An example of using this paradigm to develop a hydration plan can be found in .

Table 3

Establishing a Hydration Plan.

| Guiding Question | Steps to Correct | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Are athletes in a state of optimal hydration? | ||

| Is the exercise prolonged or intense? | ||

| Is the exercise being performed in environmental conditions that lead to greater fluid losses? | ||

| Is fluid available throughout the entire duration of exercise? |

| |

| Are there individuals with intrinsic risk factors? |

| |

| Are there sport-specific factors that need to be considered? |

In this paper we present a paradigm that can be used by clinicians and practitioners to develop hydration strategies for sports based on fluid availability, environment and exercise intensity. These tools are provided to inform hydration education and practices in a dynamic and individualized manner so that athletes can adapt to different circumstances and optimize performance.

These tools are provided to inform hydration education and practices in a dynamic and individualized manner so that athletes can adapt to different circumstances and optimize performance.

Author Contributions

All authors attended the meeting and contributed to drafting and revision of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the paper.

Funding

The meeting preceding this manuscript was funded by PepsiCo (Gatorade).

Conflicts of Interest

Douglas Casa is the Chief Executive Officer of the Korey Stringer Institute, a 503.c not for profit which subsists on the donations from our corporate partners who include Gatorade, CamelBak, NFL, NATA, Mission, Eagle Pharmaceuticals and Kestrel. He has also been a recipient of grant funds from the following entities to study hydration related products: GE Healthcare, Halo Wearables, Nix Inc., CamelBak. William Adams has consulted with the following entities regarding hydration and exercise performance or the development of hydration assessment devices: BSX Athletics; Samsung Oak Holdings, Inc; Nobo, Inc; Clif Bar &Company; The Gatorade Company, Inc. Lawrence Armstrong is a hydration consultant to Danone Nutricia Research, France and the Drinking Water Research Foundation, Alexandria VA, USA. Lindsay Baker is employed by the Gatorade Sports Science Institute, a division of PepsiCo, Inc. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of PepsiCo, Inc. Louise Burke was a member of the Gatorade Sports Science Institute’s Expert Panel from 2014–2015 for which her workplace received an honorarium. Jose Gonzalez-Alonso was a member of the Gatorade Sports Science Institute’s Expert Panel in 2017 for which his workplace received an honorarium. Stavros Kavouras has served as scientific consultant for Quest Diagnostics, Standard Process and Danone Research and has active grants with Danone Research. The funders had no role in the in the writing of the manuscript.

Lawrence Armstrong is a hydration consultant to Danone Nutricia Research, France and the Drinking Water Research Foundation, Alexandria VA, USA. Lindsay Baker is employed by the Gatorade Sports Science Institute, a division of PepsiCo, Inc. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of PepsiCo, Inc. Louise Burke was a member of the Gatorade Sports Science Institute’s Expert Panel from 2014–2015 for which her workplace received an honorarium. Jose Gonzalez-Alonso was a member of the Gatorade Sports Science Institute’s Expert Panel in 2017 for which his workplace received an honorarium. Stavros Kavouras has served as scientific consultant for Quest Diagnostics, Standard Process and Danone Research and has active grants with Danone Research. The funders had no role in the in the writing of the manuscript.

References

1. Sawka M., Pandolf K.B. Effects of body water loss on physiological function and exercise performance. In: Gisolfi C., Lamb D.R., editors. Perspectives in Exercise Science and Sports Medicine. Volume 3. Benchmark Press; Carmel, CA, USA: 1990. pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]2. Sawka M.N., Wenger C.B., Pandolf K.B. Thermoregulatory Responses to Acute Exercise-Heat Stress and Heat Acclimation. In: Terjung R., editor. Comprehensive Physiology. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2011. pp. 97–151. [Google Scholar]3. Montain S.J., Coyle E.F. Influence of graded dehydration on hyperthermia and cardiovascular drift during exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 1992;73:1340–1350. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.73.4.1340. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]4. Montain S.J., Sawka M.N., Latzka W.A., Valeri C.R. Thermal and cardiovascular strain from hypohydration: Influence of exercise intensity. Int. J. Sports Med. 1998;19:87–91. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-971887. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]5. Sawka M.N., Young A.J., Francesconi R.P., Muza S.R., Pandolf K.B. Thermoregulatory and blood responses during exercise at graded hypohydration levels.

In: Gisolfi C., Lamb D.R., editors. Perspectives in Exercise Science and Sports Medicine. Volume 3. Benchmark Press; Carmel, CA, USA: 1990. pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]2. Sawka M.N., Wenger C.B., Pandolf K.B. Thermoregulatory Responses to Acute Exercise-Heat Stress and Heat Acclimation. In: Terjung R., editor. Comprehensive Physiology. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2011. pp. 97–151. [Google Scholar]3. Montain S.J., Coyle E.F. Influence of graded dehydration on hyperthermia and cardiovascular drift during exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 1992;73:1340–1350. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.73.4.1340. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]4. Montain S.J., Sawka M.N., Latzka W.A., Valeri C.R. Thermal and cardiovascular strain from hypohydration: Influence of exercise intensity. Int. J. Sports Med. 1998;19:87–91. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-971887. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]5. Sawka M.N., Young A.J., Francesconi R.P., Muza S.R., Pandolf K.B. Thermoregulatory and blood responses during exercise at graded hypohydration levels. J. Appl. Physiol. 1985;59:1394–1401. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1985.59.5.1394. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]6. Adams W.M., Ferraro E.M., Huggins R.A., Casa D.J. Influence of body mass loss on changes in heart rate during exercise in the heat: A systematic review. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2014;28:2380–2389. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000501. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]7. Kenefick R.W., Cheuvront S.N. Physiological adjustments to hypohydration: Impact on thermoregulation. Auton. Neurosci. 2016;196:47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2016.02.003. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]8. Trangmar S.J., Gonzalez-Alonso J. New Insights into the Impact of Dehydration on Blood Flow and Metabolism during Exercise. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2017;45:146–153. doi: 10.1249/JES.0000000000000109. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]9. Gonzalez-Alonso J., Crandall C.G., Johnson J.M. The cardiovascular challenge of exercising in the heat. J. Physiol. 2008;586:45–53. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.142158. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]10.

J. Appl. Physiol. 1985;59:1394–1401. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1985.59.5.1394. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]6. Adams W.M., Ferraro E.M., Huggins R.A., Casa D.J. Influence of body mass loss on changes in heart rate during exercise in the heat: A systematic review. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2014;28:2380–2389. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000501. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]7. Kenefick R.W., Cheuvront S.N. Physiological adjustments to hypohydration: Impact on thermoregulation. Auton. Neurosci. 2016;196:47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2016.02.003. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]8. Trangmar S.J., Gonzalez-Alonso J. New Insights into the Impact of Dehydration on Blood Flow and Metabolism during Exercise. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2017;45:146–153. doi: 10.1249/JES.0000000000000109. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]9. Gonzalez-Alonso J., Crandall C.G., Johnson J.M. The cardiovascular challenge of exercising in the heat. J. Physiol. 2008;586:45–53. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.142158. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]10. Trangmar S.J., Gonzalez-Alonso J. Heat, Hydration and the Human Brain, Heart and Skeletal Muscles. Sports Med. 2019;49:69–85. doi: 10.1007/s40279-018-1033-y. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]11. Cheuvront S.N., Carter R., 3rd, Sawka M.N. Fluid balance and endurance exercise performance. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 2003;2:202–208. doi: 10.1249/00149619-200308000-00006. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]12. Cheuvront S.N., Kenefick R.W., Montain S.J., Sawka M.N. Mechanisms of aerobic performance impairment with heat stress and dehydration. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010;109:1989–1995. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00367.2010. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]13. Barr S.I. Effects of dehydration on exercise performance. Can. J. Appl. Physiol. 1999;24:164–172. doi: 10.1139/h99-014. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]14. Sawka M.N., Burke L.M., Eichner E.R., Maughan R.J., Montain S.J., Stachenfeld N.S. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and fluid replacement.

Trangmar S.J., Gonzalez-Alonso J. Heat, Hydration and the Human Brain, Heart and Skeletal Muscles. Sports Med. 2019;49:69–85. doi: 10.1007/s40279-018-1033-y. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]11. Cheuvront S.N., Carter R., 3rd, Sawka M.N. Fluid balance and endurance exercise performance. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 2003;2:202–208. doi: 10.1249/00149619-200308000-00006. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]12. Cheuvront S.N., Kenefick R.W., Montain S.J., Sawka M.N. Mechanisms of aerobic performance impairment with heat stress and dehydration. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010;109:1989–1995. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00367.2010. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]13. Barr S.I. Effects of dehydration on exercise performance. Can. J. Appl. Physiol. 1999;24:164–172. doi: 10.1139/h99-014. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]14. Sawka M.N., Burke L.M., Eichner E.R., Maughan R.J., Montain S.J., Stachenfeld N.S. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and fluid replacement. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2007;39:377–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]15. McDermott B.P., Anderson S.A., Armstrong L.E., Casa D.J., Cheuvront S.N., Cooper L., Kenney W.L., O′Connor F.G., Roberts W.O. National Athletic Trainers′ Association Position Statement: Fluid Replacement for the Physically Active. J. Athl. Train. 2017;52:877–895. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-52.9.02. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]16. Judelson D.A., Maresh C.M., Anderson J.M., Armstrong L.E., Casa D.J., Kraemer W.J., Volek J.S. Hydration and muscular performance: Does fluid balance affect strength, power and high-intensity endurance? Sports Med. 2007;37:907–921. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200737100-00006. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]17. Coyle E.F. Physiological determinants of endurance exercise performance. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 1999;2:181–189. doi: 10.1016/S1440-2440(99)80172-8. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]18. Adams J.D., Sekiguchi Y., Suh H.G., Seal A.D., Sprong C.A., Kirkland T.W., Kavouras S.

Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2007;39:377–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]15. McDermott B.P., Anderson S.A., Armstrong L.E., Casa D.J., Cheuvront S.N., Cooper L., Kenney W.L., O′Connor F.G., Roberts W.O. National Athletic Trainers′ Association Position Statement: Fluid Replacement for the Physically Active. J. Athl. Train. 2017;52:877–895. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-52.9.02. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]16. Judelson D.A., Maresh C.M., Anderson J.M., Armstrong L.E., Casa D.J., Kraemer W.J., Volek J.S. Hydration and muscular performance: Does fluid balance affect strength, power and high-intensity endurance? Sports Med. 2007;37:907–921. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200737100-00006. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]17. Coyle E.F. Physiological determinants of endurance exercise performance. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 1999;2:181–189. doi: 10.1016/S1440-2440(99)80172-8. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]18. Adams J.D., Sekiguchi Y., Suh H.G., Seal A.D., Sprong C.A., Kirkland T.W., Kavouras S. A. Dehydration Impairs Cycling Performance, Independently of Thirst: A Blinded Study. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2018;50:1697–1703. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001597. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]20. Bergeron M.F., Bahr R., Bartsch P., Bourdon L., Calbet J.A.L., Carlsen K.H., Castagna O., González-Alonso J., Lundby C., Maughan R.J., et al. International Olympic Committee consensus statement on thermoregulatory and altitude challenges for high-level athletes. Br. J. Sports Med. 2012;46:770–779. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091296. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]21. Racinais S., Alonso J.M., Coutts A.J., Flouris A.D., Girard O., Gonzalez-Alonso J., Hausswirth C., Jay O., Lee J.K., Mitchell N., et al. Consensus recommendations on training and competing in the heat. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015;49:1164–1173. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-094915. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]22. Carter J.E., Gisolfi C.V. Fluid replacement during and after exercise in the heat. Med.

A. Dehydration Impairs Cycling Performance, Independently of Thirst: A Blinded Study. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2018;50:1697–1703. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001597. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]20. Bergeron M.F., Bahr R., Bartsch P., Bourdon L., Calbet J.A.L., Carlsen K.H., Castagna O., González-Alonso J., Lundby C., Maughan R.J., et al. International Olympic Committee consensus statement on thermoregulatory and altitude challenges for high-level athletes. Br. J. Sports Med. 2012;46:770–779. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091296. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]21. Racinais S., Alonso J.M., Coutts A.J., Flouris A.D., Girard O., Gonzalez-Alonso J., Hausswirth C., Jay O., Lee J.K., Mitchell N., et al. Consensus recommendations on training and competing in the heat. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015;49:1164–1173. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-094915. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]22. Carter J.E., Gisolfi C.V. Fluid replacement during and after exercise in the heat. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1989;21:532–539. doi: 10.1249/00005768-198910000-00007. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]23. Coyle E.F., Hamilton M. Fluid replacement during exercise: Effects on physiological homeostasis and performance. In: Gisolfi C., Lamb D.R., editors. Fluid Homeostasis During Exercise. Volume 3. Benchmark Press; Carmel, CA, USA: 1990. pp. 281–308. [Google Scholar]24. Mora-Rodriguez R., Hamouti N., Del Coso J., Ortega J.F. Fluid ingestion is more effective in preventing hyperthermia in aerobically trained than untrained individuals during exercise in the heat. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2013;38:73–80. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2012-0174. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]25. Wittels P., Gunga H.C., Kirsch K., Kanduth B., Gunther T., Vormann J., Rocker L. Fluid regulation during prolonged physical strain with water and food deprivation in healthy, trained men. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 1996;108:788–794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]26. Armstrong L.E. Hydration assessment techniques. Nutr.

Sci. Sports Exerc. 1989;21:532–539. doi: 10.1249/00005768-198910000-00007. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]23. Coyle E.F., Hamilton M. Fluid replacement during exercise: Effects on physiological homeostasis and performance. In: Gisolfi C., Lamb D.R., editors. Fluid Homeostasis During Exercise. Volume 3. Benchmark Press; Carmel, CA, USA: 1990. pp. 281–308. [Google Scholar]24. Mora-Rodriguez R., Hamouti N., Del Coso J., Ortega J.F. Fluid ingestion is more effective in preventing hyperthermia in aerobically trained than untrained individuals during exercise in the heat. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2013;38:73–80. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2012-0174. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]25. Wittels P., Gunga H.C., Kirsch K., Kanduth B., Gunther T., Vormann J., Rocker L. Fluid regulation during prolonged physical strain with water and food deprivation in healthy, trained men. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 1996;108:788–794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]26. Armstrong L.E. Hydration assessment techniques. Nutr. Rev. 2005;63:S40–S54. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2005.tb00153.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]27. Cheuvront S.N., Kenefick R.W. CORP: Improving the status quo for measuring whole body sweat losses. J. Appl. Physiol. 2017;123:632–636. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00433.2017. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]28. Baker L.B., Lang J.A., Kenney W.L. Change in body mass accurately and reliably predicts change in body water after endurance exercise. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2009;105:959–967. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-0982-0. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]29. Armstrong L.E., Casa D.J. Methods to Evaluate Electrolyte and Water Turnover of Athletes. Athl. Train. Sports Health Care. 2009;1:1–11. doi: 10.3928/19425864-20090625-06. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]30. Cheuvront S.N., Kenefick R.W. Am I Drinking Enough? Yes, No, and Maybe. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2016;35:185–192. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2015.1067872. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]31. Armstrong L.E., Maresh C.M., Castellani J.W., Bergeron M.

Rev. 2005;63:S40–S54. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2005.tb00153.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]27. Cheuvront S.N., Kenefick R.W. CORP: Improving the status quo for measuring whole body sweat losses. J. Appl. Physiol. 2017;123:632–636. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00433.2017. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]28. Baker L.B., Lang J.A., Kenney W.L. Change in body mass accurately and reliably predicts change in body water after endurance exercise. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2009;105:959–967. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-0982-0. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]29. Armstrong L.E., Casa D.J. Methods to Evaluate Electrolyte and Water Turnover of Athletes. Athl. Train. Sports Health Care. 2009;1:1–11. doi: 10.3928/19425864-20090625-06. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]30. Cheuvront S.N., Kenefick R.W. Am I Drinking Enough? Yes, No, and Maybe. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2016;35:185–192. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2015.1067872. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]31. Armstrong L.E., Maresh C.M., Castellani J.W., Bergeron M. F., Kenefick R.W., LaGasse K.E., Riebe D. Urinary indices of hydration status. Int. J. Sport Nutr. 1994;4:265–279. doi: 10.1123/ijsn.4.3.265. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]32. Cheuvront S.N., Sawka M.N. Hydration Assessment of Athletes. Sports Sci. Exch. 2005;18:1–5. [Google Scholar]33. Stolwijk J.A., Saltin B., Gagge A.P. Physiological factors associated with sweating during exercise. Aerosp. Med. 1968;39:1101–1105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]34. Parsons K. Human Thermal Environments: The Effects of Hot, Moderate and Cold Environments on Human Health, Comfort and Performance. 3rd ed. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL, USA: 2014. [Google Scholar]35. Baker L.B., Barnes K.A., Anderson M.L., Passe D.H., Stofan J.R. Normative data for regional sweat sodium concentration and whole-body sweating rate in athletes. J. Sports Sci. 2016;34:358–368. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2015.1055291. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]36. Nadel E.R. Control of sweating rate while exercising in the heat. Med. Sci. Sports.

F., Kenefick R.W., LaGasse K.E., Riebe D. Urinary indices of hydration status. Int. J. Sport Nutr. 1994;4:265–279. doi: 10.1123/ijsn.4.3.265. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]32. Cheuvront S.N., Sawka M.N. Hydration Assessment of Athletes. Sports Sci. Exch. 2005;18:1–5. [Google Scholar]33. Stolwijk J.A., Saltin B., Gagge A.P. Physiological factors associated with sweating during exercise. Aerosp. Med. 1968;39:1101–1105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]34. Parsons K. Human Thermal Environments: The Effects of Hot, Moderate and Cold Environments on Human Health, Comfort and Performance. 3rd ed. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL, USA: 2014. [Google Scholar]35. Baker L.B., Barnes K.A., Anderson M.L., Passe D.H., Stofan J.R. Normative data for regional sweat sodium concentration and whole-body sweating rate in athletes. J. Sports Sci. 2016;34:358–368. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2015.1055291. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]36. Nadel E.R. Control of sweating rate while exercising in the heat. Med. Sci. Sports. 1979;11:31–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]37. Horner K.M., Schubert M.M., Desbrow B., Byrne N.M., King N.A. Acute exercise and gastric emptying: A meta-analysis and implications for appetite control. Sports Med. 2015;45:659–678. doi: 10.1007/s40279-014-0285-4. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]38. Budd G.M. Wet-bulb globe temperature (WBGT)—Its history and its limitations. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 2008;11:20–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2007.07.003. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]39. Kulka T.J., Kenney W.L. Heat balance limits in football uniforms how different uniform ensembles alter the equation. Physician Sportsmed. 2002;30:29–39. doi: 10.3810/psm.2002.07.377. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]40. Armstrong L.E., Johnson E.C., Casa D.J., Ganio M.S., McDermott B.P., Yamamoto L.M., Lopez R.M., Emmanuel H. The American football uniform: Uncompensable heat stress and hyperthermic exhaustion. J. Athl. Train. 2010;45:117–127. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-45.2.117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]41.

1979;11:31–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]37. Horner K.M., Schubert M.M., Desbrow B., Byrne N.M., King N.A. Acute exercise and gastric emptying: A meta-analysis and implications for appetite control. Sports Med. 2015;45:659–678. doi: 10.1007/s40279-014-0285-4. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]38. Budd G.M. Wet-bulb globe temperature (WBGT)—Its history and its limitations. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 2008;11:20–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2007.07.003. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]39. Kulka T.J., Kenney W.L. Heat balance limits in football uniforms how different uniform ensembles alter the equation. Physician Sportsmed. 2002;30:29–39. doi: 10.3810/psm.2002.07.377. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]40. Armstrong L.E., Johnson E.C., Casa D.J., Ganio M.S., McDermott B.P., Yamamoto L.M., Lopez R.M., Emmanuel H. The American football uniform: Uncompensable heat stress and hyperthermic exhaustion. J. Athl. Train. 2010;45:117–127. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-45.2.117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]41. Hooper D.R., Cook B.M., Comstock B.A., Szivak T.K., Flanagan S.D., Looney D.P., DuPont W.H., Kraemer W.J. Synthetic garments enhance comfort, thermoregulatory response, and athletic performance compared with traditional cotton garments. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015;29:700–707. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000783. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]42. O′Brien C., Freund B.J., Sawka M.N., McKay J., Hesslink R.L., Jones T.E. Hydration assessment during cold-weather military field training exercises. Arct. Med. Res. 1996;55:20–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]43. Fusch C., Gfrorer W., Koch C., Thomas A., Grunert A., Moeller H. Water turnover and body composition during long-term exposure to high altitude (4900–7600 m) J. Appl. Physiol. 1996;80:1118–1125. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.80.4.1118. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]44. Mitchell J.W., Nadel E.R., Stolwijk J.A. Respiratory weight losses during exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 1972;32:474–476. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1972.32.4.474. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]45.