How do militaries observe regions to locate enemies. What warning systems are employed in military science. How have observation techniques evolved throughout history. What modern technologies are used for enemy detection.

The Evolution of Military Observation and Warning Systems

Military observation to locate enemy forces has been a crucial aspect of warfare throughout history. As tactics have continuously emphasized the element of surprise, defenders have sought to develop increasingly sophisticated warning systems to counter these strategies. Let’s explore how these systems have evolved over time and examine the various types used in modern military operations.

Early Warning Systems in Ancient Warfare

In ancient times, military forces relied primarily on visual observation and basic defensive measures:

- Flank and rear guards for marching columns

- Scouts and patrols to locate enemy positions

- Sentries guarding encampments

- Use of animals like dogs and horses for detection

- Watchtowers and high ground for improved visibility

One fascinating historical example comes from ancient Rome. According to the historian Livy, geese were instrumental in detecting a night attack by the Gauls on Rome in the 4th century BC. This demonstrates how even simple warning systems could play a crucial role in military defense.

Technological Advancements in the 18th and 19th Centuries

The 18th and 19th centuries saw significant advancements in military observation technology:

- Observation balloons: First used by the French in the late 18th century

- Aerial photography: Pioneered by the French and used in the 1859 War of Italian Independence

- Telegraph and telephone: Improved long-distance communication

- Binoculars and telescopes: Enhanced visual observation capabilities

The American Civil War demonstrated the defensive potential of observation balloons. In May 1863, a balloon used by the Army of the Potomac detected Lee’s army movement, providing crucial intelligence at the outset of the Gettysburg campaign.

Modern Military Warning System Classifications

In contemporary military science, warning systems are typically classified into three main categories based on the timeframe and scope of the information they provide:

1. Long-term (Political) Warning Systems

These systems focus on identifying potential threats well in advance by analyzing various indicators:

- Diplomatic signals

- Political developments

- Technological advancements

- Economic trends

How do nations respond to long-term warnings? Defenders may react by strengthening their military capabilities, engaging in diplomatic negotiations, or taking other preemptive actions to mitigate potential threats.

2. Medium-term (Strategic) Warning Systems

Strategic warning systems typically provide information within a timeframe of days to weeks. They aim to alert defenders that hostilities may be imminent, allowing for more immediate preparations and strategic planning.

3. Short-term (Tactical) Warning Systems

Tactical warning systems operate on the shortest timescale, often providing alerts just hours or minutes before an attack. These systems are critical for immediate defensive actions and rapid response to enemy initiatives.

The Distinction Between Warning and Detection in Military Operations

It’s crucial to understand that warning and detection are separate but interconnected functions in military observation:

Detection Devices (Sensors): These systems perceive various aspects of potential enemy activity, including:

- Presence or proximity of enemy forces

- Enemy location and size

- Ongoing activities

- Weapon capabilities

- Changes in political, economic, technical, or military posture

Warning Systems: These encompass a broader process that includes:

- Detection devices

- Communications networks

- Information analysis

- Decision-making procedures

- Implementation of appropriate actions

Why is this distinction important? Understanding the difference between detection and warning helps military planners develop more comprehensive and effective defensive strategies that go beyond simply identifying threats to include rapid response and mitigation measures.

Modern Technologies in Military Observation and Detection

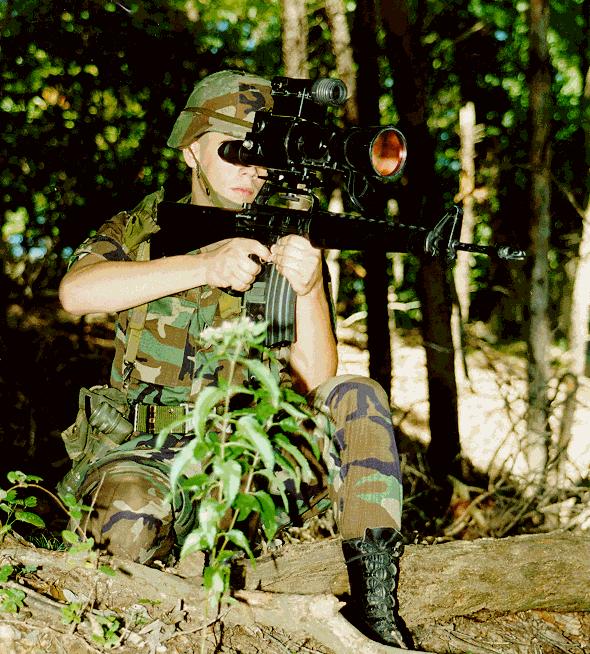

Today’s military forces employ a wide array of advanced technologies for observation and detection:

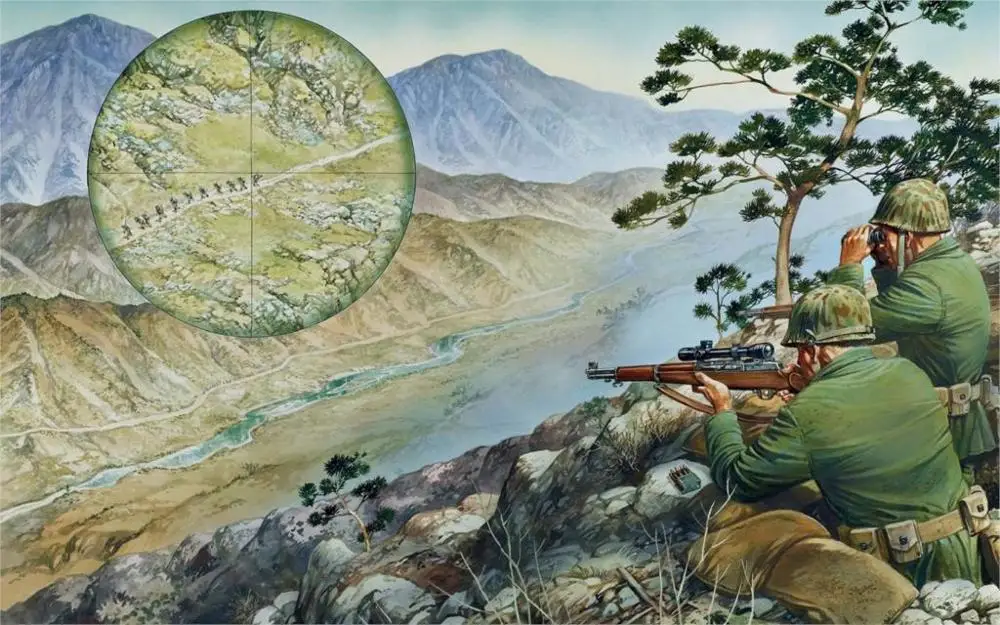

- Visual observation equipment (e.g., high-powered optics)

- Cameras and imaging systems

- Heat-sensing devices

- Low-light-level detection systems

- Radar installations

- Acoustic sensors

- Seismic detection equipment

- Chemical sensors

- Nuclear detection devices

How do militaries manage the vast amounts of data generated by these systems? Modern warning systems rely heavily on computer technology to process, condense, and summarize the enormous volume of information produced by various sensors. This data integration is crucial for providing decision-makers with actionable intelligence.

The Challenge of Information Overload

While advanced sensors provide unprecedented levels of information, they also present new challenges. The sheer volume of data can be overwhelming, making it difficult to identify critical threats amidst the noise. To address this, militaries invest heavily in:

- Advanced data analytics software

- Artificial intelligence and machine learning systems

- Secure and robust communication networks

- Training for intelligence analysts and decision-makers

The Role of Airborne Warning and Control Systems (AWACS)

One of the most sophisticated modern warning systems is the Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS). These aircraft, such as the U.S. Air Force Boeing E-3 Sentry, serve as mobile, long-range radar and command and control centers.

Key Capabilities of AWACS Aircraft:

- All-weather surveillance of large airspace areas

- Detection and tracking of aircraft and vehicles at extended ranges

- Integration of sensor data from multiple sources

- Real-time information dissemination to command centers and other assets

- Airborne command post functionality for battlefield management

How do AWACS aircraft enhance military situational awareness? By combining powerful radar systems with advanced communications and data processing capabilities, AWACS platforms provide a comprehensive, real-time picture of the battlefield. This allows for rapid decision-making and coordinated responses to emerging threats.

The Importance of Communication in Warning Systems

While sophisticated sensors and detection devices are crucial components of modern warning systems, the communication infrastructure that supports them is equally vital. Effective warning relies on the rapid and secure transmission of information from sensors to decision-makers and then to defensive assets.

Key Elements of Military Communication Systems:

- Secure, encrypted communication channels

- Redundant networks to ensure reliability

- High-bandwidth data links for real-time information sharing

- Interoperable systems allowing communication between different branches and allies

- Robust, hardened infrastructure to withstand attacks or interference

Why is communication often considered the weakest link in warning systems? Despite technological advancements, the challenge of rapidly transmitting, interpreting, and acting on information remains significant. Factors such as information overload, potential for miscommunication, and vulnerabilities to electronic warfare all contribute to this challenge.

Historical Successes and Failures in Military Warning

Throughout history, there have been numerous instances of both successful military surprises and effective warnings. Examining these cases provides valuable insights into the importance of robust observation and warning systems.

Notable Failures in Military Warning:

- Pearl Harbor attack (1941): Despite some indications of impending Japanese action, the U.S. failed to anticipate the specific threat to Pearl Harbor.

- Operation Barbarossa (1941): The Soviet Union was caught unprepared by the German invasion, despite multiple warning signs.

- Yom Kippur War (1973): Israel was surprised by the coordinated Egyptian-Syrian attack, highlighting the dangers of overconfidence in existing defenses.

Successful Applications of Warning Systems:

- Battle of Midway (1942): U.S. code-breaking efforts provided crucial warning of Japanese plans, allowing for a decisive American victory.

- Cuban Missile Crisis (1962): U.S. aerial reconnaissance detected Soviet missile installations in Cuba, enabling diplomatic resolution of the crisis.

- Gulf War (1991): Coalition forces effectively used satellite imagery and other intelligence to track Iraqi military movements and preparations.

What lessons can be drawn from these historical examples? They underscore the critical importance of not only having advanced warning systems but also properly interpreting and acting upon the information they provide. Overconfidence, political considerations, and cognitive biases can all lead to failures in recognizing and responding to warnings.

The Future of Military Observation and Warning Systems

As technology continues to advance at a rapid pace, the future of military observation and warning systems is likely to see significant developments:

Emerging Technologies in Military Observation:

- Quantum sensors for enhanced detection capabilities

- Advanced AI and machine learning for faster data analysis

- Hyperspectral imaging for improved target identification

- Autonomous drone swarms for wide-area surveillance

- Space-based sensors for global monitoring

How will these technologies shape future military operations? They promise to provide even more comprehensive situational awareness, faster reaction times, and the ability to detect increasingly sophisticated threats. However, they also raise new challenges in terms of data management, system integration, and potential vulnerabilities to cyber attacks or electronic warfare.

Ethical and Legal Considerations

The advancement of military observation technologies also brings forth important ethical and legal questions:

- Privacy concerns related to widespread surveillance capabilities

- International laws governing the use of space-based sensors

- Ethical implications of AI-driven decision-making in military contexts

- Potential for technology proliferation and its impact on global stability

How will nations balance the need for effective defense with respect for individual rights and international norms? This ongoing debate will likely shape the development and deployment of future military observation and warning systems.

In conclusion, the field of military observation and warning systems continues to evolve, driven by technological advancements and the ever-changing nature of global threats. While modern militaries possess unprecedented capabilities for detecting and responding to potential enemies, the fundamental challenges of interpreting information, making timely decisions, and effectively communicating warnings remain as relevant today as they were in ancient times. As we look to the future, the integration of cutting-edge technologies with human expertise and judgment will be crucial in developing warning systems that can effectively safeguard nations in an increasingly complex global security environment.

Warning system | military technology

Warning system, in military science, any method used to detect the situation or intention of an enemy so that warning can be given.

Warning system

U.S. Air Force Boeing E-3 Sentry, an airborne warning and control system (AWACS) aircraft.

U.S. Air Force

Because military tactics from time immemorial have stressed the value of surprise—through timing, location of attack, route, and weight and character of arms—defenders have sought to construct warning systems to cope with all these tactics. Many types of warning systems exist. Long-term, or political, warning systems employ diplomatic, political, technological, and economic indicators to forecast hostilities. The defender may react by strengthening defenses, by negotiating treaties or concessions, or by taking other action. Political warning, equivocal and incapable of disclosing fully an attacker’s intention, often results in an unevaluated and neglected situation.

Medium-term, or strategic, warning, usually involving a time span of a few days or weeks, is a notification or judgment that hostilities may be imminent. Short-term, or tactical, warning, often hours or minutes in advance, is a notification that the enemy has initiated hostilities.

Warning and detecting are separate functions. The sensors or detection devices perceive either the attack, the possibilities of an attack, the nearness of the enemy, his location, his size, his activities, his weapon capability, or some changes in his political, economic, technical, or military posture.

Get a Britannica Premium subscription and gain access to exclusive content.

Subscribe Now

Warning systems include detection devices but also imply the judgments, decisions, and actions that follow receipt of the sensor’s information. Warning encompasses communications, analysis of information, decisions, and appropriate actions. Visual observation still remains important, supplemented by telescopes, cameras, heat-sensing devices, low-light-level devices, radar, acoustic, seismic, chemical, and nuclear detection devices. The product, or output, of these sensors is complicated and voluminous and requires computers to condense and summarize the data for the decision maker. Often, the most expensive portion and weakest link of the warning system is not the sensor but the communication and evaluation systems. Technology of all types is required in modern warning systems.

The product, or output, of these sensors is complicated and voluminous and requires computers to condense and summarize the data for the decision maker. Often, the most expensive portion and weakest link of the warning system is not the sensor but the communication and evaluation systems. Technology of all types is required in modern warning systems.

History

History abounds with examples of successful military surprises; examples of effective warning are difficult to find. Military training emphasized the value of surprise, stratagem, and deception, but the value of warning was long neglected. Flank and rear guards, to protect marching columns, patrols and scouts to locate the enemy, and sentries to guard camps, were of course used in war from earliest times. Animals were sometimes employed to detect the approach of an enemy; dogs and horses were especially favoured, though, according to the ancient historian Livy, the Romans used geese to detect the night attack of the Gauls on Rome in the 4th century bc. High ground, favourable for observation, was often supplemented by watchtowers, such as those placed along the Great Wall of China and on Hadrian’s Wall in Britain.

High ground, favourable for observation, was often supplemented by watchtowers, such as those placed along the Great Wall of China and on Hadrian’s Wall in Britain.

The observation balloon was an important technological advance. First used in warfare by the French in the late 18th century, primarily for offensive reconnaissance on the battlefield, its defensive possibilities were demonstrated in the American Civil War; in May 1863 a balloon of the army of the Potomac detected Lee’s army moving from its camp across the Rappahannock to commence the Gettysburg campaign. Aerial photography had already been pioneered by the French and used in the War of Italian Independence (1859).

A balloon observer in the Spanish-American War of 1898 is credited with discovering an alternate route up San Juan Hill during the battle there. A few other successes are ascribed to such observation before the balloon was supplemented by the far more valuable airplane in World War I. Nevertheless, the balloon never fulfilled its potential as a warning device.

In sea warfare, warning and detection were equally neglected. As far back as the Minoan civilization of Crete, patrol ships were used, but mainly for offensive purposes. In later centuries, raised quarterdecks and lookout posts atop sailing masts were provided, but the beginnings of serious maritime detection technology did not come until the advent of the submarine.

Binoculars, telescopes, the telegraph, and telephone were well established military equipment by 1914; the airplane, first used by the Italians in the Italo-Turkish War of 1911, showed its potential as an observation device at the Battle of the Marne. Radio communications provided the means to make air observations immediately available. Aerial combat became inevitable as each side tried to deny the other its aerial reconnaissance.

Searchlights, first used in the Russo-Japanese War (1904), saw large-scale use in World War I to detect dirigibles and aircraft on night bombardment missions. Flares were used to illuminate the battlefield between trenches to detect raiding parties. Listening devices, using directional horns to detect and locate enemy aircraft, were also used with limited success.

Listening devices, using directional horns to detect and locate enemy aircraft, were also used with limited success.

Despite the novelties of World War I, World War II produced far more technological innovation. Radar made obsolete the slow and inaccurate older listening devices. Radio communications made great strides, particularly in the very high frequency range. The combination of radar and interference-free very high frequency communications was pivotal in permitting the RAF to resist Hitler’s aerial attack and win the Battle of Britain.

Notwithstanding radar sophistication, ground spotters played an important role in filling the gaps between radar coverage. Their messages, forwarded to a plotting centre, were assembled to trace the progress of intruders (tracking).

The advent of nuclear weapons (1945), especially when coupled later with the speed and range of intercontinental missiles, gave new dimensions to the value of surprise for the attacker. Long-term warning was suddenly of paramount importance. Not only did all forms of unequivocal warning become indispensable but the warning had to be made credible to an aggressor; that is, an assurance had to be given that the retaliatory weapons would not all be destroyed by a first strike. Bomber aircraft were kept in the air to avoid destruction on the ground and attempts were made to provide a degree of protection for the civilian population through shelters.

Not only did all forms of unequivocal warning become indispensable but the warning had to be made credible to an aggressor; that is, an assurance had to be given that the retaliatory weapons would not all be destroyed by a first strike. Bomber aircraft were kept in the air to avoid destruction on the ground and attempts were made to provide a degree of protection for the civilian population through shelters.

Practically all aspects of science and technology have been introduced into today’s warfare and warning systems: airplanes, helicopters, submarines, earth satellites, television, lasers, and magnetic, acoustic, seismic, infrared, nuclear, and chemical detectors.

The Museum of the Staffordshire Yeomanry

Battalion: a large body of troops ready for battle, especially an infantry unit forming part of a brigade.

Brigade: a subdivision of an army, typically consisting of a small number of infantry battalions and/or other units and forming part of a division.

Cadre: a small group of people specially trained for a particular purpose or profession.

Cap badge: A badge worn on uniform headgear to distinguish the wearer’s regiment. A modern form of heraldry, its design is highly symbolic. The original Staffordshire Yeomanry cap badge incorporated the Stafford Knot, which some say was devised as a means of multiple execution while others insist it represents the joining of three geographical areas!

Cavalry: (in the past) soldiers who fought on horseback.

Division: a group of army brigades or regiments.

Infantry: soldiers marching or fighting on foot; foot soldiers collectively.

Orbat: short for order of battle, the strategic arrangement of armed forces participating in a military operation.

Rank: a relative status or position, showing the level of authority of the person. Rank badges in the British Army are a simple method of identifying someone’s status.

Recce: Short for ‘reconnaissance’, a military observation of a region to locate an enemy or ascertain strategic features.

Regiment: a permanent unit of an army typically commanded by a Lieutenant Colonel and divided into several companies, squadrons.

Sabre troop: a fighting unit of sub-battalion size. The term originated in the British Army, and is derived from the sabre traditionally used by cavalry.

Squadron: a principal division of an armoured or cavalry regiment, consisting of two or more troops.

Troop: a military sub-unit, originally a small formation of cavalry, subordinate to a squadron.

Yeomanry: a volunteer cavalry force.

Electronic Records Relating to the Vietnam War

Reference Report

Introduction

This reference report provides an overview of the electronic data records in the custody of the National Archives that contain data related to military objectives and activities during the Vietnam War.

The National Archives holds a large body of electronic records that reflects the prolific use of computers by the military establishment in carrying out operations during the Vietnam War. Under the auspices of Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, the military implemented an extensive data collection effort intended to improve the conduct of the conflict. The raw data documented details of casualties, military operations, military logistics, pacification programs, and other aspects of the war. With the data in electronic form, analysts performed statistical and quantitative analysis to assess and influence the direction of the conflict. After the conflict ended in the 1970’s, various Department of Defense organizations, including the Office of the Secretary of Defense, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Joint Commands, transferred the raw data files to the National Archives. Some of these records include documentary material that has not been transferred to the National Archives in any other format.

This reference report is organized by nine broad categories of Vietnam War data as listed above in the table of contents. For each category, the relevant electronic records series are listed along with information about the number of files, available output formats (see Output Formats for details), and technical documentation. Many of the series listed also have supplemental documentation. Since some series contain data applicable to more than one category, researchers may wish to review all potentially related categories and review the full descriptions for more details on the content of the records.

In several cases, different Department of Defense agencies used the same data systems, but may have modified the system to meet their needs. Therefore, NARA may have two versions or series of the same system. For example, both the Office of the Secretary of Defense (Record Group 330) and the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (records found in Record Group 472) transferred files from the Hamlet Evaluation System (HES). In general, besides the fact that difference agencies transferred the files, the versions may differ in time coverage, format, and/or layout. While the different versions may contain some of the same records, there may be records in one version that are not in the other and vice versa.

In general, besides the fact that difference agencies transferred the files, the versions may differ in time coverage, format, and/or layout. While the different versions may contain some of the same records, there may be records in one version that are not in the other and vice versa.

Full descriptions of the series and data files listed in this report are in the National Archives Catalog. Users can search the Catalog by title, National Archives Identifier, type of archival material, or keyword.

NARA also has custody of textual (paper) records related to some of the Vietnam War data files described in this reference report. Some of these records may include outputs from the systems and reports based on the data. Users may wish to search the National Archives Catalog for descriptions of any related textual (paper) records.

Some of the series and files listed in this report are accessible online:

All of the files are also available for a cost-recovery fee. For more information see: Ordering Information for Electronic Records.

For more information see: Ordering Information for Electronic Records.

Please note that NARA makes public use versions available of records containing personal identifiers that if released may result in an unwarranted invasion of privacy. Such public use versions mask or delete these sensitive personal identifiers. In general, records of deceased casualties are released in full. The description and/or the technical documentation for a series outlines the information masked in the public use version.

Data about Military Operations, Incidents, and Activities

Record Group 218: Records of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff

- Terrorist Incident Reporting System (TIRSA), ca. 10/01/1967 – ca. 06/30/1972

National Archives Identifier: 7423670

Data Files: 1 (NIPS)

Technical Documentation: 10 pagesThis series contains data on Viet Cong (VC) incidents against South Vietnam (SVN) indigenous civilian population plus damage or destruction of private or government property and /or installations.

These files came from Headquarters, Pacific Command (PACOM) via the Survivability/Vurnerability Information Analysis Center (SURVIAC) [Wright-Paterson Air Force Base].

These files came from Headquarters, Pacific Command (PACOM) via the Survivability/Vurnerability Information Analysis Center (SURVIAC) [Wright-Paterson Air Force Base].

Record Group 330: Records of the Office of the Secretary of Defense

- Terrorist Incident Reporting System (TIRSA) Files, 10/1967 – 2/1973

National Archives Identifier: 5956273

Data Files: 1 (de-NIPS’d)

Technical Documentation: 44 pages

Online Access: DownloadThis series consists of records of Viet Cong and North Vietnamese initiated incidents of violence against the civilian population of South Vietnam during the Vietnam War. TIRSA is part of the Operations Analysis (OPSANAL) system.

Record Group 472: Records of the U.S. Forces in Southeast Asia

- Psychological Operations Information System (PSYOPSIS) Files, 3/1970 – 2/1973

National Archives Identifier: 23812710

Data Files: 5 (ASCII Rendered) (NIPS version available)

Technical Documentation: 90 pages

Online Access: DownloadThis series contains records about aerial and surface psychological operations carried out by the U.

S. military during the Vietnam War. This data served as input for the Psychological Operation Quarterly Analysis System (PSYOPQA).

S. military during the Vietnam War. This data served as input for the Psychological Operation Quarterly Analysis System (PSYOPQA).

- Psychological Operation Quarterly Analysis System (PSYOPQA) Files, 3/1970 – 2/1973

National Archives Identifier: 23812489

Data Files: 3 (EBCDIC)

Technical Documentation: 45 pagesThis series contains aggregate data about psychological operations carried out by the U.S. military during the Vietnam War. The data from the Psychological Operations Information System (PSYOPSIS) served as input for this series. The data was linked with selected data from the Hamlet Evaluation System (HES).

- Terrorist Incident Reporting System (TIRS), 6/1968 – 2/1973

National Archives Identifier: n/a

Data Files: 3 (EBCDIC)

Technical Documentation: estimated 20 pages basic documentation; estimated 285 pages full documentationThis series contains data about incidents by the enemy against the civilian population, and public and private property.

Incidents captured in the system include deaths, abductions, seizure of property, damage to property, and injuries, to name a few. This system was used as input for “Terrorist Incident Reporting System (TIRSA) Files, 10/1967 – 2/1973.”

Incidents captured in the system include deaths, abductions, seizure of property, damage to property, and injuries, to name a few. This system was used as input for “Terrorist Incident Reporting System (TIRSA) Files, 10/1967 – 2/1973.”

Data specific to Land Military Operations and Activities

Record Group 218: Records of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff

- Records About the Ground Combat Operations by the Army During the Vietnam War, 5/20/1966 – 3/12/1973 (also known as Situation Report Army (SITRA))

National Archives Identifier: 604416

Data Files: 4 (ASCII translated) (NIPS versions available)

Technical Documentation: 49 pages, 2 electronic documentation files

Online Access: Download SearchThis series contains records of ground combat operations in Southeast Asia during the Vietnam War, and includes but is not limited to information on the type of military operation, nationalities of armed forces, location, and dates.

- FO System Data Files, ca. 01/01/1963 – ca. 06/30/1970

National Archives Identifier: 7451157

Data Files: 11 (NIPS)

Technical Documentation: 4 pages (no angency documentation)This series includes statistical operations data about friendly initiated (FO) incidents and actions in Southeast Asia during the Vietnam War. It appears this series may conain data from the Republic of Vietnam Operational Statistics System (RVNOSS). These files came from Headquarters, Pacific Command (PACOM) via the Survivability/Vulnerability Information Analysis Center (SURVIAC) [Wright-Patterson Air Force Base].

- VC System Data Files, ca. 01/01/1962 – ca. 08/31/1971

National Archives Identifier: 7423976

Data Files: 18 (NIPS)

Technical Documentation: 4 pages (no agengy documentation)This series includes operations data about enemy initiated (VC) incidents and actions in Southeast Asia during the Vietnam War.

It appears this series may contain data from the Republic of Vietnam Operational Statistics System (RVNOSS). These files came from Headquarters, Pacific Command (PACOM) via the Survivability/Vulnerability Information Analysis Center (SURVIAC) [Wright-Patterson Air Force Base].

It appears this series may contain data from the Republic of Vietnam Operational Statistics System (RVNOSS). These files came from Headquarters, Pacific Command (PACOM) via the Survivability/Vulnerability Information Analysis Center (SURVIAC) [Wright-Patterson Air Force Base].

Record Group 330: Records of the Office of the Secretary of Defense

- Enemy Base Area File (BASFA), 7/1/1967 – 6/1/1971

National Archives Identifier: 600139

Data Files: 1 (ASCII translated) (NIPS version available)

Technical Documentation: 40 pages

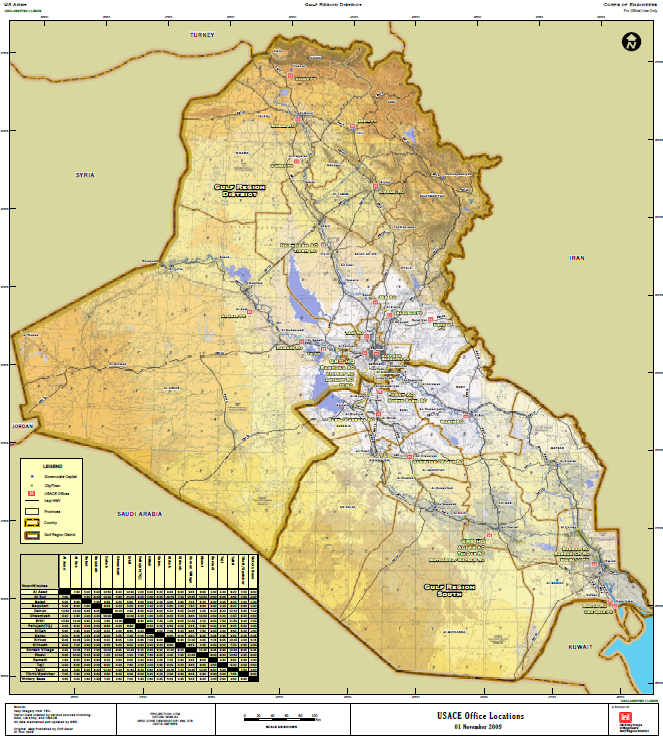

Online Access: Download SearchThis series contains data that define enemy base area locations in South Vietnam, North Vietnam, and Cambodia on a monthly basis. BASFA is part of the Operations Analysis (OPSANAL) system.

- Southeast Asia Friendly Forces File (SEAFA), 10/1966 – 7/1972

National Archives Identifier: 602104

Data Files: 1 (de-NIPS’d)

Technical Documentation: 38 pages

Online Access: DownloadThis series contains information on the identity and location of American, South Vietnamese, and Allied maneuver battalions (infantry, armored, cavalry, airborne, and air mobile) deployed in Southeast Asia during the Vietnam War.

SEAFA is part of the Operations Analysis (OPSANAL) system.

SEAFA is part of the Operations Analysis (OPSANAL) system.

- Vietnam Database (VNDBA) Files, 1/1963 – 12/1969

National Archives Identifier: 5927921

Data Files: 9 (NIPS and/or de-NIPS’d)

Technical Documentation: 68 pagesThis series contains data on ground combat operations, whether enemy or friendly initiated, in South Vietnam during the Vietnam War. VNDBA is part of the Operations Analysis (OPSANAL) system.

Record Group 335: Records of the Office of the Secretary of the Army

- Battalion Tracking Study Files, 10/1/1966 – 3/31/1969

National Archives Identifier: 644345

Data Files: 55 (ASCII)

Technical Documentation: 61 pages

Online Access: DownloadThis series contains data for 48 U.S. Army ground combat battalions that were located in III Corps during the Vietnamese Conflict. The data was compiled as part of a study on the exposure of U.

S. Army personnel to Agent Orange. It was created in conjunction with the series “Vietnam Experience Study Files, 1967 – 1968” (see Data about U.S. Military Personnel).

S. Army personnel to Agent Orange. It was created in conjunction with the series “Vietnam Experience Study Files, 1967 – 1968” (see Data about U.S. Military Personnel).

Record Group 338: Records of U.S. Army Operational, Tactical, and Support Organizations

- Records About Combat Operations by Army Units and Their Use and Loss of Military Supplies During the Vietnam War (COLED-V), 7/1/1967 – 6/30/1970

National Archives Identifier: 572881

Data Files: 6 (ASCII)

Technical Documentation: 32 pages

Online Access: Download SearchThese records contain information about the use and the loss of military supplies, such as ammunition and equipment, by unit and by type of combat activity during the Vietnam War.

Record Group 472: Records of the U.S. Forces in Southeast Asia

Data specific to Air Military Operations and Activities

Record Group 218: Records of the U. S. Joint Chiefs of Staff

S. Joint Chiefs of Staff

- Combat Air Activities Files (CACTA), 10/1965 – 12/1970

National Archives Identifier: 634496

Data Files: 32 (ASCII Translated) (NIPS version available)

Technical Documentation: 160 pages and 2 electronic layout files

Online Access: Download SearchThis series contains bimonthly data on air combat missions flown in Southeast Asia by U.S. and allied forces during the first part of the Vietnam War. It is the predecessor to the series “Records About Air Sorties Flown in Southeast Asia, 1/1970 – 6/1975.” These CACTA files contain two months of data, with some gaps. There is some duplication between these CACTA files and those in Record Group 529 and there are some records in one version that are not in the other and vice versa.

- Combat Air Activities (COACT) System Files, ca. 04/01/1969 – ca. 01/31/1970

National Archives Identifier: 7451124

Data Files: 2 (NIPS)

Technical Documentation: 1,993 pagesThis series contains data on Fixed-Wing Aircraft Combat and Combat Support Sorties for U.

S. and South Vietnam military forces. These files came from Headquarters, Pacific Command (PACOM) via the Survivability /Vulnerability Information Analysis Center (SURVIAC) [Wright-Patterson Air Force Base].

S. and South Vietnam military forces. These files came from Headquarters, Pacific Command (PACOM) via the Survivability /Vulnerability Information Analysis Center (SURVIAC) [Wright-Patterson Air Force Base].

- Combat Air Summary Files (OPREA), 1/31/1962 – 8/15/1973

National Archives Identifier: 625084

Data Files: 84 (ASCII Rendered) (NIPS version available)

Technical Documentation: 121 pages and 11 electronic layout files

Online Access: DownloadThis series contains data on air warfare missions flown over Southeast Asia during the Vietnam War. NARA received three files from the U.S. Joint cheifs of Staff via the National Military Command Systems Support Center and nine files from Headquarters, Pacific Commaand (PACOM) via the Survivability/Vulnerability Information Analysis Center (SURVIAC) [Wright-Patterson Air Force Base]. There may be some duplication between the sets of files.

- Records About Air Sorties Flown in Southeast Asia, 1/1970 – 6/1975 (also known as Southeast Asia Database (SEADAB))

National Archives Identifier: 602566

Data Files: 23 (ASCII Translated) (NIPS version also available)

Technical Documentation: 118 pages and 1 electronic layout file

Online Access: Download SearchThis series consists of files with records on air combat missions flown in Southeast Asia by U.

S. and allied forces during the last part of the Vietnam War. It is the successor to the series “Combat Air Activities Files (CACTA), 10/1965 – 12/1970.”

S. and allied forces during the last part of the Vietnam War. It is the successor to the series “Combat Air Activities Files (CACTA), 10/1965 – 12/1970.”

Record Group 330: Records of the Office of the Secretary of Defense

- Herbicide File, 1965 – 1971

National Archives Identifier: 623176

Data Files: 4 versions: Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) de-NIPS’d version; NARA de-NIPS’d version; National Academy of Science (NAS) version; and Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) Revised version

Technical Documentation: 70 pages

Online Access: DownloadThis series contains data on herbicide spraying missions, including the use of Agent Orange, during the Vietnam War.

Record Group 341: Records of Headquarters U.S. Air Force (Air Staff)

- Airlift Operations Data Files, 10/1/1966 – 4/30/1972

National Archives Identifier: 630623

Data Files: 140 (ASCII Rendered) for ALOREP; 85 (ASCII Rendered) for MACAL; (NIPS version available for ALOREP and MACAL)

Technical Documentation: 18 pages and 2 electronic documentation files for ALOREP; 14 pages and 3 electronic documentation files for MACAL

Online Access: Download

This series contains sortie-level data on the operational employment of airlift resources during the Vietnam War. The series includes the Airlift Operations Files (ALOREP) and Military Airlift Command Airlift Operations Report (MACAL) files.

The series includes the Airlift Operations Files (ALOREP) and Military Airlift Command Airlift Operations Report (MACAL) files.

Record Group 529: Records of U.S. Pacific Command

- Combat Air Activities Files (CACTA), 10/1/1965 – 1/31/1971

National Archives Identifier: 2123846

Data Files: 50 (ASCII Translated) (NIPS version also available)

Technical Documentation: 50 pages NARA prepared documentation, 1 electronic layout file (for agency documentation see CACTA RG 218)

Online Access: DownloadThis series contains monthly data on air combat missions flown in Southeast Asia by U.S. and allied forces. These CACTA files are mostly by month, with some gaps. There is some duplication between these CACTA files and those in Record Group 218 and there are some records in one version that are not in the other and vice versa.

- Southeast Asia Imagery Reconnaissance Files (SIRFA), 5/5/1971 – 5/13/1975

National Archives Identifier: 630982

Data Files: 1 data file (EBCDIC)

Online Access: Download

Technical Documentation: 18 pages and 1 electronic documentation file (EBCDIC)This series contains data identifying reconnaissance objectives, imagery requests, and imagery characteristics for imagery reconnaissance missions flown over Southeast Asia during the Vietnam War.

Data specific to Sea Military Operations and Activities

See also Data specific to Air Military Operations and Activities for Navy air sorties

Record Group 38: Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations

Record Group 218: Records of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff

- Mine Warfare Operations Files (MINEA), 5/9/1972 – 1/14/1973

National Archives Identifier: 630554

Data Files: 2 (ASCII Rendered) (NIPS version available)

Technical Documentation: 49 pages and 1 electronic layout file

Online Access: Download SearchThis series contains data from two military operations during the Vietnamese Conflict, Operation Linebacker and Operation Pocket Money, which concerned all mining operations conducted against North Vietnamese interior waterways and harbors.

Data specific to Tactical Military Intelligence

Record Group 472: Records of the U. S. Forces in Southeast Asia

S. Forces in Southeast Asia

Data about U.S. Military Personnel

Series containing data on U.S. military casualties are described in a separate reference report, Records of U.S. Military Casualties, Missing in Action, and Prisoners of War from the Era of the Vietnam War.

Record Group 335: Records of the Office of the Secretary of the Army

- Vietnam Experience Study Files, 1967 – 1968

National Archives Identifier: 648567

Data Files: 8 (ASCII)

Technical Documentation: 72 pages

Online Access: DownloadThis series contains data on selected Army personnel who served in the Vietnamese conflict during 1967 and 1968 and were assigned to units tracked in the series “Battalion Tracking Study File, 10/1/1966 – 3/31/1969” (see Data specific to Land Military Operations and Activities). Public use versions of the files are available.

Record Group 472: Records of the U. S. Forces in Southeast Asia

S. Forces in Southeast Asia

- Records of Awards and Decorations of Honor During the Vietnam War (also known as Awards and Decorations System (AWADS))

National Archives Identifier: 604413

Data Files: 1 (ASCII)

Technical Documentation: 131 pages

Online Access: Download SearchThis series contains information about some of the awards and decorations of honor awarded to U.S. military officers, soldiers, and sailors, and to allied foreign military personnel. A public use version is available.

Data about Vietnamese and Allied Military Forces

Record Group 218: Records of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff

- Southeast Asia Casualty File (SEACA), 1/27/1973 – 4/20/1975

National Archives Identifier: 630221

Data Files: 1 (NIPS)

Technical Documentation: 16 pages

Online Access: DownloadThis series contains counts of the number of war casualties during the ceasefire period.

Casualty counts include South Vietnam civilians, Army of the Republic of Vietnam forces, North Vietnamese Army, and Viet Cong.

Casualty counts include South Vietnam civilians, Army of the Republic of Vietnam forces, North Vietnamese Army, and Viet Cong.

Record Group 330: Records of the Office of the Secretary of Defense

- Cambodian Friendly Units Files, 1/1970 – 3/1973

National Archives Identifier: 610063

Data Files: 1 (ASCII Translated) (NIPS version available)

Technical Documentation: 32 pages and 1 documentation (layout) file

Online Access: Download SearchThis series contains data on over 900 military units in the Cambodian Armed Forces (Forces Armees Nationales Khmeres (FANK)) that were friendly to the allied side during the Cambodian War and the Vietnam War.

- Army and Marine Forces of the Republic of South Vietnam Evaluation Files, 1/1969 – 1/1971

National Archives Identifier: 609212

Data Files: 3 (NIPS) for AMFESMA; 1 (NIPS) for AMFSA

Technical Documentation: estimated 200 pagesAlso known as the Army and Marine Forces Evaluation System Monthly Activity (AMFESMA), this series contains monthly activity data on the effectiveness of the armed forces of the Republic of South Vietnam.

AMFESMA was part of the System to Evaluate the Effectiveness of the Republic of Vietnam Forces (SEER). There is an additional file, Army and Marine Forces Monthly Activity (AMFSA), that covers 1968.

AMFESMA was part of the System to Evaluate the Effectiveness of the Republic of Vietnam Forces (SEER). There is an additional file, Army and Marine Forces Monthly Activity (AMFSA), that covers 1968.

- Territorial Forces Activity Reporting System (TFARS) Files, 9/1972 – 4/1974

National Archives Identifier: 617479

Data Files: 1 (NIPS) for 1972 file; 1 (de-NIPS’d) for 1973 file

Technical Documentation: estimated 86 pagesThis series contains information relating to personnel, training, unit deployment, military readiness, and operations of Vietnam Armed Forces. It is the predecessor to the series “Monthly Reports of Vietnamese Regional and Popular Forces, 4/1970 – 9/1972.”

Record Group 472: Records of the U.S. Forces in Southeast Asia

- Monthly Reports of Vietnamese Regional and Popular Forces, 4/1970 – 9/1972

National Archives Identifier: 598773

Data Files: 1 (EBCDIC) for TFES; 1 (EBCDIC) for VNUS

Technical Documentation: 66 pages

Online Access: DownloadThis series consists of the Territorial Forces Evaluation System (TFES) and Vietnamese/United States System (VNUS).

Both systems contain data on the combat effectiveness of regional and popular forces with South Vietnam. These systems were merged and expanded into the “Territorial Forces Analysis Reporting System (TFARS) Files, 9/1972 – 4/1974.”

Both systems contain data on the combat effectiveness of regional and popular forces with South Vietnam. These systems were merged and expanded into the “Territorial Forces Analysis Reporting System (TFARS) Files, 9/1972 – 4/1974.”

- Peoples Self-Defense Force / Management Information System (PSDF/MIS), 2/1972 – 8/1972

National Archives Identifier: 182794193

Data Files: 1 (ASCII)

Technical Documentation: 98 pages

Online Access: DownloadThis series contains information on local defense forces, such as the number of people in combat training, the number and type of weapons in each hamlet, the number of friendly and enemy casualties, the training status of defense units, and if the defense unit engaged in combat, along with demographic information. The agency used the data to evaluate the progress and effectiveness of various components of local defense forces.

Data related to Intelligence Gathering and Pacification Efforts

Record Group 330: Records of the Office of the Secretary of Defense

- Hamlet Evaluation System (HES) Files, 1967 – 1974

National Archives Identifier: 4616225

Data Files: 98 (ASCII Rendered) (de-NIPS’d and NIPS version available)

Technical Documentation: varies per file(s) (343 pages total, plus supplemental documentation)

Online Access: DownloadThis series contains geopolitical and demographic information for South Vietnamese villages and hamlets, along with observation ratings relating to security conditions and socio-economic factors in each village and hamlet.

- Pacification Attitude Analysis System (PAAS) Files, 3/1970 – 7/1972

National Archives Identifier: 29011649

Data Files: 3 versions: Original NIPS file; De-NIPS’d file with one record per question; and De-NIPS’d file with one record per respondent

Technical Documentation: estimated 400 pagesThis series contains monthly public opinion poll responses from Vietnamese interviewees in both rural and urban areas about the Vietnamese Conflict, Cambodian War, Pacification Program, economic conditions, and other public issues. Interviewers memorized the survey questions, used indirect questioning techniques to obtain the responses, and then memorized the responses.

Record Group 472: Records of the U.S. Forces in Southeast Asia

- Hamlet Evaluation System (HES), 1969 – 1973

National Archives Identifier: 18556191

Data Files: 1 (EBCDIC, variable-length records)

Technical Documentation: none compiledThis series contains geopolitical and demographic information for South Vietnamese villages and hamlets, along with observation ratings relating to security conditions and socio-economic factors in each village and hamlet.

- South Vietnamese National Police Force Counterinsurgency Files, 1971 – 1973

National Archives Identifier: 609777

Data Files: 2 (ASCII)

Technical Documentation: 40 pages for the data files; 4 electronic documentation files and 84 pages for the documentation files; 1 program source file

Online Access: DownloadThis series contains two subsystems of the National Police Infrastructure Analysis Subsystems (NPIASS I and NPIASS II) that have information about Viet Cong (VC) infrastructure by position and name, and document by dossier suspected VC members and the countermeasures taken against each suspect. A public use version of NPIASS II is available.

This series also contains the following electronic documentation files:

- Hamlet Evaluation System (HES) / Viet Cong Infrastructure (VCI) Gazetteer, 1971-1973

- Hamlet Evaluation System (HES) Gazetteer Source File, 1971-1973

- Hamlet Evaluation System (HES) Gazetteer, 1971-1973

- Greenbook File

The gazetteer files include codes and names for the geographic levels of Province, District, Village, and/or Hamlet, along with codes for the Corps Region, population numbers, ratings, and Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) coordinates.

The files may serve as the source for the meanings for the district, village, and hamlet codes used in Hamlet Evaluation System (HES) and other related Vietnam War data files. The Greenbook file contains a table of all Viet Cong Infrastructure (VCI) political position codes, position title, and reporting level indicators.

The files may serve as the source for the meanings for the district, village, and hamlet codes used in Hamlet Evaluation System (HES) and other related Vietnam War data files. The Greenbook file contains a table of all Viet Cong Infrastructure (VCI) political position codes, position title, and reporting level indicators.

- Pacification Attitude Analysis System (PAAS) File, 1/1970 – 2/1973

National Archives Identifier: 631425

Data Files: 1 (EBCDIC)

Technical Documentation: estimated 1,300 pagesThis series contains monthly public opinion poll responses from Vietnamese interviewees in both rural and urban areas about the Vietnamese Conflict, Cambodian War, Pacification Program, economic conditions and other public issues. Interviewers used memorized the survey questions, used indirect questioning techniques to obtain the responses, and then memorized the responses.

- Viet Cong Biographical File, 1/1969 – 6/1972

National Archives Identifier: 609857

Data Files: 1 (EBCDIC)

Technical Documentation: 86 pages (192 pages supplemental)

Online Access: DownloadAlso known as the Phung Hoang Management Information System (PHMIS), this file contains biographical data on all suspected or confirmed members of the Viet Cong.

A public use version is available.

A public use version is available.

Data related to Logistics

Record Group 472: Records of the U.S. Forces in Southeast Asia

Output Formats

Contact staff for more details about specific files

NIPS

During the Vietnam War, the Department of Defense used an early data base management system called the National Military Command System (NMCS) Information Processing System 360 Formatted File System, commonly known as NIPS. The International Business Machines Corporation (IBM) developed the system. NIPS allowed users the ability to structure files, generate and maintain files, revise and update data, select and retrieve data, and generate reports. In some ways, NIPS supported relational database functionality.

Department of Defense agencies transferred to NARA many of the data files created during the Vietnam War in the software-dependent NIPS format. Although most of the file contains data, the beginning of the file consists of supporting information used during file maintenance, data retrieval, and output processing. The data are composed of fixed, non-repeating data with repeating subsets (i.e. a one-to-many relationship). The data are organized into the following sets of elements or tables:

The data are composed of fixed, non-repeating data with repeating subsets (i.e. a one-to-many relationship). The data are organized into the following sets of elements or tables:

- Control Set, containing the unique record identifier that links to the Fixed Set and Periodic Sets;

- Fixed Set, containing non-repetitive data; and

- Periodic Sets, containing fields that can be repeated as needed; there can be more than one type of Periodic Set.

For example, a record for a military mission in a NIPS file would include a control set that contains a unique identifier or fields that can be combined to create a unique identifier; a fixed set with data about the mission as a whole; a periodic set with data about the ordnance used in the mission that would be repeated for each type of ordnance used in the mission; and a periodic set about the losses incurred in the mission repeated for each type of loss incurred. Therefore, a single mission record would consist of the control set, fixed set, none-to-many periodic sets per ordnance, and none-to-many periodic sets per loss.

In addition, NIPS files can include Variable Sets that appear only when data is present. These sets are usually “Comments” data in a free-text field of variable length. Data records in NIPS files are usually of varying length since the number of periodic sets vary for each record. NARA only provides exact copies of NIPS files.

De-NIPS’d

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, NARA staff “de-NIPS’d” or reformatted some of the files transferred in the NIPS format, outputting the data in a flat-file format using then-standard EBCDIC encoding. This was done in order to have a software-independent version of the data. However the “de-NIPSing” process output some numeric fields in a zoned decimal format; these fields usually need to be reformatted before using with contemporary software.

In addition, the NIPS records have a control set, fixed set, and periodic set of fields. In the “de-NIPS’d” version, the control set or the fixed set of fields may appear in the first instance of the record, but may not appear in the subsequent instances with multiple periodic set fields for that record, which immediately follow the first instance. For example, the first instance of a record would be a row in the database containing the control set, fixed set, and the first periodic set. If there are multiple periodic sets for that record, the next row would only include the control set and the second periodic set, followed by another row with the control set and the third periodic set, and so forth for each periodic set. Therefore the records are preserved in a specific sequential order and need to be “read” by the computer in that order. “De-NIPS’d” files may contain fixed-length or variable-length records. NARA only provides exact copies of de-NIPS’d files.

For example, the first instance of a record would be a row in the database containing the control set, fixed set, and the first periodic set. If there are multiple periodic sets for that record, the next row would only include the control set and the second periodic set, followed by another row with the control set and the third periodic set, and so forth for each periodic set. Therefore the records are preserved in a specific sequential order and need to be “read” by the computer in that order. “De-NIPS’d” files may contain fixed-length or variable-length records. NARA only provides exact copies of de-NIPS’d files.

ASCII Translated

In 2002, NARA staff and volunteers developed computer programs written in Common Business-Oriented Language (COBOL) to translated the NIPS files into ASCII, fixed-length records per each periodic set that contained the control set, fixed set, and periodic set fields. This format allows users to sort the records (i.e. the records are no longer in a sequential order).

ASCII Rendered

In 2007, NARA staff developed another software program, NIPSTRAN, to convert the NIPS files into more usable ASCII rendered tables. The program produces a table for the fixed set and tables for each periodic set. The tables function like a relational-database with one-to-many relationship (i.e. one fixed set record to many periodic set records). All the records in the tables include the corresponding control set fields to allow for linking between the fixed set table and periodic set table(s). The records in the tables are fixed-length and there may be versions of the tables where the records are field delimited.

EBCDIC and/or Binary

If not in the NIPS format, most of the other Vietnam War data files in NARA’s custody are preserved in EBCDIC encoding. Some of these files may include binary characters, fields with zoned decimal data, variable-length records with binary counters, or other aspects that require the file be reformatted before using with contemporary software and may not properly auto-convert to ASCII. NARA can only offer exact copies of these files.

NARA can only offer exact copies of these files.

Selected Supplemental Documentation

Civil Operations and Rural Development Support (CORDS), Research and Analysis Directorate, Hamlet Evaluation System (HES) Command Manual, Document No. DAR R70-79 CM-01B, Military Assistance Command Vietnam, 1 September 1971. (RG 472; 108 pages)

Civil Operations and Rural Development Support (CORDS), Research and Analysis Directorate, Hamlet Evaluation System (HES) Operations Manual, Document No. DAR R70 OM-01A, Military Assistance Command Vietnam, June 1972. (RG 472; 150-200 pages)

Defense Communications Agency, Command and Control Technical Center, NMCS Information Processing System 306 Formatted File System (NIPS 360 FFS) General Description, Computer System Manual Number CSM GS 15-17, 1 September 1978. (41 pages)

Defense Communications Agency, Command and Control Technical Center, NMCS Information Processing System 306 Formatted File System (NIPS 360 FFS) Volume I Introduction to File Concepts, Computer System Manual Number CSM UM 15-78, 1 September 1978. (106 pages)

(106 pages)

National Military Command System Support Center, The Operation Analysis System (OPSANAL) User’s Manual (Revision A), Computer System Manual Number CSM UM63A-68, 30 September 1969. (405 pages)

Selected Additional Resources

Adams, Margaret O. “Vietnam Records in the National Archives: Electronic Records.” Prologue 23 (Spring 1991): 76-84.

Campbell, Curt. “Essay on the Potential Research Value of the OPSANAL System Files,” July 1996.

Carter, G. A., et al. An Interim Guide to Southeast Asia Combat Data. Prepared for the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency by Rand (WN-8718-ARPA). Santa Monica, CA: Rand, June 1974.

Carter, G. A., et al. A User’s Guide to Southeast Asia Combat Data. Prepared for the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency by Rand (R-1815-ARPA). Santa Monica, CA: Rand, June 1976.

Electronic Records Reference Report, Records of U.S. Military Casualties, Missing in Action, and Prisoners of War from the Era of the Vietnam War

Eliot, Duong Van Mai. RAND in Southeast Asia: a history of the Vietnam War era. Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2010.

RAND in Southeast Asia: a history of the Vietnam War era. Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2010.

Harrison, Donald F. “Computers, Electronic Data, and the Vietnam War.” Archivaria 26 (Summer 1988): 18-26.

Harrison, Donald F. “Machine-Readable Sources for the Study of the War in Vietnam.” In Databases in the Humanities and Social Sciences-4: Proceedings of the International Conference on Databases in the Humanities and Social Sciences, July, 1987, ed. Lawrence J. McCrank. Medford, NJ: Learned Information, Inc, 1989.

Hull, Theodore J. “Electronic Records of Korean and Vietnam Conflict Casualties,” Prologue, 32 (Spring 2000).

NARA Reference Information Paper 90, Records Relating to American Prisoners of War and Missing in Action from the Vietnam War Era, 1960-1994

Thayer, Thomas C., ed. A System Analysis View of the Vietnam War: 1965-1972, 12 volumes, 1975. These volumes contain articles printed in the “Southeast Asia Analysis Report” from January 1967 to January 1972. The volumes include:

The volumes include:

- Volume 1 – The Situation in Southeast Asia

- Volume 2 – Forces and Manpower

- Volume 3 – Viet Cong – North Vietnamese Operations

- Volume 4 – Allied Ground and Naval Operations

- Volume 5 – The Air War

- Volume 6 – Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces (RVNAF)

- Volume 7 – Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces (RVNAF)

- Volume 8 – Casualties and Losses

- Volume 9 – Population Security

- Volume 10 – Pactification and Civil Affairs

- Volume 11 – Economics: War Costs and Inflation

- Volume 12 – Construction and Port Operations in South Vietnam

Contact Information

Reference Services

Electronic Records

National Archives at College Park

8601 Adelphi Road

College Park, MD 20740-6001

(301) 837-0470

Email: [email protected]

May 2021

Electronic Records Main Page

Battlefield Surveillance – an overview

INTRODUCTION TO RADAR

Radar is an electromagnetic sensor that greatly extends one’s ability to detect reflecting objects (or targets) at long or short range and to accurately locate targets in fair, as well as poor weather. Since its introduction during the second world war, radar has been a vital part of air defense in its many forms and for other military missions such as battlefield surveillance, fighter/attack aircraft, ballistic missile defense, and antisubmarine warfare. It has also been important for many nonmilitary applications including weather observation (precipitation, severe storms, winds, and wind shear), observing beneath the ever-present clouds of a planet like Venus, probing below the surface of the Earth, high-resolution imaging of the Earth’s surface in three dimensions, and for mapping of sea ice for the more efficient routing of shipping in northern regions. Targets of interest to radar have been aircraft, ships, missiles, spacecraft, vehicles, people, birds, insects, as well as the natural environment.

Since its introduction during the second world war, radar has been a vital part of air defense in its many forms and for other military missions such as battlefield surveillance, fighter/attack aircraft, ballistic missile defense, and antisubmarine warfare. It has also been important for many nonmilitary applications including weather observation (precipitation, severe storms, winds, and wind shear), observing beneath the ever-present clouds of a planet like Venus, probing below the surface of the Earth, high-resolution imaging of the Earth’s surface in three dimensions, and for mapping of sea ice for the more efficient routing of shipping in northern regions. Targets of interest to radar have been aircraft, ships, missiles, spacecraft, vehicles, people, birds, insects, as well as the natural environment.

Radar operates by radiating from an antenna, a known waveform, usually a series of short-duration pulses. After a portion of the radiated energy is reflected by a target and returned to the radar, it is received by the antenna and processed in the receiver to detect the presence of a target and to determine something about its nature. Two of the basic measurements made by a radar are range (distance) and angular location of a target. By observing the location of a target over time, the radar can establish its trajectory, or track, and predict the target’s future location. Many modern radars use to advantage the shift in frequency (relative to the frequency that was transmitted) of the echo signal from a moving target. The shift of the echo signal frequency from a moving target is caused by the doppler effect, something familiar from high school or college physics. The doppler frequency shift is proportional to the radial velocity of the target, so it can be used to separate the frequency-shifted signals from moving targets (such as aircraft) from large undesired stationary clutter echo signals from the land, sea, and weather. It is an important part of MTI (moving target indication), pulse doppler, and CW (continuous wave) radars that have to detect small moving targets in the midst of very large clutter echoes.

Two of the basic measurements made by a radar are range (distance) and angular location of a target. By observing the location of a target over time, the radar can establish its trajectory, or track, and predict the target’s future location. Many modern radars use to advantage the shift in frequency (relative to the frequency that was transmitted) of the echo signal from a moving target. The shift of the echo signal frequency from a moving target is caused by the doppler effect, something familiar from high school or college physics. The doppler frequency shift is proportional to the radial velocity of the target, so it can be used to separate the frequency-shifted signals from moving targets (such as aircraft) from large undesired stationary clutter echo signals from the land, sea, and weather. It is an important part of MTI (moving target indication), pulse doppler, and CW (continuous wave) radars that have to detect small moving targets in the midst of very large clutter echoes. The doppler shift is also the basis for meteorological radars that detect and recognize hazardous weather effects to provide information about the environment not readily available by other means. In addition to the usual measurements of range, angular location, relative velocity, and target track, radar sometimes can obtain information about the size, shape, symmetry, and surface properties of a target.

The doppler shift is also the basis for meteorological radars that detect and recognize hazardous weather effects to provide information about the environment not readily available by other means. In addition to the usual measurements of range, angular location, relative velocity, and target track, radar sometimes can obtain information about the size, shape, symmetry, and surface properties of a target.

A simple block diagram illustrating the major subsystems of a radar that might be used for air surveillance is shown in Fig. 1. The transmitter is usually a power amplifier such as a klystron, traveling wave tube, or transistor. Although the magnetron oscillator was widely used in the early days of radar, its limited average-power, poor stability, and inability to generate sophisticated modulated waveforms restrict its application to radars with only modest capability. The first stage of the receiver is often a low-noise transistor amplifier. In a superheterodyne receiver, the echo is converted by a mixer and local oscillator (not shown) to an intermediate frequency (IF), where the signal is amplified and subject to signal processing to extract the desired signal and reject or attenuate undesired signals and noise. An important example of a signal processor is the matched filter that maximizes the ratio of the peak-signal-to-mean-noise output of the receiver, which in turn maximizes the detectability of the desired signal. In a receiver with a matched filter, the peak-output-signal-to-mean-noise-power ratio is 2E/N0, where E = signal energy and N0 = noise power per unit bandwidth. Thus detectability of a radar signal when a matched filter is used does not depend on the shape of the signal or its bandwidth, but only on its total energy. The detector stage following the IF stage extracts the signal modulation from the carrier frequency. In a radar where there are no undesired clutter echoes to compete with the detection of the desired target echoes, the detector stage is an envelope detector (also called the second detector). In a radar that employs the doppler frequency shift to separate (by the use of filters) desired moving targets from undesired fixed clutter echoes, the detector stage is a phase detector.

An important example of a signal processor is the matched filter that maximizes the ratio of the peak-signal-to-mean-noise output of the receiver, which in turn maximizes the detectability of the desired signal. In a receiver with a matched filter, the peak-output-signal-to-mean-noise-power ratio is 2E/N0, where E = signal energy and N0 = noise power per unit bandwidth. Thus detectability of a radar signal when a matched filter is used does not depend on the shape of the signal or its bandwidth, but only on its total energy. The detector stage following the IF stage extracts the signal modulation from the carrier frequency. In a radar where there are no undesired clutter echoes to compete with the detection of the desired target echoes, the detector stage is an envelope detector (also called the second detector). In a radar that employs the doppler frequency shift to separate (by the use of filters) desired moving targets from undesired fixed clutter echoes, the detector stage is a phase detector. It requires a reference signal (not shown) that is a faithful representation of the transmitted signal so as to recognize that the echo signal has experienced a doppler shift. A video amplifier (not shown) following the detector amplifies the signal and a decision is made whether the receiver output is due to a target (signal plus noise) or is due to noise alone. The detection decision is based on observing when the receiver output exceeds a predetermined threshold whose level depends on achieving an acceptable probability of false alarm. In early radars the detection decision was made by an operator viewing a radar display, but in modern radars the decision whether or not a target has been detected is made automatically without direct operator intervention.

It requires a reference signal (not shown) that is a faithful representation of the transmitted signal so as to recognize that the echo signal has experienced a doppler shift. A video amplifier (not shown) following the detector amplifies the signal and a decision is made whether the receiver output is due to a target (signal plus noise) or is due to noise alone. The detection decision is based on observing when the receiver output exceeds a predetermined threshold whose level depends on achieving an acceptable probability of false alarm. In early radars the detection decision was made by an operator viewing a radar display, but in modern radars the decision whether or not a target has been detected is made automatically without direct operator intervention.

Fig. 1. Simple block diagram of a generic radar system.

The received signal is digitized for processing, either after the detector stage (in the video) or before the detector (in the IF), especially in radars that depend on the doppler frequency shift for detection of moving targets. Digital processing makes it possible to automatically detect and accurately track many hundreds or thousands of targets so as to present fully processed tracks rather than individual detections or “raw” (unprocessed) radar data. The automatic tracker is an example of a data processor. The processed output of the radar or the established tracks of targets might be displayed to an operator or used to perform some automated operation. The antenna can be one of several different forms of mechanically steered parabolic reflectors, a mechanically steered planar array, or one of several types of electronically steered phased arrays. The duplexer is the device that allows a single antenna to be time-shared between the transmitter and the receiver.

Digital processing makes it possible to automatically detect and accurately track many hundreds or thousands of targets so as to present fully processed tracks rather than individual detections or “raw” (unprocessed) radar data. The automatic tracker is an example of a data processor. The processed output of the radar or the established tracks of targets might be displayed to an operator or used to perform some automated operation. The antenna can be one of several different forms of mechanically steered parabolic reflectors, a mechanically steered planar array, or one of several types of electronically steered phased arrays. The duplexer is the device that allows a single antenna to be time-shared between the transmitter and the receiver.

A typical long-range air-surveillance radar might have a resolution in the range dimension of about one or two hundred meters. When required, a radar can have a range resolution of a small fraction of a meter. The beamwidth of a radar antenna might typically be one or two degrees, but some operational radars have had beam widths as small as 0. 3 degree. Thus the resolution in the cross-range dimension (determined by the beamwidth and the target range) is usually much worse than the range resolution. It is possible, however, to achieve high resolution in the cross-range dimension comparable to the resolution achieved in the range dimension by employing synthetic aperture radar (SAR). Here the resolution of a large antenna is obtained by utilizing a small antenna on a moving platform, such as an aircraft, to store the received echoes over a relatively long time so as to synthesize (virtually) in a digital processor the equivalent of a large antenna. The output of a SAR is usually a high resolution map or image of a target scene.

3 degree. Thus the resolution in the cross-range dimension (determined by the beamwidth and the target range) is usually much worse than the range resolution. It is possible, however, to achieve high resolution in the cross-range dimension comparable to the resolution achieved in the range dimension by employing synthetic aperture radar (SAR). Here the resolution of a large antenna is obtained by utilizing a small antenna on a moving platform, such as an aircraft, to store the received echoes over a relatively long time so as to synthesize (virtually) in a digital processor the equivalent of a large antenna. The output of a SAR is usually a high resolution map or image of a target scene.

Radar is generally found within what is known as the microwave region of the electromagnetic spectrum from about 400 MHz to 40 GHz; but there have been many operational radars in the VHF region (30 to 300 MHz) as well as in the HF region (3 to 30 MHz). An HF over-the-horizon radar can reach out to ranges of about 2000 nmi by utilizing refraction from the ionosphere. Radar has also been considered for use at frequencies higher than the microwave region, at millimeter wavelengths. Laser radars are found in the IR and optical regions of the spectrum, where they can provide precision range and radial-velocity measurement.

Radar has also been considered for use at frequencies higher than the microwave region, at millimeter wavelengths. Laser radars are found in the IR and optical regions of the spectrum, where they can provide precision range and radial-velocity measurement.

3 The U.S. Military and the Herbicide Program in Vietnam | Veterans and Agent Orange: Health Effects of Herbicides Used in Vietnam

Gonzales J. 1992. List of Chemicals Used in Vietnam. Presented to the Institute of Medicine Committee to Review the Health Effects in Vietnam Veterans of Exposure to Herbicides. Illinois Agent Orange Committee, Vietnam Veterans of America.

Harrigan ET. 1970. Calibration Test of the UC-123K/A/A45Y-1 Spray System. Eglin AFB, FL: Armament Development and Test Center. Technical Report ADTC-TR-70-36. NTIS AD 867 004.

Heizer JR. 1971. Data Quality Analysis of the HERB 01 Data File. MITRE Technical Report, MTR-5105. Prepared for the Defense Communications Agency. McLean, VA: MITRE.

McLean, VA: MITRE.

Heltman LR. 1986. Veteran Population in the United States and Puerto Rico by Age, Sex, and Period of Service: 1970 to 1985. IM&S M70-86-6. Washington, DC: Veterans Administration, Office of Information Management and Statistics.

Huddle FP. 1969. A Technology Assessment of the Vietnam Defoliant Matter. Report to the Subcommittee on Science, Research, and Development of the Committee on Science and Astronautics, U.S. House of Representatives. 91st Cong., 1st sess. August 8, 1969 .

Irish KR, Darrow RA, Minarik CE. 1969. Information Manual for Vegetation Control in Southeast Asia. Misc. Publication 33. Fort Detrick, MD: Dept. of the Army, Plant Sciences Laboratories, Plant Physiology Division. NTIS AD 864 443.

Karnow S. 1991. Vietnam: A History. New York: Penguin.

Kulka RA, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA, Hough RL, Jordan BK, Marmar CR, Weiss DS. 1988. Contractual Report of Findings from the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute. Conducted for the Veterans Administration under contract number V101(93)P-1040.

Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute. Conducted for the Veterans Administration under contract number V101(93)P-1040.

Lewis WW. 1992. Herbicide Exposure Assessment. New Jersey Agent Orange Commission, Pointman II Project.

Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV). 1966. Evaluation of Herbicide Operations in the Republic of Vietnam as of 30 April 1966. MACV, Office of the Assistant Chief of Staff Intelligence. NTIS AD 779 792.

Military Assistance Command, Vietnam. 1968. The Herbicide Policy Review. Report for March-May 1968. APO San Francisco: MACV. NTIS AD 779 794/7. 140 pp.

Military Assistance Command, Vietnam. 1969a. Accidental Herbicide Damage . Vietnam Lessons Learned No. 74. APO San Francisco: MACV. September 15, 1969. NTIS AD 858-315-5XAB. 14 pp.

Military Assistance Command, Vietnam. 1969b. Military Operations: Herbicide Operations. APO San Francisco: MACV. August 12, 1969. NTIS AD 779 793. 20 pp.

Military Assistance Command, Vietnam. 1970. Command Manual for Herbicide Reporting System (HERBS). Document Number DARU07. NTIS AD 875 942.

1970. Command Manual for Herbicide Reporting System (HERBS). Document Number DARU07. NTIS AD 875 942.

Military Assistance Command, Vietnam. Military History Branch. 1972. Chronology of Events Pertaining to U.S. Involvement in the War in Vietnam and Southeast Asia.

Martin R. 1986. Who went to war. In: Boulanger G, Kadushin C, eds. The Vietnam Veteran Redefined: Fact and Fiction. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Midwest Research Institute (MRI). 1967. Assessment of Ecological Effects of Extensive or Repeated Use of Herbicides. MRI Project No. 3103-B. Kansas City, MO: MRI. NTIS AD 824 314.