What is the Chesapeake Summer Rowing Camp. Who can participate in the camp. What activities are included in the program. How much does the camp cost. What should participants bring to the camp. Where is the camp located. How long does the camp last.

Discover the Exciting World of Rowing at Chesapeake Summer Camp

The Chesapeake Summer Rowing Camp, organized by Hickory Crew, offers an incredible opportunity for students to dive into the thrilling sport of rowing. This two-week program is designed to introduce young athletes to the fundamentals of crew while fostering teamwork, physical fitness, and new friendships.

Camp Details at a Glance

- Dates: August 7th – 18th, 2023

- Time: Monday – Friday, 5 PM – 7 PM

- Location: Atlantic Yacht Basin, 2615 Basin Rd, Chesapeake

- Cost: $100 per week

- Eligibility: Open to all 7th-12th graders, including local school and home-schooled students

Are you wondering about the benefits of joining this summer camp? Participants will not only learn a new sport but also receive a free camp t-shirt and a $200 discount on their first season dues if they decide to join the Hickory Crew club.

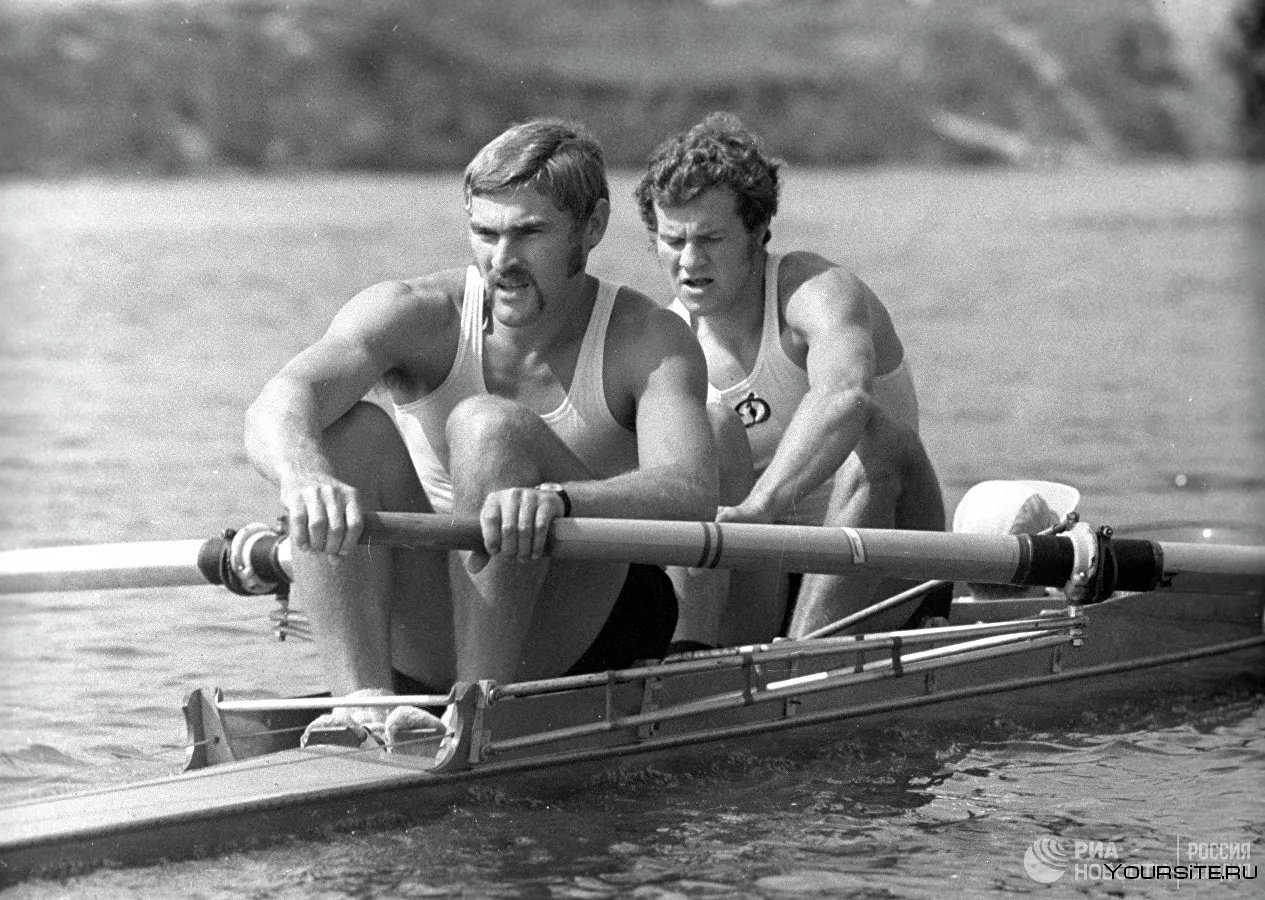

What to Expect: A Journey from Novice to Rower

Many newcomers to the camp may have little to no experience with rowing. Fear not! The program is designed to guide participants through every step of the process, from understanding the basics to getting out on the water.

Day 1 & 2: Laying the Foundation

The first two days of camp focus on introducing participants to the equipment and teaching the fundamental rowing stroke. What tools will campers use to learn? They’ll start with rowing machines called ergometers or ‘ergs’. These machines provide a stable platform for mastering the sequence of body movements required for rowing without the challenge of balancing in a boat.

Towards the end of the second day, participants will progress to the ‘row box’ – a section of a boat used to teach oar handling skills. This step is crucial in preparing campers for the real thing.

Day 3 and Beyond: Taking to the Water

From the third day onwards, the excitement really begins as campers start getting out on the water. How will this transition work? New rowers will be paired with experienced varsity team members in boats that can accommodate eight rowers. This arrangement allows novices to gradually build their skills and confidence under the guidance of more experienced peers.

As the days progress, participants will spend more time actively rowing, with coaches in motor launches providing instruction and ensuring safety throughout the sessions.

Safety First: Ensuring a Secure Environment for All Participants

Safety is a top priority at the Chesapeake Summer Rowing Camp. While rowing is generally a safe sport, certain precautions are in place to protect all participants.

Swimming Ability

Is swimming proficiency required for the camp? While it’s unlikely that participants will end up in the water, being a competent swimmer is essential. Campers should be able to float, tread water, and swim short distances.

Medical Considerations

Can students with pre-existing conditions participate? In most cases, yes. Conditions such as asthma are not disqualifiers, as long as the participant is cleared for physical activity by a medical professional.

On-Water Safety

How is safety ensured during water sessions? Coaches in motor launches accompany the boats at all times. They are in constant communication with practice parents onshore and have marine radios to communicate with other boaters if necessary.

Gearing Up: What to Bring and Wear for Optimal Performance

Proper attire and equipment are crucial for a comfortable and successful rowing experience. Here’s what participants should keep in mind:

Clothing

What’s the ideal outfit for rowing? Athletic attire that is snug but not restrictive is best. Baggy shorts should be avoided as they can get caught in the sliding seat. Similarly, overly long shirts can interfere with movement.

Footwear

What type of shoes are appropriate? Athletic shoes are a must. While there isn’t much running involved, participants will do some as part of their warm-up starting from day two. Sandals, crocs, and flip-flops are not allowed. Don’t forget to bring socks, as wet feet are a common occurrence in this water sport.

Sun Protection

How can participants protect themselves from the sun? Hats, sunglasses, and sunscreen are highly recommended. The canal runs east-west, so when rowing eastward in the afternoon, the sun can be quite intense. It’s advisable not to bring expensive sunglasses, as there’s always a risk they could end up at the bottom of the canal.

Bug Repellent

Should participants bring bug spray? If you’re prone to insect bites, it’s a good idea to bring some bug repellent.

Weather Considerations: Rowing Rain or Shine

The Chesapeake Summer Rowing Camp operates in various weather conditions, but safety always comes first.

Will the camp take place in rainy conditions? Light rain or mist usually won’t stop the rowing activities. However, heavy downpours or lightning will result in the cancellation of that day’s session. The camp organizers constantly monitor weather conditions to ensure participant safety.

In cases of passing showers, activities may be paused, with participants waiting in the boathouse until it’s safe to resume. For more severe weather events, the day’s activities might be cancelled entirely.

Beyond the Basics: Additional Camp Features and Benefits

The Chesapeake Summer Rowing Camp offers more than just an introduction to rowing. It provides a comprehensive experience that can have lasting benefits for participants.

Physical Fitness

How does rowing contribute to overall fitness? Rowing is a full-body workout that engages all major muscle groups. It combines cardiovascular endurance with strength training, making it an excellent sport for overall physical fitness.

Mental Focus

Does rowing have mental benefits? Absolutely. Rowing requires significant mental focus and concentration. Participants learn to synchronize their movements with their teammates, developing discipline and mental fortitude.

Teamwork and Social Skills

How does the camp foster social interaction? The nature of rowing as a team sport naturally encourages collaboration and communication. Participants will work closely with their peers, fostering new friendships and developing crucial teamwork skills.

Introduction to Competitive Rowing

Can the camp serve as a springboard to competitive rowing? Indeed, it can. For those who discover a passion for rowing during the camp, joining the Hickory Crew club afterwards is an excellent way to continue developing their skills and potentially compete at a higher level.

Location and Logistics: Navigating the Camp Experience

Understanding the camp’s location and logistics is crucial for a smooth experience. Here’s what participants and parents need to know:

Camp Location

Where exactly is the camp held? The Chesapeake Summer Rowing Camp takes place at the Atlantic Yacht Basin, located at 2615 Basin Rd in Chesapeake, near the Great Bridge drawbridge. The camp rows on the Albemarle & Chesapeake Canal.

Parking

Where should parents park when dropping off participants? Parking is available on the grass along the road or on the fire road. It’s important to note that parking on AYB’s paved lot is not permitted.

Check-In Process

What happens when participants arrive at the camp? Upon arrival, campers will check in at the Hickory Crew tent. Staff will be available to answer questions, ensure all paperwork is complete, and escort participants to the boathouse. Parents are welcome to accompany their children during this process.

Facility Tour

Will participants receive an orientation to the facilities? Yes, new campers will be given a short tour of the facilities, including an introduction to the boats and various tools used in rowing.

Financial Aspects: Understanding the Costs and Funding

The Chesapeake Summer Rowing Camp offers an affordable introduction to the sport of rowing, but it’s important to understand the financial structure of the program.

Camp Cost

How much does the camp cost? The camp fee is $100 per week, making it a total of $200 for the full two-week program.

Included Benefits

What’s included in the camp fee? In addition to the daily rowing instruction, participants receive a free camp t-shirt.

Hickory Crew Funding

How is Hickory Crew funded? It’s important to note that Hickory Crew is 100% funded by donations, fundraising, and member dues. The organization receives no funding from Chesapeake Public Schools.

Discount for Continued Participation

Are there any incentives for joining Hickory Crew after the camp? Yes, if a student decides to join the Hickory Crew club after attending the summer camp, they will receive a $200 discount on their first season dues.

Preparing for Success: Tips for New Rowers

For those new to rowing, the prospect of joining the Chesapeake Summer Rowing Camp might seem daunting. Here are some tips to help new participants prepare and make the most of their experience:

Physical Preparation

How can participants prepare physically for the camp? While no specific fitness level is required to start, it’s beneficial to engage in some general cardiovascular exercise and strength training in the weeks leading up to the camp. Activities like jogging, cycling, or swimming can help build endurance.

Mental Preparation

What mindset should new rowers adopt? Approach the camp with an open mind and a willingness to learn. Rowing is a unique sport that may feel unfamiliar at first, but with patience and practice, skills will develop quickly.

Hydration and Nutrition

How should participants fuel their bodies for rowing? Staying hydrated is crucial, especially when exercising outdoors. Bring a water bottle to each session. Eating a light, balanced meal about an hour before camp can provide the necessary energy without causing discomfort during rowing.

Rest and Recovery

Is rest important during the camp? Absolutely. Rowing can be physically demanding, especially for beginners. Ensure you get adequate sleep each night to allow your body to recover and prepare for the next day’s activities.

Beyond the Camp: Continuing Your Rowing Journey

The Chesapeake Summer Rowing Camp is just the beginning of what could be a lifelong passion for rowing. Here’s how participants can continue their rowing journey after the camp concludes:

Joining Hickory Crew

How can participants continue rowing after the camp? The most direct way is to join the Hickory Crew club. Remember, camp participants receive a $200 discount on their first season dues if they decide to join.

School Programs

Are there rowing programs in local schools? While Hickory Crew isn’t directly affiliated with Chesapeake Public Schools, some schools may have their own rowing programs or clubs. It’s worth checking with your school’s athletic department.

Competitive Opportunities

Can participants eventually compete in rowing? Yes, for those who develop a passion for the sport, there are numerous competitive opportunities in rowing, from local regattas to national competitions and even collegiate rowing.

Long-term Benefits

What are the long-term benefits of continuing with rowing? Rowing is a lifelong sport that offers numerous physical and mental health benefits. It’s also a great addition to college applications and can even lead to scholarship opportunities at some universities.

The Chesapeake Summer Rowing Camp offers an exciting gateway into the world of rowing. Whether you’re looking for a new summer activity, a way to stay fit, or the start of a competitive athletic career, this camp provides the perfect opportunity to dip your oar into the water and discover the joys of rowing.

Summer Camp 2023 | Hickory Crew

AUGUST 7TH – 18TH

MONDAY – FRIDAY

5 PM – 7 PM

Summer Camp is open to all 7th-12th Graders All local school and home-schooled students are welcome.

Hickory Crew is 100% funded by donations, fundraising, and member dues. We receive absolutely NO funding from Chesapeake Public Schools.

If your student joins our club, after attending our crew camp, they will receive a $200 discount on their first season dues.

FREE

CAMP

TSHIRT!

ONLY

$100

PER

WEEK!

JOIN OUR CREW, BRING YOUR FRIENDS, MAKE NEW ONES, GET FIT, AND LEARN SOMETHING NEW!

WHAT TO EXPECT

Whoa! I have no idea what we’re getting into! Hopefully, this will help you out. Most folks have no idea what crew is. Their exposure to the sport may amount to a few minutes during an Olympic broadcast at most. Or they might have seen us on the canal paddling the long canoes. Every rower on the team has started off right where you are! Here’s a little about what you can expect at camp.

Every rower on the team has started off right where you are! Here’s a little about what you can expect at camp.

Rowing is a full-body, physical sport. It involves all the major muscle groups and a good bit of mental focus. That doesn’t mean that you need to be in top physical shape, but you must be capable of physical activity. You should be a competent swimmer. While it’s unlikely that you will end up in the water, this is a water sport. You should be able to float, tread water, and swim short distances. And you should have the desire to learn something brand new. Pre-existing conditions like asthma, etc. are not disqualifiers. So long as the new rower is cleared for physical activity, you can participate!

Our boathouse is at the Atlantic Yacht Basin, 2615 Basin Rd, in Chesapeake, right near the Great Bridge drawbridge. When you come to AYB, please park on the grass along the road or on the fire road. Do not park on AYB’s paved lot. There will be a Hickory Crew tent right there and folks to guide you. We row on the Albemarle & Chesapeake Canal.

We row on the Albemarle & Chesapeake Canal.

On arrival at the facility, we’ll check you in, answer any lingering questions, make sure the paperwork is all in, then escort you down to the boathouse. Parents are welcome to tag along.

We’ll give you a short tour of the facilities, show you the boats, and introduce you to the tools of our sport. Then we’ll start everyone on our rowing machines, called ergometers. The ‘erg’ provides a stable platform for teaching new rowers the sequence of body movements for the rowing stroke without the worry of being in a boat that rocks from side to side. As rowing requires asynchronous motion between everyone in the boat, this is an important element to grasp. This will encompass days 1 & 2. Towards the end of day 2, we’ll put the new rowers into what we call the ‘row box’. It’s a training device that is a section from a boat that we use to teach oar handling skills.

Our goal is to start getting people on the water on day 3. We’ll be using our 8s (8 rowers in the boat), with a mixture of new rowers and our varsity team members. The remainder of your time at camp will (hopefully) be spent on the water. There’s a lot to come to grips within the boat, so we’ll start off slow with half the rowers ‘setting the boat’ (keeping it balanced) so that those rowing can get the idea of how it’s all put together on the water and rotate you frequently. As your skill and confidence grow on succeeding days, more rowers will row together.

We’ll be using our 8s (8 rowers in the boat), with a mixture of new rowers and our varsity team members. The remainder of your time at camp will (hopefully) be spent on the water. There’s a lot to come to grips within the boat, so we’ll start off slow with half the rowers ‘setting the boat’ (keeping it balanced) so that those rowing can get the idea of how it’s all put together on the water and rotate you frequently. As your skill and confidence grow on succeeding days, more rowers will row together.

When boats are on the water, we have coaches in motor launches out with them to coach them and ensure safety. They are in contact with the practice parents onshore and have marine radios to communicate with boaters if need be.

CLOTHING

WHAT TO WEAR

Athletic attire. Should be snug, but not restrictive. Baggy shorts are not advised as the rower sits on a sliding seat and the short will get caught up in the wheels. The wheels always win. Same with overly long shirts.

Lots of body movement, so make sure your clothing won’t get in the way. Athletic shoes. We don’t do a lot of running, but you will run down as part of your warm-up starting day 2. No sandals, no crocs, no flip-flops. Socks! Wet feet are a regular element of this sport, even if the boat is dry, the dock could be wet.

Lots of body movement, so make sure your clothing won’t get in the way. Athletic shoes. We don’t do a lot of running, but you will run down as part of your warm-up starting day 2. No sandals, no crocs, no flip-flops. Socks! Wet feet are a regular element of this sport, even if the boat is dry, the dock could be wet.

WEATHER

RAIN OR SHINE

We will still likely row if it’s just misting, sprinkling, or a light rain. Heavy downpours are an issue. As is lightning. If it looks like it’s just a quick passing event, we may wait it out in the boathouse. If it’s a bigger issue, we’ll likely pull the plug on that day’s activities. Regardless, we’re always watching the weather.

PROTECTION

IN THE ELEMENTS

We are outside in the elements. Hats, sunglasses, sunscreen, etc. are all advised. (The canal runs east-west. When you’re rowing to the east, the afternoon sun is full in your face.) Don’t bring expensive sunglasses as they could end up at the bottom of the canal. Bug spray if you’re susceptible.

Bug spray if you’re susceptible.

PHONES

AND PERSONAL ITEMS

Leave your phone and other valuables either in the boathouse, the car, or with a parent. Do not take them in the boat!

HYDRATE

BRING WATER

We’ll have some there for the first few days but bring water thereafter. Summer in Virginia, hot weather, and physical activity all lead to thirsty rowers. Proper hydration is imperative. Take it in the boat with you!

Please select from the options below:

I STILL HAVE QUESTIONS

FAQ’s:

Do I have to join the team afterward?

Attending camp does not mean that you must join the team. Of course, we want you to join the team, but rowing’s not for everyone. Or maybe your just curious and want to try something new. Or maybe it just sounds like fun. Come give it a try and see where it leads you!

What if I can only attend 1 week?

That’s fine. Doesn’t matter if it’s the first or the second week. The training sequence will be pretty much the same. If you can only come one week, $100.

The training sequence will be pretty much the same. If you can only come one week, $100.

Do I have to go to Hickory to attend?

Nope. You can be a student at any school or home-schooled to attend our camp. So long as you’re at least a rising 7th grader and haven’t graduated high school yet, you’re eligible. If you decide to join the team, there may be some eligibility issues depending upon what school you’ll be attending.

What time is the camp?

We start promptly at 5pm and finish at 7pm. We ask that you are on time, or a little early as once we are out on the water we will not be back to the shed or dock until the end of the session and you may literally “miss the boat.”

How much does it cost?

$200 for the 2-week session. If you do decide to join the team, your dues will be discounted by your camp fee.

Do I have to be there every day?

No, but rowing is a sport that responds very well to repetition. If you’re only going to miss a day or 2, not a big deal.

If you’re only going to miss a day or 2, not a big deal.

Learn To Row | Juniper Rowing Club

Our Learn-to-Row program takes place in two four-hour sessions on Saturday and Sunday mornings. Saturday consists of about 2 hours of shore training and 2 hours of actual rowing, and Sunday includes two 2-hour sessions on the water with a break and video feedback. Both sweep rowing (one long oar) and sculling (two shorter oars) will be introduced, with the focus and in-boat rowing type determined by class size. All LTR participants will be given an opportunity to experience both types of rowing, on a follow-up basis during the season. Learn-To-Row sessions cost only $100 for the two day class and the New Rower Program, with prorated club membership options thereafter.

Learn-To-Row Sessions for 2023

- April 29th-30th

- May 20th-21st

- June 10th-11th

- While not currently planned, additional 2023 dates are a possibility and would be announced here.

- LTR sessions take place at Atlantic Yacht Basin from 8am – 11 noon on Saturday and 8am – 10am on Sunday.

The Saturday morning session includes:

- Introduce new rowers to the club, the sport, and the equipment.

- Shown the basic rowing stroke, do’s and don’ts, and nuances.

- Learn boathandling (carrying shells) instructed and assisted by Juniper members.

- Meet the erg (rowing machine), and learn the correct stroke technique with individual coaching.

- Sit in shells secured to the dock, with oars, and learn the correct stroke, with up-close coaching.

- Get out in a shell with Junipers, for on-water rowing, accompanied by a coach in a launch.

The Sunday morning session includes:

- Getting on the water in two (2-hour) sessions, with cox feedback, and coached from a launch.

- Filmed on-water and later get to see the video and are critiqued (videos are later added to YouTube so they can review themselves)

Where we Meet:

We meet at the Atlantic Yacht Basin located at: 2615 Basin Rd, Chesapeake, VA 23322

Parking is on the right hand side of Basin Road in the grass or next to the gravel fire road; we do not park in the parking lot in front of the Atlantic Yacht Basin.

Time we Meet:

Please plan to arrive in the parking area by 7:45 a.m. so we can all walk down to the boathouse together.

Other Learn-to-Row Points:

- All LTR students must register and pay for the class in advance in order to participate, for planning purposes.

- If an LTR student has a conflict arise, cannot make their class, and advises the LTR Coordinator in advance, they may attend a subsequent LTR class.

- In the event of adverse weather, the LTR Coordinator will advise the LTR participants of the cancellation and will reschedule the class to accommodate the availability of, hopefully, all students.

If you have any questions about the Learn-to-Row program, Juniper Rowing Club in general, or would like to register for an upcoming session, please email our Learn-to-Row coordinator at [email protected].

Thanks, and as rowers say, “sit ready” (to row).

Like this:

Like Loading…

Philadelphia campaign

Philadelphia campaign (eng. Philadelphia campaign) – a combined campaign of the British army and navy during the American Revolutionary War, which lasted from the spring of 1777 to the spring of 1778. The target of the British army was the city of Philadelphia, where the Continental Congress met. British General William Howe attempted to draw George Washington’s army into battle in northern New Jersey, but failed. Then he loaded the army on transports and landed on the shores of the Chesapeake Bay and began to advance on Philadelphia from the south. Washington stationed an army at the turn of the Brandywine Creek, but on September 11, 1777, Howe outflanked his flank and Washington was defeated at the Battle of Brandywine. After another series of maneuvers and skirmishes, the British entered Philadelphia. Part of the British army camped near Germantown; Washington learned of this and attacked them, but he failed to win the Battle of Germantown on December 4.

Philadelphia campaign) – a combined campaign of the British army and navy during the American Revolutionary War, which lasted from the spring of 1777 to the spring of 1778. The target of the British army was the city of Philadelphia, where the Continental Congress met. British General William Howe attempted to draw George Washington’s army into battle in northern New Jersey, but failed. Then he loaded the army on transports and landed on the shores of the Chesapeake Bay and began to advance on Philadelphia from the south. Washington stationed an army at the turn of the Brandywine Creek, but on September 11, 1777, Howe outflanked his flank and Washington was defeated at the Battle of Brandywine. After another series of maneuvers and skirmishes, the British entered Philadelphia. Part of the British army camped near Germantown; Washington learned of this and attacked them, but he failed to win the Battle of Germantown on December 4.

The American army wintered at Camp Valley Forge, where poor supplies caused many to die of exhaustion. In the spring, a Prussian officer, Baron von Steuben, joined the army and developed a training system based on the practice of the Prussian army.

In the spring, a Prussian officer, Baron von Steuben, joined the army and developed a training system based on the practice of the Prussian army.

Howe managed to occupy Philadelphia, but because of this he was unable to support John Burgoyne’s army, which was marching towards New York from the north. Because of this, Burgoyne was defeated at the Battle of Saratoga. The defeat of Burgoyne led to the fact that France recognized the United States and entered into a military alliance with him against Great Britain. This threatened British possessions in the Caribbean and India, so in the spring of 1778 the government ordered General Howe to leave Philadelphia and confine himself to the defense of New York. Howe had resigned by this time, and General Henry Clinton took command, who organized the evacuation of Philadelphia. He began to retreat towards New York; Washington caught up with him near Monmouth, and on June 28 the Battle of Monmouth began, one of the largest battles of the war. It ended in a draw, but the battlefield was left to the Americans. Clinton retreated to New York, and Washington again took up positions near New York, as at the beginning of the campaign. The battles of the Philadelphia campaign were the last battles of that war in the territory of the northern states.

It ended in a draw, but the battlefield was left to the Americans. Clinton retreated to New York, and Washington again took up positions near New York, as at the beginning of the campaign. The battles of the Philadelphia campaign were the last battles of that war in the territory of the northern states.

Background

After the victory in the Battle of Long Island and the surrender of New York, the British army occupied almost the entire state of New Jersey, but in the winter, after the counteroffensive of Washington and the battles of Trenton and Princeton, they had to leave a large part of the state. Therefore, in 1777, General Howe decided to renew his efforts to destroy the Continental Army and suppress the resistance of the colonies, by an attack on Philadelphia, the seat of the Continental Congress, the city that, according to European ideas, is closest to the unofficial capital of the 13 colonies.

But at the same time, London approved General Burgoyne’s plan to advance from the north down the Hudson to cut the colonies in two. Accordingly, General Howe was expected to assist towards Burgoyne’s army. Thus a fatal disarray was introduced into grand strategy in America. In fact, Howe had neither the strength nor the time to pursue both goals.

Accordingly, General Howe was expected to assist towards Burgoyne’s army. Thus a fatal disarray was introduced into grand strategy in America. In fact, Howe had neither the strength nor the time to pursue both goals.

Preparations and plans

After the Battle of Princeton, the campaign of 1776 ended and Washington withdrew the army to the winter camp at Morristown. This position was advantageous in terms of defense, although not as convenient for living as the previous camp near Boston. General Howe remained with the army in New York, where he began planning for the 1777 campaign. His original plan, drawn up back in November, called for a three-pronged offensive: one army would advance on Boston, a second would advance up the Hudson to Albany, and a third, Canadian, army would advance on Albany from the north. By September or October the resistance in the north was supposed to be crushed, the army moved south, and the war ended by Christmas. In December, Howe suddenly changed plans: now he decided to advance on Philadelphia. This new plan arrived in London for approval just as the king had already agreed to the forefront and ordered John Burgoyne’s Canadian army to advance on Albany. And although the second plan contradicted the first, Lord Jermaine approved it.

This new plan arrived in London for approval just as the king had already agreed to the forefront and ordered John Burgoyne’s Canadian army to advance on Albany. And although the second plan contradicted the first, Lord Jermaine approved it.

In mid-January 1777, Howe drew up another plan: he asked for his army to be doubled by sending another 20,000 men so that he could attack Philadelphia from the sea at the same time. At the same time, he proposed to place a large detachment in Rhode Island for sabotage in Connecticut and Massachusetts. At that time in London, no one asked why it was necessary to attack Philadelphia, and to this day it is not known exactly what Howe was guided by in this decision. Perhaps he thought that the terrain of eastern Pennsylvania was more favorable for military operations than New Jersey and the New York area. He must have known that there were fewer militias in Pennsylvania than in New England. It is not known what benefit he saw in the capture of Philadelphia: even such a non-military man as John Adams wrote that by capturing the city, Howe would be in the worst possible situation. He made this decision immediately after the battles of Trenton and Princeton, when he became less confident in the success of the war, and when he first reported to London that he did not believe that the war could be completed in one campaign.

He made this decision immediately after the battles of Trenton and Princeton, when he became less confident in the success of the war, and when he first reported to London that he did not believe that the war could be completed in one campaign.

To counter the enemy, Washington needed an army. In 1775-1776 the army consisted of patriotic volunteers who believed that they could easily defeat professional soldiers. This army was defeated near New York, its soldiers went home and never returned. In September 1776, Congress decided to reorganize the army with 88 regiments. This time, the lowest strata of the population joined the army: landless, unemployed, free blacks, slaves and contract slaves. But recruitment into the army was slow, and there was no certainty that the army could be formed at all. By the beginning of summer, instead of the planned 75,000 people, only 9 were recruited000. There were problems with the officers. The situation with weapons improved slightly: 200 guns, 25,000 muskets, as well as stocks of gunpowder and flint were sent from France.

On March 26, the British attacked an American post and warehouse in the village of Peekskill on the Hudson, destroying many valuable supplies. Washington feared that they would repeat their attacks on the Hudson posts, but there were no repeats. Instead, in April 1777, they landed a force in Connecticut, which led to the Battle of Ridgefield and the death of General Wooster. But that same April, General Howe again changed his plans, withdrew all detachments from Connecticut and New Jersey, and concentrated on the plan to capture Philadelphia. His leadership in London did not coordinate his plans with those of the Canadian army in any way, and he himself did almost nothing in this direction, only suggested that Burgoyne capture Fort Ticonderoga and the city of Albany. After approving the final plan, Lord Jermain suggested to General Howe that he send raiding parties to Massachusetts and New Hampshire, and the King expressed the hope that Howe would coordinate his plans with those of the Canadian Army, but Howe ignored both recommendations.

Progress of the campaign

In mid-June 1777, Washington stood with an army at Middlebrook, closely watching the enemy army. On June 14, the British launched an offensive: Howe entered New Jersey and approached the village of Somerset Courthouse, which was located between Middlebrook and Princeton. At first, Washington decided that the Howe would go through Princeton to Philadelphia, but the British went without the means of crossing and, therefore, did not intend to cross the Delaware River. He decided that they wanted to lure his army out of Middlebrook Heights onto the plains, or they intended to attack Sullivan’s force on Delaware. Just in case, he ordered Sullivan to retreat to safety in Flemington. Reinforcements from the militias arrived in Washington and he even considered the possibilities of an attack, but the enemy was in a strong position, and on June 16 reinforced it with redoubts. On June 17, Howe sent his baggage trains to the rear, which could be interpreted as preparations for a swift offensive. June 18 passed uneventfully, and 19June Washington received a message that surprised him: Howe was retreating to Brunswick. Judging by the fact that as early as June 18, the British were building redoubts, the decision to retreat was made suddenly. Washington decided that Howe had retreated when he learned of the arrival of American reinforcements.

June 18 passed uneventfully, and 19June Washington received a message that surprised him: Howe was retreating to Brunswick. Judging by the fact that as early as June 18, the British were building redoubts, the decision to retreat was made suddenly. Washington decided that Howe had retreated when he learned of the arrival of American reinforcements.

Washington immediately ordered Nathaniel Greene’s division, Wayne’s brigade, and Daniel Morgan’s rifle detachment to attack the rear of Howe’s retreating army, but Howe retreated without loss across the Raritan River. Washington ordered his army to descend from the heights and move closer to the enemy, to Kibbletown, to act on the situation. Stirling’s detachment, numbering 2,500 people (Maxwell’s and Conway’s brigades), he sent to New Brunswick.

General Howe decided to take advantage of the situation and attack Stirling’s force in order to simultaneously cut off Washington’s escape route to Middlebrook. On June 26, two columns of the British army left Perth Emboy: Cornwallis’ column went to Woodbridge, and Vaughn’s column to Bonhampton. On June 26, the British met with Stirling’s detachment and the Battle of Short Hills took place. Stirling retreated with the loss of about 10 men killed, about 60 wounded and several guns. But Washington’s army managed to retreat to Middlebrook. Then Howe returned to Emboy, and from there to New York. His army was greatly discouraged by the senseless marches, and by the months of summer time that had passed without results.

On June 26, the British met with Stirling’s detachment and the Battle of Short Hills took place. Stirling retreated with the loss of about 10 men killed, about 60 wounded and several guns. But Washington’s army managed to retreat to Middlebrook. Then Howe returned to Emboy, and from there to New York. His army was greatly discouraged by the senseless marches, and by the months of summer time that had passed without results.

On July 3, Washington withdrew the army from Middlebrook to Morristown, from where they could quickly move to either Philadelphia or the Hudson River in the event of an advance of the Howe army to the north. The British army under Burgoyne was then advancing from Canada down the Hudson, but Washington was confident that Burgoyne could not take Fort Ticonderoga. But on July 10 a message came from General Skyler, written on June 7: Skyler wrote that General St. Clair had abandoned Ticonderoga and the fort must have been taken by Burgoyne. Howe’s attack on Philadelphia now seemed unlikely. On July 11, the Continental Army began to march north, and on the same day, reports of the fall of Fort Ticonderoga on July 6 were confirmed, although only two days later he learned that St. Clair’s army had survived. On July 22, Washington camped in Orange County and waited for more information about the armies of Burgoyne and Howe.

On July 11, the Continental Army began to march north, and on the same day, reports of the fall of Fort Ticonderoga on July 6 were confirmed, although only two days later he learned that St. Clair’s army had survived. On July 22, Washington camped in Orange County and waited for more information about the armies of Burgoyne and Howe.

On June 23, 1777, an armada of 267 pennants left New York and, from the point of view of American intelligence, disappeared for a month. Washington considered several possible targets for the expedition and could not choose which one to defend. Washington wrote:

…[the enemy] keeps our minds in a state of perpetual divination. If only we could guess their purpose. Their behavior is so mysterious that it is impossible to understand it in such a way as to draw a definite conclusion.

Original text (English) [the enemy] keep our imaginations constantly in the field of conjecture. I wish we could out fox on their object. Their conduct really is so mysterious that you cannot reason upon it so as to form any certain conclusion.

He repeatedly ordered the army to march either to Pennsylvania or back to New York, or ordered General Sullivan’s detachment to join him and defend Philadelphia, or return to New Jersey in the Hudson Valley. One officer of the 3rd Virginia Regiment remarked, “We did a full tour of Jersey.”

In August, Washington learned that the fleet was in the Chesapeake.

Occupation of Philadelphia

Initially, Howe intended to take the ships up the Delaware River, but the blockade squadron reported that the river was too densely lined with obstacles, and he shifted his direction west to the Chesapeake. After a nightmarish march in hot weather, calm and contrary winds, during which all the horses fell and disease struck a large part of the army, another exemplary landing was made at the top of the Chesapeake, at the mouth of the Elk River. But the long march completely destroyed the intended element of surprise.

Nevertheless, Howe managed to win at Brandywine on September 11 and then outmaneuver Washington. On September 25, he entered Philadelphia. Among the British trophies was the 24-gun continental frigate Delaware .

On September 25, he entered Philadelphia. Among the British trophies was the 24-gun continental frigate Delaware .

Cleanup of the Delaware River

Attack on Fort Red Bank, 1777

After this, the Continental Army switched to raid and waste tactics. So, on October 4, Washington, mindful of Trenton, again tried to take the Hessians by surprise. But Germantown did not turn out so well for him.

It fell to the Navy to open a route up the Delaware in order to drastically cut the army’s communications and give Admiral Howe’s fleet a safe anchorage.

The task was entrusted to the experienced commodore Hamond (eng. Andrew Snape Hamond), who had commanded the blockade squadron all the previous year. He got down to business in early October, starting with clearing the fairway through the barriers put up between Billing Island and the left bank (New Jersey). The coastal batteries, gunboats and row galleys of the Pennsylvania Navy resisted, but the overwhelming superiority of the Royal Navy soon showed.

However, he was not without setbacks. On October 22, the 64-gun ship HMS Augusta and the sloop HMS Merlin , supporting an unsuccessful Hessian attack against Fort Red Bank, ran aground on uncharted sandbanks. HMS Vigilant and bombardment ship Fury were too far away, on the other side of the island. The rest of the ships, including the flagship HMS Eagle , HMS Roebuck and the oldest HMS Somerset , 9 frigates0051 HMS Pearl and HMS Liverpool , kept downstream and did not dare to approach for support.

Despite frantic efforts to withdraw, on the morning of October 23, Augusta was still tightly aground, and attracted the concentrated fire of all American ships and batteries. She caught fire from the stern, and eventually exploded, and the explosion was “felt in Philadelphia like an earthquake.” The cause of the explosion was never determined, but the most popular theory was that bed nets were ignited by their own smoldering wads. Merlin was also abandoned and burned by the crew.

Merlin was also abandoned and burned by the crew.

It took a month of stubborn, mostly draw fights. The British took Fort Mifflin and in late October Fort Mercer. The “palisades” in the river were dismantled, which were blamed for the movement of the sandy shoals that killed Augusta and Merlin . And only after that the first freight transport reached Philadelphia. Most of the defending American ships were destroyed.

In exchange, the main British army was immobilized for two months, and the 1777 campaign effectively ended there. On December 5-8, Washington successfully repulsed Howe’s series of reconnaissance battles at the Battle of White Marsh. The British wintered in the relative comfort of the city, while Washington camped in the rugged valley of Valley Forge.

Spring Operations 1778

While wintering at Valley Forge, the Continental Army lost up to a quarter of its strength (2,500 men) to disease and frostbite. However, by the spring she retained discipline and was still combat-ready.

Meanwhile, the victory at Saratoga convinced the French government to enter the war. Thus, in 1778 the situation changed radically. General Howe resigned and returned to England, replaced by General Clinton.

Lord Carlisle’s commission, appointed to replace the Howe brothers, achieved nothing in the negotiations. The proposed deal: recognition of the independence of the colonies in exchange for agreeing to obey the foreign trade laws of England, was rejected by an emboldened Congress. The famous “Give me freedom or give me death” thus turned out to be just a slogan: political freedom without economic freedom is worth little.

On April 20, 1778, Washington sent a memorandum to his generals proposing three options for this spring. The first plan was to attack the British in Philadelphia. The second plan was to attack them in New York. The third plan was to stay put and build up strength. The generals sent their answers April 21-25. Anthony Wayne and John Patterson were in favor of attacking Philadelphia, while Lord Stirling suggested that Philadelphia and New York be attacked simultaneously. The majority voted for the second plan. He was supported by Henry Knox, Peter Mullenberg, Enoch Poor, Varnum, Maxwell and Green. The third option was mainly supported by the Europeans: Lafayette, Steuben and Duporteil. Steuben said that in some cases it is worth going all-in, but this is not the case. Washington was sure of the third option from the very beginning, and arranged a poll only to find out the mood of his generals. On May 8, he convened a general war council, which was attended in addition by Gates and Mifflin, but Wayne was absent. This time the generals spoke more cautiously and unanimously decided that it was preferable to stay in the camp and wait for the right moment.

The majority voted for the second plan. He was supported by Henry Knox, Peter Mullenberg, Enoch Poor, Varnum, Maxwell and Green. The third option was mainly supported by the Europeans: Lafayette, Steuben and Duporteil. Steuben said that in some cases it is worth going all-in, but this is not the case. Washington was sure of the third option from the very beginning, and arranged a poll only to find out the mood of his generals. On May 8, he convened a general war council, which was attended in addition by Gates and Mifflin, but Wayne was absent. This time the generals spoke more cautiously and unanimously decided that it was preferable to stay in the camp and wait for the right moment.

The news of the possible presence of the French in America forced Clinton to evacuate Philadelphia. Sent to scout, Lafayette narrowly escaped a British ambush at Barren Hill.

Battle of Monmouth

This time Clinton chose to march by land. In the course of it, Washington followed closely on the heels and on June 28 attacked the tail of the British column at Monmouth. The Battle of Monmouth ended in a draw, but another draw was more profitable for Washington than for the British. Those had concerns of a completely different order: the army and navy were needed to protect New York from the French.

The Battle of Monmouth ended in a draw, but another draw was more profitable for Washington than for the British. Those had concerns of a completely different order: the army and navy were needed to protect New York from the French.

Consequences

The Philadelphia campaign ended virtually in a draw. But this was due to events elsewhere: at Saratoga. Again, as in 1775 and 1776, Britain failed to end the war in the 1777 campaign. Once again, all the features that marked the conduct of this war by Britain were present: unclear and confused strategic leadership from London, underestimation of the enemy, subordination of sea power to land considerations, weak cooperation between army and navy. The desire to wage a colonial war by European methods also came out especially brightly. Thus, the belief that there was in America a certain center of gravity, like a capital, the mastery of which would give a decisive victory, led to an error in choosing the direction of the campaign, and as a result Burgoyne was left without support.

Lots of body movement, so make sure your clothing won’t get in the way. Athletic shoes. We don’t do a lot of running, but you will run down as part of your warm-up starting day 2. No sandals, no crocs, no flip-flops. Socks! Wet feet are a regular element of this sport, even if the boat is dry, the dock could be wet.

Lots of body movement, so make sure your clothing won’t get in the way. Athletic shoes. We don’t do a lot of running, but you will run down as part of your warm-up starting day 2. No sandals, no crocs, no flip-flops. Socks! Wet feet are a regular element of this sport, even if the boat is dry, the dock could be wet.