How did East Coast Dyes become a prominent brand in lacrosse equipment. What makes the MINT Lacrosse Ball unique in the market. Why is East Coast Dyes’ trademark registration significant for the company’s growth.

The Rise of East Coast Dyes in the Lacrosse Industry

East Coast Dyes (ECD) has emerged as a significant player in the lacrosse equipment market, particularly known for their innovative MINT Lacrosse Ball. The company’s journey from a small partnership to a registered corporation reflects the growing demand for high-quality lacrosse gear.

ECD Lacrosse, Inc. successfully registered the trademark “EAST COAST DYES” with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) on July 24, 2018. This registration, bearing the number 5523322, marks a crucial milestone in the company’s branding efforts.

Key Details of the Trademark Registration

- Serial Number: 87703604

- Filing Date: November 30, 2017

- Published for Opposition: May 8, 2018

- Registration Date: July 24, 2018

- Mark Drawing: Standard character mark

Understanding the Scope of East Coast Dyes’ Trademark

The trademark registration covers International Class 028, which encompasses “Games and playthings; gymnastic and sporting articles not included in other classes; decorations for Christmas trees.” This broad classification allows ECD to protect its brand across various lacrosse-related products and accessories.

When did East Coast Dyes first use their trademark in commerce? According to the registration details, the company began using the mark as early as May 1, 2012, both in commerce and anywhere else. This early use date demonstrates the company’s long-standing presence in the lacrosse equipment market.

The Evolution of East Coast Dyes’ Business Structure

The trademark registration history reveals an interesting evolution in East Coast Dyes’ business structure:

- Original Applicant: East Coast Dyes (Partnership)

- Owner at Publication: East Coast Dyes (Partnership)

- Original Registrant: East Coast Dyes (Partnership)

- Current Owner: ECD LACROSSE, INC. (Corporation)

This progression from a partnership to a corporation suggests significant growth and formalization of the business over time. The change in legal entity type often indicates increased business complexity, potential for expansion, and a more structured approach to operations and governance.

The MINT Lacrosse Ball: A Game-Changing Product

While the trademark registration covers a broad range of sporting goods, East Coast Dyes has gained particular recognition for its MINT Lacrosse Ball. This product has set a new standard in the lacrosse equipment market.

Features of the MINT Lacrosse Ball

- Superior grip and consistency

- Enhanced durability compared to traditional lacrosse balls

- Unique mint color for improved visibility during play

- Meets official lacrosse regulations for size and weight

How does the MINT Lacrosse Ball differ from traditional lacrosse balls? The MINT ball is designed to maintain its grip and performance characteristics even in adverse weather conditions, addressing a common complaint among lacrosse players about balls becoming slick or unpredictable during play.

Impact of East Coast Dyes on Lacrosse Equipment Innovation

East Coast Dyes’ success with the MINT Lacrosse Ball and other products has spurred innovation across the lacrosse equipment industry. The company’s focus on addressing player needs and enhancing performance has set a new benchmark for quality and functionality in lacrosse gear.

What other products has East Coast Dyes developed? Beyond the MINT Lacrosse Ball, ECD has expanded its product line to include:

![]()

- Lacrosse heads with advanced string patterns

- High-performance lacrosse shafts

- Innovative stringing materials and tools

- Protective gear designed for maximum mobility and safety

The Significance of Trademark Protection in the Sporting Goods Industry

East Coast Dyes’ trademark registration highlights the importance of intellectual property protection in the competitive sporting goods market. By securing their brand name, ECD has:

- Established legal rights to their brand identity

- Created a foundation for brand recognition and loyalty

- Protected against potential infringement by competitors

- Increased the value of their business assets

Why is trademark protection crucial for sporting goods companies? In an industry where brand reputation and product recognition play significant roles in consumer choice, protecting a company’s name and logo is essential for maintaining market position and preventing consumer confusion.

East Coast Dyes’ Marketing and Brand Strategy

The successful registration and protection of the East Coast Dyes trademark have allowed the company to implement a cohesive marketing and brand strategy. This strategy likely includes:

- Consistent branding across all product lines

- Strategic partnerships with lacrosse teams and athletes

- Targeted advertising in lacrosse-specific media and events

- Social media engagement to build a community around the brand

How has East Coast Dyes leveraged its trademark to build brand loyalty? By consistently using their protected brand name and logo, ECD has created a recognizable presence in the lacrosse community, fostering trust and loyalty among players, coaches, and fans.

Future Prospects for East Coast Dyes and the Lacrosse Equipment Market

With a strong trademark foundation and innovative products like the MINT Lacrosse Ball, East Coast Dyes is well-positioned for continued growth in the lacrosse equipment market. The company’s evolution from a partnership to a corporation suggests plans for expansion and possibly diversification within the sporting goods industry.

What potential areas of growth exist for East Coast Dyes? Some possibilities include:

- Expansion into international markets

- Development of new lacrosse-related technologies

- Collaboration with other sports equipment manufacturers

- Increased focus on sustainable and eco-friendly product lines

As the lacrosse market continues to grow, particularly in North America, companies like East Coast Dyes that have established strong brand identities and innovative product lines are likely to see increased opportunities for market expansion and product development.

The Role of Innovation in Sustaining Market Position

East Coast Dyes’ success with the MINT Lacrosse Ball demonstrates the importance of innovation in maintaining a competitive edge in the sporting goods industry. By addressing specific player needs and improving upon existing equipment designs, ECD has carved out a unique position in the market.

How can East Coast Dyes continue to innovate in the lacrosse equipment space? Some potential avenues for innovation include:

- Incorporating advanced materials science into equipment design

- Utilizing data analytics to inform product development

- Exploring customization options for individual player preferences

- Developing smart equipment with integrated performance tracking capabilities

By continuing to focus on innovation and maintaining strong trademark protection, East Coast Dyes is well-positioned to capitalize on the growing interest in lacrosse and the increasing demand for high-performance sporting equipment.

The Importance of Brand Protection in a Competitive Market

East Coast Dyes’ trademark registration serves as a case study in the importance of brand protection for growing businesses in competitive industries. As the company continues to expand its product line and market presence, the legal protection afforded by their trademark registration will become increasingly valuable.

What challenges might East Coast Dyes face in protecting their brand as they grow? Some potential issues include:

- Counterfeit products entering the market

- Competitors attempting to create similar-sounding brand names

- The need for international trademark protection as the company expands globally

- Maintaining brand consistency across an expanding product line

By proactively addressing these challenges and continuing to invest in their brand identity, East Coast Dyes can strengthen their market position and build long-term value for their business.

The Impact of East Coast Dyes on Lacrosse Culture

Beyond their product innovations, East Coast Dyes has contributed to the broader lacrosse culture through their brand identity and community engagement. The company’s focus on performance and quality has resonated with players at all levels, from youth leagues to professional teams.

How has East Coast Dyes influenced lacrosse culture? Some notable impacts include:

- Raising expectations for equipment performance and durability

- Encouraging player creativity through customizable equipment options

- Sponsoring events and clinics to promote the sport

- Using social media to create a community of lacrosse enthusiasts

As East Coast Dyes continues to grow and innovate, their influence on lacrosse culture is likely to expand, potentially shaping the future direction of the sport and its equipment standards.

Lessons for Aspiring Sporting Goods Entrepreneurs

The success of East Coast Dyes offers valuable lessons for entrepreneurs looking to enter the sporting goods market:

- Identify and address specific pain points in existing equipment

- Prioritize quality and performance to build a loyal customer base

- Protect intellectual property early to secure brand identity

- Engage with the sports community to build brand awareness and trust

- Be prepared to evolve business structures as the company grows

By following these principles and maintaining a focus on innovation and quality, new entrants to the sporting goods market can hope to emulate the success of companies like East Coast Dyes.

The Future of Lacrosse Equipment Technology

As companies like East Coast Dyes continue to push the boundaries of lacrosse equipment design, the future of the sport looks increasingly high-tech. Potential developments in lacrosse equipment technology may include:

- Smart lacrosse sticks with integrated shot speed and accuracy sensors

- Advanced protective gear with impact-reactive materials

- Customizable equipment using 3D printing technology

- Environmentally sustainable manufacturing processes for all lacrosse gear

East Coast Dyes, with its established brand and history of innovation, is well-positioned to be at the forefront of these technological advancements in lacrosse equipment.

Conclusion: East Coast Dyes’ Lasting Impact on Lacrosse

From its origins as a small partnership to its current status as a registered corporation with a strong trademark, East Coast Dyes has made a significant impact on the lacrosse equipment industry. The company’s innovative products, particularly the MINT Lacrosse Ball, have set new standards for performance and quality in the sport.

As East Coast Dyes continues to grow and evolve, its influence on lacrosse culture and equipment technology is likely to expand. By maintaining its focus on innovation, quality, and strong brand identity, ECD is well-positioned to shape the future of lacrosse equipment and continue its success in the competitive sporting goods market.

The story of East Coast Dyes serves as an inspiring example for entrepreneurs in the sporting goods industry, demonstrating the potential for success through innovation, quality, and strategic brand protection. As the lacrosse market continues to grow, companies that can emulate ECD’s approach to product development and brand building are likely to find opportunities for success and lasting impact on the sport.

EAST COAST DYES Trademark of ECD LACROSSE, INC. – Registration Number 5523322

EAST COAST DYES – Trademark Details

Status: 700 – Registered

Serial Number

87703604

Registration Number

5523322

Word Mark

EAST COAST DYES

Status

700 – Registered

Status Date

2018-07-24

Filing Date

2017-11-30

Registration Number

5523322

Registration Date

2018-07-24

Mark Drawing

4000 – Standard character mark

Typeset

Published for Opposition Date

2018-05-08

Attorney Name

Joshua A. Glikin

Law Office Assigned Location Code

M50

Employee Name

VERHOSEK, WILLIAM T

Classification Information

International Class

028 – Games and playthings; gymnastic and sporting articles not included in other classes; decorations for Christmas trees. – Games and playthings; gymnastic and sporting articles not included in other classes; decorations for Christmas trees.

– Games and playthings; gymnastic and sporting articles not included in other classes; decorations for Christmas trees.

US Class Codes

022, 023, 038, 050

Class Status Code

6 – Active

Class Status Date

2017-12-12

Primary Code

028

First Use Anywhere Date

2012-05-01

First Use In Commerce Date

2012-05-01

Current Trademark Owners

Party Name

ECD LACROSSE, INC.

Party Type

31 – 1st New Owner Entered After Registration

Legal Entity Type

03 – Corporation

Address

Please log in with your Justia account to see this address.

Trademark Owner History

Party Name

ECD LACROSSE, INC.

Party Type

31 – 1st New Owner Entered After Registration

Legal Entity Type

03 – Corporation

Address

Please log in with your Justia account to see this address.

Party Name

East Coast Dyes

Party Type

30 – Original Registrant

Legal Entity Type

02 – Partnership

Address

Please log in with your Justia account to see this address.

Party Name

East Coast Dyes

Party Type

20 – Owner at Publication

Legal Entity Type

02 – Partnership

Address

Please log in with your Justia account to see this address.

Party Name

East Coast Dyes

Party Type

10 – Original Applicant

Legal Entity Type

02 – Partnership

Address

Please log in with your Justia account to see this address.

Correspondences

Name

JOSHUA A. GLIKIN

GLIKIN

Address

Please log in with your Justia account to see this address.

Prior Registrations

| Relationship Type | Reel Number |

| Prior Registration | 4430215 |

Trademark Events

| Event Date | Event Description |

| 2017-12-04 | NEW APPLICATION ENTERED IN TRAM |

| 2017-12-12 | NEW APPLICATION OFFICE SUPPLIED DATA ENTERED IN TRAM |

| 2018-03-13 | ASSIGNED TO EXAMINER |

| 2018-03-14 | NON-FINAL ACTION WRITTEN |

| 2018-03-14 | NON-FINAL ACTION E-MAILED |

| 2018-03-14 | NOTIFICATION OF NON-FINAL ACTION E-MAILED |

| 2018-03-14 | TEAS RESPONSE TO OFFICE ACTION RECEIVED |

| 2018-03-29 | ASSIGNED TO LIE |

| 2018-04-04 | CORRESPONDENCE RECEIVED IN LAW OFFICE |

| 2018-04-04 | TEAS/EMAIL CORRESPONDENCE ENTERED |

| 2018-04-05 | APPROVED FOR PUB – PRINCIPAL REGISTER |

| 2018-04-18 | NOTIFICATION OF NOTICE OF PUBLICATION E-MAILED |

| 2018-05-08 | PUBLISHED FOR OPPOSITION |

| 2018-05-08 | OFFICIAL GAZETTE PUBLICATION CONFIRMATION E-MAILED |

| 2018-07-24 | REGISTERED-PRINCIPAL REGISTER |

| 2020-10-28 | AUTOMATIC UPDATE OF ASSIGNMENT OF OWNERSHIP |

Dyes

Plants have been used for natural dyeing since before recorded history. The staining properties of plants were noted by humans and have been used to obtain and retain these colors from plants throughout history. Native plants and their resultant dyes have been used to enhance people’s lives through decoration of animal skins, fabrics, crafts, hair, and even their bodies.

The staining properties of plants were noted by humans and have been used to obtain and retain these colors from plants throughout history. Native plants and their resultant dyes have been used to enhance people’s lives through decoration of animal skins, fabrics, crafts, hair, and even their bodies.

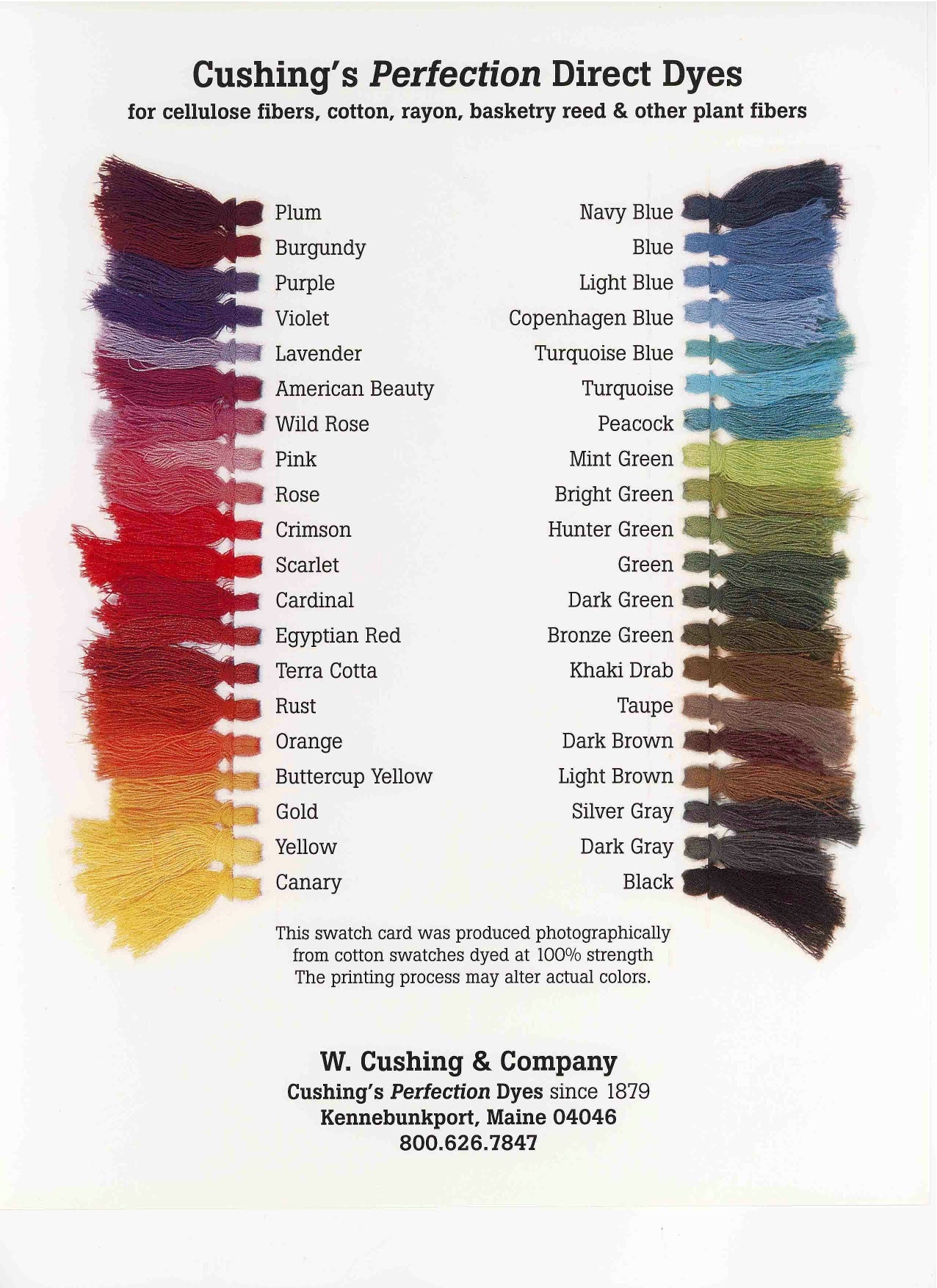

Types of Dyes

Natural dye materials that produce durable, strong colors and do not require the addition of other substances to obtain the desired outcome are called substantive or direct dyes. Sumac (Rhus spp.) and walnut (Juglans spp.) are native plant examples of direct dyes. Because these species are high in tannic acid, they do not require additional substances to be added for the dye to attach to fibers and form a durable bond. Dyes that need this type of assistance are called adjective or mordant dyes.

Mordants

Mordants are water-soluble chemicals, usually metallic salts, which create a bond between dye and fiber thus increasing the adherence of various dyes to the item being dyed. The actual color one gets from a natural dye depends not only on the source of the dye but also on the mordant, and the item being dyed.

The actual color one gets from a natural dye depends not only on the source of the dye but also on the mordant, and the item being dyed.

Most mordant recipes also call for the addition of cream of tartar or tartaric acid. Use of this readily available spice is important because it reduces fiber stiffness that can occur because of mordanting. It can also increase brightness.

| Mordant | Effect |

|---|---|

| Alum | Brightens the colors obtained from a dye source |

| Iron/Coppers | Darkens/saddens hues, produces blacks, brown, gray |

| Copper vitriol | Improves likelihood of obtaining a green hue |

| Tin | Produces bright colors especially yellows, oranges, reds |

| Chrome | Highly toxic – should not be used for dyeing at home |

Plants Used for Dyes

Throughout the world, evidence of natural dyeing in many ancient cultures has been discovered. Textile fragments dyed red from roots of an old world species of madder (Rubia tinctoria) have been found in Pakistan, dating around 2500 BC. Similar dyed fabrics were found in the tombs of Egypt.

Textile fragments dyed red from roots of an old world species of madder (Rubia tinctoria) have been found in Pakistan, dating around 2500 BC. Similar dyed fabrics were found in the tombs of Egypt.

Finely woven Hopi wicker plaques made from rabbitbrush and sumac stems colored with native and commercial dyes. Photo by Teresa Prendusi.

Mordants can be used to increase color intensity such as in this Southwestern–style rug. Photo by Teresa Prendusi.

- Tyrean purple dye was discovered in 1500 B.C. and was produced from the glandular secretions of a number of mollusk species.

- This purple dye was extremely expensive to produce as it required nearly 12,000 mollusks to produce 3.5 ounces of dye.

- Tyrean purple became the color of royalty.

- Lichens were used to produce ochril, a purple dye, which was called the “poor person’s purple”.

Native North American Plants Used for Dyes

European settlers in North America learned from Native Americans to use native plants to produce various colored dyes (see Table 2).:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9833863/East_coast_vs_West_coast_map.png)

| PLANT | Number of Uses |

|---|---|

| Mountain Alder | 53 |

| Red Alder | 21 |

| Bloodroot | 20 |

| Rubber rabbitbrush | 16 |

| Smooth sumac | 16 |

| Canaigre dock | 14 |

| Eastern cottonwood | 13 |

| Black walnut | 12 |

| Skunkbrush sumac | 11 |

| Butternut | 9 |

Bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis). Photo by Dave Moore.

Photo by Dave Moore.

Bloodroot (

Sanguinaria canadensis)

Bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis) was used to produce red dyes. Green dyes were made from algae and yellow dyes were made from lichens. Early colonists discovered that colors produced by the Native Americans quickly faded, thus suggesting that mordants may not have been used.

Mountain alder (Alnus incana).

Mountain alder (

Alnus incana)

This small, riparian tree has been used by many native tribes to make a brown, red-brown, or orange-red dye to darken hides, stain bark used in basketry and dye porcupine quills. Inner bark was used to make yellow dye. Outer bark was used to make a flaming red hair dye. Some tribes mixed this species with grindstone dust or black earth to make a black dye. Bark was used to wash and restore the brown color to old moccasins.

In the western United States, various layers of red alder bark, Alnus rubra, yield red, red-brown, brown, orange, and yellow dyes. These colors have been used to stain baskets, hides, moccasins, hair, quills, fishnets, canoes, cloth, and other items.

These colors have been used to stain baskets, hides, moccasins, hair, quills, fishnets, canoes, cloth, and other items.

Smooth sumac (Rhus glabra), an important dye plant, with fall colors.

Smooth sumac (

Rhus glabra)

This deciduous shrub is a widely distributed throughout most of the contiguous United States. It is readily recognized by its thicket-forming habit, milky sap, compound leaves, and dense, terminal panicles of bright red drupes. A variety of dye colors can be obtained from different parts of the plant depending on the mordant used.

The leaves are rich in tannin and can be used as a direct dye. Leaves can be collected as they fall in the autumn and used as a brown dye. The twigs and root are also rich in tannin. A black and a red dye can be obtained from the fruit. A black dye is obtained from the leaves, bark, and roots. An orange or yellow dye is obtained from the roots harvested in spring. A light yellow dye is obtained from the pulp of the stems.

Butternut (Juglans cinerea)

Butternut (

Juglans cinerea)

This tree native to the eastern United States was important as a food and dye source. Native Americans used the bark to make a brown dye and young roots to make a black dye. Using an iron mordant, brown dye can be changed to a charcoal or gray color.

- The famous gray coats that the Confederate Army wore during the Civil War were colored with dye made from butternuts.

- Confederate soldiers were called “butternuts” because of their dyed uniforms.

Rubus

The genus Rubus belongs to the rose family. Common names include raspberry, blackberry, blackcap, and thimbleberry. Varieties of blackberry include dewberry, boysenberry, and loganberry. This group consists of erect, arching or trailing, deciduous and evergreen shrubs found wild in Europe, North America, and Asia.

These berries are actually aggregate fruits, which means they are composed of individual drupelets, held together by almost invisible hairs. Some berry canes may be armed with formidable spines and make great security hedges, while others may be nearly spineless. All parts of the blackberry plant (berries, leaves, canes) yield dye colors.

Some berry canes may be armed with formidable spines and make great security hedges, while others may be nearly spineless. All parts of the blackberry plant (berries, leaves, canes) yield dye colors.

Rubus species are important for food, medicine, and dyes. Photo by Marry Ellen (Mel) Harte © Forestryimages.org.

| Dye Color | Plant Common Name (Additional Colors) |

|---|---|

| Yellow Dyes | Yarrow (green, black) |

| Honey Locust | |

| Golden wild-indigo (green) | |

| Tall cinquefoil (black, green, orange, red) | |

| Pecan (brown) | |

| Indiangrass (brown, green) | |

| Orange Dyes | Western comandra (brown, yellow) |

| Prairie Bluets (brown, yellow) | |

| Bloodroot (brown, yellow) | |

| Sassafras (black, green, purple, yellow) | |

| Eastern Cottonwood (black, brown, yellow) | |

| Plains Coreopsis (black, green, yellow, brown) | |

| Red Dyes | Ozark chinkapin (black, yellow, brown) |

| Sumac (yellow, green, brown, black) | |

| Chokecherry | |

| Prairie Parsley (yellow, brown) | |

| Slippery Elm (brown, green, yellow) | |

| Black Willow (black, green, orange, yellow) | |

| Purple / Blue Dyes | Indian blanket (black, green, yellow) |

| Hairy coneflower (brown, green, yellow, black) | |

| Red Mulberry (brown, yellow, green) | |

| Mountain alder (brown, red, orange) | |

| Summer Grape (orange, yellow, black) | |

| Black Locust (black, green, yellow, brown) | |

| Green Dyes | Butterfly milkweed (yellow) |

| Texas Paintbrush (green, red, yellow) | |

| Basket flower (yellow) | |

| Sagebrush (yellow, gray) | |

| Stinging nettle | |

| Goldenrod (yellow, brown) | |

| Gray Dyes | Iris (black) |

| Butternut (brown) | |

| Canaigre Dock (yellow, green, brown) | |

| Brown Dyes | Prickly poppy (green, orange, yellow) |

| Texas Paintbrush (green, red, yellow) | |

| Elderberry (yellow) | |

| Downy Phlox (brown, green, yellow) | |

| Black Dyes | Northern Catalpa (brown, yellow) |

| Sumac (yellow, red, green, brown) | |

| May-apple (brown, yellow) | |

| Sand Evening Primrose (green, orange, red, yellow) |

Did You Know?

- The tissues of canaigre dock (Rumex hymenosepalus) – a southwest desert native plant used to make yellow, gray or green dye, and widely noted for its medicinal, edible, and social uses – contain toxic oxalate.

The needlelike crystals produce pain and edema when touched by lips, tongue or skin.

The needlelike crystals produce pain and edema when touched by lips, tongue or skin. - Eastern cottonwood used to make a variety of dyes was a sign to early pioneers that they were near water. Ribbons of cottonwoods were found across the prairie where underground watercourses were located.

- Prior to chemical synthesis of indigo dye, blue jeans and cotton were dyed with a blue dye derived from tropical indigo bush, native to India. Mayo indigo, from the Sonoran desert was used for blue dye for thousands of years.

- Rubber rabbitbrush, a western native, can be used to create both green and yellow dyes. The bark produces green dye while flowers produce yellow dye.

- Not only is stinging nettle edible, it can be used to create a green dye. Stinging nettle can cause severe skin irritation, but is useful for dyes, fiber, and food.

For More Information

- Native American Ethnobotany Database – explore more about native plants used for natural dyes.

- Making Natural Dyes from Plants – examine some readily available natural plant dyes.

Canaigre dock (Rumex hymenosepalus). Photo by Teresa Prendusi.

Stinging nettle (Urtica dioica).

How moonshine is called in different parts of the world

How moonshine is called in different parts of the world

9 August 2018 11:52

Many are mistakenly convinced that only residents of the former Soviet republics can engage in the manufacture of moonshine. In fact, this is a delusion and in many countries there is a moonshine that has its own roots, name and history. All these drinks have their own unique aromatic, taste, color qualities, because in each country they are made from their own local raw materials and according to their own recipes. But what do they have in common – they are all prepared in ordinary home conditions from improvised tools using similar methods.

And, of course, in every country moonshine is called in its own way. We will tell you about the most common of them. You could even try some of these drinks before, without even suspecting that this is actually a kind of moonshine. And other names will seem funny to you.

We will tell you about the most common of them. You could even try some of these drinks before, without even suspecting that this is actually a kind of moonshine. And other names will seem funny to you.

Moonshine (USA) – derived from “moonraker” (colloquial name for smugglers from the east coast of England). The word “moonshine” appeared later, in the 19th century in the North American Appalachian region. Where emigrants from Ireland and Scotland secretly from the authorities at night were distilling moonshine and distributing it further.

Slivovitz (Czech Republic) – Residents throughout the Czech Republic prepare slivovitz (or plum brandy) at home, moreover, residents of the eastern part of the country cook with a vengeance.

Lotoko (Democratic Republic of the Congo) is a cassava whiskey. Due to the official ban by the authorities, its producers are flourishing. The ban creates demand, but the main thing is that this drink is much stronger and cheaper than alcohol in stores. And the majority of the population of the Congo has a fairly modest income.

And the majority of the population of the Congo has a fairly modest income.

Schwarzgebrannter (Germany) – Agree, the name is unusual for its beauty, and the meaning is simple – “moonshine”. The allowed sales volume is no more than half a liter, although the Germans themselves are not very interested in this drink, preferring only high quality alcohol.

Witblits (South Africa) – translated as “white lightning”. Strong unaged grape brandy. The city of Philippolis holds an annual festival in honor of this drink, including drinking competitions for the titles of Mr. and Mrs. Witblits.

Peatreek (Scotland) – illegally produced whiskey. The word refers to the smell emanating from the fire on which this drink is distilled.

रक्शी (“rakshi”, Nepal) is a Nepalese and Tibetan grain-based alcoholic beverage. At home, it is most often made from rice or millet.

Absinthe (Switzerland) – yes, absinthe has been an illegal drink throughout its history. Only in 2005 did the Swiss authorities recognize it and allow official production.

ჭაჭა (chacha, Georgia) is a strong alcoholic drink belonging to the class of grape brandy from berry pressing. An analogue of chacha is the Italian grappa.

Grappa (Italy) – an alcoholic drink with a strength of 36-55 degrees. It was originally produced for the environmentally friendly disposal of production waste at the end of the wine season. But grappa quickly became an illegal way to relax, and soon it was completely put into mass production in order to protect the population from poisoning with a low-quality product.

Samagonka, garelka (Belarus) – the law in the country prohibits private individuals from making any alcoholic beverages. But, this is not a hindrance to offer a “glass or two” in every village.

Horilka (Ukraine) – a strong alcoholic drink made from purified alcohol, there are many traditional moonshine tinctures. The most popular are: pepper, mead, kalganovka, chasnikovka, bison, dzhendzhora, kminivka.

In each country, moonshine has its own name and meaning for its inhabitants, consists of a variety of ingredients, and is made according to unusual recipes. And this is wonderful, because diversity is always a source of new experiences.

Tags:

- interesting

Turkmens (Peoples and cultures) – 2016

domestically produced semi-silk fabric (Pirkulieva, 1973.

p. 26).

Turkmenistan is the birthplace of the silk house weaving fabric keteni. In the regions of ancient Merv, Dzhurjan and Dakhistan, sericulture was known until the 6th century BC and was developed mainly among settled tribes: murchali, nokhurli, alili, geoklen, etc. (Bogolyubov, 1908. P. 5; Mikhailov, 1900. P. 74; Masson, 1946. P. 175). Sericulture, silk weaving and chintz dressing were well developed among the geoclans of Sumbara and Chandyra. ohm (Bode , 1847. S. 214,215).

P. 175). Sericulture, silk weaving and chintz dressing were well developed among the geoclans of Sumbara and Chandyra. ohm (Bode , 1847. S. 214,215).

In addition, geocloths produced colored silk, woolen and cotton fabrics for sale. The famous orientalist K.K. Bode reported: “The Gueuclin silk and woolen manufactory proves its industrial ability. The matter they make combines the strength of the fabric with the brilliance of colors and the beauty of the pattern. There are no machines, everything depends on the art of the hands of hardworking Turkmen women, who, despite all the daily chores, still manage to weave these beautiful fabrics, highly valued even by European trade”

(Bode, 1865, p. 13).

“Göklens … grow mulberry plantations, and women weave silk fabrics”, which were in great demand among neighboring groups (yomud), as well as in the border villages of Iran. Mudarya with a width of 5-10 km there are plantations of mulberry” ( Galkin, 1867.

P. 45; Ovezov, 1976. P. 97; Pirkulieva, 1973. S. 12).

P. 97; Pirkulieva, 1973. S. 12).

In almost all hauls of the Middle Amu Darya, Turkmen women have been producing a variety of silk fabrics for a long time. Only in one Kerkinsky bekstvo

at the beginning of the 20th century about 15 thousand boxes of grain were fed annually (TsGATSSR. F. 616. Op. 1. D. 2. L. 269–279). The northern regions of the Middle Amu Darya valley also produced silk fabric with stripes. In the villages of Palvart and Halach

in large quantities weave white silk and semi-silk cloth, multi-colored silk scarves, a significant part of which was exported to Iran and Afghanistan –

camp (Pirkulieva, 1973. p. 25).

In the regions of Akhal, Atek, and the Middle Amudarya, sericulture played a significant role in raising the budget of the economy. The Turkmens created perfect methods of silkworm breeding. They successfully engaged in sericulture and produced self-woven fabrics from silk and cotton. Chovdury and yomudy were mainly engaged in the production of woolen fabrics. In addition to fabrics made of camel and brown sheep wool, both men’s and women’s guşak sashes and woolen footcloths ýüň dolak were used for rawhide boots and shoes. At the beginning of the twentieth century. the production of woolen fabric for cäkmen dressing gowns reached 10 thousand pieces a year (Vasilieva, 1969, p. 58; TsGAOR TSSR.

In addition to fabrics made of camel and brown sheep wool, both men’s and women’s guşak sashes and woolen footcloths ýüň dolak were used for rawhide boots and shoes. At the beginning of the twentieth century. the production of woolen fabric for cäkmen dressing gowns reached 10 thousand pieces a year (Vasilieva, 1969, p. 58; TsGAOR TSSR.

F. 1. Op. 4. D. 66. L. 143).

200

Twisting threads inside the yurt

Postcard from the beginning of the 20th century.

The process of initial processing of silk from unwinding cocoons to dyeing is almost the same for all ethnic groups of Turkmens. According to the statistics, as far back as the beginning of the 20th century, the Durunsky office (which included the village of Murche) provided about half of all cocoons in the Transcaspian region (Ivanov, 1900.S.4; Petrovsky, 1894.S.117). .The initial processing of silk consisted of preliminary cleaning of silk threads on two machines, and then rewinding their coils onto spools. The silk was then twisted and made threads suitable for weaving.

The silk was then twisted and made threads suitable for weaving.

For yarn dyeing, Turkmens almost until the end of the 19th century. used vegetable dyes. Aniline dyes became widely used later. The yarn was dyed mainly in red, yellow, green

and blue colors. One of the important features of the material is their color, which is determined by the color of the dyes.

Throughout Turkmenistan, preference was given to red. According to popular beliefs, the red color had magical properties, protected from the actions of evil forces. In addition, the Turkmens have long identified red with the beautiful, cheerful.71.S.186). Red color

and today is especially popular among girls and young women.

201

As a result of dyeing, fabrics acquired one or another color of sufficient strength, the color range of Turkmen clothing did not require the use of numerous and varied dyes. Several terms are used for various shades of red in the Turkmen language: kermez, kirmiz, karmezin, gyrmyzy.

Dyes were obtained from special dye plants. So, for example, scarlet – from the root of the ýerboýasyn plant, yellow paint was made from the saryçöp plant or from mulberry leaves. Cultivated for a long time in a temperate climate and wildly growing at the foot of the Kopetdag, madder (Rubia tinctorum) was very common, giving a good harvest on saline lands where other plants did not take root. Dimensions of madder plantations in the middle of the XIX century. were so great that it went not only for local needs, but also for export. They also used imported grainy red paint (gyrmyzy boýag). Indigo (göknil) was of great use in the art of dyeing, both for dyeing silk in all shades of blue and green.

For dyeing and for better fixing of mordants on silk fiber, zyak alum, mined locally in the mountains, was used, for bleaching fabrics – potash. As a bleaching agent, ash from coal was used, the fabric acquired an unusual whiteness. Starch was also used, which was made as follows: water with wheat flour added to it was brought to a boil, matter was lowered into the mass, and then the product was dried and leveled.

Loom. In the 19th – early 20th century. for home weaving, all types of woven fabrics were made on a tara or ducan loom of a simple device. The Turkmen loom differs little from the loom of the neighboring peoples of Central Asia (Peoples of Central Asia and Kazakhstan. 1962, pp. 453, 576;

Rusyaikina, 1959, p. 150; Bobrinsky, 1908).

Akhal home loom (Ashgabat, the village of Sinekli both, Kyoshi, Sunche and Murche both, Nokhur both, Archman, Bakharden), as the predominant type, was distributed in other regions of Turkmenistan: in separate areas of Atek, among the Saryks and Tekins of Murgab, among the ethnic groups of the Karabekaul region , settlements Khalach, Kizyl-Ayak, Khodjambas (FMA, 1989, 1999, 2007, 2013).

Centuries-old traditions and skills that have survived to this day in a simple weaving technique remain unchanged. In Ashgabat to this day there is an old horizontal machine (length – 2 or 2.5 m, width – 80–90 cm). The main parts of the loom are three separate gazyk wooden supports – 30–40 cm high stands, arranged as if at the corners of a triangle at a distance of 70–80 cm from one another, which depends on the width of the future fabric. A rounded iron beam (nowert) is installed on the gazyk – a wooden spool, a roller (diameter 7–8 cm) with a smooth surface on which threads are wound – there is a hole on the right for fixing when winding the finished fabric (Bayrieva, 1986.

A rounded iron beam (nowert) is installed on the gazyk – a wooden spool, a roller (diameter 7–8 cm) with a smooth surface on which threads are wound – there is a hole on the right for fixing when winding the finished fabric (Bayrieva, 1986.

C .17).

After dyeing the threads, the Turkmen women were engaged in the preparation of the warp for weaving, which includes the warp operation. It consists in selecting the warp threads according to the pattern of the fabric: i.e. each thread in a certain sequence is threaded through the shafts (the working body of the loom,

202

, which lifts and lowers the warp threads), and then through the reed mouse (kind of comb). With the help of a needle, the weaver passes the warp on the other side of the comb, two threads together. The missed threads are divided into parts, tied in a knot and sewn to a canvas rag wound on a navoi. The stretched part of the base is straightened and stretched along the entire length of the horizontal machine.

Yarn (eriş) is stretched parallel to one of the sides – the basis for the future fabric. An iron rod or an axis with a curved end (gulakҫow) is inserted into the right end of the beam, with the help of which the weaver (taraçy) turns the beam to wind the finished fabric and hold the warp in the desired tension. To balance the edges of the fabric, a wooden plank with iron teeth along the edges (indemir) is used. The weaver sits in front of the beam on a tahta board, her legs dangling into a shallow hole dug under the loom, her legs rest against the loops of the harness (güle), specially made for the legs, descending from the ceiling on double woolen ropes (güle ýüpi) (Bayrieva, 1987.

p. 27).

The second option is a portable tare machine, which is installed in city apartments in one of the rooms near the window. It differs only in the absence of a footwell, in view of the fact that the third rack is much higher than the two front ones. The entire base narrows towards the end of the loom, passing through a darty crossbar inserted into the third support (on gazyk). Further, in the form of a long beam, it is attached high to the ceiling and moves to the beam as the weaving process progresses. This machine can be easily moved and transferred from one room to another in an unassembled form, which allows you to do weaving all year round (Bayrieva,

Further, in the form of a long beam, it is attached high to the ceiling and moves to the beam as the weaving process progresses. This machine can be easily moved and transferred from one room to another in an unassembled form, which allows you to do weaving all year round (Bayrieva,

1987, p. 28).

A good weaver can weave up to 8 m of fabric 35 cm wide per day. Such a cut (bir köýneklik or sekiz gaty) was enough for a dress, and part of a particularly expensive fabric from the back was used for the lower embroidered part of women’s trousers (balak ýüzi) or men’s skullcaps tahýa (Ahal. PMA, 1 989).

At the end of the prepared portion of yarn, the weaver extends the threads. This type of work, ulamak, consists in connecting and gluing the ends of the threads. The craftswoman takes opposite flagella one by one, straightens and connects their ends, dipping her fingers into the glue from şepbik apricots, then twists them with her palms.

When a certain amount of material is accumulated on the loom (8–10 m for one dress or bathrobe), the fabric is cut with scissors, placed in a roll or wound on a pile. At the same time, a strip of finished matter remains on the machine, to which the base is then attached for the next refueling of the machine.

At the same time, a strip of finished matter remains on the machine, to which the base is then attached for the next refueling of the machine.

Various rituals and beliefs were associated with weaving in the past. Even today, Turkmen women revere the patroness of weavers, Bibi Patma, in the form of a kind old woman with high skills. In Afghanistan, she is called Bibi Charhan (Mistress of the Distaff) (Andreev, 1957. S. 69, 70). Craftsmen carefully preserve and creatively develop the local traditions of weaving

to this day.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the Turkmen economy was of a semi-natural nature, providing the necessary materials for the manufacture of a full range of clothing: cotton, wool, silk, leather and sheepskin. The quality of the materials was quite different –

203

Likewise, each kind of fabric was intended for a certain type of clothing. Balkhan yomudki, nokhurki, shikhi of Akhal, murche and sunche, ali eli, salyr Serakhsa sewed dresses from homespun silk (keteni, serendi, gyrmyzy) and cotton fabrics (nah mata, alaçin, alatow) from various colors of silk fabrics (ahal keteni, sary ýüpek mata). Women from wealthy families sewed rich and elegant dresses from smooth silk fabric daraýy, gyrmyzy keteni of dense workmanship.

Women from wealthy families sewed rich and elegant dresses from smooth silk fabric daraýy, gyrmyzy keteni of dense workmanship.

Murcha silk was considered one of the best among the Turkmens, for which they specially came from other regions and from the capital Ashgabat. Therefore, a good half of the murchali silk products went on sale, mainly gyrmyzy köýneklik silk for women’s dresses, gyrmyzy donlyk for men’s dressing gowns, gyrmyzy çabytlyk for women’s bedspreads. Among the Murchintsy, sericulture was a purely female craft, in contrast to the Shikhs living in Bakharden (now Bakharly), where men were engaged in this along with women (Ovezov, 1959.

pp. 159, 175).

Homespun and factory fabrics were also imported. Particularly common were alaça and alatow, bought in Iran, gyrmyzy – silk homespun fabric from Ahal, chintz, calico, taffeta and cloth of various varieties, brought from Russia and other European countries, as well as Indian silk shawls that served as capes for women.

There were traditional centers for the production of certain types of fabrics. It was used for sewing elegant women’s dresses. Onbirüille (thick silk fabric), red-yellow striped silk fabrics çepbet or red-white gyzyl alat were used for sewing robes. Semi-silk alaça, sowsany were more often used by the elderly. The basis of sowsany was made of red silk, and the wefts were made of blue paper threads, which is why the fabric, shimmering when moving, was called gije-gündiz (night-day). Everyday dresses of the Turkmen women were sewn from red one-color satin elwar and cotton fabric mata (saryk, geoclen) or home-made semi-silk fabric alaça (among teke and salyrs). At the end of the XIX century. A large place in the manufacture of clothing began to be occupied by imported factory fabrics – chintz, satin, silk of red tones with a floral pattern.

The favorite shades for fabrics and carpets in the Parthian time and the Useljuks were warm tones – purple, red, yellow, violet (Pugachenkova, 1982, p. 265). Even men of any age (except for the elderly) of the Murche, Nokhur, Alili tribes wore silk red shirts gyrmyzy köýnek and red pants gyrmyzy balak until the middle of the 20th century.59.S.216).

265). Even men of any age (except for the elderly) of the Murche, Nokhur, Alili tribes wore silk red shirts gyrmyzy köýnek and red pants gyrmyzy balak until the middle of the 20th century.59.S.216).

There was some age difference in the color of the fabric for dresses and belts. Girls and young women of Nebit-Daga and Kum-Daga preferred to wear red and green clothes, while older women liked brown (Annaklychev, 1961, p. 91). From the yellow silk fabric çepbet in a narrow strip of orange and red-brown color, women’s outerwear and dressing gowns were sewn. Thick and plain silk –

204

yellow and dark green forged fabric for head capesçyrpy, kürte. After the advent of chemical dyes, the Turkmen women could not extract the natural green color, a noble dark olive shade. Instead, a black fabric was obtained, which was used for kürte capes, but the former name ýaşylkürte (green cape) remained in the people. 1994.

p.57).

Turkmen women and men wore festive, wedding dresses, shirts and handicraft silk and semi-silk trousers – gyrmyzy and ýaşyl keteni. Silk and cotton fabrics of Teke and Saryk production were very popular. Uzbek fabrics were in great use among the northern Yomuds and Amu Darya ersaris. Cotton striped dark red and dark green fabrics of Khiva production were used for wadded men’s dressing gowns, shahy silk – for women’s festive clothes, çit – for the lining of clothes, especially women’s dressing gowns in large quantities. Yomuds of the eastern coast of the Caspian Sea sewed clothes from silk and woolen fabrics of Iranian production (Muraviev, 1822. P. 35; Karelin, 1836.

Silk and cotton fabrics of Teke and Saryk production were very popular. Uzbek fabrics were in great use among the northern Yomuds and Amu Darya ersaris. Cotton striped dark red and dark green fabrics of Khiva production were used for wadded men’s dressing gowns, shahy silk – for women’s festive clothes, çit – for the lining of clothes, especially women’s dressing gowns in large quantities. Yomuds of the eastern coast of the Caspian Sea sewed clothes from silk and woolen fabrics of Iranian production (Muraviev, 1822. P. 35; Karelin, 1836.

S.286,287; Ogorodnikov, 1878. S.213,214).

Among the Turkmen, simple and strong white calico was in great demand – cotton fabric (40–45 cm wide) with a linen weave – and semi-silk fabric in small cells alaça (blue-red or pink-violet). The name comes from the word ala (variegated). In Russia, she was known under the name motley (Bayrieva, 1994, p. 79). She wore women’s dresses and men’s shirts. Nah mata fabric, predominantly white in color, was mainly used for men’s and women’s underwear.

For everyday wear, it was dyed blue for dresses for girls and dark blue for women. Blankets were quilted from such coarse calico, tablecloths were made. Yomuds wore the widest trousers made of coarse calico, quilted on wadding. Bags were made from calico, it was used as a bandage. Dresses dyed red, satin elwan, sowsany were preferred by older women. These fabrics were produced from high-quality thin even yarn of various colors.

In the past, Turkmen women daily wore dresses made of chintz – jir mata, and printed chintz – gülli jir was used as a lining for dressing gowns. Outerwear for the old people (shirts and pants), head scarves gyňaç for old women, and shrouds kepen were sewn from white material. A scarf made of white material is worn by the bride in a. Murche, and she wears it for a day before putting on the female headdress baş daňmak (Ovezov, 1959, p. 218; Vasilyeva, 1954, p. 151).

Woolen fabrics were mostly produced in pastoral areas where sheep and camel breeding were significantly developed. A thick fabric of sheep’s wool, dyed in blue-blue and gray colors, was used by the saryks as outerwear for men, white and blue – for men’s shirts, and black – for men’s upper trousers. In addition to single-color woolen fabrics, narrow brown fabrics were popular throughout Turkmenistan.0005

A thick fabric of sheep’s wool, dyed in blue-blue and gray colors, was used by the saryks as outerwear for men, white and blue – for men’s shirts, and black – for men’s upper trousers. In addition to single-color woolen fabrics, narrow brown fabrics were popular throughout Turkmenistan.0005

205

fabric with black or dark blue stripes (1.5–2 cm) used for sewing saçak tablecloths in which bread was stored (Pirkulieva 1973.

p. 26).

The wool of young camels (1-2 years old) was used to make an excellent fabric for dressing gowns. One woman per year could make one piece of about 9 arshins in length from 14 to 15 inches in width. The fabric produced by the Salyrams and Saryks was highly valued in Persia and Herat. Representatives of the same tribe produced cheaper white lambswool fabric (Lessar, 1885, p. 53).

In 1869, the first dye was synthesized, capable of dyeing fabrics no worse than natural. It was called in consonance with “alizari” – alizarin. This was followed by the birth of other artificial dyes, not inferior to natural ones in their brightness, richness and depth of color. By the beginning of the twentieth century. synthetic or chemical dyes have practically replaced natural dyes from the costume world.

By the beginning of the twentieth century. synthetic or chemical dyes have practically replaced natural dyes from the costume world.

Natural fabrics were easily dyed blue with the sap of a very common indigo plant (Indigofera tinctoria): the Turkmens imported the “royal” blue dye indigo nil from Iran and India. Rare and precious paint gives a deep bright color when stained. Even fragments of fabric found during archaeological excavations, dyed with indigo a century and a half ago, retain its brightness and as if they were dyed only yesterday.

Rhubarb root, as well as pomegranate peels, onion skins, and tea were used as a yellow dye. In Merv, Takhtabazar, Bakharden, finely crushed madder core was used to dye yarn yellow.

In the past, after special processing, starched and polished to a gloss, keteni gave the impression of a divine fabric, radiating

brilliance and richness. Even the smell and the rustle of this magical fabric fascinated people. An indescribable thrill emanated from her, making a charming impression. “In the bazaar, the Oriental, who only here reveals himself in all his originality, loves çahçuh, i.e. rustle of clothes, and I’m

“In the bazaar, the Oriental, who only here reveals himself in all his originality, loves çahçuh, i.e. rustle of clothes, and I’m

it was a great pleasure to watch the buyer in the new çapan pace back and forth to test the power of the sound” (Vambury, 1865.

p. 67).

I would especially like to note the unsurpassed qualities of modern keteni, spun from silkworm, which Turkmen women from ancient times dyed by hand. Currently, keteni is produced from natural and rayon silk at textile factories and combines in Ashgabat, and it is widely used not only throughout the country, but also abroad.

Turkmen weavers continue to search for new forms and means of artistic expression, carefully preserving everything beautiful that was created by the people over the centuries. They introduce into production dozens of new types of silk fabric in combination with cotton, wool and synthetic fibers, woven products with ornamental motifs, restore old stylization and develop new techniques.

206

Today, Turkmenistan has confidently secured the status of a country – a major producer of textile products, which is in high demand on world markets. A kind of showcase of the country’s achievements, its “visiting card” in this area have become two new shopping centers in the capital of the country, Ashgabat – “Ak pamyk” and the House of Models. Exhibition collections are created, the original traditions of the Turkmen costume are preserved and popularized as an integral part of the national culture.

TURKMEN’S NIGHTMARE

Hundreds if not thousands of essays, articles and books have been written about carpets in general and Turkmen carpets in particular. They are sung by poets in their poems, filmmakers make bright films about them, they appear in any advertising publication. This, of course, is due to the fact that the carpet looks brighter, more elegant, richer and requires much more time for its much more complex and labor-intensive production. Nevertheless, it was the felt in the life of nomadic and semi-nomadic peoples, even after their transition to a settled way of life, that played

and plays a much larger role than the carpet. This fully applies

This fully applies

ik to the Turkmens.

Nightmare (keçe) in the everyday life of Turkmens, as well as a number of other peoples, was multifunctional. The wagons or yurts (gara öý) of ordinary Turkmens were covered with dark felt, and the yurts of people of noble, important guests or newlyweds (ak öý) were covered with white. In case of bad weather, the chimney opening in the yurt was closed with a special koshomka (serpik). Nightclubs, except for the richest, usually covered the floor inside the yurt. They were also spread out in the warm season outside the premises, on the ground for relaxation, tea drinking, conversations with guests or the production of certain works. From felt felt blankets were made for horses and hounds (tazy) especially dear to the heart of the Turkmen, capes for shepherds (ýapynja), often hanging cradles (sallançak) and various small household items, up to large triangular doga amulets that are hung over the entrance to the house. Babies used to come into this world on a felt mat, and on it the gray-bearded elders left it. Finally, special white koshoms are used as namazlyk prayer rugs, on which believers offer prayers to Allah.

Finally, special white koshoms are used as namazlyk prayer rugs, on which believers offer prayers to Allah.

Felt mats, thanks to the sheep wool from which they are made, have not only a thermal effect. With their thick, hard hairs, they significantly prevent such dangerous representatives of the local fauna as karakurts, phalanxes, scorpions from creeping up to the person who is on them. , this takes on special significance. Moreover, there is an opinion that nightmares, especially those that made from the wool of lambs, are very beneficial for human health.

In light of the above, it is not surprising that in the riddle associated with the felt, it is given such a flattering characterization. Let’s pay attention that in the text on –

207

Breakdown of wool. Akhal. 1980s

Photo from the archive of SM Demidov

The main features of felt mats are called: strength, water resistance and elasticity.

Aýy ýetse egilmez, Suwy ýetse, süýülmez, Gundagda daşa degen,

Daşa ursaň, döwülmez.

A bear will step on it – it will not bend, Water will climb – it will not stretch out, In a diaper wrapped up You will hit a stone – it will not break

(Dana Szler. 1978. P. 113.

Translated by the author)

and the desired softness and texture. This process, although considered the simplest, requires a lot of time and effort. Wool breakdown can be done by both adult women and girls.

After breaking down the wool, on a clean, flat area, the women spread out a large reed mat (which appears in the riddle of the felt mat as a kind of diaper). The wool of the base, usually dark in color (black or dark gray), is applied to it, the edges of which create a decorative canvas for the entire felt. Then most of the dark surface is covered with white wool. These manipulations are already carried out only by experienced felt felters.

The third stage in the manufacture of felt mats not intended to cover the yurt, i.e. monochromatic, mostly dark (which is why the Turkmen nomadic dwelling received the commonly used name gara öý, “black

208

Laying the wool for the base of the felt mat. Ahal. 1980s

Ahal. 1980s

Photo from the archive of S.M. Demidov

yurt”) , was laying out and rolling this or that pattern into the base, which, of course, required special skill. The very technology of rolling howling – lok, more precisely, multi-colored wool, into another, as one of the authors who wrote about Turkmen felt mats, “does not differ from that known among the Kazakhs and Kirghiz. Soft, rounded lines, almost merging with the background, spread the pattern of Turkmen felt” (Rafaenko, 1988. S. 143). Then the felt felters roll the laid out pattern into the base of the felt, mainly by tamping the wool with the palms, their base and rib, and, where possible, with the lower part of the arms up to the elbow joint and with the elbows themselves. Then, the raw felt laid out on the mat by women sitting in a row is tightly and neatly rolled up together with the mat placed under it, and after that two strong men, one on each side (sometimes replaced by two women each), begin to roll the rolled roll, pulling it alternately towards you by special ropes attached to the mat.

The needlelike crystals produce pain and edema when touched by lips, tongue or skin.

The needlelike crystals produce pain and edema when touched by lips, tongue or skin.