What are the key NCAA women’s lacrosse recruiting rules for 2022-2023. How has the recruiting calendar changed. When can college coaches contact players. What are the differences between Division 1, 2, and 3 recruiting rules.

The Evolution of NCAA Women’s Lacrosse Recruiting Rules

The landscape of women’s lacrosse recruiting has undergone significant changes in recent years. In 2017, the NCAA, in collaboration with USA Lacrosse and the Intercollegiate Women’s Lacrosse Coaches Association (IWLCA), implemented new rules to address the growing trend of early recruiting in the sport. These changes were prompted by a 2017 NCAA study that revealed startling statistics about the recruitment process in women’s lacrosse.

The study found that 81% of women’s lacrosse student-athletes had their first recruiting contact with a college coach before the start of their junior year. This rate of early recruiting was the highest among all NCAA-sanctioned women’s sports. Even more concerning, 44% of the surveyed players reported receiving verbal offers before their junior year.

These findings raised concerns about the impact of early recruiting on student-athletes’ physical and mental development. In response, the new rules were designed to allow more time for athletes to mature before engaging in the recruiting process.

Key Changes in NCAA Women’s Lacrosse Recruiting Rules

The most significant change in the NCAA women’s lacrosse recruiting rules is the restriction on communication between college coaches and student-athletes. Under the new regulations:

- College coaches are prohibited from contacting student-athletes until September 1 of their junior year.

- This includes verbal offers, emails, calls, texts, and recruiting letters.

- These rules apply to all NCAA divisions, making women’s lacrosse subject to some of the strictest recruiting regulations in college sports.

How do these changes affect the recruiting timeline? The new rules have effectively shifted the start of the official recruiting process to later in a student-athlete’s high school career. This change aims to provide athletes with more time to develop their skills and make informed decisions about their college choices.

Division-Specific NCAA Women’s Lacrosse Recruiting Rules

While the general framework of the new recruiting rules applies across all NCAA divisions, there are some division-specific nuances that student-athletes and their families should be aware of:

NCAA Division 1 Women’s Lacrosse Recruiting Rules

Division 1 programs adhere to the strictest recruiting regulations:

- No contact is permitted before September 1 of the athlete’s junior year.

- After this date, coaches can send digital communications, make phone calls, send recruiting materials, and extend verbal offers.

- Official and unofficial visits can be scheduled from September 1 of junior year.

NCAA Division 2 Women’s Lacrosse Recruiting Rules

Division 2 rules are slightly more relaxed:

- Coaches can initiate contact as early as June 15 after the athlete’s sophomore year.

- This earlier contact date allows for a longer recruiting window compared to Division 1.

NCAA Division 3 Women’s Lacrosse Recruiting Rules

Division 3 rules are generally less restrictive:

- There are fewer limitations on when coaches can contact recruits.

- However, many Division 3 programs still adhere to the September 1 junior year contact date to align with Division 1 and 2 practices.

Understanding the NCAA Women’s Lacrosse Recruiting Calendar

The NCAA lacrosse recruiting calendar is divided into several periods, each with its own set of rules and restrictions. Understanding these periods is crucial for both student-athletes and coaches to navigate the recruiting process effectively.

Contact Period

During the contact period, college coaches can communicate with recruits through various means, including in-person meetings, phone calls, emails, and text messages. This is the most open period for recruitment activities.

Evaluation Period

In the evaluation period, coaches can watch athletes compete or practice, but direct contact is limited. This period allows coaches to assess potential recruits’ skills and abilities in their natural playing environment.

Quiet Period

The quiet period restricts in-person contact to the college campus only. Coaches can still communicate with recruits via phone, email, or text, but cannot watch them compete or practice off-campus.

Dead Period

During the dead period, no in-person contact is allowed, either on or off campus. Coaches can still communicate with recruits via phone, email, or text, but cannot conduct any face-to-face meetings or attend competitions.

Preparing for the Women’s Lacrosse Recruiting Process

While official contact with college coaches doesn’t begin until September 1 of junior year, there’s much that prospective student-athletes can do to prepare for the recruiting process:

- Create a strong recruiting profile highlighting academic and athletic achievements.

- Capture and edit a high-quality highlight video showcasing skills and game performance.

- Research potential schools to identify programs that align with academic and athletic goals.

- Attend camps and showcases to gain exposure and improve skills.

- Maintain strong academic performance, as this is a crucial factor in the recruiting process.

How can athletes effectively prepare for the September 1 contact date? By taking these proactive steps, student-athletes can position themselves favorably when coaches are permitted to initiate contact. This preparation can lead to more productive conversations and potentially better recruiting outcomes.

The Role of Club and High School Coaches in the Recruiting Process

Under the new NCAA rules, club and high school coaches play a crucial role in the early stages of the recruiting process. Before September 1 of an athlete’s junior year:

- College coaches can communicate with a recruit’s club or high school coach.

- These conversations are limited to simple Yes or No answers to questions.

- No verbal offers can be made or suggested during these interactions.

This restriction on direct communication highlights the importance of building strong relationships with club and high school coaches. These coaches can serve as valuable intermediaries and advocates in the early stages of the recruiting process.

The Impact of New Rules on Early Recruiting in Women’s Lacrosse

The implementation of new recruiting rules has significantly impacted the landscape of early recruiting in women’s lacrosse. Some key effects include:

- Reduced pressure on young athletes to make early commitments.

- More time for student-athletes to develop physically and mentally before engaging in the recruiting process.

- A more level playing field for late-bloomers who may have been overlooked in the previous system.

- Increased emphasis on academic performance and overall student-athlete development.

How have these changes affected the recruiting strategies of college programs? Many coaches have shifted their focus to thorough evaluation and relationship-building within the permitted timeframes, rather than rushing to secure early commitments.

Navigating the NAIA Women’s Lacrosse Recruiting Landscape

While the NCAA rules govern a large portion of college lacrosse programs, it’s important to note that the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) has its own set of recruiting rules for women’s lacrosse:

- NAIA rules are generally more relaxed compared to NCAA regulations.

- There are fewer restrictions on when coaches can contact recruits.

- NAIA schools often provide opportunities for student-athletes who may not meet NCAA eligibility requirements.

Understanding the differences between NCAA and NAIA recruiting rules can open up additional opportunities for prospective student-athletes. It’s crucial for athletes to consider all available options when navigating the college lacrosse recruiting process.

The Future of Women’s Lacrosse Recruiting

As the landscape of college athletics continues to evolve, it’s likely that recruiting rules and practices will also undergo changes. Some potential areas of future development include:

- Further refinement of recruiting calendars to balance the needs of student-athletes and college programs.

- Increased use of technology in the recruiting process, including virtual visits and digital showcases.

- Greater emphasis on holistic student-athlete development, considering factors beyond athletic performance.

- Potential adjustments to address the impact of Name, Image, and Likeness (NIL) opportunities on the recruiting process.

How might these potential changes shape the future of women’s lacrosse recruiting? As the sport continues to grow in popularity, it’s crucial for all stakeholders – athletes, parents, coaches, and administrators – to stay informed about evolving regulations and best practices in the recruiting process.

In conclusion, the NCAA women’s lacrosse recruiting rules and calendar for 2022-2023 represent a significant shift in how college programs identify and recruit talented student-athletes. By understanding these rules and preparing accordingly, prospective college lacrosse players can navigate the recruiting process more effectively and make informed decisions about their athletic and academic futures.

2022–23 NCAA Women’s Lacrosse Recruiting Rules and Calendar

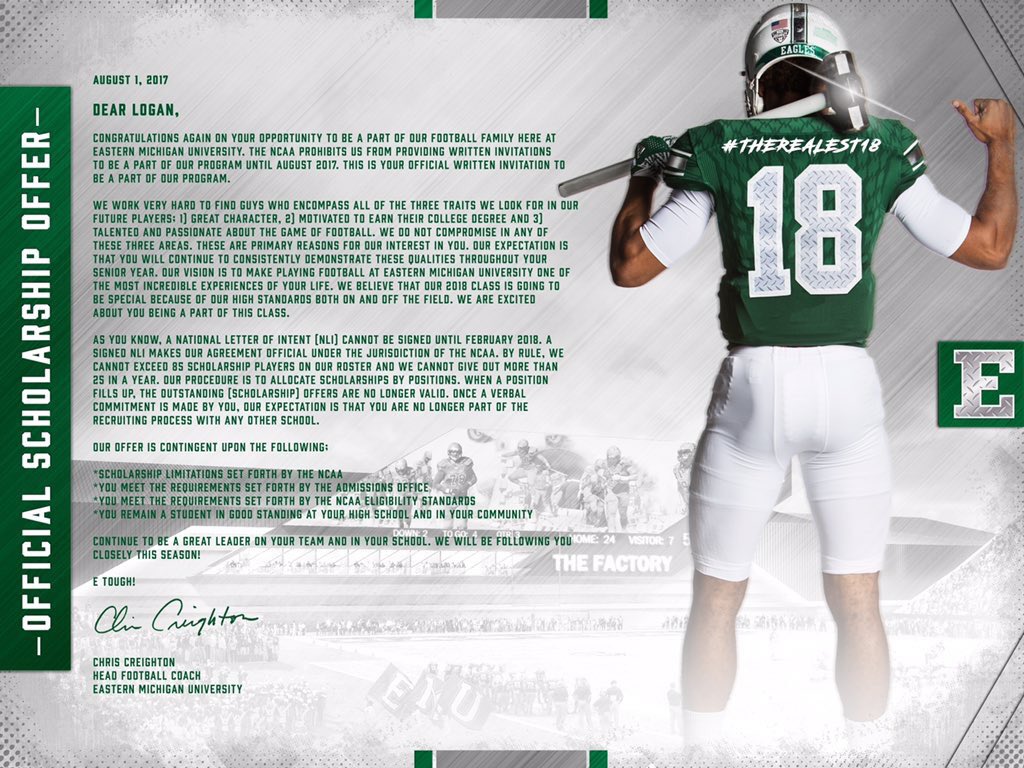

The NCAA, in partnership with USA Lacrosse and the IWLCA and IMLCA, announced a change to the women’s college lacrosse recruiting calendar in 2017. College coaches can contact student-athletes beginning September 1 of their junior year via verbal offers, emails, calls, texts and recruiting letters. Why did college lacrosse recruiting rules change? A 2017 NCAA study revealed that 81 percent of women’s lacrosse student-athletes had their first recruiting contact with a college coach prior to the start of their junior year. Lacrosse had the highest rate of early recruiting when compared to the other ten NCAA sanctioned women’s sports.

Additionally, of the women’s lacrosse players who were surveyed, 44 percent reported that they had received a verbal offer before their junior year. Concerned about the growth of early recruiting, USA Lacrosse and the IWLCA and IMLCA proposed new limitations on college coach and student-athlete communication that would allow more time for student-athletes to develop physically and mentally before the recruiting process starts.

College lacrosse coaches are now held to the strictest recruiting rules of any NCAA sport regarding communication. Contact is no longer permitted between student-athletes and college coaches until September 1 of the athlete’s junior year. While the NCAA has strict recruiting rules for Division 1 sports, some divisions have less restrictive recruiting rules that allow coaches to contact athletes earlier. This section is designed to guide student-athletes and their families through the NCAA lacrosse recruiting rules and calendar, as well as the rules and calendar for the NAIA.

READ MORE: NCAA’s new rules will grant student-athletes the opportunity to earn money from their name, image and likeness (NIL).

Quick Links

How to use the NCAA lacrosse recruiting rules and calendar

When does the women’s lacrosse recruiting process start? When can college coaches talk to players?

Early recruiting in women’s lacrosse

New NCAA women’s lacrosse recruiting rules

NCAA Division 1 women’s lacrosse recruiting rules

NCAA Division 2 women’s lacrosse recruiting rules

NCAA Division 3 women’s lacrosse recruiting rules

NAIA women’s lacrosse recruiting rules

2021-22 division 1 and 2 women’s lacrosse recruiting calendar

What is the quiet period in NCAA lacrosse recruiting?

How to use the NCAA lacrosse recruiting rules and calendar

One way that NCSA aims to reduce the stress around the college recruiting process is by breaking down the NCAA lacrosse recruiting calendar and rules in a way that’s easy to understand. This section focuses on the recruiting rules and regulations that student-athletes and college coaches must follow under both the NCAA and NAIA. This section looks at the recruiting timeline, new lacrosse recruiting rules, early recruitment and the NCAA recruiting calendar.

This section focuses on the recruiting rules and regulations that student-athletes and college coaches must follow under both the NCAA and NAIA. This section looks at the recruiting timeline, new lacrosse recruiting rules, early recruitment and the NCAA recruiting calendar.

When does the women’s lacrosse recruiting process start? When can college coaches contact players?

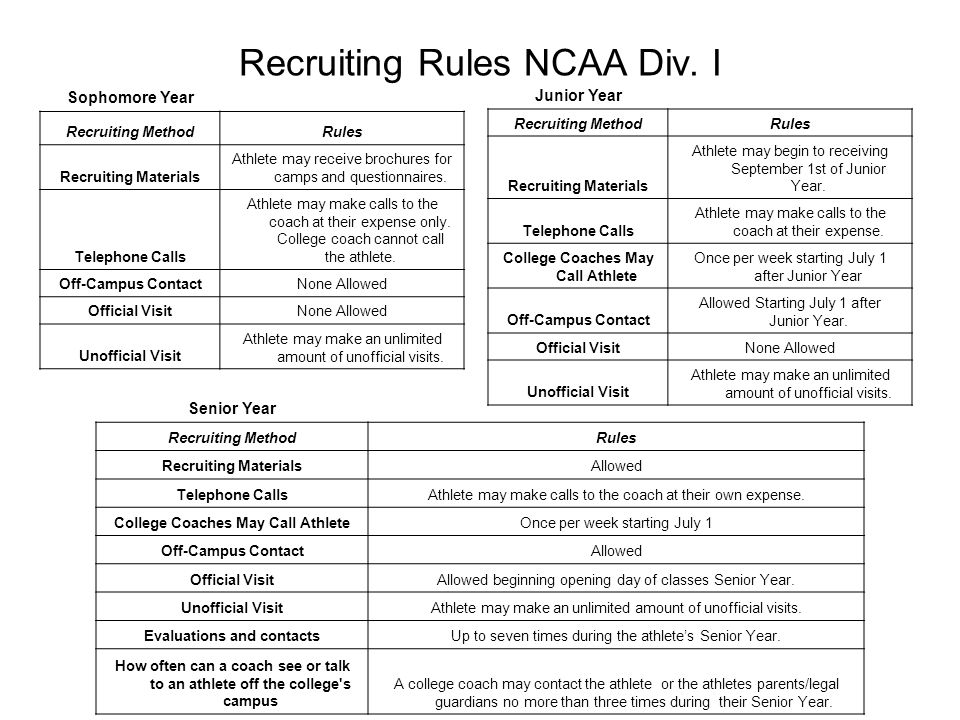

NCAA Division 1 coaches are free to contact recruits after September 1 of the athlete’s junior year. College coaches can send digital communication, make phone calls, send recruiting materials and make verbal offers to recruits. Communication is permitted as early as June 15 after the athlete’s sophomore year for Division II college coaches. Beginning September 1, student-athletes can begin contacting college coaches and scheduling official and unofficial visits.

While official contact with college coaches won’t begin until September 1 of Junior year, there is a lot that prospects should be doing to prepare for that date./cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/60794897/LXM18_PENN_037_.0.jpg) Getting on the radar of college coaches and letting them know you are interested is up to the student-athlete. Student-athletes will need to create a strong recruiting profile, capture and edit a quality highlights video and research potential schools prior to the start of the recruiting process. Student-athletes who prepare for the recruiting process will be better set up for success.

Getting on the radar of college coaches and letting them know you are interested is up to the student-athlete. Student-athletes will need to create a strong recruiting profile, capture and edit a quality highlights video and research potential schools prior to the start of the recruiting process. Student-athletes who prepare for the recruiting process will be better set up for success.

Early recruiting in women’s lacrosse

In 2017, the NCAA established new rules that aim to eliminate the trend of early recruiting. USA Lacrosse and the IWLCA/IMLCA proposed this change to the rules with hopes that it would reduce all forms of early lacrosse recruiting. Before September 1of an athlete’s junior year of high school, college coaches are only permitted to communicate with a recruit’s club or high school coach, though their conversation is restricted to simple Yes or No answers to the questions, and no verbal offers can be made or suggested.

While communication is not permitted before September 1 of the athlete’s junior year, college coaches are still able to prepare for the recruiting process by researching student-athletes. This research includes viewing recruiting profiles and highlight videos, as well as watching the student-athlete’s performance at tournaments. Starting September 1of an athlete’s junior year, college coaches will already have a list of athletes they are interested in recruiting, and they can focus on getting to know those athletes. To catch the attention of college coaches prior to the official start of the recruiting process, it’s critical that student-athletes build a recruiting profile, create highlight video and compete in tournaments.

This research includes viewing recruiting profiles and highlight videos, as well as watching the student-athlete’s performance at tournaments. Starting September 1of an athlete’s junior year, college coaches will already have a list of athletes they are interested in recruiting, and they can focus on getting to know those athletes. To catch the attention of college coaches prior to the official start of the recruiting process, it’s critical that student-athletes build a recruiting profile, create highlight video and compete in tournaments.

New women’s lacrosse recruiting rules

In 2017, the NCAA Division I Student-Athlete Advisory Committee (SAAC) released a study on the recruiting experience for student-athletes. In the study, student-athletes revealed whether college coaches had recruited them earlier than the NCAA allows. Of the 24 NCAA governed sports, early recruiting was found to be at an all-time high in women’s college lacrosse, with 81 percent of student-athletes revealing that their first recruiting contact happened prior to their junior year. To combat the increase of early recruiting in women’s college lacrosse, USA Lacrosse and the IWLCA and IMLCA submitted a proposal to the NCAA requesting new rules on coach and athlete communication, hoping a change to the recruiting timeline would curb early recruiting and reduce some of the pressure on high school underclassmen.

To combat the increase of early recruiting in women’s college lacrosse, USA Lacrosse and the IWLCA and IMLCA submitted a proposal to the NCAA requesting new rules on coach and athlete communication, hoping a change to the recruiting timeline would curb early recruiting and reduce some of the pressure on high school underclassmen.

The NCAA Division 1 Council approved their proposal to prohibit communication between college coaches and student-athletes until after September 1 of the athlete’s junior year. This change to the recruiting timeline allows student-athletes to focus less on college recruiting during their freshman and sophomore year and more on academics, athletic development and enjoying high school.

NCAA Division 1 women’s lacrosse recruiting rules

College coaches and student-athletes are held to the most restrictive rules at the NCAA Division 1 level. Rules vary from sport to sport.

- Any time: Student-athletes can receive non-recruiting materials.

College coaches can send questionnaires, nonathletic institutional publications, camp brochures and official NCAA educational materials.

College coaches can send questionnaires, nonathletic institutional publications, camp brochures and official NCAA educational materials. - September 1 of junior year: Athletes can begin to receive emails, text messages and direct messages from college coaches. College coaches can also begin sending recruiting materials and verbally offer scholarships.

- September 1 of junior year: Student-athletes can begin scheduling unofficial visits and official visits after this date.

- September 1 of junior year: College coaches can conduct off-campus evaluations. Evaluations must take place at the recruit’s school or home during their junior year.

NCAA Division 2 women’s lacrosse recruiting rules

The same NCAA Division 2 recruiting rules apply to all sports. These rules are far more flexible than those in place for NCAA Division 1 schools.

- Non-recruiting materials: College coaches can send non-recruiting materials to student-athletes at any time.

This includes camp NCAA materials, non-athletic recruiting publications, brochures and questionnaires.

This includes camp NCAA materials, non-athletic recruiting publications, brochures and questionnaires. - Printed recruiting materials: Beginning July 15 after an athlete’s sophomore year, college coaches can begin sending printed recruiting materials.

- Telephone calls: Coaches are permitted to start calling athletes, beginning June 15 after an athlete’s sophomore year.

- Off-campus contact: Starting June 15 after an athlete’s sophomore year, off-campus communication is permitted between coaches and athletes and/or their parents.

- Unofficial visits: Student-athletes can make unofficial visits at any time.

- Official visits: Student-athletes may schedule official visits after June 15 of their sophomore year.

NCAA Division 3 women’s lacrosse recruiting rules

NCAA Division 3 schools have the most lenient recruiting rules of all NCAA divisions. These rules apply to all sports.

These rules apply to all sports.

- Recruiting materials: Student-athletes may receive recruiting materials at any time.

- Telephone calls: College coaches may call student-athletes at any time.

- Digital communications: Digital communication between college coaches and student-athletes is permitted at any time.

- Off-campus contact: After an athlete’s sophomore year, athletes and coaches can begin communicating off-campus.

- Official visits: Athletes can schedule official visits starting January 1 of their junior year.

- Unofficial visits: Student-athletes can make as many unofficial visits as they would like.

NAIA women’s lacrosse recruiting rules

NAIA recruiting generally starts later because coaches typically recruit student-athletes who did not receive an offer from an NCAA Division 1 program. Compared to the NCAA, the NAIA has fewer rules around the recruiting process and allows college coaches and athletes to communicate throughout high school without restriction. During the recruiting process, NAIA coaches work to make sure that athletes are a good fit for the program athletically, socially and academically.

During the recruiting process, NAIA coaches work to make sure that athletes are a good fit for the program athletically, socially and academically.

2021-22 Division 1 and Division 2 NCAA women’s lacrosse recruiting calendar

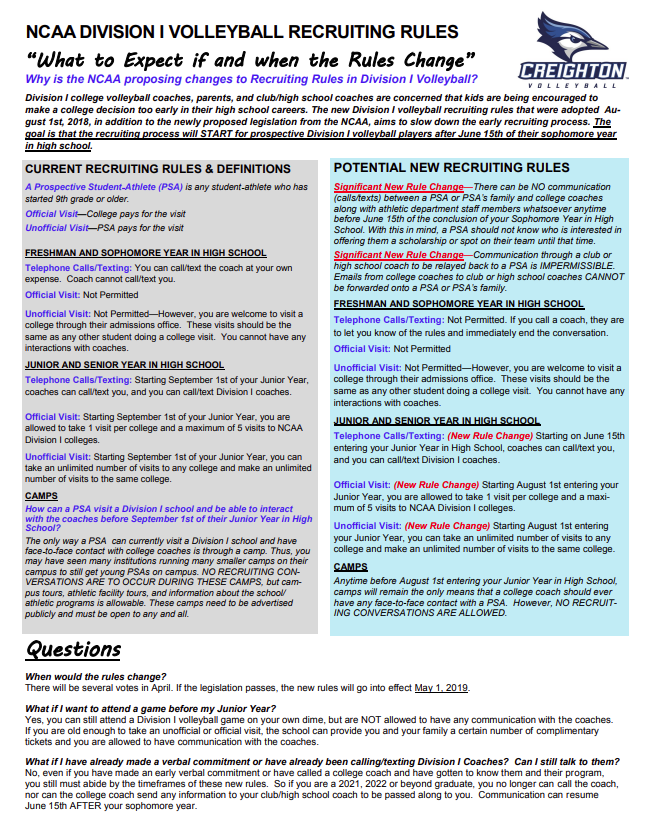

Division 1

Dead periods: During this period, coaches are prohibited from any in-person contact with student-athletes and/or their parents. Athletes and coaches are still permitted to communicate digitally via phone, email, social media, etc.

- Aug. 1-14, 2021

- Nov. 8-11, 2021

- Nov. 24-26, 2021

- Dec. 24-26, 2021

- Dec. 31, 2021-Jan. 2, 2022

- May 27-29, 2022

- Jul. 3-5, 2022

Contact period: College coaches are unable to contact student-athletes, outside of providing camp and clinic information, until September 1 of their junior year. After this date, coaches and athletes are free to communicate through emails, texts, calls and direct messages. This is also when coaches can begin to extend verbal offers to recruits. Dead periods and quiet periods are the only communication restrictions that college coaches must follow after September 1 of the athlete’s junior year.

Dead periods and quiet periods are the only communication restrictions that college coaches must follow after September 1 of the athlete’s junior year.

Division 2

Under the NCAA Divisions 2 lacrosse recruiting calendar, student-athletes can communicate freely with coaches beginning September 1 of their junior year, aside from during one dead period:

- November 8 (7 a.m.) – 10 (7 a.m.), 2021 (during the 48 hours prior to 7 a.m. on the initial date for the signing of the National Letter of Intent).

What is the quiet period in NCAA lacrosse recruiting?

The NCAA created the quiet period to give student-athletes a break from the rigorous recruiting process, while still allowing college coaches and athletes to communicate through NCAA-approved methods (such as, emails, texts, calls and direct messaging). During this time, D1 and D2 college coaches are prohibited from talking to prospective student-athletes in-person, on-campus and cannot visit student-athletes at their high schools, homes or during games.

Division 1

- Aug. 15-31, 2021

Insider tip: Despite the impact that coronavirus had on college sports, as of June 1, 2021, the NCAA resumed its regular recruiting rules and activity! Coaches are actively working to fill their rosters, so student-athletes should be proactive in reaching out to coaches. Read up on how the extra year of eligibility granted to athletes who were most affected by the pandemic in 2020 will impact future recruiting classes.

NCAA RECRUITING INFO / CALENDAR / REQUIREMENTS

DIVISION 1

NCAA INITIAL REQUIREMENTS ELIGIBLITY

***CLICK ABOVE***

DIVISION 2

NCAA INITIAL REQUIREMENTS ELIGIBLITY

***CLICK ABOVE***

Recruiting Calendars

NCAA member

schools have adopted rules to create an equitable recruiting environment that promotes student-athlete well-being. The rules define who may be involved in the recruiting process, when recruiting may

occur and the conditions under which recruiting may be conducted. Recruiting rules seek, as much as possible, to control intrusions into the lives of student-athletes.

Recruiting rules seek, as much as possible, to control intrusions into the lives of student-athletes.

The NCAA

defines recruiting as “any solicitation of prospective student-athletes or their parents by an institutional staff member or by a representative of the institution’s athletics interests for the

purpose of securing a prospective student-athlete’s enrollment and ultimate participation in the institution’s intercollegiate athletics program.”

Frequently

Asked Questions

What is a contact?

A contact

occurs any time a college coach says more than hello during a face-to-face contact with a college-bound student-athlete or his or her parents off the college’s campus.

What is a contact period?

During a

contact period a college coach may have face-to-face contact with college-bound student-athletes or their parents, watch student-athletes compete and visit their high schools, and write or telephone

student-athletes or their parents.

What is an evaluation period?

During an

evaluation period a college coach may watch college-bound student-athletes compete, visit their high schools, and write or telephone student-athletes or their parents. However, a college coach may

not have face-to-face contact with college-bound student-athletes or their parents off the college’s campus during an evaluation period.

What is a quiet period?

During a

quiet period, a college coach may only have face-to-face contact with college-bound student-athletes or their parents on the college’s campus. A coach may not watch student-athletes compete

(unless a competition occurs on the college’s campus) or visit their high schools. Coaches may write or telephone college-bound student-athletes or their parents during this time.

What is a dead period?

During a dead

period a college coach may not have face-to-face contact with college-bound student-athletes or their parents, and may not watch student-athletes compete or visit their high schools. Coaches may

Coaches may

write and telephone student-athletes or their parents during a dead period.

What is the difference between an official visit and an unofficial visit?

Any visit to

a college campus by a college-bound student-athlete or his or her parents paid for by the college is an official visit. Visits paid for by college-bound student-athletes or their parents are

unofficial visits.

During an

official visit the college can pay for transportation to and from the college for the prospect, lodging and three meals per day for both the prospect and the parent or guardian, as well as reasonable

entertainment expenses including three tickets to a home sports event.

The only

expenses a college-bound student-athlete may receive from a college during an unofficial visit are three tickets to a home sports event.

What is a National Letter of Intent?

A National

Letter of Intent is signed by a college-bound student-athlete when the student-athlete agrees to attend a Division I or II college or university for one academic year. Participating institutions

Participating institutions

agree to provide financial aid for one academic year to the student-athlete as long as the student-athlete is admitted to the school and is eligible for financial aid under NCAA rules. Other forms of

financial aid do not guarantee the student-athlete financial aid.

The National

Letter of Intent is voluntary and not required for a student-athlete to receive financial aid or participate in sports.

Signing an

National Letter of Intent ends the recruiting process since participating schools are prohibited from recruiting student-athletes who have already signed letters with other participating

schools.

A

student-athlete who has signed a National Letter of Intent may request a release from his or her contract with the school. If a student-athlete signs a National Letter of Intent with one school but

attends a different school, he or she will lose one full year of eligibility and must complete a full academic year at their new school before being eligible to compete.

What are recruiting calendars?

Recruiting

calendars help promote the well-being prospective student-athletes and coaches and ensure competitive equity by defining certain time periods in which recruiting may or may not occur in a particular

sport.

NBA draft revolution: now future stars do not have to study at least a year at the university. There are 2 alternatives! – Good Sport – Blogs

Scoot Henderson and the Thompson twins are on point.

If, through an effort, you still look beyond the first position in the list of the best basketball prospects of this year, then surprisingly: a) not only Victor Vembanyama participates in the NBA draft and b) rather unusual names “Ignight” and “ Overtime Elite.

Sports.ru 2023 NBA Draft Analysis

A revelation not for everyone, but these are not American colleges from the traditional NCAA-NBA food chain.

For almost 20 years in the NBA it has been forbidden to draft yesterday’s high school students without at least a year at the university, but it seems that the rules have been hacked. Of course, with reservations.

Of course, with reservations.

Prologue. Family circumstances, age, money and money

Until the early 70s, it was possible to enter the NBA draft only four years after graduation. But there was a precedent.

Future Hall of Famer sophomore Spencer Haywood, after winning the Olympics, moved to the Denver Rockets from the ABA (then an NBA competitor). The league was in dire need of young talent and came up with the “Heywood Forced Rule” – an early transition to the pros due to difficult financial and family circumstances. At that time, Spencer’s mother was raising ten children and earning two dollars a day on cotton plantation . A year later, Haywood moved to the NBA and through the court changed the rule of this league already – for an early entry into the draft, the players also had to prove financial difficulties. There were no particular difficulties with using a loophole for first-year students, but schoolchildren were still not drafted (only once, at 1975th, they took two).

Basketball’s baby boom didn’t start until twenty years later, when the Minnesota picked Kevin Garnett in 1995. A chain reaction followed: Kobe Bryant, Jermaine O’Neal, Tracey McGrady, Amare Stoudemire, Dwight Howard and, of course, LeBron James. Three first picks in ten years (Dwight, LeBron, and Kwame Brown, who wasn’t mentioned on purpose).

But in 2005, when negotiating a new Collective Agreement, NBA commissioner David Stern called for a 20-year-old age limit – the league received constant complaints about the pressure on high school students from scouts and general managers who flooded the school halls. It was believed that 9 was mistakenly created for young Americans0021 image of the NBA as an easy way to fame and fortune . Obviously, somewhere in there, the disgruntled ears of the NCAA collegiate league were sticking out, which the main American talents of the generation simply stopped noticing.

The players were against the new restrictions (Jermaine O’Neill even saw a hint of racism), but played a forbidden trick – in exchange for raising the salary cap, the union agreed to a cap of 19 years (in the calendar year of the draft), which effectively meant a year of college education . The rule was called “one-and-done”.

The rule was called “one-and-done”.

The commonplace reason for leaving the NBA early is money. The NCAA does not allow player compensation other than scholarships and benefits such as free meals and training courses. Only in 2021, through the court, students were allowed to earn money by monetizing their image and name – the so-called NIL (Name, Image and Likeness) rules.

Important clarification: the compulsory year after high school could be spent outside of college, but young players need to train and play somewhere to stay on the radar of NBA clubs. Even obvious school talents were forced to play at the university “for food” for some period, until recently there were practically no alternatives to the student league.

Part 1. Rebels from future stars or lessons from the Old World

First, more about “practically”. When there are uncomfortable rules, there will be rebels.

In June 2008, Mr. Basketball USA (wow naming and my personal favorite for a school award) and top high school student in the country, 18-year-old Brandon Jennings announced that he would skip college and play professionally in Europe for a year – the best way to gain experience and earn money to the NBA draft. A month later, he signed a contract with Rome’s Lottomatica for $1.65 million. Plus, he received $ 2 million from Under Armor for advertising the brand in the Euroleague. The NY Times dubbed the event “a lesson from the Old World for the NBA.”

A month later, he signed a contract with Rome’s Lottomatica for $1.65 million. Plus, he received $ 2 million from Under Armor for advertising the brand in the Euroleague. The NY Times dubbed the event “a lesson from the Old World for the NBA.”

After an “impressive” season in Italy, Brandon was selected by Milwaukee in the 2009 NBA Draft with a less than tenth overall pick. There is an additional explanation for this – merit outside the United States was still treated with distrust, especially after the legendary draft of Darko Milicic.

The practice did not become mass, but found its one-time adherents. For example, before the 2015 draft, Emmanuel Mudiay went to China for a year and became richer by $1.2 million. Terrence Ferguson in 2017 was selected in the first round by Oklahoma after a season in Adelaide from the Australian NBL.

Before being selected with the third pick in the 2020 draft, Lamelo Ball traveled to the Lithuanian Prienai at sixteen, becoming the youngest American with a professional contract. True, he played only eight matches there (his father expectedly blamed the coaches) and returned to the USA, where he managed to light up in the unsuccessful phantom competitor of the NCAA – the Youth Basketball Association, created by his enterprising father. The result of ignoring college basketball was Ball’s departure to the Australian Illawarra Hawks from the NBL, where the Next Stars program was launched just from the 2017/18 season – “innovative talent development” from around the world before the NBA draft.

True, he played only eight matches there (his father expectedly blamed the coaches) and returned to the USA, where he managed to light up in the unsuccessful phantom competitor of the NCAA – the Youth Basketball Association, created by his enterprising father. The result of ignoring college basketball was Ball’s departure to the Australian Illawarra Hawks from the NBL, where the Next Stars program was launched just from the 2017/18 season – “innovative talent development” from around the world before the NBA draft.

Although the project did not cause a massive outflow of talent from the United States, it is quite a healthy alternative. It is easier for Americans to adapt there – Australia is closer culturally and linguistically than Europe or Asia. It is also a great opportunity to play not with students, but in a full-fledged adult league with similar regulations.

It was the high-profile departure of LaMelo Ball that caused an obvious fuss in the USA.

Part 2: Ignite or the NBA’s Year of Accelerated Aging

0021 everyone had the opportunity to go somewhere abroad ,” G-League President Sharif Abdur-Rahim expressed concern.

The G-League (formerly the Development League) is the official minor league in the NBA that has been training NBA players, coaches, officials, instructors, and front office staff since 2001. The tournament’s website cheerfully reports that the league offers “high-end professional basketball at an affordable price in a fun, family-friendly atmosphere.” The G-League consists of 30 teams, 28 of which are direct farms of NBA clubs. Many even have the same names – “South Bay Lakers” or “Westchester Knicks”.

Mostly basketball players who have no place in the NBA play there. But this does not mean that they were given up as a bad job. Rather, this is the closest reserve – in the 2022/23 season, a record 47 percent of players on NBA club rosters had experience playing for a farm club in their careers. Among them, for example, status Rudy Gobert, Pascal Siakam and Jordan Poole.

Since 2017, the farms can have two players on a two-way contract (for this, the NBA even expanded the rosters) – such players can be called up by the main team, without the possibility of participating in the playoffs. In particular, last season Scottie Pippen Jr. was on such a contract with the Lakers, Orlando Robinson with the Heat.

In particular, last season Scottie Pippen Jr. was on such a contract with the Lakers, Orlando Robinson with the Heat.

But back to the draft. Young players have been selected from the Development League before. But that was more of a margin of error—only seven cases through 2021, with PJ Hairston’s number 26 being the highest. The fact is that the G-League had the same age restrictions as the NBA, so all young talents under 19 were already in the NCAA or increasingly used alternative options from the previous block. It was decidedly impossible to put up with the second.

So-so attempt. Since 2019 (just after the launch of the Australian startup Next Stars), in the G-League from the age of 18, you can enter into special contracts for 125 thousand dollars with “programming opportunities for development”. The queue did not line up – at the time of the opening of the summer training camps, none of the elite students showed up. And one of the best high school students in the country, RJ Hampton, went to the New Zealand New Zealand Breakers from the NBL for playing practice and a million dollars. The dead end branch was not developed.

The dead end branch was not developed.

Pass attempt. In April 2020, the NBA within the G-League creates an “alternative to college basketball” – a special team “Ignite” based in Henderson, Nevada. Promising players over the age of 18 are offered a salary of up to $500,000, which, with various bonuses, can reach a million. Among other things, players receive full scholarships at the University of Arizona State, which cooperates with the NBA.

The aggressive marketing didn’t end there. On the very first day of existence (still under the working name “Select Team”) “Ignite” introduce the first newcomer – Jaylen Green , the highest school ranked player in the class of 2020. Later, other five-star students were recruited: Isaiah Todd, Deishen Nix and Jonathan Cuminga . A few solid undrafted roleplayers were added to the rotation, as well as the most important ingredients – veterans Jarett Jack, Amir Johnson and Bobby Brown. Former Nuggets head coach Brian Shaw was called in to steer.

Former Nuggets head coach Brian Shaw was called in to steer.

In the very first season, the club reached the playoffs to the quarterfinals (however, due to the pandemic, eleven teams missed the tournament in the “bubble”), which is not particularly important. The main goal of the project was achieved – it turned out to be profitable to highlight talents. In the 2021 draft, Green was taken with the second pick, Cuminga with the seventh pick, and Todd at the start of the second round. Dation Knicks was not drafted, but signed with the Rockets through the summer league that same year.

“If you’re just coming to us for money, it won’t work,” says assistant coach Rod Baker. – People come to Ignite to make their dreams come true… This is the difference between short money and long money.”

The club recruited new young talents without any problems. At the same time, in addition to the next elite high school students Jaden Hardy and Marjon Bowchamp , a local school star symbolically arrived from Australia – Dyson Daniels . All of them were drafted by the NBA clubs a year later.

All of them were drafted by the NBA clubs a year later.

The following are the main advantages of preparing for the draft through Ignight:

• The opportunity to earn quite decent money before the draft , while remaining in a comfortable environment – there is no need to travel to the other side of the world with the appropriate adaptation.

• More than more competitive than college level – playing in the league with “adults”, many with NBA experience. Prospects get used to playing faster, stronger and smarter early in their development.

• G-League, although a lower division, is part of the NBA ecosystem with the appropriate resources, level and reputation.

• Player development. The best coaches and specialists are attracted to the club through the huge resources of the NBA, and purposeful work is carried out to develop each player. The veterans are well chosen.

Sharif Abdur-Rahim is confident the new team will help track elite talent at home as the trend of high school students dropping out of high school and playing abroad continues to grow.

“They used to choose between college or some international team. I think that Ignite meets modern needs – a good option for a young player who is looking for new opportunities, ”said the president of the G-League.

Four Ignite players entered the 2023 draft: defenseman Scoot Henderson, Sidi Sissoko, Mojave King and small forward Lenard Miller . Henderson is the top pick right behind you-know-who.

Part 3 Overtime Elite or the zoomer talent incubator that Drake has already invested in

“If you think about what older audiences like me want, it’s more about nostalgia, like in The Last Dance. But for the younger generation, for our audience, a sense of real time is needed. That’s what we offer ,” said Overtime Elite Youth League President Aaron Ryan.

Overtime sports media company was founded in 2016 by Dan Porter and Zach Weiner. The startup immediately focused on high school basketball, creating short content about high school athletes filmed using iPhone technology.

“In a way, what we’re doing is making a reality show about a new generation of superstars,” Weiner shared. “Most videos are five to ten minutes long, and the production values are often amateur in nature, as if to emphasize authenticity and make the interaction with the viewer more intimate.”

At the initial stage, the startup raised $2.5 million in investments – even ex-NBA commissioner David Stern invested (ironically, he was the one who pushed through the age restrictions for the draft). Within a couple of years, Overtime videos were hitting a billion views every month and expanded into football and video games. It was this project that promoted Zion Williamson and Trae Young long before entering the NBA draft. In total, more than $200 million has been invested in the project.

In 2021, Overtime Elite was launched, a professional basketball league for high school basketball players and international players aged 16 to 19. Basketball players can receive $100,000 or reserve this money as a scholarship for future studies. There are no restrictions regarding advertising contracts.

There are no restrictions regarding advertising contracts.

The league resembles a full-fledged sports academy. In Atlanta, a building of almost 10 thousand square meters was built with playgrounds, a gym, classrooms, a canteen and a hydrotherapy room. Everything is thought out to the smallest detail – even the color design of the arena for the most profitable presentation “for a digital audience.” “Overtime” pays for all expenses for accommodation, meals and development of players, along with academic training.

The project’s $80 million funding includes investments from Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, rapper Drake and about two dozen NBA players including Kevin Durant, Devin Booker, Klay Thompson, Trae Young, Pau Gasol and Carmelo Anthony. The last two are also on the league’s board of directors.

The first major sponsor was the isotonic drink manufacturer Gatorade, which has been the main partner of the NBA G-League since 2017 (the league even rebranded, where G stands for Gatorade).

Former Head of NBA Marketing Aaron Ryan has been named Commissioner of the League, and former Connecticut Coach Kevin Ollie has been appointed Head of Basketball Coaching and Development.

The young franchise’s first recruits were 17-year-old twins Matt and Ryan Bewley, who are among the top students in the country. Two-meter brothers refused to continue their careers in school and college.

Annually (if not daily) the League recruits the best high school students in the country – they got twins Amen and Osara Thompson , Robert Dillingham, Jaden Williams, Bryson Tiller and others. In addition to the American twins, eight scouts track geeks around the world – this is how the MVP of the U-17 World Championship and the U-18 European Championship signed Spaniard Isan Almanza . Now there are more than 30 young talents in the league system.

In the first season, three teams participated in the league, in the second it expanded to six. Naming at the top level – among the banal “Bears”, “Falcons” and “Dreamers” you can meet “City Reapers”, “Cold Hearts” and “Holy Rams”.

Naming at the top level – among the banal “Bears”, “Falcons” and “Dreamers” you can meet “City Reapers”, “Cold Hearts” and “Holy Rams”.

Teams play against each other, as well as exhibition matches with the best high school teams in the country or just the most media ones – for example, with the California Basketball Club of Bronnie and Bryce James or the Christopher Columbus School with the twins Cam and Kayden Boozer. And last summer, the Overtime team went to exhibition matches in Europe, where they played with the Spanish Girona and the Serbian Mega. Broadcasts and related media content reach over 50 million Overtime audiences through apps, social media and YouTube.

So far, there has only been one product of this system in the NBA draft – last year no one selected Dominic Barlow . But later, the small forward was signed by San Antonio, where he played 28 games in the 2022/23 season.

Summarizing the competitive advantages of preparing for the draft through the Overtime Elite program:

• Infrastructure. All experts note the ultra-modern training conditions created in Atlanta.

All experts note the ultra-modern training conditions created in Atlanta.

• Low age limits. There are no other offers on the market for 16-17-year-old players with the opportunity to study, play basketball and earn money.

• Unique academic program with a 4 to 1 student-teacher ratio offering traditional high school courses as well as life skills training such as financial literacy, social media and other media. Mental health and wellness courses included.

• Contract flexibility. A player may forfeit his salary in favor of a guaranteed college scholarship if his basketball career does not work out. At the same time, the player retains the right to monetize his image and name (NIL). Several players have already done this.

“We wanted to find a way to bring together the needs of our business and the needs of the players we covered ,” explained league co-creator Dan Porter.

There are two representatives of Overtime in the top 10 of the upcoming NBA draft – twin forwards Osar and Amen Thompson. Also promising defenders Jezian Gortman and Jaylen Martin showed up for the basketball lottery.

Also promising defenders Jezian Gortman and Jaylen Martin showed up for the basketball lottery.

Passive Antagonist or NCAA Still Relying on Tradition

Super-important clarification: Almost all of the young talents of Ignight and Overtime Elite had several confirmed scholarships from the best colleges in the NCAA system at once, but they voluntarily refused to go down the path of collegiate basketball.

The mission of the NCAA is to train student athletes to excel on the playing field, in the classroom, and throughout life.

Let’s look at the economy of the association in the 2021/22 season. More than a billion dollars were received from two main sources: 940 million for television and marketing rights, plus 198.7 million from ticket sales.

The NCAA includes 90 championships in 24 sports from fencing to bowling, but only five of them are self-supporting: men’s basketball, men’s hockey, men’s lacrosse, wrestling and baseball. Why isn’t American football on the list? The American Football Division I playoffs are run independently – the NCAA receives no revenue. Basketball’s March Madness, on the other hand, feeds almost the entire association – a television contract with CBS Sports alone brings in an average of $ 800 million a year.

Basketball’s March Madness, on the other hand, feeds almost the entire association – a television contract with CBS Sports alone brings in an average of $ 800 million a year.

A quarter of annual income remains with the NCAA for central office funding and “miscellaneous expenses.”

Approximately 75 percent of the NCAA’s progressive income is distributed to colleges and conferences annually, of which more than half goes to sports funding and scholarships for athletes, insurance, various training grants, and courses.

At the same time, only college employees – administrators and coaches – can receive salaries from “sports funding”. And college basketball revenues can fund other sports like figure skating or field hockey. The NCAA estimates that about half a million non-professional athletes receive support in one form or another.

Only two percent of college football and basketball players have ever played a game in the professional NFL or NBA. In addition, many students who don’t get into the professional leagues don’t get a full education: half of all men’s basketball players on full scholarships didn’t graduate from college.

Revolutionary changes in 2021 related to the ability of players to earn money from advertising deals and sponsorships (NIL) really fixed a lot – according to various estimates, this market will generate about $600 million annually. But there is no special merit of the NCAA – this is the execution of the decision of the Supreme Court.

Also, in connection with antitrust cases against the NCAA, athletes are allowed to receive scholarships of up to $6,000 in “tuition fees” and unlimited benefits directly related to education.

Cases are currently in various stages of court to compensate players for income from television rights “that they would have received in a competitive market” and to recognize athletes as employees under the Fair Labor Standards Act. The fact that every cent must be gnawed out in the courts is not the best advertisement for college basketball.

So what are the advantages of the NCAA then? So far, this is more a reflection of the disadvantages of alternative options for young talents:

• Reputation and tradition . The NCAA is still ahead of the alternative leagues in terms of its visible path to glory. March Madness is still breaking TV records. Playing for Duke or North Carolina is a childhood dream for most high school students.

The NCAA is still ahead of the alternative leagues in terms of its visible path to glory. March Madness is still breaking TV records. Playing for Duke or North Carolina is a childhood dream for most high school students.

• Large television contract . NCAA basketball tournaments this year received the highest television ratings in years. The games of competitors from Ignite and Overtime are almost impossible to watch live, the recordings are mainly on YouTube, the quality of the picture and commentary also suffers.

• Fan base . Young projects have yet to find their fans – most of the games are held in empty stands with a corresponding dull entourage. Zoomers don’t go to basketball, they watch it on their gadgets.

• NCAA is still the best junior tournament. G-league – is and will be a minor NBA league, “Overtime” – while closer to the school “Globtrotters”.

More than 85 percent of the players who have entered the upcoming draft are college basketball. The NCAA still has a monopoly on the sports talent market.

The NCAA still has a monopoly on the sports talent market.

Open Finals

The NCAA continues to believe that the ability of players to make money from image will stop the nasty prospect churn. However, in an October 2021 anonymous poll, more than half of college head coaches and assistants expressed varying levels of concern about the possible impact of Ignite and Overtime on the future of college basketball. Last year, five players from these projects were declared in the draft, this year there are already eight, and next year, more than ten may appear in age.

“NIL hasn’t affected our talent pool,” said Ignite head coach Jason Hart. – If a child wants to go to college, he will go there, no matter what. We are not trying to lure children with money. If you come to us and then get a higher draft number, you will end up making more money than you would have received from advertising in your first year.”

Obviously, the basketball talent market is becoming more competitive – time and money dictate their terms. Obsolete rules will always generate some alternative. Stubbornly ignoring this on the part of the NCAA is ossification and self-deception.

Obsolete rules will always generate some alternative. Stubbornly ignoring this on the part of the NCAA is ossification and self-deception.

“Joining Ignite is a dream come true” – At the end of May, the top contender for the first pick of the 2024 draft Matas Buzelis signed a contract with a G-League club.

A month earlier, the school’s 2024 class number one ranked Naasir Cunningham became the first Overtime Elite player to forgo his salary in favor of securing a future college opportunity: “This is the best place for my development. Overtime will help me become the best player possible.” .

Don’t forget about the Australian project Next Star either – a month ago one of the best young Overtime centers Alexander Sarr left for Perth. A little earlier, Illawarra was joined by five-star American schoolboy A.J. Johnson.

Like any lottery, the NBA draft will always have a subjunctive dimension, with Portland going back to 1984 each time to draft Sam Bowie to Michael Jordan. It can be assumed, but it is still impossible to see the future.

It can be assumed, but it is still impossible to see the future.

The upcoming one will probably go down in history “the one when Vembanyama was chosen”, or maybe “when Skoot from Ignite and the Thompson twins from Overtime were chosen”. And one does not exclude the other.

Analysis of the 2023 NBA Draft by Sports.ru

Photo: instagram.com/ote; instagram.com/delawarebluecoats; East News/AP Photo/Jim Mone; Gettyimages.ru/Jim McIsaac, Ethan Miller, Mike Ehrmann, Arturo Holmes, Carmen Mandato

History of Basketball

HISTORY OF BASKETBALL

Teacher of physical culture Petersburg

Shinkarev Mikhail Nikolaevich

Basketball basket “+ ball “ball”) – a sports team ball game in which the ball is thrown with hands into the opponent’s ring.

Basketball is played by two teams, each consisting of five field players (substitutions are not limited). The goal of each team is to throw the ball into the opponent’s net (basket) and prevent the other team from taking possession of the ball and throwing it into their own basket.

The goal of each team is to throw the ball into the opponent’s net (basket) and prevent the other team from taking possession of the ball and throwing it into their own basket.

Basketball, which Americans consider their national sport no less than baseball or American football, was actually invented by a Canadian.

Physical education teacher James Naismith, Canadian of Scottish origin, invented a new sport on December 21, 1891. Basketball is one of the few sports that has an official birth date and can celebrate its birthday. Which we celebrate today, remembering how basketball appeared.

Before we talk about the origins of basketball, we need to know who James Naismith is. James Naismith was not supposed to be a physical education teacher at all. His relatives insisted that he become a priest, and the decision to become a teacher was greeted with horror: in the 1800s, sports in the United States were considered by many to be a tool of the devil, distracting young people from church, work and family. “Years later, I asked my sister if she forgave me for dropping out of my theology studies,” Naismith recalled. “No, Jim,” she replied.

“Years later, I asked my sister if she forgave me for dropping out of my theology studies,” Naismith recalled. “No, Jim,” she replied.

James Naismith did not have a middle name. Many sources gave his full name as “James A. Naismith”, to which Naismith himself joked that the “A” meant “anonymous”.

James Naismith had a difficult childhood. His family emigrated to Canada from Scotland, his father worked for pennies at a sawmill. When he was not even 9 years old, some kind of curse fell on the family: first, James’s grandfather died, the sawmill soon burned down, then his father caught typhus. Little Jim’s uncle took him along with his younger brother and older sister to his place so that the children would not get infected. The elder Naismith soon died of an illness, and three weeks later his wife, who contracted typhus while caring for her husband, also died. So the Naismiths were orphaned, and their uncle and grandmother began to raise them (she will die in two years).

There was little entertainment in the countryside and the children made up their own games. One of these, James’s favorite game, was Duck on the Rock. Each player had a stone, one player (the “defender”) put his on a large stone. Other children stood up 5-6 meters from the stone and tried to knock down the defender’s stone with their stones. If they hit, they stayed in the game, but if they missed, they had to find their stone before they were pinned down by a defender. Naismith liked the game so much because it required accuracy, reaction, and the ability to dodge a defender.

Future professor, doctor and inventor Jimmy Naismith was not a very good student at school. He preferred fresh air to his studies: working on a farm or logging, swimming in a river or fishing, and in winter – sledding or hockey. Three years before graduation, he announced to relatives that he was dropping out of school and would work full-time on a farm. He returned to school only at 19, when his uncle, having seen enough of James’ poor carpentry skills, advised him to use his head instead of his hands.

When Naismith returned to school, he settled in quickly and was promoted to senior class twice during the school year. He was good at mathematics and natural sciences, but there were big problems with languages. However, he overcame them too, and once he, still a schoolboy, was called to replace an ill teacher in a rural school. Naismith’s early students were the best in spelling and the worst in math. So he found out that it is often easier to teach others what he himself once had difficulty learning than what came easily.

Naismith’s McGill University was one of the first in North America to introduce physical education into the curriculum. Especially popular was rugby, which gradually evolved into American football.

Naismith wandered into rugby practice one day. The center of the team broke his nose, and he needed a replacement from the audience. Naismith never played, but volunteered and was such a successful replacement for an injured man that he was offered a spot on the team. James agreed on the condition that he could use the injured player’s kit (he had no money for his own). For the next six years, he played center on the varsity rugby team, never missing a game.

James agreed on the condition that he could use the injured player’s kit (he had no money for his own). For the next six years, he played center on the varsity rugby team, never missing a game.

Naismith’s penultimate and final year was recognized as the best athlete at McGill University. In addition to rugby, he played football and lacrosse, as well as boxing. Naismith’s college motto was “Don’t let anyone work harder than you today.”

After completing his bachelor’s degree, Naismith continued his studies at the Theological School at McGill, aspiring to become a Presbyterian minister, but did not leave the sport, the “tool of the devil” – moreover, he was appointed athletic director of the university after the death of his predecessor.

Naismith soon dropped out without becoming a priest. “I discovered the fact,” he would later write, “that there are other ways to influence the youth than preaching, I felt that I didn’t need to become a priest to change people’s lives for the better. ” One of Naismith’s acquaintances suggested that he become an intern at a college in the American Springfield, Massachusetts, where an educational physical education program was being developed.

” One of Naismith’s acquaintances suggested that he become an intern at a college in the American Springfield, Massachusetts, where an educational physical education program was being developed.

Luther Gulick was in charge of the college’s sports department and is now recognized as the “father of physical education teaching” in the United States.

There were two programs in the college: one for preparing physical education teachers, the other for sports administrators. If the former showed interest in gymnastics, athletics and other indoor sports, because they knew that they would someday have to teach. The future administrators, college students of the Youth Christian Association, forced to do gymnastic exercises, which were considered at that time the only means of introducing young people to sports, were very bored in physical education classes and there was no enthusiasm when they were driven into the gym for an hour.

New sport would not be needed if it were not for winter. At the end of the 19th century, there were not enough games that could be played indoors – gymnastics and aerobics were popular, but not very exciting sports. And in the northern states, like Massachusetts, it was no longer possible to play football, rugby, or baseball in the winter, and hockey had not yet managed to become popular on this side of the border and was too dependent on weather conditions.

At the end of the 19th century, there were not enough games that could be played indoors – gymnastics and aerobics were popular, but not very exciting sports. And in the northern states, like Massachusetts, it was no longer possible to play football, rugby, or baseball in the winter, and hockey had not yet managed to become popular on this side of the border and was too dependent on weather conditions.

The monotony of such occupations had to be put to an end. New games didn’t appeal to them either. At a meeting between faculty, Naismith said that “the problem is not with the people, but with the system we use.” Gulick reacted to these words like a real leader: he appointed Naismith responsible for inventing a new game.

So Naismith, an intern, was tasked with finding a way to get the students involved in something active in the gym. James initially refused this assignment, but soon left his job as a teacher of psychology, theology, wrestling and swimming (such a non-standard set) to invent a new sport for apathetic “clerks”.

Before Naismith, these obnoxious students drove two instructors crazy. James was Luther Gulik’s third and most likely last attempt to introduce winter sports into the educational curriculum.

Another problem was the lack of electrification of society. Under the artificial light in the hall, it was impossible to play sports that would require only accuracy. So at Springfield College, the challenge was to invent a new sport that could be practiced in a dimly lit gym during the winter.

He had 14 days to invent a new game.

The day before the end of the time allotted for inventing a new game, Naismith was in a panic – he never came up with anything. Then he tried to approach the problem from a different angle. Why did attempts to modify the old fail? Because people liked those games as they are, without innovation. How is an abstract sports game built in general? Usually there is a ball in it. So the future game has a central element around which it is built.

So the future game has a central element around which it is built.

But balls are also different. If the ball is small, you need a lot of equipment for it – clubs, bats, goals, pads, masks, and so on. And the more inventory, the more complicated the rules, but you need a simple game. Another small ball is easier to hide somewhere in a playful way. It is more convenient to work with a big ball.

The second task was to define the philosophy of the sport. Rugby couldn’t be played in small halls because that would lead to a lot of injuries due to collisions. Collisions occur to stop the person running with the ball. “I sat at the table with these thoughts and said out loud: “If he does not run with the ball, he will not need to be captured. If he is not captured, there will be no roughness in the game.” I still remember how I snapped my fingers and shouted: “Found it!” Naismith later wrote. Thus was formed the basic principle of the new game – you can not run with the ball. Hardly a detailed description, but it was only the first stroke of a sketch of the future sport.

Hardly a detailed description, but it was only the first stroke of a sketch of the future sport.

The third task is to justify the purpose of the game. At first, Naismith wanted the ball to be thrown into opposing goals, like in lacrosse – a net of 2 by 2.5 meters. But if the ball is thrown too hard, they will hit another player and injure him, and this again is not suitable. And then Naismith remembered his childhood and playing Duck on the Stone. It was not about strength, but about accuracy, which was precisely the special trait that Naismith was looking for in his new game: “I thought that if the target to be hit was horizontal instead of vertical, then players would have to throw the ball in an arc. Strength, the essence of rudeness, will be useless.

Naismith also decided that the goal should be suspended over the heads of the players so that the defenders could not crowd around it and block the path of the ball. We are already groping for something similar to the basketball we know, aren’t we?

Many, not knowing that Naismith did not have a historical education, and at the end of the 19th century, the history and customs of some kind of Indians were not interested in the bulk of white people. Therefore, the statement that the progenitor of modern basketball is the ritual game of the ancient Maya Indians pok-ta-pok is frankly “far-fetched”.

Therefore, the statement that the progenitor of modern basketball is the ritual game of the ancient Maya Indians pok-ta-pok is frankly “far-fetched”.

On the morning of December 21, 1891, an enthusiastic James Naismith arrived at work. From this moment begins a continuous series of accidents and improvisations. Naismith had two balls to choose from – one for rugby, the other for football. The rugby ball is stretched out so that it can be carried in the hands, James concluded, and in the new game, to avoid roughness, this is not necessary. Therefore, a round ball was chosen.

The first version of our usual basketball basket was a pair of half-meter by half-meter boxes. True, they existed only in the imagination of Naismith. Naismith gave the college janitor the task of bringing them to the gymnasium, but he did not find anything suitable and offered two baskets of peaches. Thus, the “basket ball” was born. Remember this name forever – Pop Stebbins – that was the name of the janitor who found the peach baskets in his pantry. It was to him that Naismith entrusted “the honorable right to be on duty with the ladder during the match, to retrieve the balls thrown into the baskets.

It was to him that Naismith entrusted “the honorable right to be on duty with the ladder during the match, to retrieve the balls thrown into the baskets.

Baskets were attached to the balcony railing at a height of 10 feet (304.8 cm). “If the railing was 11 feet high, that’s where I would have secured it,” Naismith said. But the dynamics of basketball would change if it became more difficult to score from above or shoot from afar.

Naismith wrote the rules for the new game in less than an hour, then gave them to a college stenographer, Miss Lyons, to type them out.

There were only 13 rules. They were attached with a pair of thumbtacks on the bulletin board in the gym – and so they became official.

The first game went 9 on 9, simply because there were 18 students in the group. The walls of the hall served as the boundaries of the site, the lighting was weak, and the players did not have any special equipment. Naismith placed the players on the court like in lacrosse – three for defense, three for center, three for offense, called two players, tossed the ball – and a new game was born.

Naismith placed the players on the court like in lacrosse – three for defense, three for center, three for offense, called two players, tossed the ball – and a new game was born.

Naismith later recalled: “After a few minutes, it became clear to the experimenter that the game was a success. The players seemed to enjoy the vicissitudes of the game with all their hearts, especially trying to avoid a collision with an opponent. The game captivated the students so much that they wanted to continue it even after the lesson was over.

The hardest thing for early basketball players to adjust to was the sudden stop after receiving the ball. The natural instinct is to keep moving with the ball. But this was a violation, and according to the rules, the player was removed from the court after a foul until the next hit. “It happened that there were half a team in the penalty area,” Naismith recalled.

Rudeness was also present. The list of injuries in the first game, according to Naismith: several black eyes, one dislocated shoulder, one loss of consciousness. Not bad for half an hour of play.

The list of injuries in the first game, according to Naismith: several black eyes, one dislocated shoulder, one loss of consciousness. Not bad for half an hour of play.

Only one goal was scored in the game. The author of the historic hit was William Chase, who threw the ball into the basket from 8 meters. Among the 18 participants in the first basketball game was even a Japanese – Genzabaro Ishikawa, who would later introduce his homeland to a wonderful new game. Other participants in the first match brought basketball to France, India, Great Britain and Persia.

Soon rumors about a new, as yet unnamed game spread throughout the school, and spectators began to come to the matches. Two weeks later, 100 people turned up at one of the games – including a group of students from Buckingham Women’s College who were returning from lunch and accidentally walked past the hall and heard a noise. The Buckingham teachers approached Naismith after the game and asked if they could also play basketball. Naismith didn’t mind, and the first women’s basketball team was born. They were opposed by a team of stenographers from Springfield College.

Naismith didn’t mind, and the first women’s basketball team was born. They were opposed by a team of stenographers from Springfield College.

In January 1892, the rules of basketball were published in the Springfield College newspaper, The Triangle. She, of course, had nothing to do with the “triangular attack”: the triangle was the emblem of the YMCA, which was once invented by Naismith’s college boss Luther Gulick.

The Triangle editors received so many requests for a copy of the rules that they published a separate booklet that also described the necessary equipment for the game.

Already in April 1892, the game was written about in the New York Times under the heading “A new ball game, a replacement for football without rudeness.”

The first basketball was made by the bicycle factory Overman Wheel Co. from Massachusetts. It was lighter and larger than the soccer ball that had been played before.

The first balls were brown, and only many years later they began to make them orange – so that the audience could see the ball better from the stands. In the late 1890s, Naismith asked A.G. Spaulding to develop an improved version of the basketball. And after more than 100 years, Spalding balls are official in the NBA, but only earlier they were not very even, not very round and with lacing, which made dribbling difficult.

In the US, basketball was distributed to educational institutions as part of physical education lessons. Even before the beginning of the 20th century, basketball appeared in Canada, where college and university students also liked it. James Naismith promoted basketball in the United States, and the MXA college, where the first game took place, regulated the rules of the game for about the first ten years of basketball’s existence.

Ten years later, Spaulding will release the first special basketball shoe.

With the spread of the game, the first inconvenience appeared: climbing on the ladder to get the ball out of the basket after each hit was annoying. At Springfield College, a special person sat on the balcony to take the ball out of the basket. Then someone suggested cutting the bottom of the baskets – alas, history has not preserved the name of the author and the place of this important invention. But even the bottom was cut out not so that the ball would fall through, but so that it could be pushed out of the basket from below with a stick. “Since the stick was often not available,” Naismith recalled, “we had to use other objects. Fortunately, the inexperience of the players led to the fact that the ball was thrown into the basket very rarely.

At Springfield College, a special person sat on the balcony to take the ball out of the basket. Then someone suggested cutting the bottom of the baskets – alas, history has not preserved the name of the author and the place of this important invention. But even the bottom was cut out not so that the ball would fall through, but so that it could be pushed out of the basket from below with a stick. “Since the stick was often not available,” Naismith recalled, “we had to use other objects. Fortunately, the inexperience of the players led to the fact that the ball was thrown into the basket very rarely.

In 1898 the baskets were changed to rings with a net attached. By 1912, rings with a hole in the bottom of the mesh were already common.

Since most of the halls had balconies, spectators sat behind the rings, and some unscrupulous fans could interfere with the ball entering the basket. And the organizers of the matches came up with another important element of basketball – the shield. True, no one imagined that the shield would make it easier for the ball to hit the basket and increase the effectiveness, and, consequently, the entertainment of the sport.

True, no one imagined that the shield would make it easier for the ball to hit the basket and increase the effectiveness, and, consequently, the entertainment of the sport.

In 1895, the first university match was played between Minnesota Public School of Agronomy (now the University of Minnesota at St. Paul) and Hamline College (now Hamline University). Although the first student team appeared in Vanderbilt in 1893, it did not play with other colleges.

Basketball was spreading at such an alarming rate that the YMCA banned it in some places in the US – basketball games were crowding other sports out of gyms. Then basketball players had to move to ballrooms, arsenals, hangars and other large indoor facilities.

It’s funny, but in Springfield itself basketball did not take root on the first try – in 1899 the basketball team was disbanded and returned only in 1907.

One of Naismith’s students in Springfield was William Morgan. In 1895, he decided to invent his own game – so in Holyoke, 10 kilometers from Springfield, “mintonette” was born. We know him now by the name “volleyball”.

In 1895, he decided to invent his own game – so in Holyoke, 10 kilometers from Springfield, “mintonette” was born. We know him now by the name “volleyball”.

Already in 1896, only five years after the invention of basketball, the first professional basketball game took place. It was held in the ballroom, and so that the ball would not fly away to the audience, the parquet was fenced with wire mesh. This is how the first term for the name of basketball and basketball players appeared – “Cage Game”, “cagers”, “cell players”. It was easy to get hurt on the wire, so it was usually replaced by a net of ropes – and so the professionals played up to 1940s. In college basketball, the “cage” was banned almost immediately.

In 1898 the first professional league was born. Six teams made up the National Basketball League – this name (NBL) in forty years will be inherited by the parent league of the NBA. Players earned about $10 per match.

Naismith ignored his invention for a very long time. For him, it was just a small game that was inferior to gymnastics and wrestling in its usefulness.

For him, it was just a small game that was inferior to gymnastics and wrestling in its usefulness.