What are the main causes of burnout in athletes. How can athletic trainers identify signs of burnout. What strategies can be implemented to prevent athlete burnout.

The Pressure Cooker of Athletic Performance

Modern athletes face unprecedented demands on their time and energy. The traditional concept of an “off-season” has all but vanished, replaced by a relentless cycle of training, practice, and competition. This non-stop activity can create a perfect storm for burnout, especially among young athletes still developing their physical and mental resilience.

Consider the typical schedule of a collegiate athlete:

- 6-12 months of in-season competition and practice

- Year-round strength and conditioning programs

- Early morning workouts (sometimes as early as 5 AM)

- “Voluntary” skill development sessions

- Film study and tactical meetings

- Full academic course load

This grueling regimen leaves little time for rest, recovery, or pursuits outside of athletics. The constant pressure to perform and improve can create a state of chronic stress, setting the stage for burnout.

Defining Athlete Burnout: More Than Just Fatigue

Burnout in athletes goes beyond simple physical exhaustion. It’s a complex syndrome resulting from prolonged exposure to chronic stress without adequate recovery. Burnout typically develops in stages:

- Initial enthusiasm and high motivation

- Plateauing of performance despite increased effort

- Frustration and diminishing returns

- Apathy and loss of interest in the sport

- Physical and mental exhaustion

Many athletes experiencing burnout report feeling trapped by the circumstances of their sports participation. They may push through early warning signs due to external pressures or an internalized drive for success.

The Hidden Dangers of “More is Better”

The sports world often promotes a “more is better” mentality, glorifying athletes who push beyond their limits. This attitude, while sometimes inspiring, can have serious consequences when taken to extremes. Interestingly, professional sports leagues have recognized this danger, implementing mandatory rest periods through collective bargaining agreements.

Why is rest so crucial? The human body and mind require adequate recovery time to adapt to the stresses of training and competition. Without this recovery, performance plateaus or declines, and the risk of injury and burnout skyrockets.

The Paradox of Overtraining

Overtraining syndrome is closely linked to burnout. It occurs when an athlete undergoes a rigorous training regimen without sufficient recovery, leading to decreased performance and potential health issues. Paradoxically, the athlete’s attempts to improve through more training actually hinder their progress.

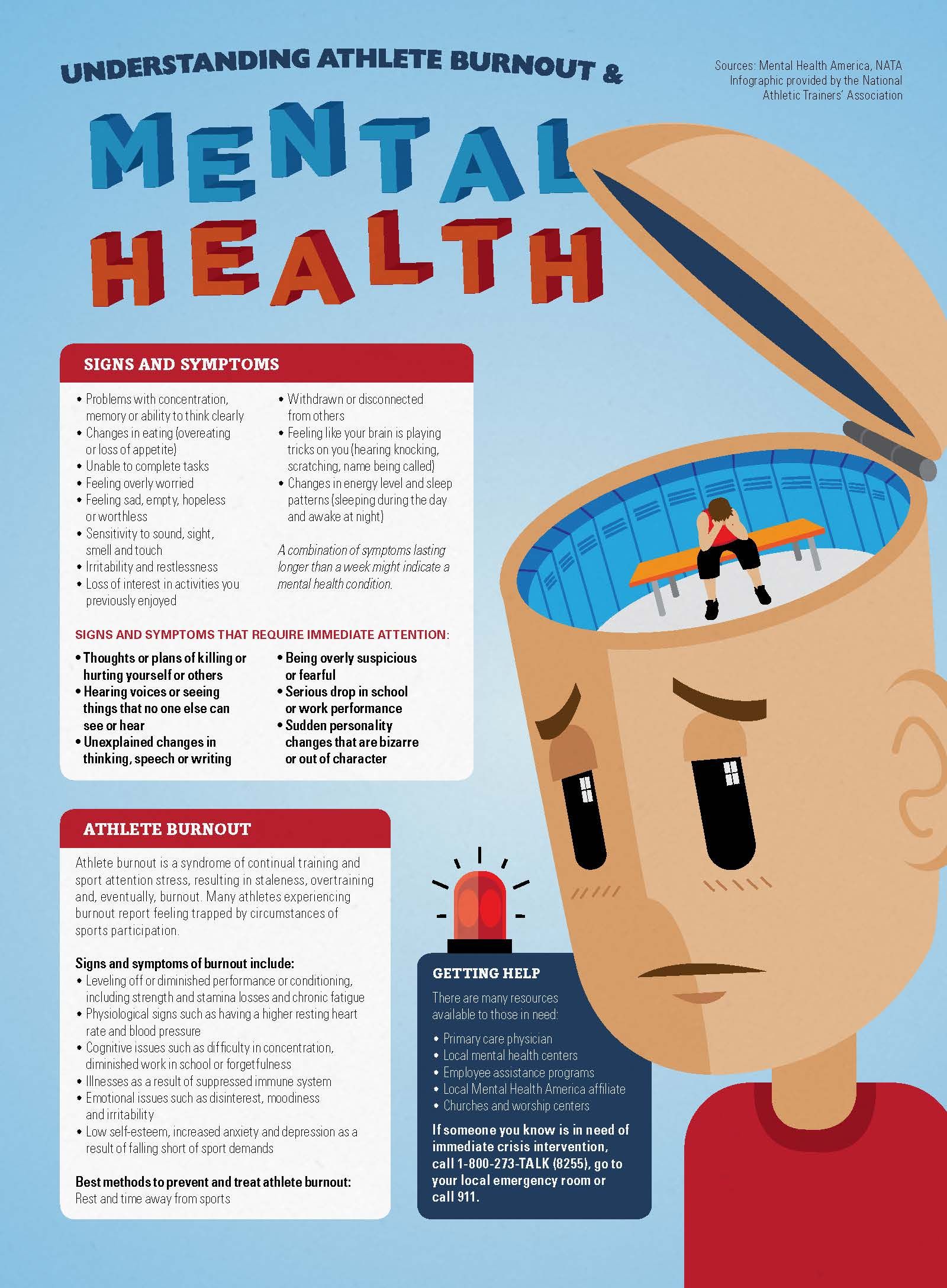

Recognizing the Signs and Symptoms of Athlete Burnout

Early identification of burnout is crucial for athlete well-being and performance. Athletic trainers, coaches, and support staff should be vigilant for the following signs:

Physical Symptoms

- Persistent fatigue and decreased energy levels

- Increased resting heart rate and blood pressure

- Frequent illnesses due to suppressed immune function

- Unexplained weight loss or changes in appetite

- Sleep disturbances

Performance-Related Symptoms

- Plateau or decline in performance metrics

- Decreased strength, stamina, and coordination

- Longer recovery times between training sessions

- Increased perceived effort during routine tasks

Psychological and Emotional Symptoms

- Loss of enthusiasm for the sport

- Irritability and mood swings

- Difficulty concentrating

- Feelings of depression or anxiety

- Lowered self-esteem

- Sense of detachment from teammates and coaches

It’s important to note that these symptoms can vary in severity and combination. Any persistent changes in an athlete’s physical or mental state warrant further investigation.

The Role of Athletic Trainers in Burnout Prevention

Athletic trainers are uniquely positioned to identify and address burnout in athletes. Their regular interactions with athletes during training and rehabilitation provide valuable opportunities for observation and intervention. Here are key strategies athletic trainers can employ:

Monitoring Workload and Recovery

Athletic trainers should work closely with coaching and strength staff to track athletes’ training volumes, intensities, and recovery periods. Implementing a system to monitor both external (e.g., distance run, weights lifted) and internal (e.g., perceived exertion, heart rate variability) loads can provide early warning signs of overtraining.

Education and Communication

Educating athletes, coaches, and parents about the signs and risks of burnout is crucial. Open communication channels allow athletes to express concerns without fear of judgment or repercussion. Regular check-ins on athletes’ physical and mental well-being should be part of the team’s routine.

Promoting a Balanced Approach

Athletic trainers can advocate for a more holistic approach to athlete development. This includes emphasizing the importance of rest, proper nutrition, and pursuits outside of sports. Encouraging athletes to maintain a life balance can help prevent the all-consuming nature of high-level sports participation.

Strategies for Preventing and Addressing Athlete Burnout

Preventing burnout requires a multi-faceted approach involving athletes, coaches, medical staff, and support networks. Here are key strategies to implement:

Periodization of Training

Structured training plans that incorporate periods of intensity and recovery can help prevent overtraining. This approach allows for peak performance during competition while minimizing the risk of burnout.

Mandatory Rest Periods

Implementing scheduled breaks throughout the year gives athletes time to physically and mentally recharge. This can include “no-contact” periods where organized team activities are prohibited.

Psychological Support

Access to sports psychologists or mental health professionals should be a standard part of athlete care. These experts can provide coping strategies and help athletes develop mental resilience.

Diversification of Activities

Encouraging athletes, especially younger ones, to participate in multiple sports or activities can prevent early specialization and reduce the risk of burnout.

Individualized Approaches

Recognizing that each athlete has unique physical and psychological needs is crucial. Training and recovery plans should be tailored to the individual, taking into account factors such as age, experience, and personal goals.

When Burnout Strikes: Intervention and Recovery

Despite best prevention efforts, some athletes will experience burnout. When this occurs, a structured intervention plan is essential:

Medical Evaluation

A thorough physical examination is the first step to rule out any underlying medical conditions that may be contributing to symptoms.

Psychological Assessment

A mental health professional can help determine the extent of burnout and develop a personalized recovery plan.

Temporary Reduction in Training Load

Depending on the severity of burnout, a period of complete rest or significantly reduced training may be necessary.

Gradual Return to Activity

As the athlete recovers, a carefully monitored return to training and competition should be implemented, with ongoing assessment of physical and mental well-being.

Long-Term Lifestyle Changes

Addressing the root causes of burnout often requires adjustments to the athlete’s overall approach to sports and life balance.

The Future of Athlete Burnout Prevention

As our understanding of athlete burnout evolves, so too must our approaches to prevention and treatment. Emerging areas of focus include:

Technology-Assisted Monitoring

Wearable devices and AI-powered analytics are providing unprecedented insights into athlete physiology and performance. These tools can help detect early signs of overtraining and burnout.

Holistic Athlete Development Programs

Progressive sports organizations are implementing comprehensive programs that address not only physical training but also mental health, nutrition, sleep quality, and life skills development.

Cultural Shift in Sports

There’s a growing recognition of the need to change the “win at all costs” mentality that often contributes to burnout. Promoting a culture that values athlete well-being alongside performance is crucial for long-term success.

Burnout in athletes is a complex issue that requires vigilance, education, and a collaborative approach from all stakeholders in the sports community. By implementing comprehensive prevention strategies and fostering a culture that prioritizes athlete well-being, we can help ensure that the pursuit of athletic excellence doesn’t come at the cost of physical and mental health.

As research in this field continues to advance, our understanding of athlete burnout and effective prevention strategies will undoubtedly evolve. The key is to remain adaptable, prioritize athlete welfare, and continually strive for a balance between performance demands and overall well-being. By doing so, we can create an environment where athletes can thrive both on and off the field, reaching their full potential while maintaining their passion for sport.

Burnout in Athletes | NATA

Editor’s note: This column kicks off a series of mental health-related columns that will be posted on the NATA Now blog throughout May in honor of Mental Health Awareness Month.

ByTimothy Neal, MS, ATC, LAT

Assistant Professor/Clinical Education Coordinator

Concordia University Ann Arbor

The pressure of being a successful athlete entails non-stop activity of games, practice and physical conditioning.

Games and practice have traditional and non-traditional seasons, usually encompassing six or more months of the year. For many athletes, summers are spent on campus working out or practicing. Conditioning sessions that are physically taxing can take place as early as 5 a.m. to accommodate class or work schedules. Additional “voluntary” sessions of physical conditioning, film study, or skill development, along with the rigors of school work, the modern athlete is on “overload” as a result of participation demands from the moment they step on campus until they leave school. This can create, for the athlete, a condition of chronic stress physically and, more importantly, mentally.

This can create, for the athlete, a condition of chronic stress physically and, more importantly, mentally.

The attitude of “more is better” in terms of constant activity in a quest for individual or team success is prevalent in today’s sports world, starting at the youth level and continuing through the secondary school and collegiate levels. Interestingly, professional sports have in place, through their collective bargaining agreements, mandated time off for the athletes to recover from the rigors of their season.

Burnout is a response to chronic stress of continued demands in a sport or activity without the opportunity for physical and mental rest and recovery. Burnout is a syndrome of continual training and sport attention stress, resulting in staleness, overtraining and eventually burnout. Many athletes experiencing burnout report feeling trapped by circumstances of sports participation. The athlete first starts feels stale or overwhelmed, but is encouraged by coaches, strength staff, athletic trainers, teammates or parents to push through symptoms of overtraining and potential burnout to continue with a demanding schedule in order to feel a part of the team, maintain their starting position or keep their scholarship.

Other athletes self-induce their burnout with personal motivation for success. This type of athlete applies more personal demands on their physical conditioning and skill sessions, or is fully consumed by sports participation as a way to fulfill their identity as an athlete. Either way, the chronic stress the athlete experiences without the opportunity to rest and recover from the rigors of such stress places the athlete at risk for burnout. For some athletes, burnout may be the triggering mechanism in developing or exacerbating a mental health disorder that negatively impacts the athlete’s life and relationships.

Burnout affects the athlete in various stages:

- The athlete is placed in a situation that involves new or varying demands on their physical ability and time management

- The athlete at some point – usually early on as a young athlete, or later if a more experienced athlete – views the demands as excessive or non-productive

- The athlete feels as if their performance is being hampered by the demands of participation and the inability to rest and recover

- The athlete starts experiencing subtle signs and symptoms of physical and mental burnout

- Burnout takes place and the physical and mental toll on the athlete impacts their lives and performance on and off the field, perhaps even discontinuing sports participation

Signs and symptoms of burnout include:

- Leveling off or diminished performance or conditioning, including strength and stamina losses, chronic fatigue

- Physiological signs such as having a higher resting heart rate and blood pressure

- Cognitive issues such as difficulty in concentration or diminished work in school, forgetfulness

- Illnesses as a result of suppressed immune system

- Emotional issues such as disinterest, moodiness, irritability

- Low self-esteem, increased anxiety and depression as a result of falling short of sport demands

Athletic trainers can help in identifying and preventing burnout in athletes through an awareness of the signs and symptoms, and in communication with coaches and strength staff to monitor the athletes for overtraining, which is a large contributor of burnout. Whenever an athlete, particularly a younger athlete new to the level of participation, exhibits some signs and symptoms of burnout, a physician evaluation for a physical cause is warranted. After the physician exam and any testing prove negative, consideration should be given to modifying the activity to permit more athlete rest and recovery. If physical causes for signs and symptoms of burnout are negative, consideration should be given to referring the athlete for a psychological evaluation and care.

Whenever an athlete, particularly a younger athlete new to the level of participation, exhibits some signs and symptoms of burnout, a physician evaluation for a physical cause is warranted. After the physician exam and any testing prove negative, consideration should be given to modifying the activity to permit more athlete rest and recovery. If physical causes for signs and symptoms of burnout are negative, consideration should be given to referring the athlete for a psychological evaluation and care.

Coaches and strength staff should be educated on burnout and consider modifications to workouts both in terms of intensity and length of time in order to preserve optimal levels of performance and to prevent burnout. Some measures such as heart-rate monitoring during practice and conditioning are one of several approaches teams are utilizing to monitor potential overtraining.

Rest and time away from sport are the two best methods to prevent and treat athlete burnout. Athletes, like most students and American adults, do not get enough sleep to feel rested and ready for physical and mental activity throughout the day. Seven to eight hours of sleep are recommended daily. Considering that many athletes rise before or at dawn for conditioning sessions and practice, their sleep cycle is hampered to be fully effective in providing the rest necessary for daily activities and optimal school and sports performance. This results in a state of constant fatigue, placing the athlete at risk for developing burnout and mental health issues, especially when the athlete feels there is no escaping the time and physical demands of their sport and school.

Seven to eight hours of sleep are recommended daily. Considering that many athletes rise before or at dawn for conditioning sessions and practice, their sleep cycle is hampered to be fully effective in providing the rest necessary for daily activities and optimal school and sports performance. This results in a state of constant fatigue, placing the athlete at risk for developing burnout and mental health issues, especially when the athlete feels there is no escaping the time and physical demands of their sport and school.

Time away from sport is another method of preventing burnout. Being away from the demands of their sport, even for a short period several times a year, provides an athlete with an opportunity to attend to their schoolwork and relationships that are necessary to leading a more rounded life that leads to enhanced motivation once they return to sport.

Burnout is a very real and underreported state that many athletes experience. Knowing the signs and symptoms of escalating burnout, along with an appreciation how burnout occurs, are important steps in prevention and treatment of this situation, and may well prevent the start or worsening of a mental health disorder in an athlete.

To help you educate parents, athletes, coaches and others about burnout, NATA has created a burnout and mental health handout (pdf), which was featured in the May NATA News.

Don’t forget to check out our other infographic handouts that have been made available for NATA members to download, reprint and distribute to their local communities.

How to Avoid Athlete Burnout in Youth Sports

The increasingly competitive nature of youth sports can result in athlete burnout. Previously associated with adults who are exhausted and disillusioned with their jobs, burnout has now spread from offices to youth sports courts, fields, and rinks everywhere.

Ongoing work by researchers like East Carolina University’s Dr. Thomas D. Raedeke is revealing not only the real causes of burnout in youth athletes, but also how it can be prevented.

Why Youth Athletes Experience Burnout

Burnout is in part a reaction to chronic stress. According to Dr. Raedeke, the stress can come from overtraining but also from external sources. It can directly stem from parents who pressure their child, or more subtly from family life that evolves around sport. It can also result from negative coaching behaviors. Some athletes also have internal personality characteristics, like an innate sense of perfectionism, that make them vulnerable to burnout. But stress is only part of the story.

According to Dr. Raedeke, the stress can come from overtraining but also from external sources. It can directly stem from parents who pressure their child, or more subtly from family life that evolves around sport. It can also result from negative coaching behaviors. Some athletes also have internal personality characteristics, like an innate sense of perfectionism, that make them vulnerable to burnout. But stress is only part of the story.

“Not only might burnout-prone athletes begin to realize sports success is not as meaningful as they once thought, the athletes might also believe success ultimately is not possible because skill improvements are inevitably linked to increased expectation and standards,” says Dr. Raedeke.

“As a result, they may realize they can never be good enough and that they are chasing an impossible goal.”

A lack of independence or feeling like they have no say in the matter can also play a role.

Signs of Athlete Burnout

The signs of athlete burnout are not always obvious, and they can overlap with other kinds of stress, such as overtraining or life and school pressures. Research suggests sports burnout runs deeper and presents with three major symptoms:

Research suggests sports burnout runs deeper and presents with three major symptoms:

- Emotional and physical exhaustion: Chronic fatigue from constant physical and psychological demands connected to intense training and competition

- Devaluation and detachment: A negative or cynical attitude toward sports and disinterest in performance

- Reduced sense of accomplishment: Negative perspective on performances and accomplishments

Raedeke also thinks that these signs can interact. For example, feeling less accomplished could prompt athletes to train harder, leading to exhaustion. Feeling exhausted could cause athletes to develop a sense of detachment and ultimately quite sports.

Unfortunately, the cycle doesn’t end there either. Burnout can also negatively impact other areas of the athlete’s life and it has specifically been linked to lowered mental and physical health outside of sport.

How Coaches and Parents Can Help Douse Burnout

Like an actual fire, burnout is best handled through prevention instead of reaction. Raedeke states that “burnout is a relatively chronic state,” meaning there are no proven treatments for curing burnout. It can, however, be prevented.

Raedeke states that “burnout is a relatively chronic state,” meaning there are no proven treatments for curing burnout. It can, however, be prevented.

Managing the following factors can help athletes deal with burnout:

- Balance training demands with recovery: As Raedeke notes from his research in Burnout in Sport: From Theory to Intervention, “It is not possible for an athlete to ‘train through’ a long-lasting performance slump caused by excessive training and inadequate recovery.”

When planning for the season, be sure to add ‘off-cycle’ weeks to your athlete’s training program to promote optimal adaptation to training demands.

- Promote balance: Take steps to make sure that an athlete isn’t overinvolved in sport to the point where they are missing out on other life opportunities. For example, encourage your athletes to spend time with friends outside of a sports setting.

Create a space where young athletes have unstructured free time and are allowed to participate in or explore other interests.

- Have a positive support network: Foster a more positive environment for your athletes.

Recent research of college athletes shows that even just the feeling of having a positive support network from teammates resulted in less burnout and more motivation.

- Empower athletes: Structure sport in a way that allows athletes to have some input and collaborate on decisions related to participation.

___

In the end, preventing burnout comes down to keeping sports fun, decreasing stress, and reducing the chance that an athlete will feel trapped by sport.

Burnout in Sport and Performance

Introduction

Burnout among athletes as a consequence of the stress of highly competitive sport became a concern following the emergence of commentaries on troubling chronic experiential states experienced by some professionals in stressful alternative health care (e. g., Freudenberger, 1974, 1975) and human service settings (e.g., Maslach, 1982). Freudenberger’s observations on a phenomenon involving physical and mental deterioration and workplace ineffectiveness as a consequence of excessive demands among alternative health care professionals are typically regarded as formally ushering the term “burnout” into the psychosocial lexicon (Eklund & Cresswell, 2007). Maslach (1982) observed a similar phenomenon in studying human service workers. Her development of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI; Maslach & Jackson, 1981, 1986) to study the phenomenon effectively served to conceptually formalize burnout as an experiential syndrome involving symptoms of sustained feelings of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization (negative attitudes and feelings toward the recipients of the service), and inadequate personal accomplishment (a sense of low accomplishment and professional inadequacy). Following the emergence of these insights and developments in work settings, “burnout” in sport quickly became an amorphous catch-all explanation for an array of troubling phenomena, including the negative, amotivated, and exhausted states sometimes suffered by athletes as well as implicated problems with injury, sport withdrawal, and/or personal dysfunction.

g., Freudenberger, 1974, 1975) and human service settings (e.g., Maslach, 1982). Freudenberger’s observations on a phenomenon involving physical and mental deterioration and workplace ineffectiveness as a consequence of excessive demands among alternative health care professionals are typically regarded as formally ushering the term “burnout” into the psychosocial lexicon (Eklund & Cresswell, 2007). Maslach (1982) observed a similar phenomenon in studying human service workers. Her development of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI; Maslach & Jackson, 1981, 1986) to study the phenomenon effectively served to conceptually formalize burnout as an experiential syndrome involving symptoms of sustained feelings of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization (negative attitudes and feelings toward the recipients of the service), and inadequate personal accomplishment (a sense of low accomplishment and professional inadequacy). Following the emergence of these insights and developments in work settings, “burnout” in sport quickly became an amorphous catch-all explanation for an array of troubling phenomena, including the negative, amotivated, and exhausted states sometimes suffered by athletes as well as implicated problems with injury, sport withdrawal, and/or personal dysfunction. Efforts to conceptualize and understand athlete burnout started appearing in the sport science literature soon thereafter (e.g., Cohn, 1990; Feigley, 1984; Gould, 1993; Henschen, 1990; Rowland, 1986; Schmidt & Stein, 1991; Smith, 1986; Yukelson, 1990).

Efforts to conceptualize and understand athlete burnout started appearing in the sport science literature soon thereafter (e.g., Cohn, 1990; Feigley, 1984; Gould, 1993; Henschen, 1990; Rowland, 1986; Schmidt & Stein, 1991; Smith, 1986; Yukelson, 1990).

While the notion of burnout held considerable appeal for sport scientists, reservations existed about the relevance and applicability of Maslach and Jackson’s (1981, 1986) burnout syndrome to athletes (e.g., Feigley, 1984; Garden, 1987). The stresses and circumstances of athletes’ involvement in sport are much different from those of professionals involved in health and human service settings, so it seemed entirely reasonable to question “the extent to which the nature, causes and consequences are unique and to what extent they are shared by those who suffer burnout in other domains of activity” (Smith, 1986, p. 44). Nonetheless, variation in the nature of ongoing stressful demands does not inherently require that the associated experiential consequences also differ in their aversive nature. Evidence across a variety of workplace settings has indicated that there is commonality in the experience of burnout in response to chronic situational exposure to psychosocial stress, despite variation in the specific stressors implicated across workplace settings (Schaufeli & Enzmann, 1998). Evidence from studies with athletes involved in serious competitive sport have also supported Schaufeli and Enzmann’s conclusions about cross-domain (i.e., sport versus work) commonality in the experience of burnout as a response to chronic exposure to psychosocial stress (Eklund & Cresswell, 2007; Goodger, Gorely, Lavallee, & Harwood, 2007).

Evidence across a variety of workplace settings has indicated that there is commonality in the experience of burnout in response to chronic situational exposure to psychosocial stress, despite variation in the specific stressors implicated across workplace settings (Schaufeli & Enzmann, 1998). Evidence from studies with athletes involved in serious competitive sport have also supported Schaufeli and Enzmann’s conclusions about cross-domain (i.e., sport versus work) commonality in the experience of burnout as a response to chronic exposure to psychosocial stress (Eklund & Cresswell, 2007; Goodger, Gorely, Lavallee, & Harwood, 2007).

The athlete burnout syndrome as conceptualized by Raedeke (1997), Raedeke and Smith (2001) is characterized by the enduring experience of (1) emotional and physical exhaustion, (2) sport devaluation, and (3) reduced accomplishment. Although modified to be of particular relevance to sport, this sport-specific conceptualization of the syndrome is consistent with the syndrome posited by Maslach and Jackson (1981, 1986). Specifically, the general notion of a sense of inadequate or reduced personal accomplishment being symptomatic of burnout mapped over directly in Raedeke’s conceptualization. Maslach and Jackson’s (1981, 1986) emotional exhaustion syndrome facet was extended to include chronic physical exhaustion. This modification was consistent with the broadening of the exhaustion construct in the third edition of the MBI manual with the introduction of the MBI General Survey (Maslach, Jackson, & Leiter, 1996). The original depersonalization syndrome facet was argued to have little sport-specific relevance because client services do not feature in athletes’ experiences per se, so it was replaced with a facet relating to sport devaluation (a cynical and diminished appraisal of the benefits of sport involvement by the athlete). This change was also consistent with the re-conceptualization of depersonalization in the general workplace literature as a particular manifestation of the cynicism that occurs in burnout (e.

Specifically, the general notion of a sense of inadequate or reduced personal accomplishment being symptomatic of burnout mapped over directly in Raedeke’s conceptualization. Maslach and Jackson’s (1981, 1986) emotional exhaustion syndrome facet was extended to include chronic physical exhaustion. This modification was consistent with the broadening of the exhaustion construct in the third edition of the MBI manual with the introduction of the MBI General Survey (Maslach, Jackson, & Leiter, 1996). The original depersonalization syndrome facet was argued to have little sport-specific relevance because client services do not feature in athletes’ experiences per se, so it was replaced with a facet relating to sport devaluation (a cynical and diminished appraisal of the benefits of sport involvement by the athlete). This change was also consistent with the re-conceptualization of depersonalization in the general workplace literature as a particular manifestation of the cynicism that occurs in burnout (e. g., Maslach et al., 1996; Maslach, Schaufeli, & Leiter, 2001). Overall, the emergence and subsequent broad acceptance of this syndrome conceptualization of athlete burnout resulted in commentaries that took on more conceptual coherence. Empirical investigations of this commonly accepted athlete burnout conceptualization also served to advance theoretical understanding of the problematic condition.

g., Maslach et al., 1996; Maslach, Schaufeli, & Leiter, 2001). Overall, the emergence and subsequent broad acceptance of this syndrome conceptualization of athlete burnout resulted in commentaries that took on more conceptual coherence. Empirical investigations of this commonly accepted athlete burnout conceptualization also served to advance theoretical understanding of the problematic condition.

The emergence of Raedeke’s (1997), Raedeke and Smith (2001) syndrome conceptualization was also particularly important because, before that time, discussions of athlete burnout were not necessarily all focused on the same construct. The commentaries instead spanned a variety of distinct, if interrelated, constructs, including reference to depressed mood states, amotivation, maladaptive psychophysiological responses to training, sport dropout, and so on (Eklund & Cresswell, 2007). The “everybody knows what it is” problem (Marsh, 1998, p. xvi) was evident in the variety of idiomatic and amorphous conceptualizations being discussed because the commentaries were often grounded in anecdotal accounts provided by coaches, sport scientists, and even athletes themselves (Dale & Weinberg, 1990; Rotella, Hanson, & Coop, 1991). The net effect was that early research and theoretical development efforts were focused on an array of constructs all sharing the label of “athlete burnout” rather than a single common experience.

The net effect was that early research and theoretical development efforts were focused on an array of constructs all sharing the label of “athlete burnout” rather than a single common experience.

The noticeably different conceptualizations of athlete burnout employed by Silva (1990) and Coakley (1992) are illustrative of the problem identified in the preceding paragraph. Silva conceptualized athlete burnout as the ultimate phase in a maladaptive response to overtraining. The burnout phase, though sharing some commonalities with the burnout syndrome conceptualization, was posited to become manifest when “[t]he organism’s ability to deal with the psychophysiological imposition of stress is depleted, and the response system is exhausted” (p. 11). Silva’s (1990) perspective effectively conflates the burnout syndrome with the overtraining (or staleness) syndrome (Eklund & Cresswell, 2007). Some commonalities are evident across the two chronic conditions (e.g., exhaustion, mood disturbances, concerns about performance adequacy), but they should be regarded as distinct conditions requiring nonidentical intervention strategies (Raglin, 1993). At its core, the overtraining syndrome is a chronic condition involving systemic (e.g., neurological, endocrinological, and immunological) maladaptive responses to excessive overreach training (Kreher & Schwartz, 2012). The athlete burnout syndrome, however, results from chronic exposure to psychosocial stress and, importantly, can become manifest entirely in the absence of excessive overreach training (Eklund & Cresswell, 2007). Coakley’s (1992) conceptualization of athlete burnout, however, is considerably different. He regarded athlete burnout as being withdrawal (i.e., dropout) from committed, successful involvement in highly competitive youth sport to escape its controlling and aversive socioenvironmental constraints. His perspective stands in stark contrast with other extant athlete burnout conceptualizations (e.g., Raedeke, 1997; Silva, 1990; Smith, 1986) wherein withdrawal from sport is viewed not as burnout in and of itself but rather as one potential, but not requisite, consequence of the burnout experience.

At its core, the overtraining syndrome is a chronic condition involving systemic (e.g., neurological, endocrinological, and immunological) maladaptive responses to excessive overreach training (Kreher & Schwartz, 2012). The athlete burnout syndrome, however, results from chronic exposure to psychosocial stress and, importantly, can become manifest entirely in the absence of excessive overreach training (Eklund & Cresswell, 2007). Coakley’s (1992) conceptualization of athlete burnout, however, is considerably different. He regarded athlete burnout as being withdrawal (i.e., dropout) from committed, successful involvement in highly competitive youth sport to escape its controlling and aversive socioenvironmental constraints. His perspective stands in stark contrast with other extant athlete burnout conceptualizations (e.g., Raedeke, 1997; Silva, 1990; Smith, 1986) wherein withdrawal from sport is viewed not as burnout in and of itself but rather as one potential, but not requisite, consequence of the burnout experience.

Given the existence of the variety of different conceptualizations employed in early athlete burnout research, some entangled with other related but distinct conditions (e.g., depression, overtraining syndrome, dropout), careful consideration is required in interpreting that literature relative to more contemporary syndrome-based efforts. Despite the conceptual challenges presented in some of the historical efforts, they were important to the field. They incited interest in the empirical investigation of burnout in sport and ultimately resulted in greater fidelity in construct conceptualization as well as the introduction of well-grounded theoretical explanations of the aversive experiential state (Eklund & Cresswell, 2007).

An early milestone in research on athlete burnout can be found in the International Tennis Federation’s implementation of rule changes and provision of educational recommendations to deal with the problem in the 1980s (Hume, 1985). Subsequent funding of a research project on athlete burnout by the United States Tennis Association Sport Science Division (e. g., Gould, Tuffey, Udry, & Loehr, 1996, 1997; Gould, Udry, Tuffey, & Loehr, 1996) served to catalyze the interest of sport psychology researchers in the topic. The absence of a conceptually and psychometrically sound measure of athlete burnout, however, presented an initial obstacle to research. The arrival of the Athlete Burnout Questionnaire (ABQ; Raedeke, 1997; Raedeke & Smith, 2001) resolved that problem, and subsequent research on the topic has burgeoned in quantity, and conceptual and methodological sophistication.

g., Gould, Tuffey, Udry, & Loehr, 1996, 1997; Gould, Udry, Tuffey, & Loehr, 1996) served to catalyze the interest of sport psychology researchers in the topic. The absence of a conceptually and psychometrically sound measure of athlete burnout, however, presented an initial obstacle to research. The arrival of the Athlete Burnout Questionnaire (ABQ; Raedeke, 1997; Raedeke & Smith, 2001) resolved that problem, and subsequent research on the topic has burgeoned in quantity, and conceptual and methodological sophistication.

Key Burnout Antecedents and Supporting Theories/Models

Ultimately, early anecdotal accounts and attempts to formulate theories on athlete burnout led to a core set of historical explanations for the sport-based phenomenon. Three early conceptualizations were especially influential; they specified that burnout was the result of (1) chronic exposure to psychological stress and maladaptive coping processes (Smith, 1986), (2) a maladaptive pattern of sport commitment (Raedeke, 1997), or (3) the autonomy-usurping constraints of intense involvement in highly competitive youth sport on young athletes’ identities and control beliefs (Coakley, 1992). Ultimately, all three conceptualizations have been useful in developing broad understandings of athlete burnout and key antecedents, despite the lack of definitional uniformity across instances. They continue to have relevance for investigative design and interpretation of burnout research. Consequently, we briefly review each conceptual perspective before outlining some general tenets of self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Ryan & Deci, 2000a, 2000b). Self-determination theory has subsequently become an influential theoretical perspective guiding athlete burnout research.

Ultimately, all three conceptualizations have been useful in developing broad understandings of athlete burnout and key antecedents, despite the lack of definitional uniformity across instances. They continue to have relevance for investigative design and interpretation of burnout research. Consequently, we briefly review each conceptual perspective before outlining some general tenets of self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Ryan & Deci, 2000a, 2000b). Self-determination theory has subsequently become an influential theoretical perspective guiding athlete burnout research.

Smith (1986) provided perhaps the earliest formal theorizing on athlete burnout as a psychosocial construct in the sport science literature. His conceptualization of burnout related to the “psychological, emotional, and at times a physical withdrawal from a formerly pursued and enjoyable activity” (p. 37). It relied on the work of several theoretical perspectives from psychology, including social exchange theory (Thibaut & Kelley, 1959) and Lazarus’s (1966, 1982) contentions on emotion and the stress and coping process./GettyImages-498071397-56a4717e5f9b58b7d0d6fd5e.jpg) In Smith’s view, athlete burnout was a result of chronic sport-related appraisals of stress that were not effectively mitigated by coping efforts. A variety of cross-sectional research studies have supported links between burnout and perceived stress and deficits in coping resources (e.g., Raedeke & Smith, 2001; 2004). More recently, Schellenberg, Gaudreau, and Crocker (2013) provided longitudinal evidence in a study of passionate involvement in sport supporting earlier cross-sectional findings on links between coping and athlete burnout. Specifically, in their study of 421 volleyball athletes, changes in athlete burnout were positively predicted by obsessive passion via its mediated positive association with disengagement-oriented coping behaviors. Overall, as supported in a systematic review of literature (Goodger et al., 2007), the psychological stress and coping model represents a useful, if somewhat rudimentary, conceptual means to understanding athlete burnout. Research conducted from this perspective indicates that perceived stress tends to exacerbate the possibility of an athlete experiencing burnout as do athlete deficits or mismatches in coping skills and resources.

In Smith’s view, athlete burnout was a result of chronic sport-related appraisals of stress that were not effectively mitigated by coping efforts. A variety of cross-sectional research studies have supported links between burnout and perceived stress and deficits in coping resources (e.g., Raedeke & Smith, 2001; 2004). More recently, Schellenberg, Gaudreau, and Crocker (2013) provided longitudinal evidence in a study of passionate involvement in sport supporting earlier cross-sectional findings on links between coping and athlete burnout. Specifically, in their study of 421 volleyball athletes, changes in athlete burnout were positively predicted by obsessive passion via its mediated positive association with disengagement-oriented coping behaviors. Overall, as supported in a systematic review of literature (Goodger et al., 2007), the psychological stress and coping model represents a useful, if somewhat rudimentary, conceptual means to understanding athlete burnout. Research conducted from this perspective indicates that perceived stress tends to exacerbate the possibility of an athlete experiencing burnout as do athlete deficits or mismatches in coping skills and resources.

The second historical burnout conceptualization, offered by Coakley (1992), involved a focus on the sociological factors that may contribute to athlete burnout. Based on data from qualitative interviews with adolescent athletes, Coakley (1992) concluded that burnout, conceptualized as a particular type of withdrawal from sport, was the result of environmental constraints rather than the individual’s responses to stress per se. Specifically, Coakley posited that this particular type of withdrawal from sport resulted from the development of a unidimensional sport identity and the individual athlete’s perceived lack of control over his or her sport participation. This perspective has received very limited empirical support; the exception is the partial support found in one study of competitive swimmers (Black & Smith, 2007). Despite limited empirical support, this conceptualization does bring important attention to the idea that, beyond individual perceptions of stress or commitment, organizational (or team) factors within intensely competitive youth sport may contribute to athlete burnout (Coakley, 2009). Certainly, this conceptualization has focused additional, necessary attention on the social structure and demands of sporting environments in which athletes participate, rather than solely on individual differences in athlete appraisals of stress as the major contributor to burnout.

Certainly, this conceptualization has focused additional, necessary attention on the social structure and demands of sporting environments in which athletes participate, rather than solely on individual differences in athlete appraisals of stress as the major contributor to burnout.

The third early perspective posited that burnout symptoms could arise from a specific constellation of athletes’ perceptions of their commitment to sport. Building on the broader sport commitment framework proposed by Schmidt and Stein (1991), Raedeke (1997) conceptualized burnout as a potential result of entrapped commitment to sport (as opposed to attraction-based commitment, which has benign or even salutatory effects). Specifically, Raedeke postulated that this maladaptive sport commitment pattern (characterized by a high level of perceived costs, investments, and social constraints along with few perceived benefits or alternatives), if sustained, would result in the athlete’s elevated perceptions of burnout. Support for this conceptualization was found using cluster analytic procedures, with data obtained from a sample of adolescent swimmers (Raedeke, 1997). Specifically, the cluster of swimmers endorsing this entrapped pattern of commitment stress reported the highest levels of burnout symptoms (exhaustion, devaluation, reduced accomplishment). Ultimately, this commitment theory perspective on athlete burnout has received some theoretical support and continues to be used to design and interpret athlete burnout research.

Support for this conceptualization was found using cluster analytic procedures, with data obtained from a sample of adolescent swimmers (Raedeke, 1997). Specifically, the cluster of swimmers endorsing this entrapped pattern of commitment stress reported the highest levels of burnout symptoms (exhaustion, devaluation, reduced accomplishment). Ultimately, this commitment theory perspective on athlete burnout has received some theoretical support and continues to be used to design and interpret athlete burnout research.

Finally, over the last decade or so, researchers have increasingly turned to self-determination theory (SDT; Deci & Ryan, 1985; Ryan & Deci, 2000a, 2000b), a prominent theory of human motivation, as an explanation to advance understanding of athlete burnout. This theory has proven to be exceptionally useful and revealing in those efforts. In SDT, Deci and Ryan contend that satisfaction of basic psychological needs results in optimal human functioning, social development and personal well-being, while the thwarting of psychological needs has the less salubrious results of diminished personal and social functioning and states of ill-being. The psychological needs enumerated in SDT include the needs for autonomy (i.e., to experience behavioral volition), competence (i.e., to perceive oneself as behaviorally effective), and relatedness (to feel socially interconnected with valued others). Satisfaction of these needs is regarded as being universally essential for human health and well-being.

The psychological needs enumerated in SDT include the needs for autonomy (i.e., to experience behavioral volition), competence (i.e., to perceive oneself as behaviorally effective), and relatedness (to feel socially interconnected with valued others). Satisfaction of these needs is regarded as being universally essential for human health and well-being.

In SDT, motivation is considered relative to the broad categories of autonomous and controlled motivation as well as relative to the more specific motivational regulations underlying behavioral enactments (i.e., intrinsic motivation, integrated regulation, identified regulation, introjected regulation, external regulation, amotivation). Autonomous motivation includes self-determined behavioral imperatives to satisfy one’s fundamental psychological needs (i.e., intrinsic motivation) and extrinsic but internalized motivational imperatives that can also satisfy these needs in some degree because they are consistent with one’s identity (i. e., integrated regulation) and/or personal objectives (i.e., identified regulation). Controlled motivation is more externally controlled (and thus less self-determined) and includes behaviors governed by external punishment and reward contingencies (i.e., external regulation) and behaviors resulting from feelings of shame, guilt or pride (i.e., introjected regulation). Finally, amotivation, arguably the motivational signature of athlete burnout (Eklund & Cresswell, 2007), involves behavior without intent to act resulting from not feeling competent, not believing that effort will result in desired outcomes, or not inherently valuing an activity (Ryan & Deci, 2000b).

e., integrated regulation) and/or personal objectives (i.e., identified regulation). Controlled motivation is more externally controlled (and thus less self-determined) and includes behaviors governed by external punishment and reward contingencies (i.e., external regulation) and behaviors resulting from feelings of shame, guilt or pride (i.e., introjected regulation). Finally, amotivation, arguably the motivational signature of athlete burnout (Eklund & Cresswell, 2007), involves behavior without intent to act resulting from not feeling competent, not believing that effort will result in desired outcomes, or not inherently valuing an activity (Ryan & Deci, 2000b).

Evidence supports SDT claims that autonomous behaviors supported by self-authored, or self-determined motivational regulation, are more adaptive, whereas behaviors governed by controlled motivational regulations and amotivation are less adaptive for motivational persistence, psychological health, and well-being (Ryan & Deci, 2000a, 2000b). With regard to athlete burnout, individuals whose experiences fail to satisfy or thwart the aforementioned psychological needs would be expected to exhibit less self-determined forms of sport motivation and, ultimately, higher levels of athlete burnout. Overall, the efficacy of self-determination theory in facilitating researcher efforts and understanding of athlete burnout has been supported in Li, Wang, Pyun, and Kee’s (2013) systematic review of literature in this area.

With regard to athlete burnout, individuals whose experiences fail to satisfy or thwart the aforementioned psychological needs would be expected to exhibit less self-determined forms of sport motivation and, ultimately, higher levels of athlete burnout. Overall, the efficacy of self-determination theory in facilitating researcher efforts and understanding of athlete burnout has been supported in Li, Wang, Pyun, and Kee’s (2013) systematic review of literature in this area.

Review of Current Knowledge Base on Burnout in Sport

Collectively, research guided by the aforementioned theories and models has advanced our understanding of the occurrence and consequences of the athlete burnout syndrome while also serving as a useful guide to informing applied practice in sport (DeFreese, Smith, & Raedeke, 2015). This review of the burnout literature is intended to be representative of the knowledge base and informative as to future work, though it is not absolutely comprehensive. This section describes a pair of larger-scale research projects funded by the U.S. Tennis Association (USTA) and the New Zealand Rugby Union (NZRU) and also highlights important projects that are representative of the key conceptual outcomes of the contemporary burnout knowledge base.

This section describes a pair of larger-scale research projects funded by the U.S. Tennis Association (USTA) and the New Zealand Rugby Union (NZRU) and also highlights important projects that are representative of the key conceptual outcomes of the contemporary burnout knowledge base.

Initial Funded Burnout Projects

The USTA provided support for one of the first funded projects on athlete burnout. The reports emanating from the mixed-methods research endeavor were informative (e.g., Gould, Udry et al., 1996; Gould, Tuffey et al., 1996, 1997) and, not surprisingly given the high-profile nature of the project, have been influential. The investigation was grounded in Gould’s (1996) conceptualization of athlete burnout as a motivational response to sport participation. He maintained that the commonly reported decreases in sport motivation observed among athletes reported as being “burned out” were the result of their prior highly motivated sport engagement involving chronic exposure to stress in their sport involvements. In observing that the stress encountered by athletes could be psychological and/or the result of training stress, Gould argued that burnout could be experienced either psychologically or physically. Some support for his position was found among the elite adolescent tennis players taking part in the USTA study (Gould, Udry et al., 1996; Gould, Tuffey et al., 1996, 1997). Specifically, athlete burnout was associated with less adaptive forms of motivation (i.e., amotivation), lower self-reported use of coping skills, high levels of perfectionism, and social pressures from parents or coaches. This research was integral to the early understanding of athletes’ burnout experiences and served as a guide for much of the subsequent research conducted in the area. In sum, the USTA study was important even if its eclectic conceptual grounding and use of an early tenuous measure of athlete burnout present some challenges for interpretation.

In observing that the stress encountered by athletes could be psychological and/or the result of training stress, Gould argued that burnout could be experienced either psychologically or physically. Some support for his position was found among the elite adolescent tennis players taking part in the USTA study (Gould, Udry et al., 1996; Gould, Tuffey et al., 1996, 1997). Specifically, athlete burnout was associated with less adaptive forms of motivation (i.e., amotivation), lower self-reported use of coping skills, high levels of perfectionism, and social pressures from parents or coaches. This research was integral to the early understanding of athletes’ burnout experiences and served as a guide for much of the subsequent research conducted in the area. In sum, the USTA study was important even if its eclectic conceptual grounding and use of an early tenuous measure of athlete burnout present some challenges for interpretation.

A subsequent series of studies funded by the New Zealand Rugby Union (NZRU) also contributed to the knowledge base on athlete burnout on conceptual, measurement, and methodological accounts. As a starting point, interviews with 15 rugby athletes endorsing elevated burnout symptoms about their experiences with burnout supported the relevance of the burnout syndrome and highlighted several key burnout antecedents in the rugby environment, including competitive transitions, heavy playing and training demands, and social pressures to comply with demands despite physical or mental fatigue (Cresswell & Eklund, 2006c). A multitrait–multimethod assessment of athlete burnout measurement provided important evidence indicating that psychometrically valid and reliable data could be obtained with the ABQ and that burnout in elite rugby athletes was psychometrically related but nonetheless distinct from depression (Cresswell & Eklund, 2006b). Across the series of studies, consistent evidence was obtained indicating that athlete burnout was associated with less self-determined forms of motivation among professional and top amateur rugby players (Cresswell & Eklund, 2004, 2005b, 2005c).

As a starting point, interviews with 15 rugby athletes endorsing elevated burnout symptoms about their experiences with burnout supported the relevance of the burnout syndrome and highlighted several key burnout antecedents in the rugby environment, including competitive transitions, heavy playing and training demands, and social pressures to comply with demands despite physical or mental fatigue (Cresswell & Eklund, 2006c). A multitrait–multimethod assessment of athlete burnout measurement provided important evidence indicating that psychometrically valid and reliable data could be obtained with the ABQ and that burnout in elite rugby athletes was psychometrically related but nonetheless distinct from depression (Cresswell & Eklund, 2006b). Across the series of studies, consistent evidence was obtained indicating that athlete burnout was associated with less self-determined forms of motivation among professional and top amateur rugby players (Cresswell & Eklund, 2004, 2005b, 2005c).

The NZRU investigation also involved some of the earliest longitudinal research efforts, two of which were quantitative and one was qualitative. In the first instance, a 30-week “rugby year” monitoring study (Cresswell & Eklund, 2006a) was conducted to assess burnout experiences across time for athletes playing in multiple tournaments representing different teams (e.g., club, provincial, national) at different points in time. Data were collected from professional players (n = 109) at three time points (i.e., at the end of precompetitive training, approximately 10 weeks later during the season, and finally at approximately 30 weeks—during the final weeks of regular games). In hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) analyses, statistically significant variation was observed over time in burnout dimensions of reduced accomplishment and exhaustion but, contrary to expectations, in a nonlinear fashion. Players reported an increase in reduced accomplishment by the second time point, but further increases were not observed in the closing weeks of the rugby year. Changes on the exhaustion dimension varied across time by position (i.e., backfield and forward players), with the backs reporting a sharper decrease in exhaustion at midseason measurement than forwards and a subsequent sharper increase at the end of the competitive year.

Changes on the exhaustion dimension varied across time by position (i.e., backfield and forward players), with the backs reporting a sharper decrease in exhaustion at midseason measurement than forwards and a subsequent sharper increase at the end of the competitive year.

In a separate study assessing both burnout and SDT motivational constructs, changes in burnout were again observed among athletes over the course of a 12-week tournament (Cresswell & Eklund, 2005a). Data in this tournament within the “rugby year” were also collected at three time points (pre-tournament, mid-tournament, and end of tournament) from professional rugby players (n = 102). Significant variation over time in burnout was only observed in the reduced accomplishment dimension, and a significant team by time interaction suggested that the variation was due to more than just game outcomes. As expected, amotivation was positively associated with end of tournament burnout, and self-determined motivation was inversely associated with burnout perceptions at this later period. A number of other pragmatic factors of interest were also associated with the key characteristics of burnout across time in the HLM analyses, including win/loss ratio, injury, starting status, playing position, experience, and team membership.

A number of other pragmatic factors of interest were also associated with the key characteristics of burnout across time in the HLM analyses, including win/loss ratio, injury, starting status, playing position, experience, and team membership.

In the third longitudinal qualitative study (Cresswell & Eklund, 2007), interview data were obtained from professional players (n = 9) and members of team management (n = 3), and again at three time points (pre-season, mid-season and end of season) over a 12-month period. These data revealed that there was a dynamic element to athletes’ experiences of burnout over the course of the year that included periods of positive and negative change over the time frame. These data also suggested that elevations in perceptions of burnout were attributed to matters such as playing and training demands, competitive transitions, injury, and pressures from coaches/administrators, as well as from the media.

As with the USTA-funded project, the studies conducted in the NZRU project advanced the extant literature on athlete burnout on both conceptual and empirical grounds. Unlike the USTA project, however, the NZRU studies occurred at a time when other active programs of research were also emerging within the field—which is to say that research inquiry on athlete burnout was on the uptick at that time. Perhaps most notably, Lemyre and his colleagues (e.g., Lemyre, Hall, & Roberts, 2008; Lemyre, Treasure, & Roberts, 2006; Lemyre, Roberts, & Stray-Gundersen, 2007), as well as Lonsdale and his colleagues (e.g., Lonsdale, Hodge, & Rose, 2006, 2009; Hodge, Lonsdale, & Ng, 2008) were also conducting important studies on athlete burnout, also typically grounded in SDT, at a time overlapping with the NZRU studies. In short, subsequent to the USTA project and the arrival of the ABQ, athlete burnout has emerged as a topic of focal interest within sport psychology wherein the sophistication and number of articles published has noticeably increased year on year.

Unlike the USTA project, however, the NZRU studies occurred at a time when other active programs of research were also emerging within the field—which is to say that research inquiry on athlete burnout was on the uptick at that time. Perhaps most notably, Lemyre and his colleagues (e.g., Lemyre, Hall, & Roberts, 2008; Lemyre, Treasure, & Roberts, 2006; Lemyre, Roberts, & Stray-Gundersen, 2007), as well as Lonsdale and his colleagues (e.g., Lonsdale, Hodge, & Rose, 2006, 2009; Hodge, Lonsdale, & Ng, 2008) were also conducting important studies on athlete burnout, also typically grounded in SDT, at a time overlapping with the NZRU studies. In short, subsequent to the USTA project and the arrival of the ABQ, athlete burnout has emerged as a topic of focal interest within sport psychology wherein the sophistication and number of articles published has noticeably increased year on year.

Theoretical Elaboration and Extension in Athlete Burnout Research

The bulk of the motivationally grounded athlete burnout research in the last decade or so has often been grounded in SDT although other theories (e. g., achievement goal theory) that also make differentiations in motivational qualities have also been employed. Sport psychology researchers have found considerable intuitive appeal in the notions that the quality of athlete motivation or athlete unsatisfied fundamental psychological needs might cause and/or mediate the emergence of aversive sport-based involvement experiences. Overall, theory testing investigations in the area, including cross-sectional and longitudinal designs, have been informative for developing understanding of processes involved in burnout in sport settings.

g., achievement goal theory) that also make differentiations in motivational qualities have also been employed. Sport psychology researchers have found considerable intuitive appeal in the notions that the quality of athlete motivation or athlete unsatisfied fundamental psychological needs might cause and/or mediate the emergence of aversive sport-based involvement experiences. Overall, theory testing investigations in the area, including cross-sectional and longitudinal designs, have been informative for developing understanding of processes involved in burnout in sport settings.

As a starting point, Lemyre and his colleagues (e.g., Lemyre et al., 2006, 2007, 2008) have conducted prospective design investigations that have been revealing in supporting a SDT explanation of the burnout experience among athletes. They examined the possibility that motivational shifts along a continuum of self-determination could predict athlete burnout symptom development over time among collegiate swimmers (n = 44). Variability in self-determined motivation over a season was indeed found to predict swimmers’ end-of-season burnout symptoms, with shifts toward less self-determined motivational regulations being associated with elevations in athlete burnout. In a related prospective investigation, Lemyre et al. (2007) examined the possibility that beginning-of-season motivation, as operationalized using a self-determination motivational continuum index, could predict end-of-season burnout in elite and junior elite winter sport athletes (n = 141). As expected, end-of-season burnout was significantly predicted by pre-season scores on the self-determined motivation continuum. Interestingly, the prediction of burnout was enhanced when symptoms of overtraining were also included in the analytic model. This pair of studies provided substantial evidence supporting the utility of self-determination theory for understanding athlete burnout. Specifically, athletes experiencing more self-determined forms of motivation endorsed lower burnout scores at the end of the training period assessed in each instance.

Variability in self-determined motivation over a season was indeed found to predict swimmers’ end-of-season burnout symptoms, with shifts toward less self-determined motivational regulations being associated with elevations in athlete burnout. In a related prospective investigation, Lemyre et al. (2007) examined the possibility that beginning-of-season motivation, as operationalized using a self-determination motivational continuum index, could predict end-of-season burnout in elite and junior elite winter sport athletes (n = 141). As expected, end-of-season burnout was significantly predicted by pre-season scores on the self-determined motivation continuum. Interestingly, the prediction of burnout was enhanced when symptoms of overtraining were also included in the analytic model. This pair of studies provided substantial evidence supporting the utility of self-determination theory for understanding athlete burnout. Specifically, athletes experiencing more self-determined forms of motivation endorsed lower burnout scores at the end of the training period assessed in each instance. In a related third study grounded in achievement goal theory rather than SDT, Lemyre, Hall, and Roberts (2008) reported athlete burnout to be positively associated with athlete-endorsed ego/outcome motivational climates (characterized by an emphasis on winning and social comparison) and negatively associated with task/mastery climates (characterized by an emphasis on individual effort and improvement). This pattern of findings was subsequently replicated and extended in research focused specifically on the motivational climate created by teammate peers (Smith, Gustafsson, & Hassmén, 2010) without reference to coaches, parents, or administrators.

In a related third study grounded in achievement goal theory rather than SDT, Lemyre, Hall, and Roberts (2008) reported athlete burnout to be positively associated with athlete-endorsed ego/outcome motivational climates (characterized by an emphasis on winning and social comparison) and negatively associated with task/mastery climates (characterized by an emphasis on individual effort and improvement). This pattern of findings was subsequently replicated and extended in research focused specifically on the motivational climate created by teammate peers (Smith, Gustafsson, & Hassmén, 2010) without reference to coaches, parents, or administrators.

Self-determined motivation has also been examined as a mediator of relationships with athlete burnout (e.g., Appleton & Hill, 2012; Curran, Appleton, Hill, & Hall, 2011; Jowett, Hill, Hall, & Curran, 2013) or, alternatively, as an adaptive psychological outcome in the study of athlete burnout (e.g., DeFreese & Smith, 2013b). Curran et al. (2011), for example, found support for the hypothesis that the relationship between harmonious passion and burnout would be mediated by self-determined motivation in cross-sectional data obtained from a sample of male elite junior soccer players (n = 149). In contrast, DeFreese and Smith (2013b) found teammate social support satisfaction and perceived availability of support to be both positively associated with self-determined motivation and negatively associated with burnout in cross-sectional data obtained from collegiate American football athletes (n = 235).

Curran et al. (2011), for example, found support for the hypothesis that the relationship between harmonious passion and burnout would be mediated by self-determined motivation in cross-sectional data obtained from a sample of male elite junior soccer players (n = 149). In contrast, DeFreese and Smith (2013b) found teammate social support satisfaction and perceived availability of support to be both positively associated with self-determined motivation and negatively associated with burnout in cross-sectional data obtained from collegiate American football athletes (n = 235).

Finally, Lonsdale and Hodge (2011) considered the temporal question on the causal sequencing of relationships between burnout and self-determined motivation and showed that that lower levels of self-determined motivation preceded the development of burnout. Though not settling the matter of causal sequencing definitively, their findings did provide support for a self-determination theory grounded explanation of athlete burnout.

Relative to the basic psychological needs subtheory of SDT, researchers have also examined satisfaction of the fundamental psychological needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness and their association with burnout in athlete populations. Research on elite rugby players found that players classified as “high-burnouts” reported lower perceptions of need fulfillment compared to “low burnouts” (Hodge, Lonsdale, & Ng, 2008). Interestingly, however, research has also suggested that simultaneous satisfaction of psychological needs is associated with lower levels of athlete burnout than satisfaction of any psychological need individually (Perreault, Gaudreau, Lapointe, & Lacroix, 2007). Finally, an inverse relationship between psychological need satisfaction and athlete burnout has been reported in data from elite Canadian athletes (n = 201) showcasing self-determined motivation as a potential mediator of the relationship (Lonsdale, Hodge, & Rose, 2009). In sum, self-determination theory has received considerable support in the extant literature as an effective means to understand athlete motivation and psychological health outcomes, including burnout. That said, motivation may be understood through a variety of other theoretical conceptualizations (e.g., achievement goal theory, attribution theory). Acordingly, self-determination theory is not the only potentially useful motivational framework for the conceptual grounding of athlete burnout research.

That said, motivation may be understood through a variety of other theoretical conceptualizations (e.g., achievement goal theory, attribution theory). Acordingly, self-determination theory is not the only potentially useful motivational framework for the conceptual grounding of athlete burnout research.

Coaching and Athlete Burnout

Burnout researchers have also conducted studies examining the potential influence of sport-based social agents on athlete burnout. Of note, the impact of significant others (e.g., coaches) was highlighted in both the USTA and NZRU research programs. Thus, coaches are key members of the sport-based training and competition environment, and their influence on athletes is nontrivial. The idea that coaching styles and behaviors may contribute to the experiences of burnout among athletes seems logical, perhaps especially given earlier evidence that the burnout being experienced by coaches may elevate the risk of burnout among their athletes (Price & Weiss, 2000; Vealey, Armstrong, Comar, & Greenleaf, 1998). Recent theoretically grounded studies of coaching styles and behaviors relative to athlete burnout have revealed that coach interactions with athletes are worthy of consideration in the matter; perhaps even as a potential focus of burnout intervention efforts (e.g., Barcza-Renner, Eklund, Morin, & Habeeb, 2016; DeFreese et al., 2015; González, García-Merita, Castillo, & Balaguer, 2015).

Recent theoretically grounded studies of coaching styles and behaviors relative to athlete burnout have revealed that coach interactions with athletes are worthy of consideration in the matter; perhaps even as a potential focus of burnout intervention efforts (e.g., Barcza-Renner, Eklund, Morin, & Habeeb, 2016; DeFreese et al., 2015; González, García-Merita, Castillo, & Balaguer, 2015).

As a first example, the González et al. (2015) longitudinal investigation implicates the leadership style provided by coaches in working with their athletes as a potential antecedent of athlete burnout. Specifically, González et al. (2015) reported the results of a two-season SDT-grounded prospective investigation of associations between athlete-perceived coaching styles and athlete outcomes of well- and ill-being (respectively, self-esteem and burnout). Among the 360 male youth soccer athletes sampled, athlete perceptions of an autonomy-supportive coaching style were found to be positively associated with self-esteem development across seasons and negatively associated with the development of burnout via a positive association with psychological need satisfaction and a negative association with psychological need thwarting. Athlete perceptions of a controlling coaching style, however, were negatively associated with development of self-esteem across seasons and positively associated with the development of burnout via negative association with psychological need satisfaction and positive association with psychological need thwarting. Ultimately, longitudinal assessment of the association of athlete perceptions of coaching behaviors with athlete burnout perceptions supports the idea that coaching styles may have a developmental impact on athlete psychological health and well-being. This position merits continued examination across athlete ages and competition levels.

Athlete perceptions of a controlling coaching style, however, were negatively associated with development of self-esteem across seasons and positively associated with the development of burnout via negative association with psychological need satisfaction and positive association with psychological need thwarting. Ultimately, longitudinal assessment of the association of athlete perceptions of coaching behaviors with athlete burnout perceptions supports the idea that coaching styles may have a developmental impact on athlete psychological health and well-being. This position merits continued examination across athlete ages and competition levels.

Barcza-Renner et al. (2016) extended research in this area by examining the potential mediating effects of athlete perfectionism and motivation on the relationship between controlling coaching behaviors (as opposed to the more general controlling coaching style) and athlete burnout. Division I NCAA collegiate swimmers (n = 487) provided cross-sectional data for analysis within three weeks of their conference championship meet. Athlete perceptions of controlling coaching behavior were predictive of athletes’ socially prescribed and self-oriented perfectionism and their motivation (i.e., autonomous, amotivation). Specifically, self-oriented perfectionism was positively associated with autonomous motivation and negatively associated with amotivation. In contrast, socially prescribed perfectionism was negatively associated with autonomous motivation and positively associated with controlled motivation and amotivation. Autonomous motivation and amotivation, in turn, predicted athlete burnout in expected directions. Support for the potential mediating effects was observed in modeling results, with significant indirect effects across model pathways. Overall, these results also support self-determination theory contentions that the social context of engagement has motivational implications for the health and well-being of involved actors in sport.

Athlete perceptions of controlling coaching behavior were predictive of athletes’ socially prescribed and self-oriented perfectionism and their motivation (i.e., autonomous, amotivation). Specifically, self-oriented perfectionism was positively associated with autonomous motivation and negatively associated with amotivation. In contrast, socially prescribed perfectionism was negatively associated with autonomous motivation and positively associated with controlled motivation and amotivation. Autonomous motivation and amotivation, in turn, predicted athlete burnout in expected directions. Support for the potential mediating effects was observed in modeling results, with significant indirect effects across model pathways. Overall, these results also support self-determination theory contentions that the social context of engagement has motivational implications for the health and well-being of involved actors in sport.

An organizational psychology perspective that may be useful in the continued examination of athlete perceptions of social actors, including coaches, on their sport experience can be found in Leiter and Maslach’s (2004) areas of worklife conceptual framework. As adapted to sport by DeFreese et al. (2015), this framework is grounded in the notion that athletes’ satisfaction with perceptions of the congruence or “fit” of their interests/values as an athlete and the interests/values of actors in their sport organizations (i.e., coaches, administrators) have implications for their psychological outcomes. Incongruences were hypothesized to be associated with elevations in athlete burnout; whereas, good athlete-sport organization “fits” were expected to be associated with more adaptive psychological outcomes. Examination of data from a sample of collegiate American football athletes (n = 235) provided support for this conceptual perspective (DeFreese & Smith, 2013a). Regardless of the framework used, however, research to date supports the importance of coaches to their athletes’ sport-based burnout experiences. Overall, the athletes’ relationships with their coaches and other sport organizational social agents can shape their perceptions of sport involvement and burnout.