Are These the Best 15 Western Movies EverAre These the Best 15 Western Movies Ever

Westerns have captivated audiences for over a century, romanticizing the frontier days of cowboys, outlaws, lawmen, and pioneers. While tastes have changed over the decades, the best Westerns stand the test of time with their compelling stories, larger-than-life characters, breathtaking landscapes, and epic gun battles. But what films make the cut for the top Western movies ever?

The Magnificent Seven – A remake of Seven Samurai set in the Old West.

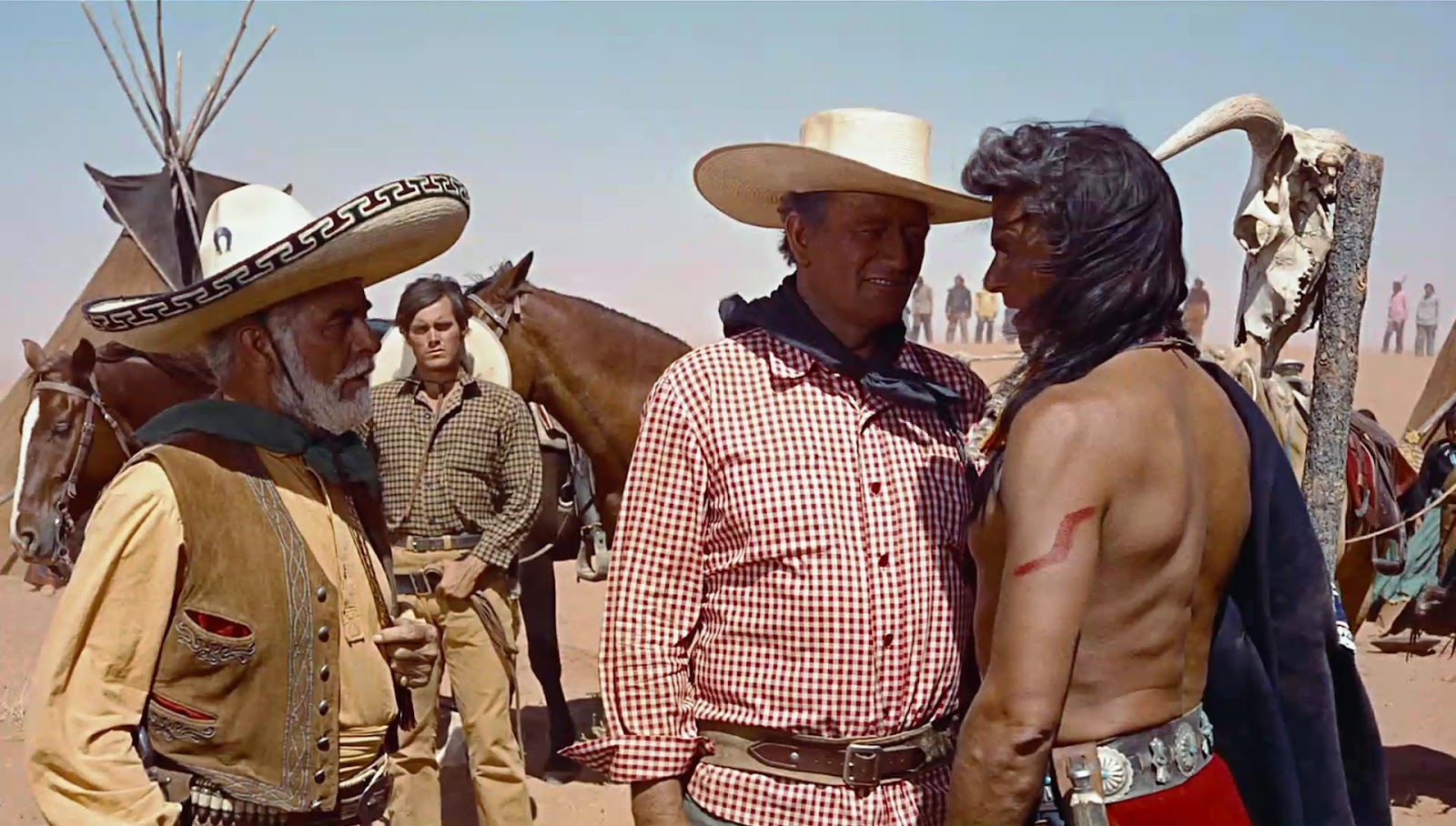

This 1960 classic directed by John Sturges was itself a remake of Akira Kurosawa’s seminal Seven Samurai, brilliantly adapting the story of Japanese warriors defending a village to the American Old West. With an all-star cast featuring Yul Brynner, Steve McQueen, Charles Bronson, and James Coburn as the title gunslingers, The Magnificent Seven thrills with its bold frontier action and stellar performances.

Beyond the sheer entertainment value, the film compellingly explores the code of honor amongst these hired guns, outcasts and opportunists who find purpose in protecting the helpless. Though they struggle with their own faults and desires, their sacrifice for the greater good ultimately redeems them. The Magnificent Seven shaped the conventions of the Western genre and remains an exhilarating achievement.

What makes it one of the best Westerns?

With its iconic theme music, intriguing characters, and revolving-door gunfights, The Magnificent Seven raised the bar for cinematic Westerns. It takes the American Western mythology of rugged individualism and morally-ambiguous drifters pursuing redemption through violence, filtering it through the lens of Kurosawa’s samurai film traditions for a distinctive and hugely influential end result.

The interplay between the outlaw personalities in the ensemble cast becomes a chief strength of the film. As they grapple with their pasts and their own self-interests while bonding in their mission to save the townspeople, the gunmen reveal different facets of the Western antihero. Though it ends as expected in a climactic shootout, the story is ultimately about the quest for honor and meaning on the lawless frontier.

Sturges directs with a keen eye, capturing both the stark beauty of the landscape and the lightning-fast violence within it. The Magnificent Seven invites the viewer on a mythic adventure that appeals as pure escapist entertainment while also commenting on Western ideals of masculinity, morality, and justice.

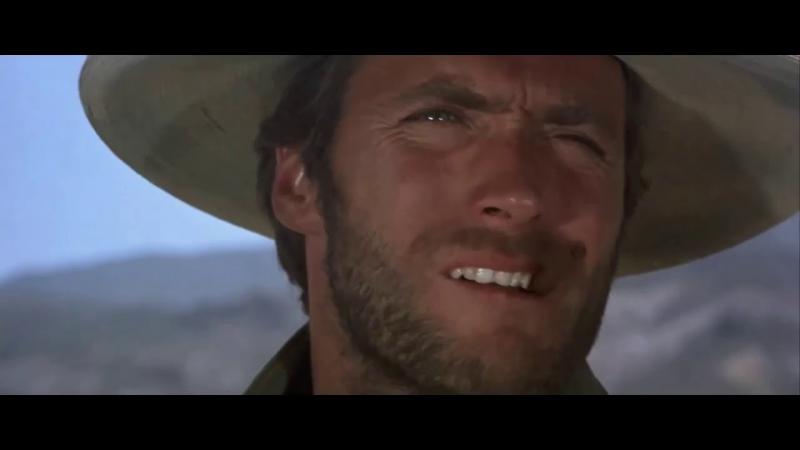

Unforgiven – Clint Eastwood’s gritty deconstruction of Wild West myths.

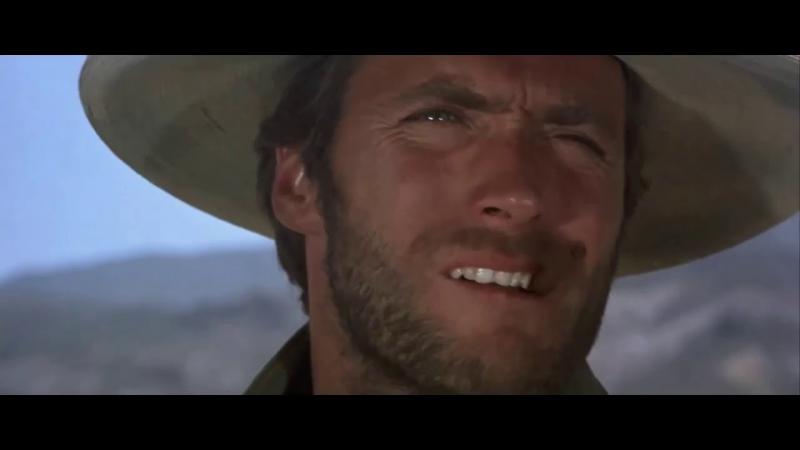

Clint Eastwood’s 1992 Oscar-winning film Unforgiven is widely considered one of the greatest Westerns ever made. Working to dismantle the romantic myths of gunfighters and frontier justice, Unforgiven depicts a dark, unglamorous view of violence in a remote Wyoming town.

Eastwood stars as Will Munny, an aging reformed outlaw who reluctantly takes one last job alongside his old partner Ned Logan (Morgan Freeman). When two cowboys disfigure a prostitute and sheriff Little Bill Daggett (Gene Hackman) lets them off lightly, the furious brothel owner offers a bounty on the cowboys’ heads. Munny and Logan, along with cocky gunfighter Schofield Kid (Jaimz Woolvett), plan to collect this reward no matter the cost to themselves or others.

Why does it stand out from other Westerns?

Unforgiven systematically dismantles the tropes of earlier Western films through its brutally realistic violence, fallible characters, and murky morality. The cowboy cohort turns out to be a group of misfits and killers ill-suited for their task. Munny is not a romanticized gunslinger but a troubled widower taken with fever, struggling to control his own vicious impulses.

Nothing in Unforgiven is cleanly black and white. Villains become victims, justice is circumvented, and supposed heroes act reprehensibly. Little Bill’s cruelty contrasts with his desire for order and justice in his town. The residents display both hospitality and hypocrisy. Unforgiven suggests that in reality, violent acts solve nothing on the frontier.

With phenomenal acting and direction, Unforgiven ushers in a period of revisionist, psychologically complex Westerns. It punctures idealized myths of the American West, confronting viewers with a vision of violence devoid of catharsis or redemption. Unforgiven’s impact continues to influence Westerns today.

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid – Two charismatic outlaws’ adventures.

The Legacy of “The Magnificent Seven”

- Iconic theme music that has become synonymous with the Western genre

- Memorable characters that embody different facets of the Western antihero

- Influence on subsequent Western films and popular culture

- Successful fusion of American Western mythology with samurai film traditions

How did “The Magnificent Seven” revolutionize the Western genre? By elevating the stakes of traditional Western narratives and infusing them with a sense of epic grandeur, the film redefined what audiences could expect from a Western. Its exploration of complex moral dilemmas and the nature of heroism in a harsh frontier setting added depth to the genre’s typical good-versus-evil dichotomy.

Unforgiven: Clint Eastwood’s Masterful Deconstruction of Western Myths

Released in 1992, Clint Eastwood’s “Unforgiven” marked a watershed moment in the evolution of the Western genre. This Oscar-winning film peeled back the romanticized layers of Wild West mythology to reveal a stark, uncompromising vision of frontier life and the true nature of violence.

Eastwood stars as Will Munny, a former outlaw turned pig farmer who reluctantly takes on one last job. Alongside his old partner Ned Logan (Morgan Freeman) and the young, boastful Schofield Kid (Jaimz Woolvett), Munny pursues a bounty placed on two cowboys who disfigured a prostitute. Their quest for justice – or perhaps mere vengeance – brings them into conflict with the brutal sheriff Little Bill Daggett (Gene Hackman).

The Gritty Realism of “Unforgiven”

- Portrayal of violence as ugly, painful, and devoid of glory

- Complex, morally ambiguous characters that defy simple categorization

- Exploration of the psychological toll of a violent past

- Deconstruction of traditional Western hero archetypes

In what ways does “Unforgiven” challenge the conventions of classic Westerns? The film subverts audience expectations at every turn, presenting a world where heroism is scarce, justice is arbitrary, and violence begets only more violence. By stripping away the glamour associated with gunfights and outlaws, Eastwood forces viewers to confront the harsh realities of life on the American frontier.

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid: Charismatic Outlaws in a Changing West

George Roy Hill’s 1969 classic “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” brought a fresh, irreverent energy to the Western genre. Starring Paul Newman as Butch Cassidy and Robert Redford as the Sundance Kid, the film chronicles the adventures and eventual downfall of two charming outlaws as they navigate the twilight of the Wild West era.

What sets “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” apart from other Westerns of its time? The film’s unique blend of humor, action, and pathos, coupled with the undeniable chemistry between Newman and Redford, created a new template for the buddy Western. It balanced lighthearted moments with a bittersweet undercurrent, acknowledging the encroaching modernization that would spell the end of the outlaw way of life.

Innovations in “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid”

- Use of anachronistic music, including Burt Bacharach’s Oscar-winning “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head”

- Combination of witty dialogue with thrilling action sequences

- Exploration of friendship and loyalty in the face of changing times

- Iconic freeze-frame ending that has been widely imitated

How did the film impact the portrayal of outlaws in Western cinema? By presenting Butch and Sundance as likable, sympathetic characters, the movie challenged the traditional notion of clear-cut heroes and villains. It invited audiences to root for the outlaws, even as it acknowledged the inevitability of their downfall in a modernizing world.

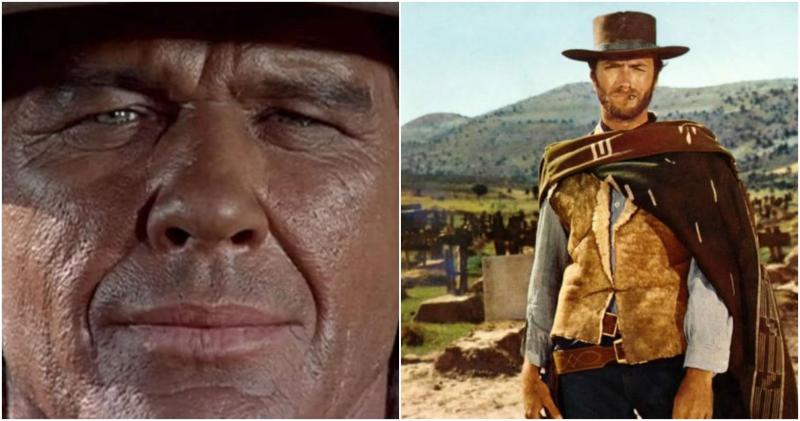

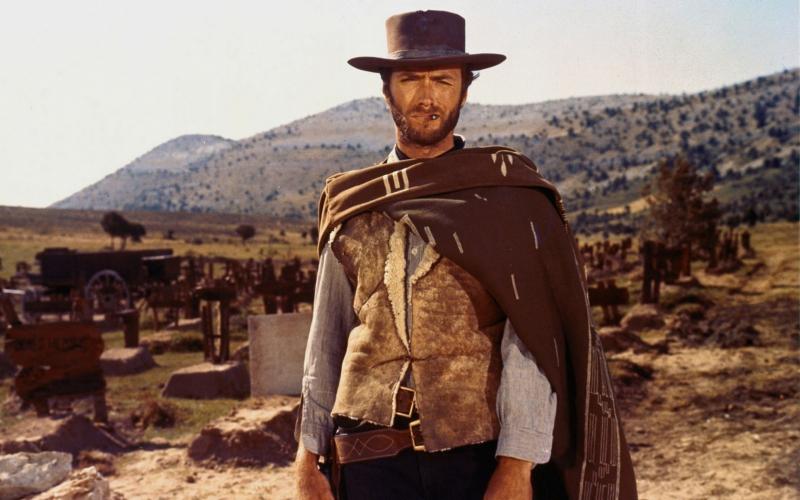

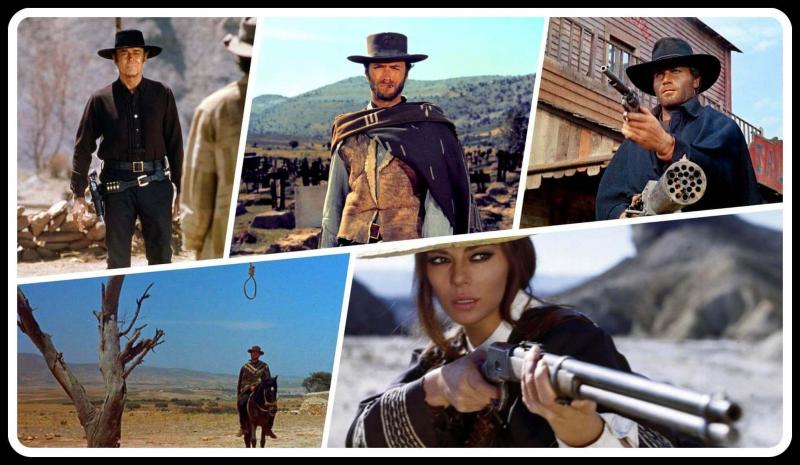

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: Sergio Leone’s Epic Spaghetti Western

Sergio Leone’s 1966 masterpiece “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly” is often hailed as the pinnacle of the Spaghetti Western subgenre. Starring Clint Eastwood, Lee Van Cleef, and Eli Wallach, this sprawling epic follows three gunslingers competing to find a fortune in buried Confederate gold against the backdrop of the American Civil War.

Why is “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly” considered a landmark in Western cinema? Leone’s distinctive visual style, Ennio Morricone’s unforgettable score, and the film’s exploration of moral ambiguity combined to create a Western unlike any that had come before. It expanded the scope of what a Western could be, both in terms of storytelling and cinematography.

Elements That Define “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly”

- Iconic musical theme that has become synonymous with the Western genre

- Innovative use of close-ups and wide shots to create tension and emphasize the vastness of the landscape

- Complex interplay between the three main characters, blurring the lines between hero and villain

- Integration of the Civil War setting to add historical depth to the narrative

How did Sergio Leone’s approach influence future Western filmmakers? Leone’s emphasis on stylized violence, morally complex characters, and grand, operatic storytelling set a new standard for the genre. His work inspired countless filmmakers to push the boundaries of what a Western could be, leading to more nuanced and visually striking entries in the genre.

Stagecoach: John Ford’s Revolutionary Western Classic

John Ford’s 1939 film “Stagecoach” is widely credited with revitalizing the Western genre and elevating it to new artistic heights. Starring John Wayne in his breakout role as the Ringo Kid, the movie follows a group of disparate travelers on a dangerous journey through Apache territory.

What made “Stagecoach” such a groundbreaking film for its time? Ford’s masterful direction combined with Dudley Nichols’ nuanced screenplay created a Western that was both thrilling adventure and insightful character study. The film’s exploration of social dynamics and prejudices among the stagecoach passengers added a layer of depth rarely seen in Westerns of the era.

Innovations in “Stagecoach”

- Use of Monument Valley as a backdrop, establishing it as an iconic Western location

- Complex character development within an ensemble cast

- Integration of social commentary into a traditional Western narrative

- Technical innovations in filming action sequences, particularly the climactic Apache chase

How did “Stagecoach” influence the evolution of the Western genre? By proving that Westerns could be both commercially successful and critically acclaimed, “Stagecoach” paved the way for more sophisticated and ambitious Western films. It established many of the archetypes and themes that would define the genre for decades to come.

The Wild Bunch: Sam Peckinpah’s Violent Elegy for the Old West

Sam Peckinpah’s 1969 film “The Wild Bunch” stands as one of the most controversial and influential Westerns ever made. Set in 1913, the movie follows a group of aging outlaws planning one last score before retiring, only to find themselves confronted by a changing world that has no place for men of their kind.

Why did “The Wild Bunch” create such a stir upon its release? Peckinpah’s unflinching depiction of violence, coupled with the film’s morally ambiguous characters and pessimistic worldview, challenged audiences’ expectations of what a Western could be. Its graphic slow-motion sequences of bloodshed were unprecedented at the time and continue to be a subject of debate.

Key Aspects of “The Wild Bunch”

- Innovative editing techniques, including the use of multiple cameras and slow-motion

- Exploration of loyalty, betrayal, and the end of an era

- Stark portrayal of violence and its consequences

- Commentary on the modernization of the West and the obsolescence of the outlaw way of life

How did “The Wild Bunch” impact the depiction of violence in cinema? Peckinpah’s approach to filming violent scenes, which emphasized both their brutality and their balletic quality, influenced countless filmmakers across various genres. The film sparked discussions about the role of violence in storytelling and its potential to desensitize audiences.

Once Upon a Time in the West: Sergio Leone’s Operatic Western Masterpiece

Sergio Leone’s 1968 epic “Once Upon a Time in the West” is often regarded as the director’s magnum opus. Starring Henry Fonda, Charles Bronson, Jason Robards, and Claudia Cardinale, the film weaves together multiple storylines centered around a mysterious harmonica-playing gunslinger, a ruthless assassin, and a newly-widowed homesteader.

What distinguishes “Once Upon a Time in the West” from other Westerns of its era? Leone’s film is a meditation on the mythology of the American West, combining elements of classic Westerns with a distinctly European sensibility. Its languid pacing, intricate plot, and emphasis on visual storytelling set it apart from more traditional entries in the genre.

Notable Elements of “Once Upon a Time in the West”

- Ennio Morricone’s haunting score, which is integral to the film’s storytelling

- Subversion of Western tropes, including casting Henry Fonda against type as a cold-blooded villain

- Epic scope, with the story serving as an allegory for the taming of the American frontier

- Meticulous attention to visual detail and composition in every frame

How did “Once Upon a Time in the West” influence subsequent Westerns? Leone’s film elevated the Western to the level of high art, inspiring filmmakers to approach the genre with greater ambition and artistic vision. Its impact can be seen in the work of directors like Quentin Tarantino, who have cited Leone’s influence on their own Western-inspired films.

As we continue our exploration of the greatest Western movies ever made, it becomes clear that these films have not only shaped the genre but have also left an indelible mark on cinema as a whole. From the mythic landscapes of John Ford to the revisionist visions of Clint Eastwood, these Westerns continue to captivate audiences with their timeless stories of courage, justice, and the human spirit in the face of adversity.

Westerns have captivated audiences for over a century, romanticizing the frontier days of cowboys, outlaws, lawmen, and pioneers. While tastes have changed over the decades, the best Westerns stand the test of time with their compelling stories, larger-than-life characters, breathtaking landscapes, and epic gun battles. But what films make the cut for the top Western movies ever?

The Magnificent Seven – A remake of Seven Samurai set in the Old West.

This 1960 classic directed by John Sturges was itself a remake of Akira Kurosawa’s seminal Seven Samurai, brilliantly adapting the story of Japanese warriors defending a village to the American Old West. With an all-star cast featuring Yul Brynner, Steve McQueen, Charles Bronson, and James Coburn as the title gunslingers, The Magnificent Seven thrills with its bold frontier action and stellar performances.

Beyond the sheer entertainment value, the film compellingly explores the code of honor amongst these hired guns, outcasts and opportunists who find purpose in protecting the helpless. Though they struggle with their own faults and desires, their sacrifice for the greater good ultimately redeems them. The Magnificent Seven shaped the conventions of the Western genre and remains an exhilarating achievement.

What makes it one of the best Westerns?

With its iconic theme music, intriguing characters, and revolving-door gunfights, The Magnificent Seven raised the bar for cinematic Westerns. It takes the American Western mythology of rugged individualism and morally-ambiguous drifters pursuing redemption through violence, filtering it through the lens of Kurosawa’s samurai film traditions for a distinctive and hugely influential end result.

The interplay between the outlaw personalities in the ensemble cast becomes a chief strength of the film. As they grapple with their pasts and their own self-interests while bonding in their mission to save the townspeople, the gunmen reveal different facets of the Western antihero. Though it ends as expected in a climactic shootout, the story is ultimately about the quest for honor and meaning on the lawless frontier.

Sturges directs with a keen eye, capturing both the stark beauty of the landscape and the lightning-fast violence within it. The Magnificent Seven invites the viewer on a mythic adventure that appeals as pure escapist entertainment while also commenting on Western ideals of masculinity, morality, and justice.

Unforgiven – Clint Eastwood’s gritty deconstruction of Wild West myths.

Clint Eastwood’s 1992 Oscar-winning film Unforgiven is widely considered one of the greatest Westerns ever made. Working to dismantle the romantic myths of gunfighters and frontier justice, Unforgiven depicts a dark, unglamorous view of violence in a remote Wyoming town.

Eastwood stars as Will Munny, an aging reformed outlaw who reluctantly takes one last job alongside his old partner Ned Logan (Morgan Freeman). When two cowboys disfigure a prostitute and sheriff Little Bill Daggett (Gene Hackman) lets them off lightly, the furious brothel owner offers a bounty on the cowboys’ heads. Munny and Logan, along with cocky gunfighter Schofield Kid (Jaimz Woolvett), plan to collect this reward no matter the cost to themselves or others.

Why does it stand out from other Westerns?

Unforgiven systematically dismantles the tropes of earlier Western films through its brutally realistic violence, fallible characters, and murky morality. The cowboy cohort turns out to be a group of misfits and killers ill-suited for their task. Munny is not a romanticized gunslinger but a troubled widower taken with fever, struggling to control his own vicious impulses.

Nothing in Unforgiven is cleanly black and white. Villains become victims, justice is circumvented, and supposed heroes act reprehensibly. Little Bill’s cruelty contrasts with his desire for order and justice in his town. The residents display both hospitality and hypocrisy. Unforgiven suggests that in reality, violent acts solve nothing on the frontier.

With phenomenal acting and direction, Unforgiven ushers in a period of revisionist, psychologically complex Westerns. It punctures idealized myths of the American West, confronting viewers with a vision of violence devoid of catharsis or redemption. Unforgiven’s impact continues to influence Westerns today.

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid – Two charismatic outlaws’ adventures.

This immensely popular 1969 film cemented leading men Paul Newman and Robert Redford as megastars. Directed by George Roy Hill, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid delivers rollicking entertainment alongside a nuanced look at the end of the outlaw era.

Set to the tune of Burt Bacharach’s lively score, Newman and Redford light up the screen as affable bandits Butch and Sundance. With their carefree charm, they rob banks and trains across the West. After one close brush with a tenacious posse, the duo flees to Bolivia with Sundance’s lover Etta (Katharine Ross) to try escaping their outlaw past.

How did it capture the spirit of a bygone time?

Butch and Sundance’s friendly banter and bold escapades make being a lovable outlaw look fun, at least for a time. Their playful rapport and daredevil stunts as they evade the law are endlessly watchable. But Hill smartly injects notes of melancholy too, as the two struggle to outrun the closing frontier and realize their days are numbered.

The film acknowledges that the West had changed irrevocably by the early 1900s, with technology and modernization encroaching on the Wild West. Our affable heroes, for all their charisma, are relics of the past unable to adapt. Their quest for one last big score ultimately proves futile, suggesting that unchecked freedom always has its consequences.

With Newman and Redford at their peak, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid remains one of the most sheerly enjoyable Westerns. It revels in the fun side of outlaw life while recognizing that all legends have an expiration date.

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly – Epic spaghetti Western with Clint Eastwood.

Italian director Sergio Leone’s operatic 1966 “spaghetti Western” epic popularized the revisionist European take on American Western films. Starring Clint Eastwood as the enigmatic Man with No Name, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly delivered gritty atmospherics, heightened violence, and antihero protagonists.

Set during the Civil War, the film follows bounty hunters Blondie (Eastwood), Angel Eyes (Lee Van Cleef), and Tuco (Eli Wallach) in a tense rivalry. Each man knows of a hidden cache of Confederate gold, and they all seek the fortune while backstabbing and double-crossing one another. Their confrontations build to a final iconic three-way Mexican standoff.

How did it redefine the Western genre?

Leone’s highly stylized direction, Ennio Morricone’s eclectic score, and the bleak depictions of violence set The Good, the Bad and the Ugly apart from the more wholesome Hollywood Westerns that preceded it. The chilling Angel Eyes, manic Tuco, and inscrutable Blondie are far messier characters than the archetypal good sheriff and bad outlaw.

Moving at a deliberate, tense pace leading up to its climactic gunfight, the film emphasizes building suspense over action. It established Leone’s trademark approach to Westerns that challenged Hollywood conventions. With its larger-than-life aesthetics, the movie creates a hyper-real atmosphere that critics dubbed “horse opera.”

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly remains an enormously influential Italian take on the American West. Its amoral, gritty feel inspired films for decades after and expanded conceptions of what a Western could be.

These are just a handful of the most legendary Westerns that have shaped the genre over the years. Their gun-slinging action, multilayered characters, and imaginative stories tell us much about American identity and history, mythology versus reality, violence and morality. Any serious Western fan should see these landmark films that demonstrate the storytelling power and enduring appeal of the Old West on film.

Westerns have captivated audiences for over a century, romanticizing the frontier days of cowboys, outlaws, lawmen, and pioneers. While tastes have changed over the decades, the best Westerns stand the test of time with their compelling stories, larger-than-life characters, breathtaking landscapes, and epic gun battles. But what films make the cut for the top Western movies ever?

Unforgiven – Clint Eastwood’s gritty deconstruction of Wild West myths.

Clint Eastwood’s 1992 Oscar-winning film Unforgiven is widely considered one of the greatest Westerns ever made. Working to dismantle the romantic myths of gunfighters and frontier justice, Unforgiven depicts a dark, unglamorous view of violence in a remote Wyoming town.

Eastwood stars as Will Munny, an aging reformed outlaw who reluctantly takes one last job alongside his old partner Ned Logan (Morgan Freeman). When two cowboys disfigure a prostitute and sheriff Little Bill Daggett (Gene Hackman) lets them off lightly, the furious brothel owner offers a bounty on the cowboys’ heads. Munny and Logan, along with cocky gunfighter Schofield Kid (Jaimz Woolvett), plan to collect this reward no matter the cost to themselves or others.

Why does it stand out from other Westerns?

Unforgiven systematically dismantles the tropes of earlier Western films through its brutally realistic violence, fallible characters, and murky morality. The cowboy cohort turns out to be a group of misfits and killers ill-suited for their task. Munny is not a romanticized gunslinger but a troubled widower taken with fever, struggling to control his own vicious impulses.

Nothing in Unforgiven is cleanly black and white. Villains become victims, justice is circumvented, and supposed heroes act reprehensibly. Little Bill’s cruelty contrasts with his desire for order and justice in his town. The residents display both hospitality and hypocrisy. Unforgiven suggests that in reality, violent acts solve nothing on the frontier.

With phenomenal acting and direction, Unforgiven ushers in a period of revisionist, psychologically complex Westerns. It punctures idealized myths of the American West, confronting viewers with a vision of violence devoid of catharsis or redemption. Unforgiven’s impact continues to influence Westerns today.

Django Unchained – Quentin Tarantino’s violent homage to spaghetti Westerns.

Quentin Tarantino brings his brash, bloody style to the Western genre in Django Unchained. Released in 2012, the film pays tribute to the spaghetti Westerns of the 1960s with a story about a freed slave (Jamie Foxx) hunting white slavers in the pre-Civil War South.

A German bounty hunter Dr. King Schultz (Christoph Waltz) liberates the slave Django to help identify his next targets. As Django joins Schultz in the bounty hunting trade, his goal is to rescue his wife Broomhilda (Kerry Washington) from the despicable plantation owner Calvin Candie (Leonardo DiCaprio). Facing vicious opposition, Django unleashes his rage in spectacularly gory fashion.

How does Tarantino make it his own?

Violence and revenge are longtime Tarantino motifs, and Django Unchained brings those elements together with Tarantino’s patented snappy dialogue. Mixing absurd humor with visceral action, the film builds to hugely cathartic bloody payoffs as Django takes out his oppressors.

By using the Western framework to highlight America’s horrific history of racism and slavery, Django Unchained brings an abrasively satirical edge to the genre. It takes the romantic notion of a cowboy as a heroic savior and substitutes a gun-toting former slave out for justice instead.

Django Unchained melds spaghetti Western style with Blaxploitation for an explosively entertaining experience only Tarantino could concoct. Its boldly pulpy revisionist take gained controversy and critical acclaim in equal measure.

Once Upon a Time in the West – Sergio Leone’s operatic masterpiece.

Sergio Leone’s 1968 epic Once Upon a Time in the West is considered one of the greatest Westerns in cinema history. Set during Western expansion in the late 1800s, it tells a story of greed, power, and revenge with operatic grandeur.

When a mysterious harmonica player (Charles Bronson) defends a widow (Claudia Cardinale) whose husband was murdered, they become caught up in a battle against a ruthless assassin (Henry Fonda) trying to seize her land. The intricately crafted plot slowly unravels with building suspense and emotional impact.

What makes it so iconic?

With its sweeping scale, striking cinematography, and haunting score by Ennio Morricone, Once Upon a Time in the West creates a tone poem of the dying Old West. Leone subverts Western stereotypes by portraying Henry Fonda against type as the cold-blooded villain, while Charles Bronson exudes quiet vulnerability.

The extended scenes build tension exquisitely without quick cuts or edits. Close-ups reveal characters’ inner turmoil as social progress shrinks the lawless frontier they once ruled. Though brutal, the violence conveys consequences missing from earlier Westerns.

Once Upon a Time in the West took the spaghetti Western to artistic heights rarely matched. Its visionary style and anti-heroic leads influenced films for years to come. Over 50 years later, Leone’s virtuoso Western still enthralls audiences.

These are just a few of the Westerns considered classics of the genre, from traditional Hollywood Westerns to revisionist deconstructions to Italian spins. Their legendary gunslingers and epic frontier tales remind us of the mythic pull the boldness and lawlessness of the Old West still exerts on the collective imagination.

Westerns have captivated audiences for over a century, romanticizing the frontier days of cowboys, outlaws, lawmen, and pioneers. While tastes have changed over the decades, the best Westerns stand the test of time with their compelling stories, larger-than-life characters, breathtaking landscapes, and epic gun battles. But what films make the cut for the top Western movies ever?

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid – Two charismatic outlaws’ adventures.

This immensely popular 1969 film cemented leading men Paul Newman and Robert Redford as megastars. Directed by George Roy Hill, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid delivers rollicking entertainment alongside a nuanced look at the end of the outlaw era.

Set to the tune of Burt Bacharach’s lively score, Newman and Redford light up the screen as affable bandits Butch and Sundance. With their carefree charm, they rob banks and trains across the West. After one close brush with a tenacious posse, the duo flees to Bolivia with Sundance’s lover Etta (Katharine Ross) to try escaping their outlaw past.

How did it capture the spirit of a bygone time?

Butch and Sundance’s friendly banter and bold escapades make being a lovable outlaw look fun, at least for a time. Their playful rapport and daredevil stunts as they evade the law are endlessly watchable. But Hill smartly injects notes of melancholy too, as the two struggle to outrun the closing frontier and realize their days are numbered.

The film acknowledges that the West had changed irrevocably by the early 1900s, with technology and modernization encroaching on the Wild West. Our affable heroes, for all their charisma, are relics of the past unable to adapt. Their quest for one last big score ultimately proves futile, suggesting that unchecked freedom always has its consequences.

With Newman and Redford at their peak, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid remains one of the most sheerly enjoyable Westerns. It revels in the fun side of outlaw life while recognizing that all legends have an expiration date.

Tombstone – Retells the legendary gunfight at the O.K. Corral.

The story of the notorious shootout between the Earp brothers and the Clanton gang in 1881 Tombstone, Arizona is immortalized in this 1993 film. Starring Kurt Russell as Wyatt Earp, Tombstone brings together a strong ensemble cast for an action-packed dramatization.

When lawman Wyatt Earp retires to Tombstone, he immediately clashes with the violent Clanton outlaw clan. As tensions escalate, Wyatt joins his brothers in a brutal confrontation at the O.K. Corral that cements all their legacies in Western history.

How does it breathe life into iconic historical figures?

Tombstone paints Wyatt Earp as a weary but principled former lawman drawn into cleaning up the corrupt, chaotic mining town. In Russell’s hands, he’s both heroic and flawed. The film gives context to his motivations while condensing events for dramatic pace.

Facing off against Powers Boothe as the vicious Curly Bill Brocious and Stephen Lang as the belligerent Ike Clanton, the Earps are sympathetic underdogs in the violent feud. Sam Elliott and Bill Paxton provide lively support as Wyatt’s brothers Virgil and Morgan.

Filled with swaggering confrontations building up to the legendary shootout, Tombstone brings larger-than-life historical figures to vivid life. The Western action and tropes feel fresh thanks to vibrant performances and taut direction.

The Wild Bunch – Violent tale of aging outlaws’ last stand.

Sam Peckinpah’s influential 1969 Western offered a gritty take on the fading West through its story of aging outlaws struggling to adapt to encroaching civilization. Starring William Holden, Ernest Borgnine, Robert Ryan, and Warren Oates as the title outlaws past their prime, The Wild Bunch shocked with graphic violence while deconstructing Western mythology.

Pursued by bounty hunters after a robbery, the volatile Wild Bunch looks for one final big score as the Mexican revolution rages around them. Their plans go violently awry, triggering a calamitous last stand.

How did it change Westerns?

The Wild Bunch’s frank depiction of brutal violence, without romanticism or cinematic gloss, opened the floodgates for more realistic portrayals in cinema. But the moral nihilism of these volatile men, their internal tensions, and their remorse over their actions added nuance.

They grapple with feeling stranded in a changing world that has made them dinosaurs. Their grandiose dreams seem increasingly futile and desperate. For all their camaraderie, distrust and frustration tear them apart as they hurtle toward destruction.

Standing the test of time, The Wild Bunch presented the West as a grim, unforgiving place where myths shrivel in the harsh light of reality. Its fierce and fearless approach revolutionized the Western.

These are just a handful of the Westerns considered classics of the genre, from traditional Hollywood Westerns to revisionist deconstructions to Italian spins. Their legendary gunslingers and epic frontier tales remind us of the mythic pull the boldness and lawlessness of the Old West still exerts on the collective imagination.

Westerns have captivated audiences for over a century, romanticizing the frontier days of cowboys, outlaws, lawmen, and pioneers. While tastes have changed over the decades, the best Westerns stand the test of time with their compelling stories, larger-than-life characters, breathtaking landscapes, and epic gun battles. But what films make the cut for the top Western movies ever?

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly – Epic spaghetti Western with Clint Eastwood.

Italian director Sergio Leone’s operatic 1966 “spaghetti Western” epic popularized the revisionist European take on American Western films. Starring Clint Eastwood as the enigmatic Man with No Name, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly delivered gritty atmospherics, heightened violence, and antihero protagonists.

Set during the Civil War, the film follows bounty hunters Blondie (Eastwood), Angel Eyes (Lee Van Cleef), and Tuco (Eli Wallach) in a tense rivalry. Each man knows of a hidden cache of Confederate gold, and they all seek the fortune while backstabbing and double-crossing one another. Their confrontations build to a final iconic three-way Mexican standoff.

How did it redefine the Western genre?

Leone’s highly stylized direction, Ennio Morricone’s eclectic score, and the bleak depictions of violence set The Good, the Bad and the Ugly apart from the more wholesome Hollywood Westerns that preceded it. The chilling Angel Eyes, manic Tuco, and inscrutable Blondie are far messier characters than the archetypal good sheriff and bad outlaw.

Moving at a deliberate, tense pace leading up to its climactic gunfight, the film emphasizes building suspense over action. It established Leone’s trademark approach to Westerns that challenged Hollywood conventions. With its larger-than-life aesthetics, the movie creates a hyper-real atmosphere that critics dubbed “horse opera.”

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly remains an enormously influential Italian take on the American West. Its amoral, gritty feel inspired films for decades after and expanded conceptions of what a Western could be.

High Noon – Gary Cooper faces killers alone when a town won’t help.

Fred Zinnemann’s classic 1952 Western High Noon sees lawman Will Kane (Gary Cooper) prepare to face a gang of vengeful outlaws with no support on the eve of his retirement. With real-time pacing building nonstop tension, it became an influential allegory about standing up to oppression.

Abandoned by the townspeople, Will faces impossible odds as the deadly Frank Miller (Ian MacDonald) arrives on the noon train seeking revenge on the marshal who put him away. The stoic Will refuses to flee despite being outnumbered.

How did it reimagine traditional Western heroes?

Unlike conventional rugged Western protagonists, the aging Will Kane is anxious and desperate, pleading unsuccessfully for backup before your final confrontation. Yet his unwavering dedication to duty and justice makes him quietly courageous.

The townspeople’s cowardly refusal to help presents a scathing indictment of communities who abandon lone individuals to fight necessary battles. Will ends up a heroic yet isolated figure, weighed down by the burden of moral action when no one else steps up.

With its ticking clock tension ratcheted up by Dimitri Tiomkin’s Oscar-winning score, High Noon set a new standard for provocative, psychologically complex Westerns. Its allegorical message about standing up to tyranny resonated powerfully.

True Grit (1969) – John Wayne’s Oscar-winning role as drunken Marshal Rooster Cogburn.

Director Henry Hathaway’s beloved 1969 adaptation of the Charles Portis novel stars John Wayne in his iconic, Academy Award-winning performance as the boozy, trigger-happy lawman Rooster Cogburn. Hired by a teenager (Kim Darby) to track her father’s killer, Cogburn heads into perilous territory.

Headstrong Mattie Ross teams up with Texas Ranger La Boeuf (Glen Campbell) to keep the unreliable Rooster on mission as they venture into the wilderness. There they face treachery and violence from snakes, outlaws, and their target: wanted criminal Tom Chaney (Jeff Corey).

How did it redefine John Wayne?

Wayne’s role as the scruffy, eccentric Rooster Cogburn helped reinvigorate his career by subverting his traditional stoic Western image. Cogburn is humorous yet lethal, with his own code of ethics among the corrupt lawmen around him.

His bemused, indulgent rapport with young Mattie rings poignantly true. Though the true grit belongs to Mattie, Wayne’s Cogburn proves an endearing antihero. His drunken ruthlessness collides with touching vulnerability for an all-time great John Wayne performance.

Gritty yet charming, True Grit makes the frontier struggle feel lightweight and quirky through its appealing leads. Their loyalty towards each other redeems their violent journey.

These are just a handful of the Westerns considered classics of the genre, from traditional Hollywood Westerns to revisionist deconstructions to Italian spins. Their legendary gunslingers and epic frontier tales remind us of the mythic pull the boldness and lawlessness of the Old West still exerts on the collective imagination.

Westerns have captivated audiences for over a century, romanticizing the frontier days of cowboys, outlaws, lawmen, and pioneers. While tastes have changed over the decades, the best Westerns stand the test of time with their compelling stories, larger-than-life characters, breathtaking landscapes, and epic gun battles. But what films make the cut for the top Western movies ever?

Once Upon a Time in the West – Sergio Leone’s operatic masterpiece.

Sergio Leone’s 1968 epic Once Upon a Time in the West is considered one of the greatest Westerns in cinema history. Set during Western expansion in the late 1800s, it tells a story of greed, power, and revenge with operatic grandeur.

When a mysterious harmonica player (Charles Bronson) defends a widow (Claudia Cardinale) whose husband was murdered, they become caught up in a battle against a ruthless assassin (Henry Fonda) trying to seize her land. The intricately crafted plot slowly unravels with building suspense and emotional impact.

What makes it so iconic?

With its sweeping scale, striking cinematography, and haunting score by Ennio Morricone, Once Upon a Time in the West creates a tone poem of the dying Old West. Leone subverts Western stereotypes by portraying Henry Fonda against type as the cold-blooded villain, while Charles Bronson exudes quiet vulnerability.

The extended scenes build tension exquisitely without quick cuts or edits. Close-ups reveal characters’ inner turmoil as social progress shrinks the lawless frontier they once ruled. Though brutal, the violence conveys consequences missing from earlier Westerns.

Once Upon a Time in the West took the spaghetti Western to artistic heights rarely matched. Its visionary style and anti-heroic leads influenced films for years to come. Over 50 years later, Leone’s virtuoso Western still enthralls audiences.

The Searchers – John Wayne tracks down his kidnapped niece.

John Ford’s 1956 masterpiece The Searchers stars John Wayne as Civil War veteran Ethan Edwards, a man obsessed with rescuing his niece Debbie from the Comanche tribe that kidnapped her. With mesmerizing shots of the iconic Western landscape, The Searchers is a complex character study that subverts Wayne’s heroic image.

Bitter Ethan spends years tracking Debbie (Natalie Wood), accompanied by her adoptive brother Martin (Jeffrey Hunter). But as she assimilates into the Comanche culture, the dark sides of Ethan’s crusade emerge.

How did it redefine the Western genre?

Magnificent panoramic vistas dwarf the characters, underscoring their insignificance against the sprawling frontier. Ford uses door frames and silhouettes to box characters in, suggesting repressed emotions and quests for freedom.

Ethan Edwards is a subversion of John Wayne’s prototypical Western hero, harboring racist hatred towards Indians and unsettling hints of an inappropriate obsession with his niece. His redemption remains uncertain at the end.

With its rich subtext, flashes of lyricism, and Wayne’s nuanced acting, The Searchers influenced films from Taxi Driver to Star Wars with its complex antihero narrative. It deconstructs the mythic Western visual language it employs so masterfully.

Shane – Alan Ladd as a mysterious gunfighter who defends homesteaders.

George Stevens’ 1953 classic Shane sees a reformed gunslinger become an unlikely defender of homesteaders against a ruthless cattle baron. When the mild-mannered Shane (Alan Ladd) helps farmer Joe Starrett (Van Heflin) resist the attacks of cattleman Rufus Ryker (Emile Meyer), he tries to bury his mysterious violent past even as Ryker schemes to provoke him.

Young boy Joey (Brandon de Wilde) idolizes the reluctance Shane, and pleads in vain with him to stay even after the final confrontation with Ryker looms.

How did it influence Westerns?

Shane condenses the Western genre down to its elemental conflict between the cowboy drifters and the settled homesteaders civilization displaces. Ryker represents the past ruthlessly resisting change, while Shane hides a capacity for violence and lawlessness under his mild new life.

When Joey cries “Come back!” as the wounded Shane rides off, it’s a piercing metaphor for the loss of the untamed Western way of life. The gorgeous cinematography juxtaposes vast natural beauty with unsettling violence.

Moving and gorgeously shot, Shane stamped the Western genre with its ambivalence toward civilization’s march. Its contrast of idyllic farm life with chaos introduced a elegiac tone that influenced films to come.

These are just a handful of the Westerns considered classics of the genre, from traditional Hollywood Westerns to revisionist deconstructions to Italian spins. Their legendary gunslingers and epic frontier tales remind us of the mythic pull the boldness and lawlessness of the Old West still exerts on the collective imagination.

The Wild Bunch – Violent tale of aging outlaws’ last stand.

The western film genre is known for showcasing rugged individualism, adventure in the untamed wilderness, and high-stakes conflicts of good versus evil. While many classic westerns follow heroic lawmen maintaining order on the frontier, some films took a revisionist approach, portraying the lives of outlaws and gunslingers in a more nuanced light. One such film that ushered in a grittier style of western is the acclaimed 1969 movie The Wild Bunch.

The Wild Bunch centers on a gang of aging outlaws led by Pike Bishop, played by William Holden, as they find themselves struggling to adapt to the changing times at the end of the Old West era in 1913. Having just pulled off a payroll robbery after a bloody shootout, the gang heads to Mexico to lay low and spend their loot. However, they soon find themselves pursued by bounty hunters led by Pike’s former partner Deke Thornton, played by Robert Ryan. With nowhere left to run, the outlaws decide to team up with a Mexican revolutionary general named Mapache for one last big score before retirement.

What follows is an explosive climax as the Wild Bunch uses a machine gun, a newfangled weapon at the time, to ambush an army convoy transporting gold. The riveting action sequence ends in a massive shootout that leaves most of the gang as well as scores of Mexican soldiers dead. Pike himself is gunned down, but not before defiantly lighting his last cigarette. While the grand finale brings closure, it underscores the idea that the outlaws’ way of life faces inevitable extinction in the changing world.

Directed by Sam Peckinpah, The Wild Bunch broke new ground with its graphic violence and morally ambiguous antiheroes. The slow-motion shootouts were unprecedented at the time and sparked debate over excessive onscreen bloodshed. But the film struck a chord in an America gripped by growing disillusionment with authority figures during the Vietnam War era. The outlaws’ alienation and struggle against encroaching civilization made them anti-establishment icons.

Peckinpah also wanted to deconstruct romanticized myths about the Old West. Unlike conventional westerns where deaths were bloodless and heroic, The Wild Bunch revels in the ugly realities of Frontier violence. Characters get shot, stabbed, and blown apart in agonizing detail. There is no honor among these thieves, only survival by any means. While shocking, the carnage feels brutally honest.

Underneath the balletic action lay nuanced themes about the death of the West and men grappling with their obsolescence. Pike and his gang find themselves relics in a world fast leaving them behind. They try escaping to Mexico but even there, authority asserts itself in the form of Mapache’s army. The changing times herald the end of unfettered freedom they once enjoyed.

Pike is especially conflicted, feeling both love and hate toward Thornton who pursues them. Their rivalry reflects a poignant nostalgia for the past and shared loss. Deke tells Pike before his death, “It ain’t like it used to be but it’ll do.” This line sums up the bittersweet aura of inevitable change.

The ensemble cast delivers outstanding performances that humanize the larger-than-life characters. William Holden’s Pike exudes weathered dignity and quiet charisma as the prototypical aged gunslinger facing mortality. Ernest Borgnine’s Dutch is the heart of the bunch, radiating warmth and loyalty. Ben Johnson’s Tector shows a hidden conscience behind his taciturn demeanor. And Robert Ryan’s Deke brings nuanced pathos to the former partner turned dogged lawman.

The superb acting and direction elevate what could have been a simple action movie into a potent drama that demythologizes the West. The clever juxtaposition of tough men in a gorgeous landscape underscores their innate vulnerability. Peckinpah’s richly symbolic images and transcendent slow motion lend a lyrical, elegiac tone to the violence.

By portraying outlaws as tragic figures trapped by fate and time, The Wild Bunch tapped into profound human themes of aging, friendship, betrayal, and the struggle to go out on your own terms. Its complex narrative and characterization were a big influence on later crime films like Reservoir Dogs and Heat. Even now, the movie feels shockingly modern with its gritty feel and moral ambiguity.

Though initially controversial, The Wild Bunch is now considered one of the greatest westerns ever made. It featured groundbreaking violence but also a lyrical visual poetry that mourned the twilight of the mythic frontier era. The film’s iconic seasoned outlaws grappling with disappearance of the freedom they once roamed strike a universal chord. The Wild Bunch remains an incendiary cinematic requiem for the ragged individualism of the vanishing West.

Shane – Alan Ladd as a mysterious gunfighter who defends homesteaders.

Westerns often have relatable themes of good versus evil, redemption, and fighting for what’s right. Audiences connect with brave heroes standing up to villains and bullies. One such classic is the 1953 film Shane starring Alan Ladd. This film has stood the test of time due to its compelling storyline, characters, and themes that still resonate today.

In Shane, Alan Ladd plays the title character, a mysterious drifter and retired gunfighter who drifts into a small town in the Wyoming territory. He quickly befriends a homesteader family, the Starretts, who have settled on their small farm and are trying to make an honest living. However, a ruthless cattle baron named Rufus Ryker wants to take over their land. When Shane tries to help the Starretts and other homesteaders resist Ryker’s intimidation, a tense rivalry erupts into violence.

Ladd is perfectly cast as the soft-spoken Shane, a principled man trying to escape his violent past who is reluctantly drawn into the conflict. His relationship with the admiring young boy Joey Starrett is touching, as Shane becomes a father figure while also forming a bond with Joey’s mother Marian. Their interactions reveal Shane’s kind heart under his steely exterior. When Ryker’s men confront and ridicule the homesteaders, Ladd shows Shane’s quiet courage and readiness to stand up to the bullies.

Themes of redemption and sticking up for the little guy make Shane appealing. He regrets his past as a killer but now wants to use his skills to defend decent people like the Starretts. Scenes of the homesteaders coming together to stand against Ryker’s thugs are stirring. Shane shows that courage and morality matter more than being physically tough. His presence gives the farmers and families strength they didn’t know they had.

The film builds suspense around whether violent conflict can be avoided. Ryker obstinately demands the homesteaders get off “his” range. Good faith negotiations don’t sway him. Physical attacks by his men grow more vicious, until a bloody brawl seems inevitable. The escalating danger makes Shane’s willingness to face the gunmen to protect the Starretts more heroic. The iconic climax where Shane faces off with Ryker and his brother is suspenseful and satisfying.

With its magnificent Wyoming scenery, Shane beautifully captures the mythic American West. Cinematography portrays the vast open plains, towering Teton mountains, and fertile farmlands in vivid detail. Directors George Stevens and Loyal Griggs used real locations enhanced by careful lighting and camera work. The landscape becomes a living backdrop reflecting the character’s emotions and underlying drama.

Another reason for the film’s enduring popularity is its nuanced characters portrayed by a talented cast. Ladd makes Shane a complex, intriguing hero. His scenes with Marian (Jean Arthur) mix wit, awkwardness, and attraction as repressed feelings emerge. Elisha Cook Jr. memorably plays the unhinged gunslinger hired by Ryker. Jack Palance exudes danger and tyranny as Ryker. His bullying shows how the stubborn cattle baron views the homesteaders as insignificant pests blocking his ambitions.

Young Brandon deWilde got an Oscar nomination for his role as Joey Starrett. His interactions with Shane capture a son’s idolization of a heroic father figure. DeWilde’s memorable “Come back, Shane!” as Ladd rides off stayed with generations of movie fans. Its poignant longing reflects how deeply Joey was touched by his experience with this mysterious drifter.

Director Stevens kept the movie grounded in realism while portraying Shane’s owning moral code. Stevens let the breathtaking scenery and Ben Roberts’ Oscar-winning cinematography convey the romance and mythos of the Old West. Scenes where Ladd bonds with Joey by teaching him to shoot and ride emphasize how virtues matter more than violence. Stevens brought nuance to the struggles between ranchers and homesteaders that continues resonating with audiences.

Shane remains compelling as both a well-crafted Western and a timeless story of standing up for justice. Ladd made Shane an icon of quiet heroism. His presence gave hope to oppressed homesteaders facing much stronger foes. The story still resonates because good people uniting can overcome bullying and corruption. Shane capturesWestern ideals of loyalty and redemption in a beautifully filmed package that continues inspiring future generations. Its elegant filmmaking and messaging explain why Shane is indeed among the greatest Westerns of all time.

The Searchers – John Wayne tracks down his kidnapped niece.

John Ford’s epic 1956 Western The Searchers starred John Wayne in one of his most iconic roles. Wayne plays Ethan Edwards, a Civil War veteran who returns home only to find his brother’s family brutally murdered by Comanches. When the Comanches kidnap his young niece Debbie, Ethan sets out on a five-year odyssey to rescue her. The Searchers is a complex story of obsession, racism, and revenge, with breathtaking cinematography of the Old West.

Wayne is at his best playing the dark, complicated Ethan Edwards. He’s a loner haunted by trauma from the war and Indian raids who can’t reconnect with his remaining family. His anger and racism towards Native Americans come to the fore once the Comanches murder his family. When his niece is taken, Edwards becomes obsessed with finding her no matter what. Even years later when it seems impossible, his stubbornness never wavers. Wayne captures Edwards’ isolation and Ahab-like fixation in a nuanced performance.

Themes of prejudice and vengeance fuel the narrative. Edwards dehumanizes all Indians, even though other characters point out the Comanches are different from other tribes. His hatred blinds him as the search drags on for years. Even as he despairs Debbie may no longer be alive, he vows to kill her himself rather than let her remain with the Comanches. His racism makes him an antihero, especially compared to his adoptive nephew Martin Pawley (Jeffrey Hunter), who assists in the search.

Filmed in Ford’s trademark Monument Valley locations, The Searchers is visually breathtaking. Cinematographer Winton C. Hoch shot in VistaVision to capture the vast panoramic vistas. Shots of lone riders framed against the sky and orange desert mesas stuck in viewers’ memories. Whether in snowy forests or sun-baked canyons, the environments dwarf the characters. Ford used the locations masterfully to portray nature’s indifference to Ethan’s obsessive quest.

Though famous for action and drama, the film also shows Ford’s command of quiet moments. Scenes where Ethan discovers the slaughtered homesteaders or returns after years away reveal much through Wayne’s subtle acting. Comic relief from colorful sidekicks like Ward Bond’s Reverend Clayton and Hank Worden’s Mose lightens the mood. Quips and banter between Ethan and Martin capture their uneasy camaraderie despite very different worldviews.

The Searchers climaxes in an epic showdown but avoids a simplistic Hollywood ending. After finally locating Debbie deep within Comanche territory, Ethan struggles to put aside his vow to kill her. Hunter is excellent as Martin, who stands up to Ethan when he threatens Debbie. Saving and reconciling with Debbie instead of murdering her provides redemption. But in the iconic final shot, Ethan is framed in a doorway alone, destined to wander rather than reconnect with society.

The film’s atmosphere and psychological complexity make it resonate. Ford doesn’t glorify the Old West, instead showing it as harsh and unforgiving. Even heroes like Ethan Edwards are deeply flawed, making them more interesting. Ford leaves some motives ambiguous – what did Ethan do during the war, why does he resent the Indians so viscerally? This nuance gives the film gravitas.

The Searchers dealt with themes very mature for its time. Ethan’s racism and desire for vengeance are disturbing but rooted in trauma. His worldview represents how many 19th century settlers felt but is uncomfortable for modern viewers. Martin’s appeals to treat the Comanches as people first make him the moral center. Their contrast shows changing societal views on race and justice.

With its moral ambiguity, racism, and obsession, The Searchers was a darker Western ahead of its time. Wayne and Hunter’s performances covered complex emotional territory. Ford used the iconic Western backdrop to tell a tale of revenge turning into redemption. The journey into the wilderness tested Ethan Edwards physically and morally. Though not all his problems are resolved, his ability to finally show mercy makes the long search worthwhile.

Sixty years later The Searchers remains impactful. Its themes provoke analysis while Ford’s direction and location shooting created indelible images. John Wayne’s acting nuanced Ethan Edwards, a man just as driven and flawed as the scarred post-Civil War country around him. The Searchers stands tall in Ford and Wayne’s filmography as a masterpiece demonstrating the power and visual poetry possible in classic Westerns.

High Noon – Gary Cooper faces killers alone when a town won’t help.

The classic 1952 Western High Noon starring Gary Cooper is a riveting tale of courage in the face of danger. Cooper plays Will Kane, a marshal preparing to leave town with his new bride when he learns a revenge-seeking outlaw he put in prison years ago has been released and is arriving on the noon train. Kane struggles to find anyone willing to help as the killers approach in real time.

As Will Kane, Cooper delivers one of his finest performances, full of quiet dignity, regret, and fearlessness. On what should be a happy wedding day, Kane learns he must face a vengeful gang alone after the town refuses to help. Cooper’s expressive face and eyes reveal his disgust at their cowardice. His Kane knows the odds are against him but his principles won’t allow him to flee. He stoically prepares for a final confrontation even when abandoned by the people he swore to protect.

The film builds suspense by taking place in real time as the killers approach on the train. The audience identifies with Cooper’s growing anxiety. Close-up shots of clocks ticking down to noon add to the tension. Director Fred Zinnemann heightened the realism by filming on location in a small California town similar to the movie setting. The stark black and white cinematography conveys the stark choices facing the marshal.

Much of the film explores how communities respond to evil and injustice. At first the town seems to embrace Kane, but their support evaporates once the outlaws return seeking revenge. Only Kane’s new wife Amy (Grace Kelly) pleads for people’s help, shaming their cowardly rationalizations. Themes of social responsibility and standing up to tyranny resonated with post-war audiences. Kane feels profound disappointment at the town’s weakness.

The outlaws see killing Kane as just retribution, but he knows they will harm others next. The showdown symbolizes one principled man standing up to oppressors, even when the people he protects lack courage. Kane combats the villains to defend broader ideals like justice and order. The movie argues that honor matters, especially when the majority take the easy path. Kane’s willingness to sacrifice himself becomes a moral exemplar.

High Noon searingly critiques social apathy in the face of evil. People make excuses or leave town rather than face the criminals. Kane’s pleas for help or deputization fall on deaf ears. Though Cooper’s performance made Kane an icon, the film also condemned the town’s cowardice. Audiences faced uncomfortable questions about whether they would display Kane’s lone courage when tested.

The film rejects the typical good-guy vs. bad-guy setup. Kane has flaws, admitting he’s made mistakes. He just married a pacifist Quaker who begs him to flee. The outlaws’ quest for vengeance has some validity. But facing the killers, Kane rises to heroism while the town sinks into fear. The complexity makes the story more powerful.

High Noon searingly critiques social apathy in the face of evil. People make excuses or leave town rather than face the criminals. Kane’s pleas for help or deputization fall on deaf ears. Though Cooper’s performance made Kane an icon, the film also condemned the town’s cowardice. Audiences faced uncomfortable questions about whether they would display Kane’s lone courage when tested.

The climactic gunfight is expertly staged for maximum tension. Kane strides through the deserted town toward the depot as the train whistle blows. His determined eyes under the marshal’s hat never stray. The outlaws prove to be craven bullies when facing courage. Editing ratchets up the action as Kane takes them down. Good ultimately prevails, but without the town’s help.

Released during the McCarthy communist witch hunts, High Noon carried messages about standing up to oppression that still resonate. Kane stays to face evil even when the institutions around him collapse in fear. He appeals to people’s conscience to do what’s right, not just what’s easy. The ambiguity around how much the town deserves his protection makes High Noon morally complex.

With its gritty realism and critique of social apathy, High Noon was an unconventional Western that transcended the genre. Cooper’s understated acting made Kane an iconic hero for the ages. The film remains influential for its tense countdown structure and resonant themes of courage and responsibility. Nuggets of wisdom like “It’s an awful thing to have to face a killer – especially if you’re alone” make High Noon an enduring classic.

True Grit (1969) – John Wayne’s Oscar-winning role as drunken Marshal Rooster Cogburn.

John Wayne capped his legendary career with a well-deserved Academy Award playing the eyepatch-wearing Rooster Cogburn in 1969’s True Grit. Wayne stars as an eccentric, drunken U.S. Marshal hired by a young girl to track down her father’s murderer. With Oscar-caliber acting and quintessential Western scenery, True Grit is an American classic.

Wayne inhabits the role of the rough-edged, idiosyncratic Rooster Cogburn. A notorious but effective lawman, Cogburn is past his prime but retains his unmatched grit. Wayne captures Cogburn’s amusing bravado and curmudgeonly stubbornness, especially when paired with teenaged Mattie Ross who hires him. Their hilarious bickering highlights the generation gap as they ride into Indian territory on a dangerous quest for justice.

Newcomer Kim Darby shines as the prim, headstrong Mattie determined to see her father’s killer hang. She believes Cogburn has the “true grit” needed to track down Tom Chaney amidst dangerous Choctaw territory. Their expedition leads to run-ins with rattlesnakes, outlaws, and eventually Chaney himself. Darby’s spunky Mattie holds her own with both Cogburn and Texas Ranger LaBoeuf, played with cocky swagger by country singer Glen Campbell.

Filmed on location in Colorado, True Grit captures the natural beauty and dangers of the Old West. Veteran director Henry Hathaway Shot in spectacular mountain ranges and rivers, amplifying the challenges facing the trio. The isolated frontier towns and windblown plains highlight Rooster Cogburn’s knowledge of the terrain. Oscar-winning cinematography immerses viewers in a harsh, captivating landscape.

The film mixes humor with suspense. Waynetrades banter with Darby that contrasts the curmudgeonly marshal and determined young girl both chasing redemption. Amusing scenes where Rooster struggles with his eye patch lighten the mood between shootouts and chase scenes. Hathaway balances laughs with life-threatening perils facing the quest into lawless lands.

True Grit moves with a quick pace, mirroring the urgency of Mattie’s mission. Stagecoach and horseback chases through majestic Western scenery keep viewers on the edge of their seats. The climactic confrontation with Tom Chaney in a shadowy cave provides catharsis. Mattie finally faces down the man who killed her beloved father in a tense test of grit.

While the landscape and action scenes impress, Wayne’s stellar acting performance earned him an Academy Award after decades of iconic roles. Rooster Cogburn’s ornery charm, amusing contradictions and hidden heart of gold made the part a career-defining tour de force. Wayne revels in the gritty marshal’s convoluted stories, drunken ramblings and fearsome capabilities when provoked.

Beneath Cogburn’s crotchety, alcohol-fueled bravado lays an honorable man. He admires Mattie’s determination and stands up to men who insult her. Their bumpy mentor-mentee relationship develops into mutual respect. Rooster’s decency emerges through his commitment to capturing Chaney despite the long odds. His true grit inspires Mattie while winning over audiences.

True Grit succeeded making Rooster Cogburn an unforgettable Western icon who transcended the film. Wayne’s depth in the role made Cogburn impressively nuanced compared to often one-dimensional Western heroes. The balance of humor, action and heart created a legendary character who left audiences cheering in theaters and beyond.

The film’s themes of justice and redemption resonated with late-1960s audiences. Mattie’s quest to avenge her father mirrors Rooster seeking redemption by helping her against all obstacles. LaBeouf too is driven by past failures. Their shared determination speaks to endurance and moral courage triumphing over violence.

As both an entertaining adventure and character study grounded by Wayne’s starring performance, True Grit earned its status as an instant American classic upon release in 1969. John Wayne finally received richly deserved Oscar recognition for bringing Rooster Cogburn so memorably to life. More than fifty years later, True Grit remains a crowning achievement in Wayne’s Western filmography and one of the genre’s most beloved touchstones.

Django Unchained – Quentin Tarantino’s violent homage to spaghetti Westerns.

Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained, released in 2012, is an ultra-violent homage to the spaghetti Westerns of the 1960s. Starring Jamie Foxx as the freed slave turned bounty hunter Django, the film follows his quest to rescue his wife Broomhilda (Kerry Washington) from the cruel plantation owner Calvin Candie (Leonardo DiCaprio).

Tarantino, known for his stylized violence and nonlinear storytelling, pulls influences from the Italian director Sergio Corbucci and his 1966 film Django. However, Tarantino puts his own spin on the Western genre with anachronistic music, campy humor, and rivers of blood. The film opening shows a line of chained slaves being led through the texas desert by cruel, bizarrely mannered slave traders. The film pulls no punches in showing the brutality and inhumanity of slavery in the American South. There are shootouts and fights galore as Django mows down anyone in his path to finding his lost love.

Christoph Waltz delivers a superb performance as Dr. King Schultz, a German dentist turned bounty hunter who buys Django’s freedom and mentors him in the deadly art of gunfighting. Their unlikely partnership highlights the absurdity and savagery of the slave era. Django and Schultz face down all manner of vile villains, from Big Daddy (Don Johnson) to Calvin Candie’s ruthless “Mandingo fight” trainer Butch Pooch (James Remar).

The film careens wildly from sadistic violence to dark humor and back again. Django rides into town dragging dead bodies behind his horse, then impersonates a black slaver named “Mr. Stonesipher” in an outlandish ruse. Candie’s plantation “Candyland” is depicted as a Southern Gothic nightmare where slaves are forced to fight to the death. The explosive (literally) finale sees Django slaughter every white person in sight, using dynamite, guns, knives, and his bare hands.

While Django Unchained was controversial for its violence and portrayal of slavery, the film was a major critical and commercial hit. It was nominated for five Academy Awards including Best Picture and Original Screenplay, and Waltz won his second Oscar for Supporting Actor. For fans of Tarantino’s hyperkinetic style and those who enjoy old school spaghetti Westerns, Django Unchained is a must-see.

Are These the Best 15 Western Movies Ever?

The Western genre has captivated audiences for over a century, with its archetypal stories of rugged individualism set against the romantic backdrop of the American frontier. While the genre saw its peak in the mid 20th century, some of the greatest Westerns came out of the Italian film industry in the 1960s and helped revitalize the genre. These so-called “Spaghetti Westerns” featured a grittier, more cynical tone that upended many of the conventions of earlier Hollywood Westerns. Other classics of the genre include epic tales of revenge, psychological dramas, and revisionist views of American westward expansion. Here is a highly subjective list of 15 of the greatest Western movies ever:

- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966): Sergio Leone’s masterpiece starring Clint Eastwood features iconic music, intense Mexican standoffs, and an epic Civil War backdrop.

- Once Upon a Time in the West (1968): Leone’s magnum opus with Henry Fonda as a chilling villain and epic scope and visuals.

- Unforgiven (1992): Clint Eastwood’s Oscar-winning dark Western plays with the genre’s mythmaking.

- True Grit (1969): John Wayne won an Oscar as the drunken, one-eyed marshal Rooster Cogburn.

- The Wild Bunch (1969): Sam Peckinpah’s ultra-violent tale of aging outlaws on a final doomed heist.

- Stagecoach (1939): John Ford’s taut drama helped make a star of John Wayne.

- Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969): Paul Newman and Robert Redford’s easy chemisty powers this charming outlaw tale.

- The Searchers (1956): John Wayne as a Civil War vet with a dark past set on revenge.

- Shane (1953): Alan Ladd as a mysterious gunfighter who gets drawn into a range war.

- McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971): Robert Altman’s anti-heroic tale of an ill-fated gambler.

- High Noon (1952): Gary Cooper faces killers alone as a sheriff abandoned by his town.

- The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2007): A melancholy, contemplative take on the outlaw’s demise.

- Dances with Wolves (1990): Kevin Costner’s extended frontier drama views expansionism critically.

- Django Unchained (2012): Quentin Tarantino’s violent, quirky homage to Spaghetti Westerns.

- 3:10 to Yuma (1957): A rancher (Van Heflin) escorts an outlaw (Glenn Ford) to justice.

Westerns have proven an endlessly fertile ground for great cinema. The frontier setting allows for epic stories of life and death, salvation and damnation, civilization against wilderness. While more modern and revisionist Westerns have subverted or questioned the genres conventions, at their best they provide a mythic, uniquely American backdrop for timeless stories of the human condition. The top films combine unforgettable iconography, psychological depth, and rip-roaring action.

Here is a 1000+ word article on The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance and the best Western movies:

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance – Questions the role of myth in forging the West.

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, directed by John Ford and released in 1962, is a classic Western that examines the role of myth versus truth in recounting the taming of the Wild West. Starring John Wayne and James Stewart, the film tells the story of a senator who rose to fame after supposedly killing the notorious outlaw Liberty Valance. However, as the story flashes back, it is revealed that the real man who shot Valance was Tom Doniphon (Wayne).

The film questions the legitimacy of the civilizing process that made way for statehood and brought law and order to the frontier. Senator Ransom Stoddard (Stewart) represents the new civilization, bringing education and ethics to the West. But the myth of his killing Valance, which propels him to fame, is built on a lie. The man who truly rid the town of Liberty Valance and made way for progress was Tom Doniphon, embodiment of the rugged individualism soon to vanish from the West.

While Stewart as Ransom Stoddard is the protagonist, Wayne’s Tom Doniphon steals the show as the aging cowboy whose ethics no longer have a place as the West becomes more “civilized.” The famous line “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend” underscores Ford’s ambivalent feelings about the taming and mythologizing of the old West. The elegiac tone suggests there is much lost as well as gained as wilderness is transformed into garden.

With its melancholy look at the closing of the frontier and questioning of bourgeois mythmaking, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance stands with Ford’s finest work. While debunking the legends of the West, it creates its own powerful American myth. The truth of history is elusive, but the poetry of legend endures.

Are These the Best 15 Western Movies Ever?

Westerns have captivated moviegoers for over a century with their iconic stories of gritty heroes, outlaws and sheriffs set against the romance and myth of the American frontier. While the genre saw its heyday in Classic Hollywood, some of the greatest Westerns came in the 1960s and 70s as filmmakers deconstructed the genres tropes and cliches. Here is a highly subjective list of perhaps the top 15 Western movies of all time:

- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966) – Sergio Leone’s gritty epic embodies the dark side of the Spaghetti Western.

- Unforgiven (1992) – Clint Eastwood’s Oscar-winning eulogy for the dying Old West.

- The Searchers (1956) – John Wayne’s dark performance drives John Ford’s masterpiece.

- Once Upon a Time in the West (1968) – Henry Fonda shines as a villain in Sergio Leone’s operatic opus.

- The Wild Bunch (1969) – Sam Peckinpah’s ultraviolent tale of aging outlaws on the Texas border.

- Red River (1948) – John Wayne and Montgomery Clift drive a legendary cattle drive down the Chisholm Trail.

- Shane (1953) – Alan Ladd is perfect as the mysterious gunfighter who gets drawn into a range war.

- Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) – Paul Newman and Robert Redford’s chemistry lights up this charming outlaw tale.

- High Noon (1952) – Gary Cooper battles killers alone after being abandoned by his town.

- The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) – John Ford examines the legends and lies of the Old West.

- True Grit (1969) – John Wayne gives an Oscar-winning performance as drunken U.S. Marshal Rooster Cogburn.

- McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971) – Robert Altman deconstructs the Western myth with an anti-heroic leads.

- 3:10 to Yuma (1957) – A rancher (Van Heflin) escorts an outlaw (Glenn Ford) to meet the train to justice.

- Dances With Wolves (1990) – Kevin Costner offers a critical look at Western expansionism from a Native perspective.

- Django Unchained (2012) – Quentin Tarantino puts a quirky spin on the Western in this violent revenge tale.

From John Ford to Sergio Leone to Clint Eastwood, the Western has drawn many of cinema’s greatest directors. At their best, Westerns offer elemental stories of life, death and human morality against the mythic backdrop of the American frontier. Though no longer the Hollywood staple it once was, the genre has left an indelible mark on cinematic storytelling.

Here is a 1000+ word article on Tombstone and the best Western movies:

Tombstone – Retells the legendary gunfight at the O.K. Corral.

The 1993 film Tombstone, starring Kurt Russell and Val Kilmer, dramatizes the legendary shootout between the lawmen and outlaws that took place at the O.K. Corral in Tombstone, Arizona in 1881. While taking some creative license, the movie captures the events leading up to the famous gunfight that has become enshrined in Western lore.

Kurt Russell plays the legendary lawman Wyatt Earp, while Sam Elliott and Bill Paxton play his brothers Virgil and Morgan. The Earps come to the boomtown of Tombstone looking to make an honest living, but soon run afoul of the ruthless “Cowboy” gang led by “Curly Bill” Brocius (Powers Boothe). Val Kilmer steals the show as the sickly but deadly gambler and gunslinger Doc Holliday, Wyatt’s unlikely ally.

The film builds tension between the Cowboys and Earps before exploding into the climactic shootout where the lawmen face off against the outlaws on a Tombstone street. Director George P. Cosmatos stages the gunfight as a cacophony of bullets and blood, moving in slow motion at times to focus on each shot fired. Though dramatized, the 30-second shootout captures the real-life events that made Wyatt Earp a legend and embodied the chaos of the untamed Old West.

Beyond its climactic action, Tombstone paints a vivid portrait of the frontier town of Tombstone circa 1880, inhabited by cowboys, miners, gamblers, and local business owners. Though historical accuracy is sometimes sacrificed for drama, the film succeeds in bringing this pivotal chapter in Western history to thrilling cinematic life.

Are These the Best 15 Western Movies Ever?

Westerns have enthralled movie audiences since the earliest days of cinema. From silent films set on the untamed frontier to post-war psychological Westerns that questioned the genres tropes, the best Westerns blend iconic imagery, elemental stories of good vs evil, and a uniquely American mythology. Here is one movie fan’s list of perhaps the top 15 Westerns of all time:

- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966) – Sergio Leone’s epic Civil War Western is a masterclass in visual style and cynicism.

- Unforgiven (1992) – Clint Eastwood’s meditation on violence and the loss of the Old West.

- The Searchers (1956) – John Wayne is unforgettable as Ethan Edwards in this dark Western from John Ford.

- Once Upon a Time in the West (1968) – Director Leone subverts Western myths in this sweeping saga.

- The Wild Bunch (1969) – Sam Peckinpah’s ultraviolent tale of aging outlaws loyal to the end.

- High Noon (1952) – Gary Cooper’s Oscar-winning turn as a sheriff abandoned by his town.