Who is David Shew and what are his contributions to plant pathology. How does his research impact disease management strategies. What are the key focus areas of his lab’s investigations. How does David Shew’s teaching contribute to educating future plant pathologists.

David Shew’s Expertise in Entomology and Plant Pathology

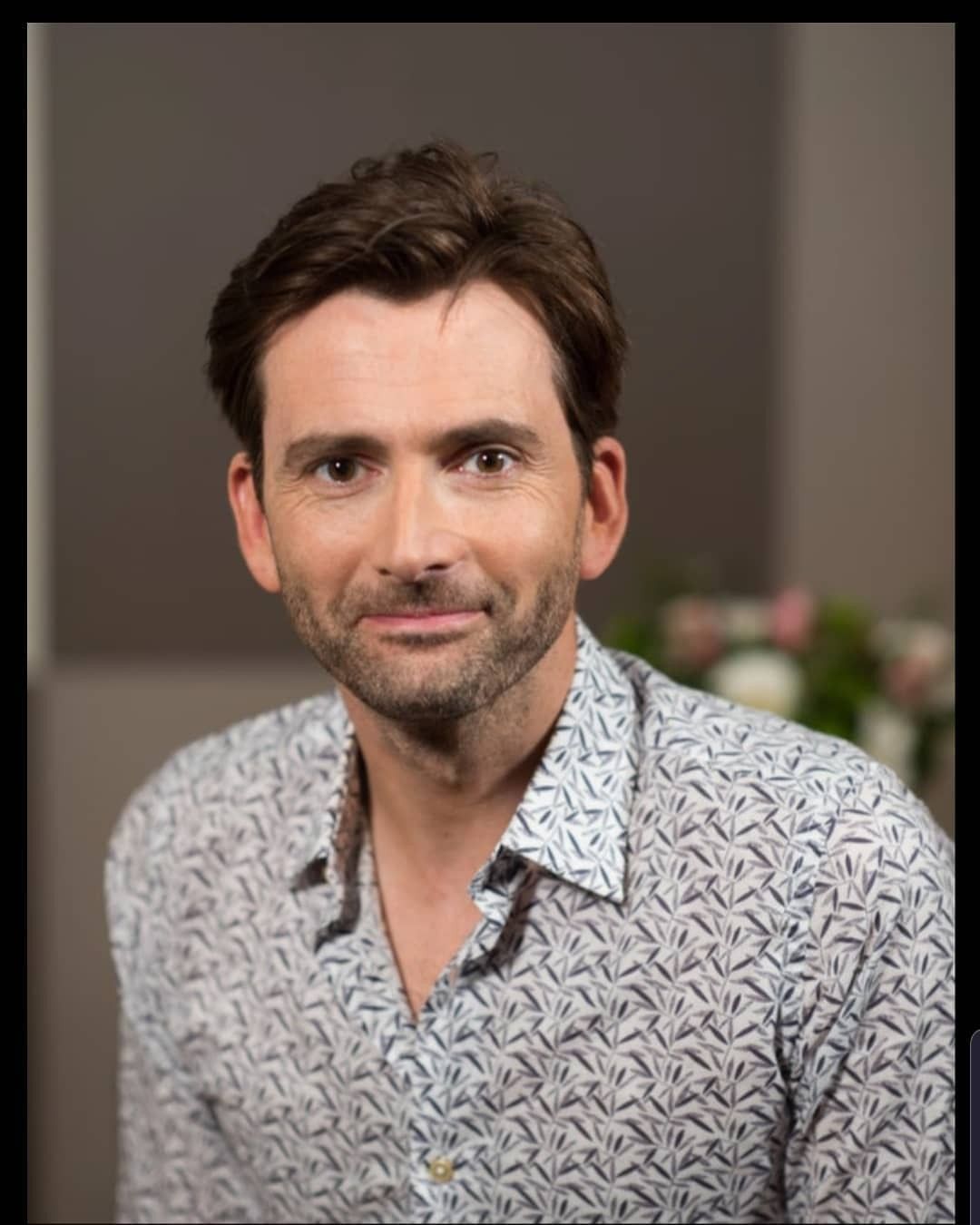

David Shew is a prominent figure in the field of Entomology and Plant Pathology, known for his extensive research on soilborne fungal pathogens. His work has significantly contributed to our understanding of plant diseases and their management strategies. Shew’s lab at North Carolina State University focuses on the ecology and epidemiology of these pathogens, aiming to develop more effective short-term and long-term disease management approaches.

Key Research Areas

- Effects of soil properties on fungal populations and disease suppression

- Host resistance mechanisms to root pathogens

- Characterization of pathogen populations in natural and agricultural ecosystems

Shew’s research has practical implications for agriculture and plant health management. By studying the intricate relationships between pathogens, plants, and their environment, his work contributes to developing more sustainable and effective disease control strategies.

Innovative Approaches to Understanding Soilborne Pathogens

Shew’s lab employs a multifaceted approach to studying soilborne fungal pathogens. Their research methodology involves:

- Analyzing soil physical and chemical properties

- Investigating host-pathogen interactions

- Comparing pathogen populations across different ecosystems

This comprehensive approach allows for a deeper understanding of the complex dynamics involved in plant disease development and progression. Can soil properties influence disease suppression? Research from Shew’s lab suggests that certain soil characteristics can indeed play a role in naturally suppressing plant diseases, opening up new avenues for sustainable disease management strategies.

Contributions to Tobacco Disease Research

One of the significant areas of Shew’s research has been the study of diseases affecting tobacco plants. His work on Phytophthora nicotianae, the causal agent of black shank disease in tobacco, has been particularly noteworthy. Shew and his colleagues have investigated various aspects of this pathogen, including:

- Resistance mechanisms in tobacco breeding lines

- Characterization of new Phytophthora species

- Assessment of genetic diversity in field populations

These studies have provided valuable insights into the nature of tobacco diseases and potential strategies for their control. Is genetic diversity in pathogen populations a concern for disease management? Shew’s research indicates that changing race structures in pathogen populations can indeed pose challenges for developing durable resistance in crop plants.

Exploring the Impact of Climate Change on Plant-Pathogen Interactions

David Shew’s research extends beyond traditional plant pathology to explore the potential impacts of climate change on plant diseases. His collaborative work has investigated how elevated CO2 levels affect soil microbial responses and organic carbon decomposition. These studies provide crucial insights into how future climate scenarios might influence plant-pathogen interactions and ecosystem dynamics.

Do elevated CO2 levels affect plant disease dynamics? Research involving Shew has shown that arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi can increase organic carbon decomposition under elevated CO2 conditions, highlighting the complex interactions between climate change, soil microbes, and plant health.

Advancing Turfgrass Pathology

While much of Shew’s work focuses on agricultural crops, he has also made significant contributions to turfgrass pathology. His research has addressed various diseases affecting turfgrass, including:

- Gray leaf spot caused by Pyricularia grisea

- Pythium root dysfunction

- Brown patch disease

These studies have practical implications for golf course management and the turfgrass industry. How does irrigation frequency affect turfgrass diseases? Shew’s research has shown that factors such as irrigation frequency, organic matter content, and grass cultivar can significantly impact the development of diseases like Pythium root dysfunction.

Innovative Approaches to Plant Disease Resistance

David Shew’s work extends into the realm of biotechnology and genetic engineering for plant disease resistance. Collaborating with other researchers, he has explored innovative approaches to enhancing plant resistance to various pathogens. Some notable examples include:

- Expression of bacteriophage T4 lysozyme gene in tall fescue for resistance to gray leaf spot and brown patch diseases

- Evaluation of tobacco germplasm for seedling resistance to stem rot and target spot

These studies demonstrate the potential of genetic engineering in developing disease-resistant crop varieties. Can genetic modification provide a sustainable solution to plant diseases? While Shew’s research shows promising results, it also highlights the need for continued research to fully understand the long-term implications and effectiveness of these approaches.

David Shew’s Role in Education and Mentorship

Beyond his research contributions, David Shew plays a crucial role in educating the next generation of plant pathologists. He teaches an undergraduate course, PP 315: Principles of Plant Pathology, which provides students with a comprehensive overview of plant pathogens, disease development, and management strategies. The course is offered both on-campus and as a distance education option, making it accessible to a diverse range of students.

What makes Shew’s teaching approach unique? His course combines theoretical knowledge with hands-on experience, allowing students to work directly with organisms that cause plant diseases. This practical approach helps students develop a deeper understanding of plant pathology concepts and their real-world applications.

Course Highlights

- Overview of plant pathogens and disease processes

- Hands-on experience with disease-causing organisms

- Opportunities for honors work for undergraduate students

- Diverse student body ranging from sophomores to graduate students

Shew’s commitment to education extends beyond the classroom. His lab provides opportunities for students and researchers to engage in cutting-edge plant pathology research, fostering the development of future scientists in the field.

Collaborative Research and Interdisciplinary Approach

One of the hallmarks of David Shew’s work is his collaborative approach to research. His publications demonstrate extensive cooperation with colleagues from various disciplines, including:

- Soil scientists

- Plant breeders

- Molecular biologists

- Agronomists

This interdisciplinary approach allows for a more comprehensive understanding of plant diseases and their management. How does collaboration enhance plant pathology research? By bringing together experts from different fields, Shew and his colleagues can address complex problems from multiple angles, leading to more innovative and effective solutions.

Some notable collaborative projects include:

- Investigating the effects of elevated CO2 and O3 on soil microbial responses in nitrogen-aggrading agroecosystems

- Studying the impact of herbicides and nutrients on the development of gray leaf spot in tall fescue

- Exploring the potential of transgenic plants for disease resistance

These collaborations not only advance the field of plant pathology but also contribute to broader areas of agricultural and environmental science.

Impact on Agricultural Practices and Crop Management

David Shew’s research has significant implications for agricultural practices and crop management strategies. His work provides valuable insights that can be directly applied to improve plant health and crop yields. Some key areas where Shew’s research has made an impact include:

- Development of disease-resistant crop varieties

- Improvement of soil management practices for disease suppression

- Enhanced understanding of pathogen population dynamics for more effective disease control

- Insights into the potential impacts of climate change on plant diseases

How can farmers benefit from Shew’s research? By incorporating the findings from Shew’s studies, farmers and agricultural professionals can make more informed decisions about crop selection, soil management, and disease control strategies. This can lead to more sustainable and productive agricultural practices.

Practical Applications

Some practical applications of Shew’s research include:

- Selection of tobacco breeding lines with improved resistance to Phytophthora nicotianae

- Optimization of irrigation practices in turfgrass management to reduce disease incidence

- Development of integrated pest management strategies based on improved understanding of pathogen ecology

- Consideration of climate change impacts in long-term crop management planning

These applications demonstrate the direct relevance of Shew’s work to real-world agricultural challenges.

Future Directions in Plant Pathology Research

As the field of plant pathology continues to evolve, David Shew’s work points to several promising directions for future research. Some areas that may see increased focus in the coming years include:

- Further exploration of the interactions between climate change and plant diseases

- Development of more sophisticated molecular tools for pathogen detection and characterization

- Investigation of novel biological control agents for sustainable disease management

- Continued research on the potential of genetic engineering for enhancing plant resistance

What challenges lie ahead for plant pathology research? As global agriculture faces increasing pressures from climate change, population growth, and emerging diseases, the work of researchers like David Shew becomes even more crucial. Future research will need to address these complex challenges while developing sustainable and effective solutions for plant disease management.

Emerging Technologies

The future of plant pathology research may also see increased integration of emerging technologies such as:

- Advanced genomics and bioinformatics tools for studying pathogen populations

- Artificial intelligence and machine learning for predicting disease outbreaks

- Precision agriculture techniques for targeted disease management

- Novel imaging technologies for early disease detection

These technologies have the potential to revolutionize our understanding of plant diseases and our ability to manage them effectively.

David Shew’s Legacy in Plant Pathology

Through his extensive research, teaching, and collaborative work, David Shew has made significant contributions to the field of plant pathology. His legacy includes:

- Advancing our understanding of soilborne fungal pathogens

- Developing innovative approaches to plant disease management

- Educating and mentoring the next generation of plant pathologists

- Fostering interdisciplinary collaboration in agricultural research

How will Shew’s work continue to influence plant pathology in the future? The methodologies, insights, and research directions established by Shew and his colleagues provide a strong foundation for future advancements in the field. As new challenges emerge in agriculture and plant health, the principles and approaches developed through Shew’s work will continue to guide researchers and practitioners alike.

David Shew’s career exemplifies the importance of combining rigorous scientific research with practical applications and education. His work not only advances our theoretical understanding of plant diseases but also provides tangible benefits to agriculture and environmental management. As the field of plant pathology continues to evolve, the contributions of researchers like David Shew will remain crucial in addressing the complex challenges of plant health and global food security.

David Shew | Entomology and Plant Pathology

Research

Research conducted in my lab is focused on the ecology and epidemiology of soilborne fungal pathogens. Our goal is to enhance short- and long-term disease management strategies based on improved understanding of the biology and ecology of soilborne pathogens. Specific investigations have emphasized: i) the effects of soil physical and chemical properties on fungal population dynamics and suppression of disease; ii) characterization of host resistance mechanisms to root pathogens and quantification of their effects on pathogen population dynamics and disease development; and iii) characterization of pathogen populations, including comparisons of populations from natural- and agro-ecosystems. We have worked in multiple host-pathogen systems to accomplish our goals, and outlines of current research projects can be viewed from the links below.

Teaching

I currently teach one of our Department’s undergraduate classes, PP 315, Principles of Plant Pathology. The course is offered each fall semester on campus and as a Distance Ed course in both fall and spring via the internet. The course provides students with an overview of plant pathogens, disease development, and disease management, while providing an opportunity for hands-on experience in working with organisms that cause plant diseases. It also offers undergraduates the opportunity to complete honors work outside of normal class requirements. Typical students in the class range from sophomores to graduate students with a very diverse set of backgrounds and interests.

The course is offered each fall semester on campus and as a Distance Ed course in both fall and spring via the internet. The course provides students with an overview of plant pathogens, disease development, and disease management, while providing an opportunity for hands-on experience in working with organisms that cause plant diseases. It also offers undergraduates the opportunity to complete honors work outside of normal class requirements. Typical students in the class range from sophomores to graduate students with a very diverse set of backgrounds and interests.

Selected Publications

- McCorkle, K. Lewis, R., and Shew, D. 2013. Resistance to Phytophthora nicotianae in tobacco breeding lines derived from Beinhart 1000. Plant Dis. 97:252-258.

- Cheng, Lei, Booker, F. L., Tu, C., Burkey, K. O., Zhou, L., Shew, H. D., Rufty, T. W., and Hu, S. 2012. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Increase Organic Carbon Decomposition Under Elevated CO2. Science 337: 1084-1087.

http://news.ncsu.edu/releases/mkhusoil/

http://news.ncsu.edu/releases/mkhusoil/ - Taylor, R. J., Pasche, J. S., Shew, H. D., Lannon, K. R., and Gudmestad, N. C. 2012. Tuber rot of potato caused by Phytophthora nicotianae: Isolate aggressiveness and cultivar susceptibility. Plant Dis. 96:693-704.

- Abad, Z.G., Ivors, K.L., Gallup, C.A., Abad, J.A., and Shew, H.D. 2011. Morphological and molecular characterization of Phytophthora glovera sp. nov. from tobacco in Brazil. Mycologia 103:341-350.

- Cheng L, Booker FL, Burkey KO, Tu C, Shew HD, Rufty, T., Fiscus, EL, Deforest, JL, Hu, S. 2011. Soil Microbial Responses to Elevated CO2 and O3 in a Nitrogen-Aggrading Agroecosystem. PLoS ONE 6(6): e21377. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021377

- Nifong, J. M., Nicholson, J. S., Shew, H. D., and Lewis, R. S. 2011. Variability for resistance to Phytophthora nicotianae within a collection of Nicotiana rustica accessions. Plant Dis. 95:1443-1447.

- Sullivan, M.

J., Parks, E. J., Cubeta, M. A., Gallup, C. A., Melton, T. A., Moyer, J.W., and Shew, H.D. 2010. An assessment of the genetic diversity in a field population of Phytophthora nicotianae with a changing race structure. Plant Dis. 94:(455-460).

J., Parks, E. J., Cubeta, M. A., Gallup, C. A., Melton, T. A., Moyer, J.W., and Shew, H.D. 2010. An assessment of the genetic diversity in a field population of Phytophthora nicotianae with a changing race structure. Plant Dis. 94:(455-460). - Gallup, C. A. and Shew, H. D. 2010. Occurrence of race 3 of Phytophthora nicotianae in North Carolina, the causal agent of black shank of tobacco. Plant Dis. 94:(557-562).

- Gregg, J.P., Peacock, C.H., Shew, H.D., Tredway, L.P., and Miller, G.L.. 2010. Herbicide and nutrient effects on the development of gray leaf spot caused by Pyricularia grisea on tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea). Proc. 2nd European Turfgrass Soc. p. 83-84.

- Kerns, J.P., Shew, H.D., Benson, D.M., and Tredway, L.P. 2009. Impact of irrigation frequency, organic matter content and creeping bentgrass cultivar on the development of Pythium root dysfunction. Intern. Turfgrass Soc. Res. Jour. 11:227-239.

- Taylor, R. J.

, Pasche, J. S., Gallup, C. A., Shew, H. D., Gudmestad, N. C. 2008. A foliar blight and tuber rot of potato caused by Phytophthora nicotianae: New occurrences and characterization of isolates. Plant Dis. 92: 492-503.

, Pasche, J. S., Gallup, C. A., Shew, H. D., Gudmestad, N. C. 2008. A foliar blight and tuber rot of potato caused by Phytophthora nicotianae: New occurrences and characterization of isolates. Plant Dis. 92: 492-503. - Elliott, P.E., Lewis, R.S., Shew, H.D, Gutierrez, W.A. and Nicholson, J.S. 2008. Evaluation of tobacco germplasm for seedling resistance to stem rot and target spot caused by Thanatephorus cucumeris. Plant Dis. 92:425-430.

- Dong, S., Shew, H. D., Tredway, L. P., Lu, J., Sivamani, E., Miller, E. S., and Qu, R. 2008. Expression of the bacteriophage T4 lysozyme gene in tall fescue confers resistance to gray leaf spot and brown patch diseases. Trangenic Res. 17:47-57.

- Shew, H. D., Fichtner, E. J., and Benson, D. M. 2007. Aluminum and plant disease. Pages 247-264, in: Mineral Nutrition and Plant Disease. L. E. Datnoff, W. H. Elmer, and D. M. Huber, eds. APS Press, The American Phytopathological Society, St.Paul. 278 pp.

- Dong, S., Tredway, L. P.

, Shew, H. D., Wang, G-L., Sivamani, E., and Qu, R. 2007. Resistance of transgenic tall fescue to two major fungal diseases. Plant Sci. 173:501-509.

, Shew, H. D., Wang, G-L., Sivamani, E., and Qu, R. 2007. Resistance of transgenic tall fescue to two major fungal diseases. Plant Sci. 173:501-509. - Ceresini, P. C., Shew, H. D., James, T. Y., Vilgalys, R. J., and Cubeta, M. C. 2007. Phylogeography of the Solanaceae-infecting Basidiomycota fungus Rhizoctonia solani AG-3 based on sequence analysis of two nuclear DNA loci. BMC Evolutionary Biology 7:163. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-163.

- Fichtner, E. J., Hesterberg, D. L., Smyth, T. J., and Shew, H. D. 2006. Differential sensitivity of Phytophthora parasitica var. nicotianae and Thielaviopsis basicola to monomeric aluminum species. Phytopathology 96:212-220.

- Gallup, C.A., M. J. Sullivan, and H. D. Shew. 2006. Black Shank of Tobacco. The Plant Health Instructor. DOI: 10.1094/PHI-I-2006-0717-01. APS web site: http://www.apsnet.org/education/LessonsPlantPath/blackShank/default.htm.

- Sullivan, M. J., Melton, T. A., and Shew, H. D. 2005. Fitness of races 0 and 1 of Phytophthora parasitica var.

nicotianae. Plant Dis. 89:1220-1228.

nicotianae. Plant Dis. 89:1220-1228. - Sullivan, M. J., Melton, T. A., and Shew, H. D. 2005. Managing the race structure of Phytophthora parasitica var. nicotianae with cultivar rotation. Plant Dis. 89:1285-1294.

- Fichtner, E.J., Benson, D.M., Diab, H.G., and Shew. H.D. 2004. Abiotic and biological suppression of Phytopththora parasitica in a horticultural medium containing composted swine waste. Phytopathology 94:780-788.

- Uriarte, R.F., Shew, H.D., and Bowman, D.C. 2004. Effect of soluble silica on brown patch and dollar spot of creeping bentgrass. J. Plant Nutr. 27:325-339.

- Ceresini, P.C., Shew, H.D. Vilgalys, R., Rosewich-Gale, U. L., and Cubeta, M.A. 2003. Detecting migrants in populations of Rhizoctonia solani anastomosis group 3 from potato in North Carolina using multilocus genotype probabilities. Phytopathology 93:610-615.

- Johnson, E. S., Wolff, M. F., Wernsman, E. A., Atchley, W. R., and Shew, H. D. 2002. Origin of the black shank resistance gene, Ph, in tobacco cultivar Coker 371-Gold.

Plant Dis. 86:1080-1084.

Plant Dis. 86:1080-1084. - Ceresini, P. C., Shew, H. D., Vilgalys, R. J. and Cubeta, M. A. 2002. Genetic diversity of Rhizoctonia solani AG-3 from potato and tobacco in North Carolina. Mycologia 94:437-449.

- Ceresini, P. C., Shew, H. D., Vilgalys, R. J., Rosewich, U. L., and Cubeta, M. A. 2002. Genetic structure of populations of Rhizoctonia solani AG-3 on potato in eastern North Carolina. Mycologia 94:450-460.

- Fichtner, E. J., Hesterberg, D. L., and Shew, H. D. 2001. Nonphytotoxic aluminum-peat complexes suppress Phytophthora parasitica. Phytopathology 91:1092-1097.

- Shew, H. D. 2001. Direct penetration. Pages 311-312. in: Encyclopedia of Plant Pathology. O. C. Maloy and T. D. Murray, eds. John Wiley and Sons, Inc. New York. Vol. 1. 598 pp.

- Shew, H. D. 2001. Indirect penetration. Page 571. in: Encyclopedia of Plant Pathology. O. C. Maloy and T. D. Murray, eds. John Wiley and Sons, Inc. New York. Vol. 1. 598 pp.

- Shew, H. D. 2001. Infection.

Pages 572-574. in: Encyclopedia of Plant Pathology. O. C. Maloy and T. D. Murray, eds. John Wiley and Sons, Inc. New York. Vol. 1. 598 pp.

Pages 572-574. in: Encyclopedia of Plant Pathology. O. C. Maloy and T. D. Murray, eds. John Wiley and Sons, Inc. New York. Vol. 1. 598 pp. - Shew, H. D. 2001. Infection courts. Pages 574-575. in: Encyclopedia of Plant Pathology. O. C. Maloy and T. D. Murray, eds. John Wiley and Sons, Inc. New York. Vol. 1. 598 pp.

- Shew, H. D. 2001. Penetration. Pages 747-748. in: Encyclopedia of Plant Pathology. O. C. Maloy and T. D. Murray, eds. John Wiley and Sons, Inc. New York. Vol. 2. 769 pp.

- Harrison, U. J., and Shew, H. D. 2001. Effects of soil pH and nitrogen fertility on the population dynamics of Thielaviopsis basicola. Plant Soil 228(2):147-155.

- Hudyncia,J., Shew, H. D., Cody, B. R., and Cubeta, M. A. 2000. Evaluation of wounds as predisposing factors to infection of cabbage by Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Plant Dis. 84:316-320.

- Gutierrez, W. A., and Shew, H. D. 2000. Factors that affect development of Sclerotinia collar rot on tobacco seedlings grown in greenhouses.

Plant Dis. 84:1076-1080.

Plant Dis. 84:1076-1080. - Shoemaker, P. B. and Shew, H. D. 1999. Major tobacco diseases: Fungal and bacterial diseases. Pages 183-197, in: Tobacco: Production, chemistry and technology. D. L. Davis and M. T. Nielsen, eds. Blackwell Science, Oxford.

- Gutierrez, W. A., and Shew, H. D. 1998. Identification and quantification of ascospores as the primary inoculum for the collar rot disease of greenhouse-produced tobacco seedlings. Plant Dis. 82:485-490.

- Hood, M. E., and Shew, H. D. 1997. Initial cellular interactions between Thielaviopsis basicola and tobacco root hairs. Phytopathology 87:228-235.

- Hood, M. E. and Shew, H. D. 1997. The role of parasitism in the ecology of Thielaviopsis basicola. Phytopathology 87:1214-1219.

- Hood, M. E., and Shew, H. D. 1997. The influence of nutrients on development, resting hyphae and aleuriospore induction of Thielaviopsis basicola. Mycologia 89:793-800.

- Gutierrez, W. A., and Shew, H. D. 1997. Sources of inoculum and management of diseases of greenhouse-produced tobacco seedlings.

Plant Dis. 81:604-606.

Plant Dis. 81:604-606. - Carlson, S. R., Wolff, M. F., Shew, H. D., and Wernsman, E. A. 1997. Inheritance of resistance to race 0 of Phytophthora parasitica var. nicotianae from the flue-cured tobacco cultivar ‘Coker 371-Gold’. Plant Dis. 81:1269-1274.

- Hood, M. E., and Shew, H. D. 1996. Pathogenesis of Thielaviospsis basicola on a susceptible and a resistant cultivar of burley tobacco. Phytopathology 86:38-44.

- Hood, M. E., and Shew, H. D. 1996. Applications of KOH-aniline blue fluorescence in the study of plant-fungal interactions. Phytopathology 86:704-708.

- Abad, G., Shew, H. D., Grand, L. F., and Lucas, L. T. 1995. A new species of Pythium producing multiple oospores isolated from bentgrass in North Carolina. Mycologia 87:896-901.

- Jones, K. J. and Shew, H. D. 1995. Early season root production and zoospore infection of cultivars of flue-cured tobacco that differ in level of partial resistance to Phytophthora parasitica var. nicotianae. Plant and Soil 119:55-61.

- Shew, H. D. and Melton, T. A. 1995. Target spot of tobacco. Plant Dis. 79:6-11.

- Wilkinson, C. A., Shew, H. D., and Rufty, R. C. 1995. Evaluation of components of partial resistance to black root rot in burley tobacco. Plant Dis. 79:738-741.

- Abad, Z. G., Shew, H. D. and Lucas, L. T. 1994. Characterization and pathogenicity of Pythium species isolated from turfgrass with symptoms of root and crown rot in North Carolina. Phytopathology 84:913-921.

- Meyer, J. R., Shew, H. D., and Harrison, U. J. 1994. Inhibition of germination and growth of Thielaviopsis basicola by aluminum. Phytopathology 84:598-602.

- Shew, H. D., and Shew, B. B. 1994. Host Resistance. Pages 244-275 in: Epidemiology and management of root diseases. C. L. Campbell and D. M. Benson, eds. Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg, 344 pp.

- Shew, H. D. and Shoemaker, P. B. 1993. Effects of host resistance and soil fumigation on populations of Thielaviopsis basicola and development of black root rot on burley tobacco.

Plant Dis. 77:1035-1039.

Plant Dis. 77:1035-1039. - Johnk, J. S., Jones, R. K., Shew, H. D., and Carling, D. E. 1993. Characterization of populations of Rhizoctonia solani AG-3 from potato and tobacco. Phytopathology 83:854-858.

- Shew, H. D., and Lucas, G. B. 1991. Compendium of Tobacco Diseases. APS Press, St. Paul. 90 pp.

- Meyer, J. R., and Shew, H. D. 1991. Soils suppressive to black root rot of burley tobacco, caused by Thielaviopsis basicola. Phytopathology 81:946-954.

- Meyer, J. R., and Shew, H. D. 1991. Development of black root rot on burley tobacco in relation to pathogen population, host resistance and soil chemistry. Plant Dis. 75:601-605.

- Shew, H. D., and Main, C. E. 1990. Infection and development of target spot of flue-cured tobacco caused by Thanatephorus cucumeris. Plant Dis. 74:1009-1013.

- Meyer, J. R., Shew, H. D., and Shoemaker, P. B. 1989. Populations of Thielaviopsis basicola and the occurrence of black root rot on burley tobacco in western North Carolina.

Plant Dis. 73:239-242.

Plant Dis. 73:239-242. - Shew, H. D. 1987. Effect of host resistance on spread of Phytophthora parasitica var. nicotianae and the subsequent development of tobacco black shank under field conditions. Phytopathology 77:1090-1093.

Education

B.S., Biology, Greensboro College

M.S., Plant Pathology, North Carolina State University

Ph.D, Plant Pathology, North Carolina State University

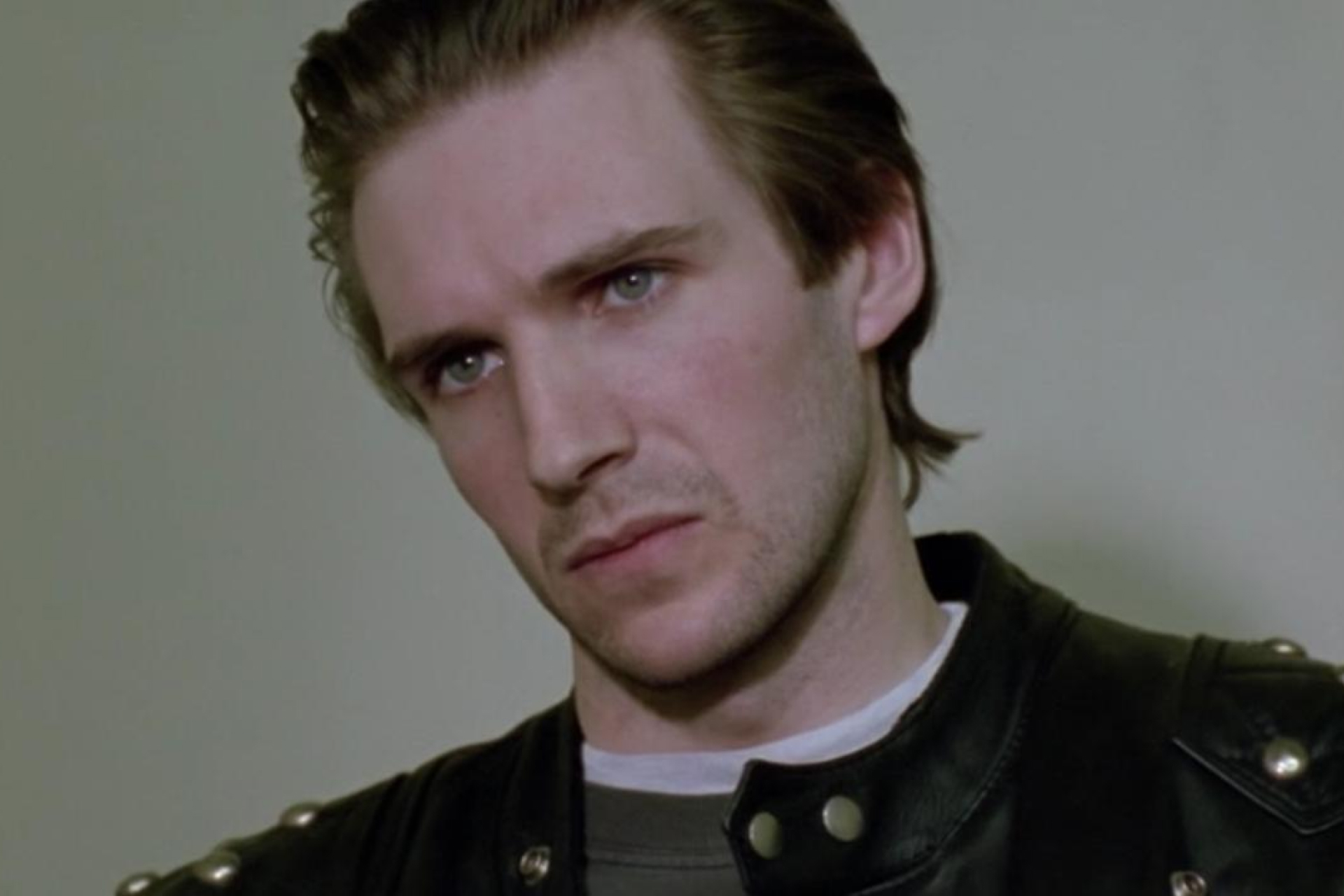

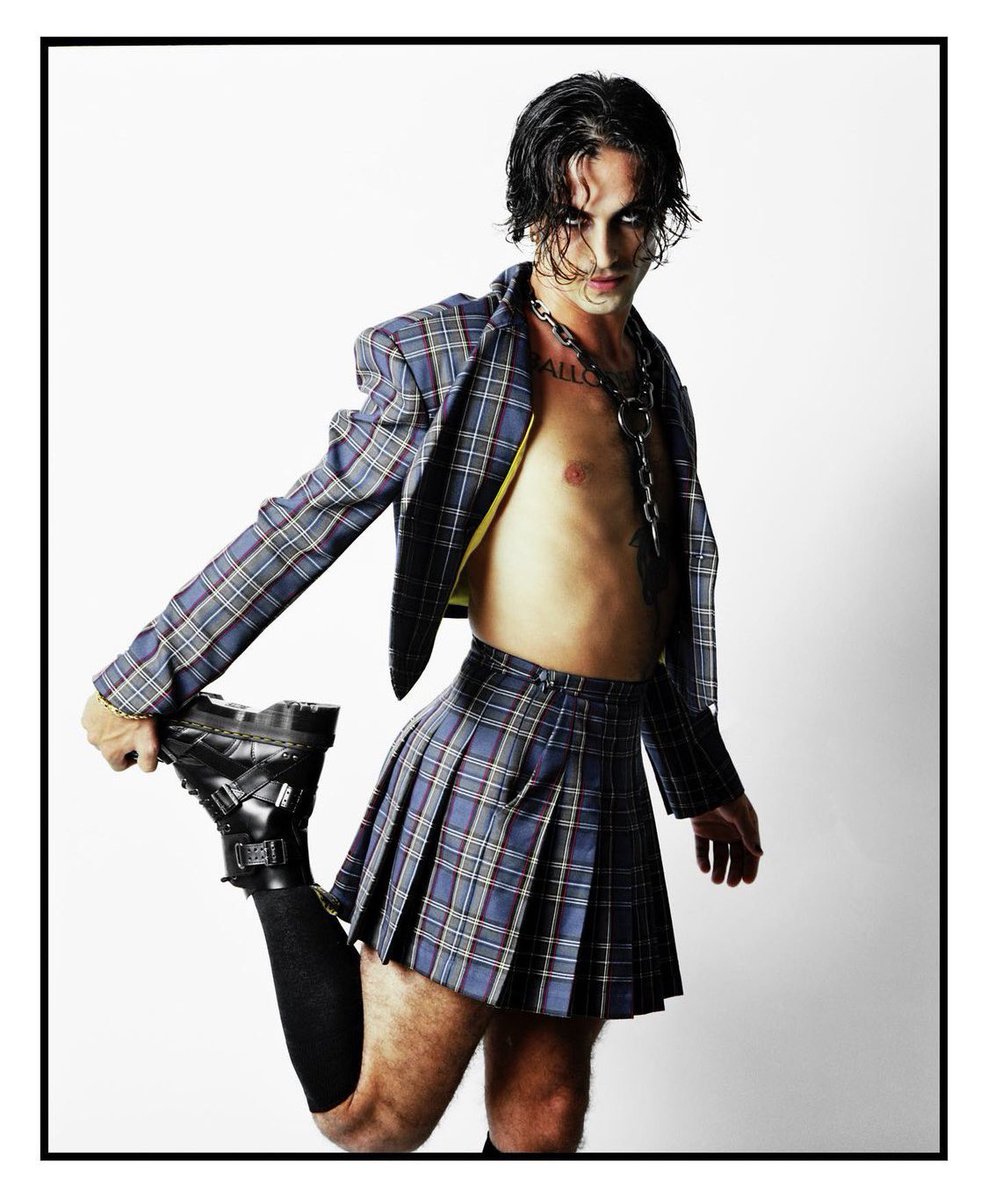

David Shew – 2023 – Men’s Lacrosse

-

Bio -

Related -

Stats -

Historical

Biography

2023:

- Did not appear in any games on the season

2022:

- Played in five games on the year

- Scored once and added an assist on the season

- Tallied his assist against Delaware

- Scored in the win against Mount St.

Mary’s

Mary’s

2021:

- Did not appear in any games on the season

High School/Personal: All-Catholic Second Team selection… Offensive MVP… Team’s leading scorer… Four-year varsity letterwinner.

Statistics

Season:

Season Statistics

Season Statistics

No statistics available for this season.

Career Statistics

There are no statistics available for this player.

Historical Player Information

-

2021Freshman

Attack

6’1″

190 lbs

-

2022Sophomore

Attack

6’1″

194 lbs

-

2023Junior

Attack

6’1″

194 lbs

©2023 Saint Joseph’s University Athletics

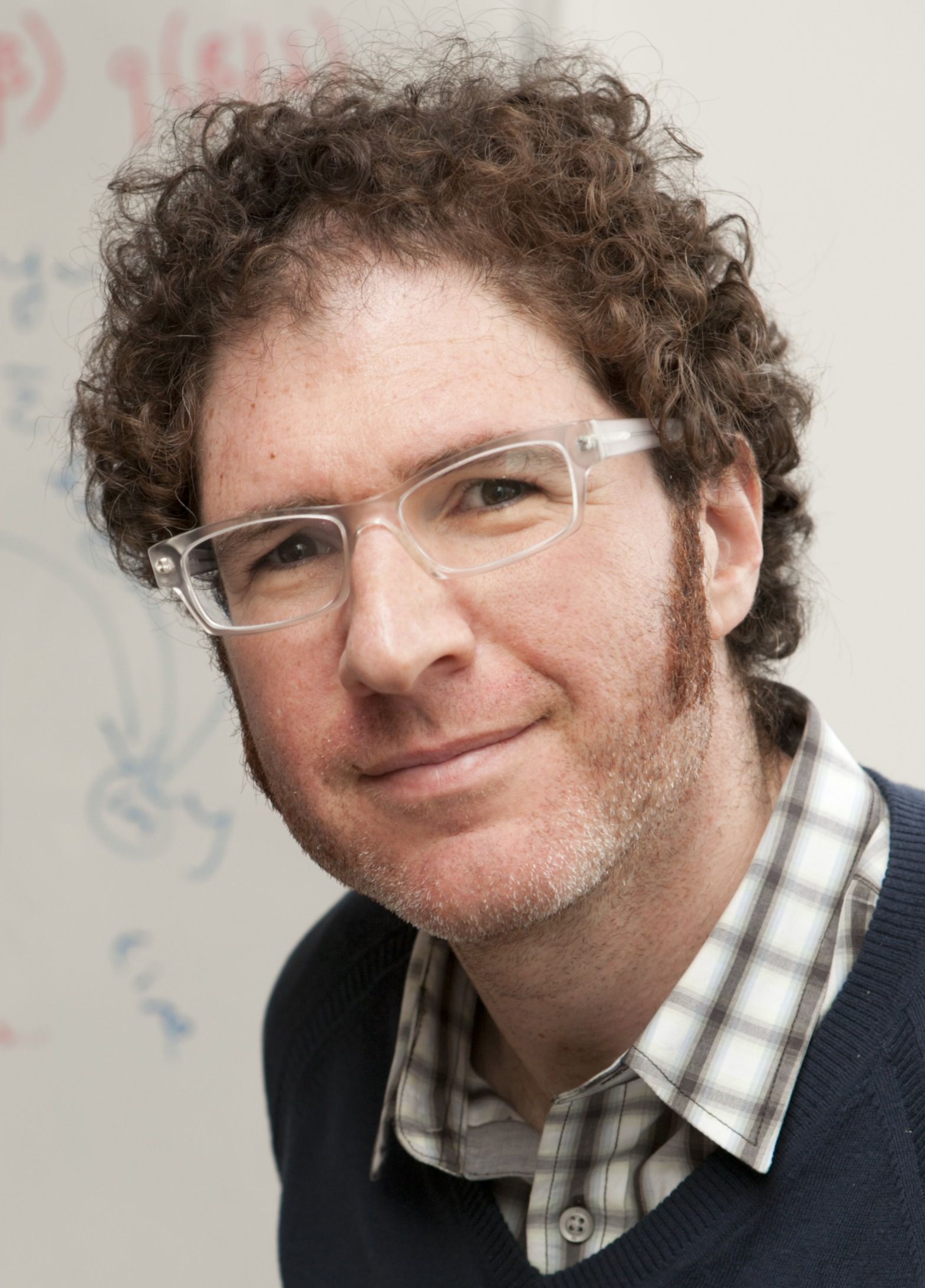

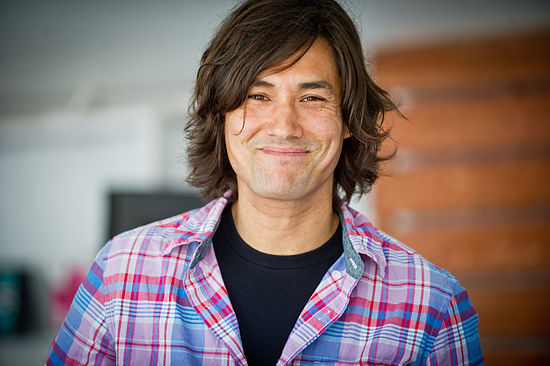

how a scientist David Shaw applied mathematical methods in trading and earned $ 7 billion – Stories on vc.

ru In 2021, the fund manages $ 60 billion in assets, and Shaw stepped away from management and is engaged in structural biology – so as not to be stupid.

ru In 2021, the fund manages $ 60 billion in assets, and Shaw stepped away from management and is engaged in structural biology – so as not to be stupid.

42,580

views

Networth Times

Scientist on a Ferrari

David Shaw was born in Los Angeles in 1951 to a theoretical physicist and artist. His parents divorced when he was 12, and his mother remarried to finance teacher Irwin Pfeffer. The stepfather introduced the boy to economic theories and often took him to work at the University of California at San Diego.

Shaw has been trying to earn money since he was a teenager:

- At the age of 12, he borrowed $100 from his friends to make a horror movie that he wanted to show to his friends. The ticket was supposed to cost 50 cents. But the plan did not come true – in the laboratory, the film was lost during development.

- In high school, I bought three sewing machines and hired classmates to sew ties.

Shaw wanted to sell them to shops, but no one bought them.

Shaw wanted to sell them to shops, but no one bought them.

After high school in 1968, he entered the University of California, where he received a bachelor’s degree in applied physics and computer science. In 1973, he studied computer science as a graduate student at Stanford.

During his student years, he founded a company that created compilers – programs that convert program code into machine code. This show began to earn. But his supervisor did not like this: he hinted that it would be difficult to combine study and entrepreneurship, and advised him to choose between science or business.

Shaw chose science: in 1980 he defended his dissertation, received a PhD and got a job as an assistant professor at Columbia University in New York. According to the memoirs of a colleague, the scientist came to work in a Ferrari and hired a personal PR manager. And according to Wired, he was a long-haired and bearded surf musician.

At the university he worked on an experimental parallel computer project. Shaw said that he wanted to make a machine that would work like a human brain: if an ordinary computer has a powerful, but only one processor, then its development should have consisted of several slow processors working simultaneously – like neurons.

Shaw said that he wanted to make a machine that would work like a human brain: if an ordinary computer has a powerful, but only one processor, then its development should have consisted of several slow processors working simultaneously – like neurons.

According to Shaw, this was the first such project. For him, he received a grant from the state, assembled a team of 35 people and built the first prototype. When it was ready, it turned out that the money was not enough – another $ 10-20 million was needed. The show began to look for them, offered the idea to investors, but no one invested.

Job at Morgan Stanley

In 1986, a scientist who never found funding for his project was asked to be part of a research team at Morgan Stanley. He was offered a salary six times the university salary. He agreed: he shaved off his beard, put on a suit and “ran off to Wall Street.”

NYPost

Shaw worked in a department that used mathematical methods of quantitative analysis to look for anomalies in a large amount of securities data from which the bank could benefit. The method was called “statistical arbitrage”.

The method was called “statistical arbitrage”.

At Morgan Stanley, a scientist began to use a supercomputer: several parallel processors simultaneously searched for anomalies. He had no experience in trading, but the leaders promised to give him the opportunity to develop his own strategies – “make real money.”

I was drawn to the challenge of beating the market. I was told from childhood that this was impossible, but here they say that they know how to do it.

David Shaw

He offered his colleagues and management of Morgan Stanley his ideas on how to work better. However, he realized that he would not be able to sell them in a conservative investment bank, and left the company in 1988.

After his departure, the group did worse, in the same year the division’s budget was cut from $900 million to $300 million. A year later, Morgan Stanley completely disbanded it.

D. E. Shaw & Co Investment Company – Algorithmic or Quantum Trading

In 1988, Shaw founded the investment company D. E. Shaw & Co. Its initial capital was $28 million, the largest investors were the hedge funds Paloma Partners and Continental Casualty.

E. Shaw & Co. Its initial capital was $28 million, the largest investors were the hedge funds Paloma Partners and Continental Casualty.

Paloma Parnets CEO Donald Sussman explained why he invested in Shaw’s company: “He’s the smartest man I’ve ever met. I’m new to him.”

The Foundation used the methods of quantum and quantitative trading: actions were performed not by people, but by ultra-fast computer systems. They can more accurately predict the best trades and choose when to make them. This saves time and effort, because the algorithm does the job faster than a human.

Like playing roulette from the point of view of the casino owner: the chances of winning at each turn of the wheel at the casino are slightly more than 50%, but thanks to the laws of probability theory, the profit of the house grows in the long run. According to Fortune, the fund concluded the first deal six months after the launch, its details and amounts are unknown.

At the beginning of the work, there were six employees who worked in the attic of a house near the Greenwich Village area. The founder noted that it was the first investment bank whose office was above a “leftist bookstore.”

If someone tripped over one of the cables, they could stop trading for ten minutes until the system was reconnected.

Employee of D. E. Shaw & Co.

Hiring in the company was strict. All applicants were offered to solve absurd tasks not directly related to the position:

No favors were given to proven candidates: For example, former US Treasury Secretary and Harvard President Lawrence Summers had to solve puzzles like everyone else. And in 1990 D.E. Shaw & Co has hired future Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos.

One of my partners came in one day and said, “I just had an interview with a great candidate named Jeff Bezos. We don’t have a job for him, but I have a feeling he’s going to make someone rich someday, so let’s meet him and have a chat.

”

David Shaw

The head of the investment company spoke with Bezos: according to Shaw, he turned out to have a powerful intellect, huge creative potential and a rare entrepreneurial flair. “I told my partner that he was right: even if we don’t have a position for him, but Jeff needs to be hired, and then think about what to do with him.”

The future founder of Amazon became vice president of the company and left in 1994.

Jeff Bezos at 1990s twitter.com

By 1996, the investment firm had 300 employees, and its annual revenue was $600 million . In 1997, D. E. Shaw & Co had a net worth of $90,094 $800 million 90,095 and was a 5% daily trader on the New York Stock Exchange.

Shaw himself said that while managing an investment company, over time he felt dumber and solved problems in computer science in his spare time. And in 2001, he completely withdrew from management and appointed six employees in his place – most of them did not work in the financial sector before D. E. Shaw & Co.

E. Shaw & Co.

After Shaw’s departure, the company continued to grow:

- In 2001, the company launched a new hedge fund called Composite. From the moment of its foundation until 2020, its profitability averaged 11.7% per annum.

- In 2004, she created a new Oculus fund, the yield of which is 12.5% per annum.

The S&P 500, for example, averaged 7.9% per annum from 2001 to 2020.

Office in India D. E. Shaw & Co

In 2007, the founder sold 20% of his shares to Lehman Brothers for $775 million. As of March 2021, he still owns 63% of the firm. D. E. Shaw & Co funds totaled $60 billion in September

In 2019, D. E. Shaw & Co had 1,200 employees, including 87 PhDs.

Work and life outside D.E. Shaw & Co

In 1994, the scientist was one of the advisers to the Bill Clinton administration on computer technology. In 2007, he became Obama’s science advisor.

In 2007, he became Obama’s science advisor.

David Shaw and David Siegel Bloomberg

While working on Wall Street for his foundation, he began collaborating with Rich Frisner, a Columbia University friend and biochemist. Shaw decided that his knowledge of algorithms and computers could help solve the problem of protein folding.

In 2001, after leaving D.E. Shaw & Co, he founded D.E. Shaw Research – She develops new algorithms for high-speed molecular modeling of proteins and uses them in the development of medicines. The scientist’s team consists of computer scientists, engineers, computer chemists and biologists, applied mathematicians and architects.

columbia.edu

In 2008 D.E. Shaw Research launched the Anton supercomputer, which was used for simulations. The device was named after the Dutch inventor of the microscope, Anton van Leeuwenhoek. Compared to the existing BlueGen / L at that time, the device counted a thousand times faster.

In 2009, the scientist admitted that his company was not yet ready to develop specific drugs, and its interest lay in the field of fundamental research. A year later, Anton was donated to biochemists at the Pittsburgh Science Center.

In 2014, DE Shaw Research created a second supercomputer, the Anton 2, which was able to simulate protein folding, signaling, and some changes in the structure of molecules. About 150 academic groups in the US have benefited from the company’s developments.

In October 2021, Forbes estimates Shaw’s fortune at $7.5 billion. He still owns control of D.E. Shaw & Co, and he himself continues to engage in microbiological research.

Treasurer David Shaw

The exchange field of activity allows almost every person to earn huge money, regardless of what profession or skills they had before they first made a deal.

However, despite the abundance of different approaches to its analysis, people associated with the exact sciences, and especially mathematicians and economists, most often achieve success.

The acquired skills of logical thinking become an excellent basis for obtaining new knowledge and skills.

What is most surprising in the biographies of successful people is the fact that successful teachers, scientists or people closely associated with programming suddenly leave their comfort zone and achieve stunning success in stock trading.

Actually in this article you will get acquainted with the biography of David Shaw, one of the most influential billionaires in the United States of America.

David Shaw was born on March 29, 1951. It is worth noting that almost nothing is known about the early years of the future stock exchange genius, except that from childhood he showed phenomenal abilities in mathematics and the exact sciences.

David Shaw was educated at the University of California, where he successfully earned a bachelor’s degree with honors.

High academic achievement, as well as a great love for science led David to teach and receive a Ph. D. in philosophy from Stanford University.

D. in philosophy from Stanford University.

After completing his PhD, David Shaw taught for many years teaching computer science to students at Columbia University.

At the same university, he conducted scientific activities, conducting various computational studies at that time with the NON-VON supercomputer.

Also before he began his studies at Columbia University, he founded the Stanford Systems Corporation, which was engaged in computing and computer technology.

At Columbia University proper, David Shaw was promoted to faculty dean.

Exchange career

David Shaw’s trading career began in 1986. At that time, Shaw was a well-known computer scientist, and the largest Morgan Stanley fund at that time was looking for an experienced vice president. The task of which was to control the automated trading group for asset management.

Naturally, the salary of a teacher and manager is completely incomparable, so David Shaw responded to the offer and coped with his duties quite well.

With just two years at Morgan Stanley, David Shaw was able to gain the experience he needed to reach his potential.

Faced with resistance to implement his own ideas at Morgan Stanley, David Shaw decides to leave his position in the company and start an independent career.

In 1988, David Shaw founded his company called DE Shaw & Co, which became the flagship of computer-based robotic trading.

The hedge fund was engaged in buying stocks, bonds and other various securities based on a computerized algorithm invented by David Shaw.

The high profitability of the hedge fund caused a huge response from investors, moreover, in order to hedge their risks, many funds began to actively invest in David Shaw’s company.

However, the sale of shares in Lehman Brothers was a huge boost in customer acquisition, and the proceeds greatly expanded the company’s trading capabilities.

Huge capital, as well as authority, allowed Shaw to enter politics and influence the state from within.

http://news.ncsu.edu/releases/mkhusoil/

http://news.ncsu.edu/releases/mkhusoil/ J., Parks, E. J., Cubeta, M. A., Gallup, C. A., Melton, T. A., Moyer, J.W., and Shew, H.D. 2010. An assessment of the genetic diversity in a field population of Phytophthora nicotianae with a changing race structure. Plant Dis. 94:(455-460).

J., Parks, E. J., Cubeta, M. A., Gallup, C. A., Melton, T. A., Moyer, J.W., and Shew, H.D. 2010. An assessment of the genetic diversity in a field population of Phytophthora nicotianae with a changing race structure. Plant Dis. 94:(455-460). , Pasche, J. S., Gallup, C. A., Shew, H. D., Gudmestad, N. C. 2008. A foliar blight and tuber rot of potato caused by Phytophthora nicotianae: New occurrences and characterization of isolates. Plant Dis. 92: 492-503.

, Pasche, J. S., Gallup, C. A., Shew, H. D., Gudmestad, N. C. 2008. A foliar blight and tuber rot of potato caused by Phytophthora nicotianae: New occurrences and characterization of isolates. Plant Dis. 92: 492-503. , Shew, H. D., Wang, G-L., Sivamani, E., and Qu, R. 2007. Resistance of transgenic tall fescue to two major fungal diseases. Plant Sci. 173:501-509.

, Shew, H. D., Wang, G-L., Sivamani, E., and Qu, R. 2007. Resistance of transgenic tall fescue to two major fungal diseases. Plant Sci. 173:501-509. nicotianae. Plant Dis. 89:1220-1228.

nicotianae. Plant Dis. 89:1220-1228. Plant Dis. 86:1080-1084.

Plant Dis. 86:1080-1084. Pages 572-574. in: Encyclopedia of Plant Pathology. O. C. Maloy and T. D. Murray, eds. John Wiley and Sons, Inc. New York. Vol. 1. 598 pp.

Pages 572-574. in: Encyclopedia of Plant Pathology. O. C. Maloy and T. D. Murray, eds. John Wiley and Sons, Inc. New York. Vol. 1. 598 pp. Plant Dis. 84:1076-1080.

Plant Dis. 84:1076-1080. Plant Dis. 81:604-606.

Plant Dis. 81:604-606.

Plant Dis. 77:1035-1039.

Plant Dis. 77:1035-1039. Plant Dis. 73:239-242.

Plant Dis. 73:239-242. Mary’s

Mary’s Shaw wanted to sell them to shops, but no one bought them.

Shaw wanted to sell them to shops, but no one bought them. ”

”