How did Pan African women of faith gather to advocate for global nutrition. What was the theme of the three-day summit in Washington, D.C. How did the summit commemorate the 400th anniversary of enslaved Africans arriving in Jamestown.

The Gathering of Pan African Women of Faith

In November 2019, a powerful convergence of 75 Pan African women of faith took place in Washington, D.C. This three-day summit, aptly named “African at Heart,” brought together women from diverse backgrounds to advocate for global nutrition and empower each other to reshape the narrative surrounding Pan-African people worldwide.

The timing of this gathering was particularly significant, as it coincided with the 400th anniversary of the arrival of enslaved African peoples to Jamestown, Virginia. This historical context added depth and poignancy to the summit’s proceedings.

The Significance of the Summit

Rev. Dr. Angelique Walker-Smith, senior associate for Pan African and Orthodox Church Engagement at Bread for the World, emphasized the importance of this gathering: “It was timely to bring Pan African Women of Faith together to advocate for global nutrition and to remember the transatlantic slave trade in 1619 during our spiritual pilgrimage.”

She further elaborated on the unique position of these women: “They are disproportionately affected by global nutrition concerns and related intersectional issues linked to historic root causes. They are the children or kindred of the ancestors of the transatlantic slave trade in some way.”

A Spiritual Pilgrimage Through History

The summit began with a profound spiritual journey that connected participants to the rich tapestry of African American history and struggle. This pilgrimage included visits to several iconic locations:

- The National Museum of African American History and Culture

- The home of Frederick Douglass, who escaped slavery to become a prominent abolitionist leader

- The Martin Luther King Jr. monument

For many participants, this experience was deeply moving. Princess Sekyere, founder of a nonprofit empowering women and girls in Ghana, shared her thoughts: “The pilgrimage was an eye-opener. It was really revealing and inspiring for me. I’m so excited to be in D.C. This city is very symbolic of the American story.”

Global Representation and Unity

The summit’s strength lay in its diverse representation, with attendees hailing from various countries and regions:

- Angola

- Congo

- Brazil

- Bahamas

- Nigeria

- Ghana

- Various cities across the United States

This international gathering fostered a sense of unity and shared purpose among Pan African women from different corners of the globe.

Honoring Pan-African Women Changemakers

The summit’s first day concluded with a powerful evening at Ebenezer United Methodist Church, a historic Washington landmark that has hosted numerous African American icons. The event paid homage to Pan African women changemakers and included prayers honoring ancestors.

Ann Kioi, representing the All Africa Conference of Churches in Kenya, delivered a stirring message: “Africans should take pride in their heritage and take charge of their lives. This is what makes me feel that I am an African at heart. I share the same destiny, and I celebrate my diversity as an African.”

Advocacy on Capitol Hill

A key component of the summit was its focus on advocacy. Participants engaged in direct action by visiting the offices of nearly a dozen House and Senate members. Their mission was to urge lawmakers to support specific resolutions:

- H.Res.189

- S.Res.260

These resolutions recognize the importance of continued United States leadership in accelerating global progress against maternal and child malnutrition.

Thursdays in Black Campaign

In a powerful show of solidarity, summit attendees chose to wear black as part of the “Thursdays in Black” campaign. Launched by the World Council of Churches, this initiative aims to draw attention to the pervasive issue of gender-based violence.

Tiauna Webb, a first-time summit attendee from Chicago, emphasized the significance of this action: “Not only are we trying to push for equitable treatment of women around the world, but we’re also embodying it here.”

Inspiring Words from Political Leaders

The summit featured powerful speeches from influential political figures, including:

- Rep. Jahanna Hayes (D-CT), the first African American woman from Connecticut to serve in Congress

- Rep. Alma Adams (D-NC)

Rep. Hayes shared her personal experience with social support systems: “At the point where I couldn’t stand on my own, I relied on WIC. I relied on food stamps. I relied on lunch for my kids. And I know, as a Christian, that now I have a responsibility to do the same thing for somebody else.”

Insights from a Global Food Security Expert

On the final day of the summit, attendees had the privilege of hearing from Ertharin Cousin, a former United Nations ambassador who served as executive director of the World Food Programme from 2012 to 2017. Cousin delivered a powerful message urging the women to use their collective voices to ensure access to nutritious food globally.

“Embracing your theme, African at Heart, demands a shared vision of what is possible on both sides of the pond,” Cousin stated. “There is nothing shameful, unrealistic, or naïve about wanting a better world.”

Planning for the Future

The summit concluded with a series of breakout sessions where participants exchanged ideas and formulated plans of action. These discussions resulted in a range of recommendations, including the development of a faith-based advocacy agenda.

This forward-looking approach ensured that the momentum generated during the summit would continue long after the event’s conclusion, empowering Pan African women to drive change in their communities and on the global stage.

The Impact of Unity and Shared Purpose

The “African at Heart” summit demonstrated the power of bringing together diverse voices united by a common heritage and shared goals. By combining advocacy, spiritual reflection, and strategic planning, the event created a platform for Pan African women to address critical issues affecting their communities worldwide.

As these women returned to their respective countries and regions, they carried with them not only new knowledge and strategies but also a renewed sense of purpose and connection to their Pan African identity.

Addressing Global Nutrition Through a Pan African Lens

One of the central themes of the summit was the critical issue of global nutrition. Why is this topic particularly relevant to Pan African communities? The historical and ongoing impacts of colonialism, structural inequality, and climate change have disproportionately affected food security and nutrition in many African countries and communities of African descent worldwide.

By advocating for improved global nutrition policies, summit participants were addressing not only immediate health concerns but also broader issues of equity and justice. Their efforts highlight the interconnectedness of nutrition, poverty, education, and overall community well-being.

The Role of Faith in Advocacy and Empowerment

The summit’s focus on women of faith underscores the important role that religious communities can play in addressing social issues. How does faith inform and motivate advocacy efforts? For many participants, their spiritual beliefs provided a foundation for their commitment to social justice and community empowerment.

Faith communities often serve as important social networks and sources of support, particularly in marginalized communities. By harnessing these networks for advocacy and education, the summit participants aimed to create sustainable, community-driven change.

Bridging the Diaspora

The diverse geographical representation at the summit highlighted the global nature of the Pan African experience. How can connections between African nations and diaspora communities strengthen advocacy efforts? By sharing experiences, strategies, and resources across borders, Pan African women can create more robust and effective campaigns for change.

These cross-cultural exchanges also serve to reinforce a sense of shared identity and purpose, countering narratives that seek to divide or diminish Pan African communities.

The Intersection of Gender and Pan African Identity

The summit’s focus on women’s voices brings attention to the unique challenges and perspectives of Pan African women. How do gender issues intersect with racial and cultural identity in the context of global advocacy? By centering women’s experiences and leadership, the summit contributed to a more nuanced and inclusive approach to Pan African empowerment.

The “Thursdays in Black” campaign participation also highlighted the ongoing struggle against gender-based violence, demonstrating how Pan African women are connecting their advocacy to broader global movements for gender equality.

Looking to the Future: Sustainable Advocacy

As the summit concluded, participants faced the challenge of translating the event’s energy and insights into lasting change. How can the momentum of such gatherings be maintained over time? The focus on developing concrete action plans and a faith-based advocacy agenda suggests a commitment to long-term, strategic engagement with issues of global nutrition and Pan African empowerment.

By fostering ongoing connections between participants and creating platforms for continued collaboration, the summit organizers aimed to create a sustainable network of Pan African women leaders capable of driving change at local, national, and international levels.

The Power of Narrative in Shaping Identity and Action

A key theme of the summit was the idea of “re-righting” the narrative of Pan African people around the world. Why is control over narrative so crucial in the context of advocacy and empowerment? Historical narratives have often been used to justify oppression and marginalization of African and African-descended peoples.

By reclaiming and reshaping these narratives, Pan African women can challenge stereotypes, assert their agency, and inspire new generations to take pride in their heritage and work towards positive change. The summit’s blend of historical reflection and forward-looking action exemplifies this approach to narrative empowerment.

Leveraging Political Engagement for Change

The summit’s inclusion of direct advocacy on Capitol Hill and engagement with political leaders highlights the importance of political action in achieving social change. How can grassroots movements effectively influence policy at national and international levels? By combining personal stories, data-driven arguments, and collective action, the summit participants demonstrated a multifaceted approach to political engagement.

The presence of political leaders like Rep. Jahanna Hayes and Rep. Alma Adams at the summit also underscores the potential for building alliances between community advocates and elected officials, creating pathways for community concerns to be translated into policy action.

The Role of International Organizations in Pan African Advocacy

The involvement of organizations like Bread for the World, the World Council of Churches, and the African Union in organizing the summit points to the importance of international collaboration in addressing global issues. How do these partnerships amplify the voices of Pan African women? By providing resources, platforms, and connections to global networks, international organizations can help local advocates scale up their efforts and reach broader audiences.

These partnerships also facilitate the exchange of best practices and the development of coordinated strategies across different regions and contexts, strengthening the overall impact of Pan African advocacy efforts.

Education and Empowerment: Key Tools for Change

The summit’s emphasis on learning and sharing knowledge highlights the crucial role of education in empowerment and advocacy. How does increased awareness of history, policy, and global issues enhance the effectiveness of advocacy efforts? By equipping participants with a deeper understanding of the complex factors influencing global nutrition and Pan African communities, the summit aimed to create more informed and strategic advocates.

This focus on education extends beyond the summit itself, as participants were encouraged to share their knowledge and insights with their home communities, creating a ripple effect of awareness and engagement.

Celebrating Diversity Within Pan African Identity

The gathering of women from various countries and backgrounds at the summit showcased the rich diversity within Pan African communities. How does this diversity strengthen the movement for Pan African empowerment? By bringing together a wide range of perspectives and experiences, the summit fostered a more comprehensive understanding of the challenges and opportunities facing Pan African communities globally.

This diversity also challenges monolithic perceptions of African and African-descended peoples, highlighting the complex and multifaceted nature of Pan African identity in the 21st century.

The Ongoing Journey of Pan African Empowerment

As the “African at Heart” summit demonstrated, the work of Pan African empowerment and advocacy is an ongoing journey. By bringing together women of faith from across the globe, the event created a powerful space for reflection, learning, and action. The connections forged, strategies developed, and commitments made during these three days in Washington, D.C. have the potential to ripple out, influencing communities and policies far beyond the summit itself.

As these women continue their work in their respective spheres of influence, they carry with them not only new knowledge and skills but also a renewed sense of purpose and connection to their shared Pan African heritage. Their efforts to address global nutrition, challenge oppressive narratives, and empower their communities represent a continuation of the long struggle for justice and equality that has defined the Pan African experience.

The “African at Heart” summit serves as a reminder of the power of collective action and the enduring strength of Pan African identity in the face of ongoing challenges. As these women of faith continue to advocate, educate, and inspire, they contribute to a legacy of resilience and hope that spans continents and generations.

African at Heart | Bread for the World

African at Heart

November 22, 2019

By Lacey Johnson

Seventy-five Pan African women of faith gathered in Washington, D.C., in November to advocate for global nutrition on Capitol Hill and empower one another to “re-right” the narrative of Pan-African people around the world.

The three-day summit, themed “African at Heart,” also observed the 400th anniversary of the arrival of enslaved African peoples to Jamestown, Virginia.

“It was timely to bring Pan African Women of Faith together to advocate for global nutrition and to remember the transatlantic slave trade in 1619 during out spiritual pilgrimage,” said Rev. Dr. Angelique Walker-Smith, senior associate for Pan African and Orthodox Church Engagement at Bread for the World.

She added: “They are disproportionately affected by global nutrition concerns and related intersectional issues linked to historic root causes. They are the children or kindred of the ancestors of the transatlantic slave trade in some way. ”

”

The gathering kicked off with a spiritual pilgrimage beginning at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, followed by a visit to the home of Fredrick Douglass, who escaped slavery in 1838 to become a national leader of the abolitionist movement. The trip closed with prayers at the foot of the Martin Luther King Jr. monument.

“The pilgrimage was an eye-opener. It was really revealing and inspiring for me,” said Princess Sekyere, who founded a nonprofit that works to empower women and girls in her home country of Ghana. “I’m so excited to be in D.C. This city is very symbolic of the American story.”

Sekyere was among the numerous women who traveled internationally to be at the summit, which welcomed attendees from Angola, Congo, Brazil, Bahamas, Nigeria, Ghana, and cities all over the United States.

Paying homage to Pan-African women changemakers

The first day of the summit concluded with dinner, prayers, and presentations at Ebenezer United Methodist Church—an historic Washington landmark that has hosted African American icons like Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, and W. E.B. Du Bois. The evening included a presentation paying homage to Pan African women changemakers from around the world, as well as prayers honoring ancestors that came before.

E.B. Du Bois. The evening included a presentation paying homage to Pan African women changemakers from around the world, as well as prayers honoring ancestors that came before.

“Africans should take pride in their heritage and take charge of their lives,” said Ann Kioi, the programmes development and fundraising officer at All Africa Conference of Churches in Kenya, speaking from the pulpit. “This is what makes me feel that I am an African at heart. I share the same destiny, and I celebrate my diversity as an African.”

The summit was hosted by the Pan African Women of Faith of Bread for the World, Pan African Women’s Ecumenical Empowerment Network (PAWEEN) of the World Council of Churches, and the African Union in partnership with the All Africa Conference of Churches.

Women broke into groups to visit the offices of nearly a dozen House and Senate members on the second day of the summit. They urged lawmakers to support H.Res.189 and S.Res.260, which recognize the importance of continued United States leadership to accelerate global progress against maternal and child malnutrition.

They also chose to wear black as part of a “Thursdays in Black” campaign launched by the World Council of Churches to draw attention to the problem of gender-based violence.

“This issue is so important,” said Tiauna Webb, a first-time summit attendee from Chicago. “Not only are we trying to push for equitable treatment of women around the world, but we’re also embodying it here.”

A reception that evening featured a powerful speech by Rep. Jahanna Hayes (D-CT), as well as a surprise visit from Rep. Alma Adams (D-NC).

“At the point where I couldn’t stand on my own, I relied on WIC. I relied on food stamps. I relied on lunch for my kids,” said Hayes, who, in January, became the first African American woman from Connecticut to serve in Congress. “And I know, as a Christian, that now I have a responsibility to do the same thing for somebody else.”

‘Wanting a better world’

On the last day of the summit, attendees gathered at Bread’s headquarters for a special visit with Ertharin Cousin, a former United Nations ambassador who served as executive director of the World Food Programme from 2012 to 2017.

Cousin urged the women to use their collective voices to ensure people have access to nutritious food, whether it is in Sub-Saharan Africa or South Carolina.

“Embracing your theme, African at Heart, demands a shared vision of what is possible on both sides of the pond,” she said. “There is nothing shameful, unrealistic, or naïve about wanting a better world.”

Before departing, the women broke into groups to exchange ideas and formulate plans of action going forward. A range of recommendations inclusive of a faith-based advocacy agenda related to ending hunger and poverty emerged.

“We are one, no matter our differences,” said Kari Cooke, a deaf summit attendee and longtime advocate for disability rights. “Just sharing that with black women all over the world is very powerful and reminds us that we are not alone, and we will never be alone. We will continue to do this work.”

Lacey Johnson is a freelance writer and photographer in Washington, D.C.

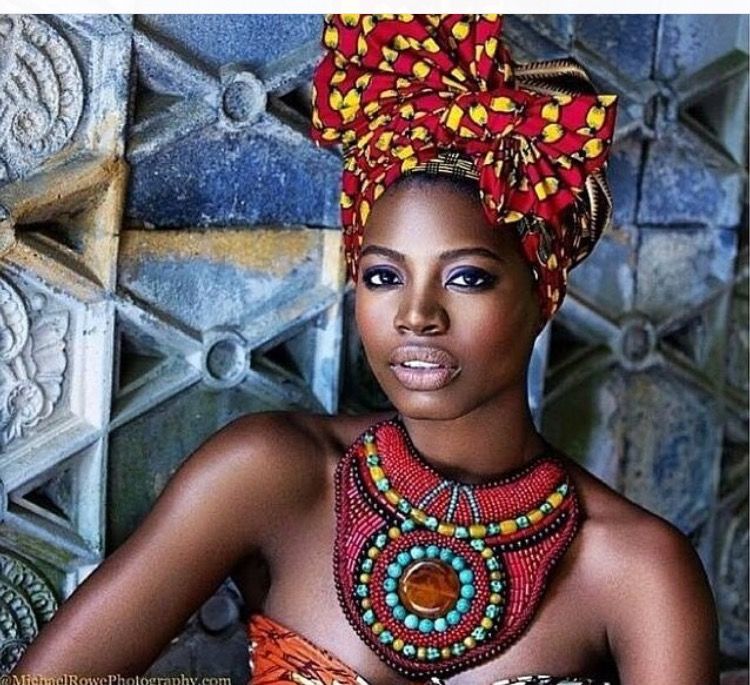

Seventy-five Pan African women of faith gathered in Washington, D. C. to advocate for global nutrition and empower one another to “re-right” the narrative of Pan-African people. The three-day summit, themed “African at Heart,” also observed the 400th anniversary of the arrival of enslaved African peoples to Jamestown, Virginia. Photo: Howard Wilson for Bread for the World.

C. to advocate for global nutrition and empower one another to “re-right” the narrative of Pan-African people. The three-day summit, themed “African at Heart,” also observed the 400th anniversary of the arrival of enslaved African peoples to Jamestown, Virginia. Photo: Howard Wilson for Bread for the World.

The Boy with the African Heart

Written by Nicholas Wright and Robert Jones

Directed by Charles Sturridge

After bringing her deteriorating brother Richard a bowl of porridge, Grace Makutsi rushes off to the No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency. As she arrives at the Kgale Hill shopping center, chickens peck in front of still-closed store fronts and a young worker unlocks Rra Sesupeng’s Treadwell Shoes to discover the shop has been robbed.

“I don’t mean that you are going nowhere.” At the Agency, after sharing an odd rhyming letter from a victim of “the glass ceiling,” Mma Ramotswe puts her foot in her mouth, stating that but for her father’s inheritance she too would be just another woman sitting around someone else’s office. Realizing how that might sound to her secretary, that she assures Grace that she didn’t mean she was going nowhere.

Realizing how that might sound to her secretary, that she assures Grace that she didn’t mean she was going nowhere.

As an angry commotion fills the parking lot, the two women dash out to find an irate Rra Sesupeng blaming his forgetful employee for the shoe shop’s break-in. When the beaten-down assistant pleads his innocence, Precious, deeply offended by Sesupeng’s brutality and quick judgment, decides to investigate the crime scene. Much to the amusement of onlookers, the No. 1 Ladies’ Detective concludes the odd theft of three shoes from three different pairs and a small unlocked window prove children were the culprits. Recommending he install some bars on the window, she reprimands the mean-spirited shop owner for abusing his hard-working assistant.

“We think that we will get over the pain but it never happens.” As Mma Ramotswe and Mma Makutsi evacuate the office over-run by a brood of chickens, an American woman clad in expensive designer wear arrives by taxi. A tightly-wound Andrea Curtin wants to find her son who she fears is no longer alive. An idealistic Stanford graduate, Michael Curtin had come to Botswana to work on a farming commune and mysteriously disappeared 10 years ago. Now that her husband has died, a still-grief stricken Curtin needs closure to start a new life.

An idealistic Stanford graduate, Michael Curtin had come to Botswana to work on a farming commune and mysteriously disappeared 10 years ago. Now that her husband has died, a still-grief stricken Curtin needs closure to start a new life.

When Mma Ramotswe introduces Mma Makutsi as her “secretary,” Mrs. Curtin comments how in the States people no longer use that archaic term – instead staff workers are now assistants or associate executives. To Precious’ consternation, Grace loves the more modern and loftier job titles.

Mrs. Curtin’s son wanted to change the world and thought the greening of the desert was a great way to create a self-sufficient populace. He thrilled his parents with beautiful letters about finding his African heart.

When Michael was initially reported missing, she and her husband Jack jumped on a plane to get to the bottom of things. They talked to many people from the farm, even hiring a bushman tracker named Jo Jo. Despite their exhaustive efforts, what happened to their cherished son remained a total mystery. Michael had simply gone to bed one night and was missing the next day. Eventually, a devastated mother and father gave up their search and went home.

Michael had simply gone to bed one night and was missing the next day. Eventually, a devastated mother and father gave up their search and went home.

“A stale inquiry is unrewarding for all concerned.” Mma Ramotswe decides they must go to the farm, assuring the skeptical American that there will still be echoes of what happened and if they are sensitive enough they will learn something from what remains.

Using common sense, Grace cracks the phone book to track down former commune member Oswald Ranta, now a professor at the University of Botswana. But there is no need to look up Rebecca Soloi because Mma Makutsi already knows the nurse works at a free clinic in Moshupa. “How?” asks Precious. “Coincidence,” is her employee’s vague reply.

On the drive out to the farm, Andrea Curtin shares with Mma Ramotswe her decision of selling the family’s successful business to attend college for African Studies. Just like her son. Still new to Botswana’s generous ways, Curtin wonders if the two women will be safe picking up a little old man hitchhiking. Grateful for the ride, their departing boom-box-toting passenger points them in the direction of Mma Potsane who he knows used to work for the commune.

Grateful for the ride, their departing boom-box-toting passenger points them in the direction of Mma Potsane who he knows used to work for the commune.

At the office, Grace calls Rebecca Soloi asking her not to mention her sick brother when she meets Mma Ramostwe.

“Oh, I’m sorry my sister.” After Mma Ramotswe makes the traditional Botswana introductions, the former housekeeper says she remembers the missing American. Welcoming her visitors to her somewhat meager living situation, Mma Potsane graciously makes them a bowl of maize-meal. Cheerfully, she encourages the detective to remarry, suggesting that policemen, mechanics or ministers make for the best husbands.

At the remains of a once flourishing farm, Mma Potsane suggests it would have been easier to grow grass on your head then to try to grow vegetation in the desert. Privately to Mme Ramotswe, she theorizes that Michael had been carried off by the Kalahari winds.

Inside what was once the medical facility, where Mrs. Curtin remembers nurse Rebecca Soloi being one of the first people to recognize the country’s spreading AIDS scourge, they find a newspaper clipping with a photo of the commune members. A happy Michael stands next to Clara Sedibe, a striking young woman unknown to Andrea Curtin. Mma Potsane points out a recently-made fire, as both she and Mma Ramotswe sense in the winds a spirit that can’t get away.

Curtin remembers nurse Rebecca Soloi being one of the first people to recognize the country’s spreading AIDS scourge, they find a newspaper clipping with a photo of the commune members. A happy Michael stands next to Clara Sedibe, a striking young woman unknown to Andrea Curtin. Mma Potsane points out a recently-made fire, as both she and Mma Ramotswe sense in the winds a spirit that can’t get away.

On the way back, as Africa begins to seep into her being, Andrea marvels at the sight two giraffes fighting to prove their manhood.

At JLB’s for dinner, Precious discusses the case. It’s obvious from the photograph that Clara and Michael had a connection. JLB opines it wise for Precious not to mention the winds because although Americans may be very smart, they do not understand spirits. His rather surly housekeeper rudely clears the plates. According to JLB, she’s jealous of Precious. When Mma Ramotswe states she’s not got a reason to be, Rra Matekoni simply replies, “I know. “

“

After Precious puts the word out that she wishes to speak to Jo Jo, Grace Makutsi asks her boss for a promotion. She doesn’t want more money, just a more fitting title. One that indicates she does some detective work in addition to her secretarial duties. But the aspiring assistant detective’s query is interrupted when BK bursts in with a wardrobe emergency. Only after Precious fixes his pants and drives off does he realize his salon has been broken into. With Mma Ramotswe on the road, Grace investigates. The children have struck again and in her exuberance to prove her case, she breaks off the window latch.

At the Moshupa Clinic, nurse Rebecca Soloi speaks fondly of Mma Makutsi’s great heart before offering some cake to a very pleased Precious Ramotswe. Ten years ago, Mma Soloi’s instincts made her suspicious of Oswald Ranta but now she’s not so sure. Michael definitely had feelings for Clara and they both disappeared that night. So, maybe Precious is looking for two people but she has a feeling Michael Curtin is alive. On her annual trip to her family, she often stops by the abandoned farm. This last time, she too had found the fresh remnants of a fire but also this piece of wood with “Michael Curtin” burnt into it.

On her annual trip to her family, she often stops by the abandoned farm. This last time, she too had found the fresh remnants of a fire but also this piece of wood with “Michael Curtin” burnt into it.

“Does he know if the body is man or woman?” Jo Jo and his granddaughter Doris have been waiting for Mma Ramotswe under an acacia tree. With Doris translating a remorseful Jo Jo says he cannot live with his lie anymore. He had sensed a body buried in an ant hill there. He knows he should’ve told the grieving Curtins but Oswald Ranta threatened harm to him and his family if he said anything. As far as who is lying there, the bushman tells the detective she must dig to find the answer.

Precious’ concern that Clara, and not Michael, might actually be the victim pushes her to ask if Andrea would be able to forgive whoever it is that caused such grief instead of seeking justice’s retribution. Mma Ramotswe explains her country’s traditional belief that if a wrongdoer is truly sorry then the wronged must try to find it in their hearts to forgive them.

At the University, Dr. Ranta’s receptionist is packing up on her last day on the job. With very little prodding, the outraged receptionist reveals that Dr. Ranta slept with her cousin’s daughter in exchange for showing her a final examination. In fact, she sees many female students slink in and out of his office and nobody ever says anything of his sexual harrassment. As the receptionist takes her Agency leaflet, Precious suggests only one person need to tell the truth to stop Dr. Ranta’s abuses.

Inside his office, an empowered Mma Ramotswe, loaded with dirt on the arrogant professor, threatens to expose him if he refuses explain what happened to Michael and Clara. Assured she will not turn him in, the small-minded man states he and Clara had been sleeping together before the idealistic American showed up. Ranta’s suspicions that Michael had stolen Clara’s heart were confirmed when the couple returned from a trip up north where they had gotten married. Betrayed and angry, Ranta violently confronted Clara, but Michael came to her rescue. The two men scuffled before Michael chased Ranta out into the black night. Suddenly, all went quiet until Clara started screaming. Her husband had broken his neck falling into an unseen ditch and died. Deciding that the truth would not be believed, Ranta buried Michael’s body in an anthill. Finally, Ranta reluctantly admits he knows Clara is now running a small hotel up near Maun.

The two men scuffled before Michael chased Ranta out into the black night. Suddenly, all went quiet until Clara started screaming. Her husband had broken his neck falling into an unseen ditch and died. Deciding that the truth would not be believed, Ranta buried Michael’s body in an anthill. Finally, Ranta reluctantly admits he knows Clara is now running a small hotel up near Maun.

On her way out, a triumphant Precious finds the receptionist tacking up a composite of Dr. Ranta’s picture and her Agency leaflet offering help with sexual harassment cases.

“I am Michael Curtin.” Having gotten directions from a lady selling African crafts at the side of the road, Mma Ramotswe finds Clara Curtin and her son Michael Curtin at the Kwane Hotel. Clara had feared telling the crazed Ranta that she was pregnant. Knowing Ranta would try to blame her for her husband’s death, she ran, until settling at the hotel. When young Michael started asking about his daddy, she took him down to the farm, made a fire, and talked and laughed just like she and her husband had once done. Desperate to make amends for hiding the truth, she agrees to tell her husband’s story to his mother.

Desperate to make amends for hiding the truth, she agrees to tell her husband’s story to his mother.

At the Agency, a relieved Clara emerges from her meeting with Andrea Curtin. At peace with what happened to her son, her grandson Michael gives her a small traditional basket. Explaining the woven pattern represents the tears of the giraffe. “Everyone in the world has something to give. But the giraffe has only his tears. They are all he’s got.”

“There is no one on this great continent who I would rather have as an assistant.” When Precious congratulates Grace on her longed-for promotion, a tearful Mma Matuksi feels she in not worthy of the job. She’s feels a coward for not telling Mma Ramotswe of her sick brother. She was ashamed of his disease. But Precious, moved by Grace’s sense of responsibility, tells her assistant detective how brave she’s been.

At the cemetery with her newly-found family, an unburdened Andrea Curtin, adorned in African styles and colors, buries her son. Then Mma Ramotswe takes Mma Makutsi by the hand to her own son’s grave.

Then Mma Ramotswe takes Mma Makutsi by the hand to her own son’s grave.

African Caribbean background and heart health

Professor Nishi Chaturvedi tells Senior Cardiac Nurse Christopher Allen how your ethnic origin can affect your heart and circulatory health

People of African Caribbean heritage make up 1–2 per cent of the UK population, concentrated in major cities, especially London and Birmingham. If you’re of African Caribbean heritage, you may have a higher risk of some heart and circulatory diseases.

Explanations for this are unclear. A strong contender is that African Caribbean communities tend to be in more deprived areas and deprivation can make it harder for a person to have a healthy lifestyle. Genetic differences may also be having an effect, and evidence for this is still being researched.

It’s never too early or too late to make lifestyle changes, such as losing weight and being more physically active.

Even changes made in older age can reduce your risk.

How is your heart health risk different if you have an African Caribbean background?

African Caribbean people have a much higher risk of high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, and stroke, but a lower risk of coronary heart disease (CHD). This is very unusual – normally, high blood pressure and diabetes increase your risk of CHD. This disassociation isn’t yet understood, but we know that on average, cholesterol levels are much better for those of African Caribbean heritage than they are for white Europeans, and this seems to offer some protection against CHD.

If we can understand this mechanism, we could then apply it to other populations. There is evidence that African Caribbean children have some insulin resistance (an early diabetes warning sign) and healthier cholesterol levels, but no difference in blood pressure from the white European population. Higher blood pressure tends to emerge in their teenage years.

There are gender differences, too. African Caribbean men have about a 50 per cent lower risk of CHD than white European men, but for women, the risk is only about 25 per cent lower. This is partly because obesity rates are higher in African Caribbean women than men.

This is partly because obesity rates are higher in African Caribbean women than men.

Do some medications affect African Caribbean people differently?

There’s strong evidence that African Caribbean people respond differently to blood pressure medications. This is reflected in the official guidelines from NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence). Usually, one of the first drugs considered for high blood pressure would be an ACE inhibitor, but African Caribbean people have been shown to respond less well to this. NICE guidance suggests calcium channel blockers, as these have been shown to be more effective in lowering blood pressure in those of African Caribbean heritage.

Early data from the SABRE study [see box below] suggests that blood pressure control is worse in ethnic minorities, but it’s not clear why that is. It may be that the right medication, or a sufficient dose, isn’t being prescribed, or that medications are not always taken, but we need more research to find this out. When someone doesn’t have symptoms and doesn’t feel unwell, it is difficult for them to accept that they have to take medications, possibly for the rest of their life. It’s a very hard message to get across, especially when medications can cause side effects.

When someone doesn’t have symptoms and doesn’t feel unwell, it is difficult for them to accept that they have to take medications, possibly for the rest of their life. It’s a very hard message to get across, especially when medications can cause side effects.

What about attitudes to body shape and exercise?

In African Caribbean communities larger female body shapes are more likely to be seen as something to aspire to. There is therefore less pressure for women to lose weight. Statistics also suggest that women and older people are less likely to exercise. Due to a large number of people in African Caribbean communities being overweight, the issue is normalised.

This is also the case with type 2 diabetes. Because many people are living with the condition and seem fine, it’s seen as inevitable and not taken seriously.

Access to physical activity options is also an issue for those living in deprived areas, where there may be few facilities to exercise safely in a comfortable environment.

Are there other differences in lifestyle risk factors?

There is evidence to suggest African Caribbean people may be more sensitive to the effects of salt on blood pressure. The biology of high blood pressure appears to be different; it’s not that African Caribbean people consume more salt – across the UK, we all eat too much. On the positive side, people of African Caribbean origin tend to smoke less than the overall UK population and drink less alcohol.

CV Nishi Chaturvedi

- Professor of Clinical Epidemiology at University College London

- Worked on some of the largest studies of heart and circulatory disease and diabetes in the UK ethnic minority community

- Member of the BHF Board of Trustees

SABRE study

Much of what we know about ethnic origin and disease risk comes from the Southall and Brent Revisited (SABRE) study. This covered white European, South Asian and African-Caribbean people aged 40–69 in 1988–91. They’ve been followed for 25 years, funded by the BHF, Wellcome Trust, Medical Research Council and Diabetes UK. The focus of investigation, led by Professor Nishi Chaturvedi, is now health in older age.

They’ve been followed for 25 years, funded by the BHF, Wellcome Trust, Medical Research Council and Diabetes UK. The focus of investigation, led by Professor Nishi Chaturvedi, is now health in older age.

East African Heart Rhythm Project

EAST AFRICAN HEART RHYTHM PROJECT

Herzschrittmacher für Ostafrika e.V.

Project manager

Julia Fürstenhoff

Scharnhorststraße 6

D-04275 Leipzig, Germany

Phone +49-341 865 14 10

Fax +49-341 865 14 60

[email protected]

Photos © 2011 – 2013 | PD Dr. Sergio Richter

concept, webdesign & production

THORN Werbeagentur

Mozartstraße 21

D-04109 Leipzig, Germany

Phone +49-341-21 22 744 | Fax +49-341-21 22 745

[email protected] | www.thorn-wa.de

Privacy Policy

We are very delighted that you have shown interest in our enterprise. Data protection is of a particularly high priority for the management of the Herzschrittmacher für Ostafrika e. V.. The use of the Internet pages of the Herzschrittmacher für Ostafrika e.V. is possible without any indication of personal data; however, if a data subject wants to use special enterprise services via our website, processing of personal data could become necessary. If the processing of personal data is necessary and there is no statutory basis for such processing, we generally obtain consent from the data subject.

V.. The use of the Internet pages of the Herzschrittmacher für Ostafrika e.V. is possible without any indication of personal data; however, if a data subject wants to use special enterprise services via our website, processing of personal data could become necessary. If the processing of personal data is necessary and there is no statutory basis for such processing, we generally obtain consent from the data subject.

The processing of personal data, such as the name, address, e-mail address, or telephone number of a data subject shall always be in line with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), and in accordance with the country-specific data protection regulations applicable to the Herzschrittmacher für Ostafrika e.V.. By means of this data protection declaration, our enterprise would like to inform the general public of the nature, scope, and purpose of the personal data we collect, use and process. Furthermore, data subjects are informed, by means of this data protection declaration, of the rights to which they are entitled.

As the controller, the Herzschrittmacher für Ostafrika e.V. has implemented numerous technical and organizational measures to ensure the most complete protection of personal data processed through this website. However, Internet-based data transmissions may in principle have security gaps, so absolute protection may not be guaranteed. For this reason, every data subject is free to transfer personal data to us via alternative means, e.g. by telephone.

1. Definitions

The data protection declaration of the Herzschrittmacher für Ostafrika e.V. is based on the terms used by the European legislator for the adoption of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Our data protection declaration should be legible and understandable for the general public, as well as our customers and business partners. To ensure this, we would like to first explain the terminology used.

In this data protection declaration, we use, inter alia, the following terms:

a) Personal data

Personal data means any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person (“data subject”). An identifiable natural person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identifier such as a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural or social identity of that natural person.

An identifiable natural person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identifier such as a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural or social identity of that natural person.

b) Data subject

Data subject is any identified or identifiable natural person, whose personal data is processed by the controller responsible for the processing.

c) Processing

Processing is any operation or set of operations which is performed on personal data or on sets of personal data, whether or not by automated means, such as collection, recording, organisation, structuring, storage, adaptation or alteration, retrieval, consultation, use, disclosure by transmission, dissemination or otherwise making available, alignment or combination, restriction, erasure or destruction.

d) Restriction of processing

Restriction of processing is the marking of stored personal data with the aim of limiting their processing in the future.

e) Profiling

Profiling means any form of automated processing of personal data consisting of the use of personal data to evaluate certain personal aspects relating to a natural person, in particular to analyse or predict aspects concerning that natural persons performance at work, economic situation, health, personal preferences, interests, reliability, behaviour, location or movements.

f) Pseudonymisation

Pseudonymisation is the processing of personal data in such a manner that the personal data can no longer be attributed to a specific data subject without the use of additional information, provided that such additional information is kept separately and is subject to technical and organisational measures to ensure that the personal data are not attributed to an identified or identifiable natural person.

g) Controller or controller responsible for the processing

Controller or controller responsible for the processing is the natural or legal person, public authority, agency or other body which, alone or jointly with others, determines the purposes and means of the processing of personal data; where the purposes and means of such processing are determined by Union or Member State law, the controller or the specific criteria for its nomination may be provided for by Union or Member State law.

h) Processor

Processor is a natural or legal person, public authority, agency or other body which processes personal data on behalf of the controller.

i) Recipient

Recipient is a natural or legal person, public authority, agency or another body, to which the personal data are disclosed, whether a third party or not. However, public authorities which may receive personal data in the framework of a particular inquiry in accordance with Union or Member State law shall not be regarded as recipients; the processing of those data by those public authorities shall be in compliance with the applicable data protection rules according to the purposes of the processing.

j) Third party

Third party is a natural or legal person, public authority, agency or body other than the data subject, controller, processor and persons who, under the direct authority of the controller or processor, are authorised to process personal data.

k) Consent

Consent of the data subject is any freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous indication of the data subjects wishes by which he or she, by a statement or by a clear affirmative action, signifies agreement to the processing of personal data relating to him or her.

2. Name and Address of the controller

Controller for the purposes of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), other data protection laws applicable in Member states of the European Union and other provisions related to data protection is:

Herzschrittmacher für Ostafrika e.V.

Scharnhorststraße 6

04275 Leipzig

Deutschland

Phone: 0341 865 14 10

Email: [email protected]

Website: https://www.herzschrittmacher-fuer-ostafrika.de/

3. Cookies

The Internet pages of the Herzschrittmacher für Ostafrika e.V. use cookies. Cookies are text files that are stored in a computer system via an Internet browser.

Many Internet sites and servers use cookies. Many cookies contain a so-called cookie ID. A cookie ID is a unique identifier of the cookie. It consists of a character string through which Internet pages and servers can be assigned to the specific Internet browser in which the cookie was stored. This allows visited Internet sites and servers to differentiate the individual browser of the dats subject from other Internet browsers that contain other cookies. A specific Internet browser can be recognized and identified using the unique cookie ID.

Through the use of cookies, the Herzschrittmacher für Ostafrika e.V. can provide the users of this website with more user-friendly services that would not be possible without the cookie setting.

By means of a cookie, the information and offers on our website can be optimized with the user in mind. Cookies allow us, as previously mentioned, to recognize our website users. The purpose of this recognition is to make it easier for users to utilize our website. The website user that uses cookies, e.g. does not have to enter access data each time the website is accessed, because this is taken over by the website, and the cookie is thus stored on the users computer system. Another example is the cookie of a shopping cart in an online shop. The online store remembers the articles that a customer has placed in the virtual shopping cart via a cookie.

The data subject may, at any time, prevent the setting of cookies through our website by means of a corresponding setting of the Internet browser used, and may thus permanently deny the setting of cookies. Furthermore, already set cookies may be deleted at any time via an Internet browser or other software programs. This is possible in all popular Internet browsers. If the data subject deactivates the setting of cookies in the Internet browser used, not all functions of our website may be entirely usable.

4. Collection of general data and information

The website of the Herzschrittmacher für Ostafrika e.V. collects a series of general data and information when a data subject or automated system calls up the website. This general data and information are stored in the server log files. Collected may be (1) the browser types and versions used, (2) the operating system used by the accessing system, (3) the website from which an accessing system reaches our website (so-called referrers), (4) the sub-websites, (5) the date and time of access to the Internet site, (6) an Internet protocol address (IP address), (7) the Internet service provider of the accessing system, and (8) any other similar data and information that may be used in the event of attacks on our information technology systems.

When using these general data and information, the Herzschrittmacher für Ostafrika e.V. does not draw any conclusions about the data subject. Rather, this information is needed to (1) deliver the content of our website correctly, (2) optimize the content of our website as well as its advertisement, (3) ensure the long-term viability of our information technology systems and website technology, and (4) provide law enforcement authorities with the information necessary for criminal prosecution in case of a cyber-attack. Therefore, the Herzschrittmacher für Ostafrika e.V. analyzes anonymously collected data and information statistically, with the aim of increasing the data protection and data security of our enterprise, and to ensure an optimal level of protection for the personal data we process. The anonymous data of the server log files are stored separately from all personal data provided by a data subject.

5. Contact possibility via the website

The website of the Herzschrittmacher für Ostafrika e.V. contains information that enables a quick electronic contact to our enterprise, as well as direct communication with us, which also includes a general address of the so-called electronic mail (e-mail address). If a data subject contacts the controller by e-mail or via a contact form, the personal data transmitted by the data subject are automatically stored. Such personal data transmitted on a voluntary basis by a data subject to the data controller are stored for the purpose of processing or contacting the data subject. There is no transfer of this personal data to third parties.

6. Routine erasure and blocking of personal data

The data controller shall process and store the personal data of the data subject only for the period necessary to achieve the purpose of storage, or as far as this is granted by the European legislator or other legislators in laws or regulations to which the controller is subject to.

If the storage purpose is not applicable, or if a storage period prescribed by the European legislator or another competent legislator expires, the personal data are routinely blocked or erased in accordance with legal requirements.

7. Rights of the data subject

a) Right of confirmation

Each data subject shall have the right granted by the European legislator to obtain from the controller the confirmation as to whether or not personal data concerning him or her are being processed. If a data subject wishes to avail himself of this right of confirmation, he or she may, at any time, contact any employee of the controller.

b) Right of access

Each data subject shall have the right granted by the European legislator to obtain from the controller free information about his or her personal data stored at any time and a copy of this information. Furthermore, the European directives and regulations grant the data subject access to the following information:

the purposes of the processing;

the categories of personal data concerned;

the recipients or categories of recipients to whom the personal data have been or will be disclosed, in particular recipients in third countries or international organisations;

where possible, the envisaged period for which the personal data will be stored, or, if not possible, the criteria used to determine that period;

the existence of the right to request from the controller rectification or erasure of personal data, or restriction of processing of personal data concerning the data subject, or to object to such processing;

the existence of the right to lodge a complaint with a supervisory authority;

where the personal data are not collected from the data subject, any available information as to their source;

the existence of automated decision-making, including profiling, referred to in Article 22(1) and (4) of the GDPR and, at least in those cases, meaningful information about the logic involved, as well as the significance and envisaged consequences of such processing for the data subject.

Furthermore, the data subject shall have a right to obtain information as to whether personal data are transferred to a third country or to an international organisation. Where this is the case, the data subject shall have the right to be informed of the appropriate safeguards relating to the transfer.

If a data subject wishes to avail himself of this right of access, he or she may, at any time, contact any employee of the controller.

c) Right to rectification

Each data subject shall have the right granted by the European legislator to obtain from the controller without undue delay the rectification of inaccurate personal data concerning him or her. Taking into account the purposes of the processing, the data subject shall have the right to have incomplete personal data completed, including by means of providing a supplementary statement.

If a data subject wishes to exercise this right to rectification, he or she may, at any time, contact any employee of the controller.

d) Right to erasure (Right to be forgotten)

Each data subject shall have the right granted by the European legislator to obtain from the controller the erasure of personal data concerning him or her without undue delay, and the controller shall have the obligation to erase personal data without undue delay where one of the following grounds applies, as long as the processing is not necessary:

The personal data are no longer necessary in relation to the purposes for which they were collected or otherwise processed.

The data subject withdraws consent to which the processing is based according to point (a) of Article 6(1) of the GDPR, or point (a) of Article 9(2) of the GDPR, and where there is no other legal ground for the processing.

The data subject objects to the processing pursuant to Article 21(1) of the GDPR and there are no overriding legitimate grounds for the processing, or the data subject objects to the processing pursuant to Article 21(2) of the GDPR.

The personal data have been unlawfully processed.

The personal data must be erased for compliance with a legal obligation in Union or Member State law to which the controller is subject.

The personal data have been collected in relation to the offer of information society services referred to in Article 8(1) of the GDPR.

If one of the aforementioned reasons applies, and a data subject wishes to request the erasure of personal data stored by the Herzschrittmacher für Ostafrika e.V., he or she may, at any time, contact any employee of the controller. An employee of Herzschrittmacher für Ostafrika e.V. shall promptly ensure that the erasure request is complied with immediately.

Where the controller has made personal data public and is obliged pursuant to Article 17(1) to erase the personal data, the controller, taking account of available technology and the cost of implementation, shall take reasonable steps, including technical measures, to inform other controllers processing the personal data that the data subject has requested erasure by such controllers of any links to, or copy or replication of, those personal data, as far as processing is not required. An employees of the Herzschrittmacher für Ostafrika e.V. will arrange the necessary measures in individual cases.

e) Right of restriction of processing

Each data subject shall have the right granted by the European legislator to obtain from the controller restriction of processing where one of the following applies:

The accuracy of the personal data is contested by the data subject, for a period enabling the controller to verify the accuracy of the personal data.

The processing is unlawful and the data subject opposes the erasure of the personal data and requests instead the restriction of their use instead.

The controller no longer needs the personal data for the purposes of the processing, but they are required by the data subject for the establishment, exercise or defence of legal claims.

The data subject has objected to processing pursuant to Article 21(1) of the GDPR pending the verification whether the legitimate grounds of the controller override those of the data subject.

If one of the aforementioned conditions is met, and a data subject wishes to request the restriction of the processing of personal data stored by the Herzschrittmacher für Ostafrika e.V., he or she may at any time contact any employee of the controller. The employee of the Herzschrittmacher für Ostafrika e.V. will arrange the restriction of the processing.

f) Right to data portability

Each data subject shall have the right granted by the European legislator, to receive the personal data concerning him or her, which was provided to a controller, in a structured, commonly used and machine-readable format. He or she shall have the right to transmit those data to another controller without hindrance from the controller to which the personal data have been provided, as long as the processing is based on consent pursuant to point (a) of Article 6(1) of the GDPR or point (a) of Article 9(2) of the GDPR, or on a contract pursuant to point (b) of Article 6(1) of the GDPR, and the processing is carried out by automated means, as long as the processing is not necessary for the performance of a task carried out in the public interest or in the exercise of official authority vested in the controller.

Furthermore, in exercising his or her right to data portability pursuant to Article 20(1) of the GDPR, the data subject shall have the right to have personal data transmitted directly from one controller to another, where technically feasible and when doing so does not adversely affect the rights and freedoms of others.

In order to assert the right to data portability, the data subject may at any time contact any employee of the Herzschrittmacher für Ostafrika e.V..

g) Right to object

Each data subject shall have the right granted by the European legislator to object, on grounds relating to his or her particular situation, at any time, to processing of personal data concerning him or her, which is based on point (e) or (f) of Article 6(1) of the GDPR. This also applies to profiling based on these provisions.

The Herzschrittmacher für Ostafrika e.V. shall no longer process the personal data in the event of the objection, unless we can demonstrate compelling legitimate grounds for the processing which override the interests, rights and freedoms of the data subject, or for the establishment, exercise or defence of legal claims.

If the Herzschrittmacher für Ostafrika e.V. processes personal data for direct marketing purposes, the data subject shall have the right to object at any time to processing of personal data concerning him or her for such marketing. This applies to profiling to the extent that it is related to such direct marketing. If the data subject objects to the Herzschrittmacher für Ostafrika e.V. to the processing for direct marketing purposes, the Herzschrittmacher für Ostafrika e.V. will no longer process the personal data for these purposes.

In addition, the data subject has the right, on grounds relating to his or her particular situation, to object to processing of personal data concerning him or her by the Herzschrittmacher für Ostafrika e.V. for scientific or historical research purposes, or for statistical purposes pursuant to Article 89(1) of the GDPR, unless the processing is necessary for the performance of a task carried out for reasons of public interest.

In order to exercise the right to object, the data subject may contact any employee of the Herzschrittmacher für Ostafrika e.V.. In addition, the data subject is free in the context of the use of information society services, and notwithstanding Directive 2002/58/EC, to use his or her right to object by automated means using technical specifications.

h) Automated individual decision-making, including profiling

Each data subject shall have the right granted by the European legislator not to be subject to a decision based solely on automated processing, including profiling, which produces legal effects concerning him or her, or similarly significantly affects him or her, as long as the decision (1) is not is necessary for entering into, or the performance of, a contract between the data subject and a data controller, or (2) is not authorised by Union or Member State law to which the controller is subject and which also lays down suitable measures to safeguard the data subjects rights and freedoms and legitimate interests, or (3) is not based on the data subjects explicit consent.

If the decision (1) is necessary for entering into, or the performance of, a contract between the data subject and a data controller, or (2) it is based on the data subjects explicit consent, the Herzschrittmacher für Ostafrika e.V. shall implement suitable measures to safeguard the data subjects rights and freedoms and legitimate interests, at least the right to obtain human intervention on the part of the controller, to express his or her point of view and contest the decision.

If the data subject wishes to exercise the rights concerning automated individual decision-making, he or she may, at any time, contact any employee of the Herzschrittmacher für Ostafrika e.V..

i) Right to withdraw data protection consent

Each data subject shall have the right granted by the European legislator to withdraw his or her consent to processing of his or her personal data at any time.

If the data subject wishes to exercise the right to withdraw the consent, he or she may, at any time, contact any employee of the Herzschrittmacher für Ostafrika e.V..

8. Legal basis for the processing

Art. 6(1) lit. a GDPR serves as the legal basis for processing operations for which we obtain consent for a specific processing purpose. If the processing of personal data is necessary for the performance of a contract to which the data subject is party, as is the case, for example, when processing operations are necessary for the supply of goods or to provide any other service, the processing is based on Article 6(1) lit. b GDPR. The same applies to such processing operations which are necessary for carrying out pre-contractual measures, for example in the case of inquiries concerning our products or services. Is our company subject to a legal obligation by which processing of personal data is required, such as for the fulfillment of tax obligations, the processing is based on Art. 6(1) lit. c GDPR. In rare cases, the processing of personal data may be necessary to protect the vital interests of the data subject or of another natural person. This would be the case, for example, if a visitor were injured in our company and his name, age, health insurance data or other vital information would have to be passed on to a doctor, hospital or other third party. Then the processing would be based on Art. 6(1) lit. d GDPR. Finally, processing operations could be based on Article 6(1) lit. f GDPR. This legal basis is used for processing operations which are not covered by any of the abovementioned legal grounds, if processing is necessary for the purposes of the legitimate interests pursued by our company or by a third party, except where such interests are overridden by the interests or fundamental rights and freedoms of the data subject which require protection of personal data. Such processing operations are particularly permissible because they have been specifically mentioned by the European legislator. He considered that a legitimate interest could be assumed if the data subject is a client of the controller (Recital 47 Sentence 2 GDPR).

9. The legitimate interests pursued by the controller or by a third party

Where the processing of personal data is based on Article 6(1) lit. f GDPR our legitimate interest is to carry out our business in favor of the well-being of all our employees and the shareholders.

10. Period for which the personal data will be stored

The criteria used to determine the period of storage of personal data is the respective statutory retention period. After expiration of that period, the corresponding data is routinely deleted, as long as it is no longer necessary for the fulfillment of the contract or the initiation of a contract.

11. Provision of personal data as statutory or contractual requirement; Requirement necessary to enter into a contract; Obligation of the data subject to provide the personal data; possible consequences of failure to provide such data

We clarify that the provision of personal data is partly required by law (e.g. tax regulations) or can also result from contractual provisions (e.g. information on the contractual partner). Sometimes it may be necessary to conclude a contract that the data subject provides us with personal data, which must subsequently be processed by us. The data subject is, for example, obliged to provide us with personal data when our company signs a contract with him or her. The non-provision of the personal data would have the consequence that the contract with the data subject could not be concluded. Before personal data is provided by the data subject, the data subject must contact any employee. The employee clarifies to the data subject whether the provision of the personal data is required by law or contract or is necessary for the conclusion of the contract, whether there is an obligation to provide the personal data and the consequences of non-provision of the personal data.

12. Existence of automated decision-making

As a responsible company, we do not use automatic decision-making or profiling.

This Privacy Policy has been generated by the Privacy Policy Generator of the External Data Protection Officers that was developed in cooperation with the Media Law Lawyers from WBS-LAW.

Why do African-Americans face higher risk of heart disease? | Heart

When I see one of my heart patients, I keep in mind that this individual is part of a family, part of a community.

As a community, African-Americans have higher rates of high blood pressure, high cholesterol, obesity, and diabetes – the four major risk factors for heart disease. For instance, 57 percent of adult African-American women are obese, compared to 34 percent of non-Hispanic white women, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Teasing out the reasons for these risk factor differences is difficult. If everyone in a family has high blood pressure, does that mean it’s genetic, or does that mean everyone in the family is leading a similar lifestyle?

Certainly, genetics appears to play some role. Some studies suggest that African-Americans are particularly sensitive to salt, which can lead to high blood pressure. But much of the difference is likely lifestyle, which is influenced by a variety of elements, including socioeconomic status, education, environment, stress levels, culture, and history.

As an example of how history can affect health, let’s focus on weight for a second. Research from UT Southwestern has shown that many people in the African-American community, particularly older individuals, believe that a heavier weight is a healthier weight. Historically, there were good reasons to believe this. Having extra weight could feasibly offer protection against things people used to be susceptible to, such as infectious disease and not having enough food.

But we Americans aren’t dying excessively from infectious diseases these days. Now we’re dying of heart disease, and we need to change our perception of what healthy looks like – literally.

Role of economics, stress

Economics and stress levels often play a role in high blood pressure. Fresh fruits and vegetables may not be readily available to those with limited access, and it takes time, money, and resources to lead a healthy lifestyle. Additionally, prepackaged foods and fast foods are filled with excessive salt, which adds to the difficulty of controlling blood pressure. Unfortunately, this usually means it will take multiple medications to achieve adequate control.

Cultural norms can affect even how we exercise. Building up your biceps does not help protect your heart. Although resistance training is important, exercise should be cardiovascular. You’ve got to be able to walk a mile, run a mile.

If you are an African-American and heart disease runs in your family, I urge you to see a general physician or preventive cardiologist in your 20s to discuss a healthy weight for you, to make sure your blood pressure levels are normal, and to make a plan for healthy eating and exercising.

To request an appointment at UT Southwestern, please fill out and submit the Request an Appointment form or call 214-645-8300.

Why Are African-Americans at Greater Risk for Heart Disease?

Heart disease has haunted generations of Robin Drummond’s family. “I have a

family history of

heart disease on both sides,” says the 55-year-old African-American and

resident of Hammond, La. “I’ve had uncles, aunts, and grandparents who’ve died

from

heart attacks and heart disease, and two of my mother’s brothers died four

months apart. One had a heart attack in church, and four months later, one had

a heart attack in the post office.”

When Drummond’s father succumbed to heart disease at age 50,

she was shaken. “Particularly when my dad died, I wanted to make sure that I

was OK,” she says. In 2002, she went to her doctor for testing and learned that

her heart was mildly enlarged, placing her at risk for

heart failure. Drummond, a registered dietitian, took strenuous measures to

ward off trouble. But not all African-Americans are aware of the danger.

African-Americans and Heart Failure

In a startling 2009 study published in the New England

Journal of Medicine, researchers found that African-Americans have a much

higher incidence of heart failure than other races, and it develops at younger

ages. Heart failure means that the heart isn’t able to pump blood as well as it

should.

Before age 50, African-Americans’ heart failure rate is 20

times higher than that of whites, according to the study. Four risk factors are

the strongest predictors of heart failure:

high blood pressure (also called hypertension), chronic

kidney disease, being

overweight, and having low levels of HDL, the “good”

cholesterol. Three-fourths of African-Americans who develop heart failure

have high

blood pressure by age 40.

African-Americans and Health Care

To prevent heart failure and other heart disease, it’s crucial

to treat risk factors successfully, says Anne L. Taylor, MD, a professor of

medicine at New York Presbyterian Hospital and vice dean of academic affairs at

Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons. But, compared with

their white peers, African-Americans often have less access to health care, she

says. Not only are they less likely to visit a doctor and get routine

screenings, but they’re less likely to be referred to specialists.

“African-Americans with heart failure are more likely to be

taken care of in a primary care practice,” Taylor says, “even though the data

would suggest that the best care — the care that decreases hospitalizations

and improves mortality rates — happens in cardiologists’ offices.”

Further, some African-Americans “tend to see illness and disease as the main

reason for health care, so you don’t go to the physician for preventive

medicine — you go when you’re sick,” says Keith C. Ferdinand, MD, FACC, FAHA.

Ferdinand is a clinical professor in the cardiology division at Emory

University and chief science officer of the Association of Black Cardiologists.

“When are you sick? When you have symptoms:

chest pain, shortness of breath, swelling,

dizziness. By the time people manifest the signs and symptoms of

cardiovascular disease, they have already had that disease present for one,

two, or even three decades.”

Treating Heart Disease Risk Factors

Drummond’s father, who had health insurance but not a physician

he would go to on a regular basis, provides a cautionary tale about why

African-Americans must maintain a consistent relationship with a good doctor

who knows their medical history and provides preventive care, screenings, and

referrals to specialists.

“He had a leaking valve, and it didn’t get replaced as soon as

it should have,” Drummond says. “The doctor told us it should have been

replaced six or seven years earlier. When he started having swelling in his

legs and shortness of breath, that’s when he went to the hospital.” Doctors

diagnosed the leaking valve and performed surgery, but “it was too late for

him,” Drummond says. He died a few weeks after his surgery.

Besides a strong family history, Drummond has other risk

factors for heart disease. She was diagnosed with high blood pressure at age 28

and with

type 2 diabetes about five years ago. After years of unsuccessfully trying

to control her blood pressure with diet and

exercise, she now takes medications.

She’s under a doctor’s regular care, and she stays fit and eats

healthy foods. “I work hard. I go to the gym to help control my hypertension

and

diabetes. I take the meds, I watch my sodium intake, and I work at keeping

my

weight within normal range.” So far, she says, she’s avoided heart

failure.

What to Ask Your Doctor About Heart Disease

High blood pressure is a major risk factor for heart failure.

Work with your doctor to keep it in check by asking the following

questions:

- What is my risk for developing high blood pressure?

- How can I limit my risk and help prevent it?

- What are the symptoms?

- What does my blood pressure reading actually mean?

- Am I taking any medicines that make me more susceptible?

- What medications are available if I have high blood pressure?

- What are the benefits and side effects?

African Americans and Heart Disease, Stroke

Heart disease is the No. 1 killer for all Americans, and stroke is also a leading cause of death. As frightening as those statistics are the risks of getting those diseases are even higher for African-Americans.

The good news is, African-Americans can improve their odds of preventing and beating these diseases by understanding the risks and taking simple steps to address them.

“Get checked, then work with your medical professional on your specific risk factors and the things that you need to do to take care of your personal health,” said Winston Gandy, M.D., a cardiologist and chief medical marketing officer with the Piedmont Heart Institute in Atlanta and a volunteer with the American Heart Association.

High blood pressure, overweight and obesity and diabetes are common conditions that increase the risk of heart disease and stroke. Here’s how they affect African-Americans and some tips to lower your risk.

High Blood Pressure

The prevalence of high blood pressure in African-Americans is the highest in the world. Also known as hypertension, high blood pressure increases your risk of heart disease and stroke, and it can cause permanent damage to the heart before you even notice any symptoms, that’s why it is often referred to as the “silent killer.” Not only is HBP more severe in blacks than whites, but it also develops earlier in life.

Your healthcare provider can help you find the right medication, and lifestyle changes can also have a big impact.

“You can’t do anything about your family history, but you can control your blood pressure,” Dr. Gandy said.

If you know your blood pressure is high, keeping track of changes is important. Check it regularly, and notify your doctor of changes in case treatment needs to be adjusted, Dr. Gandy said. Even if you don’t have high blood pressure, he recommends checking it every two years.

“The No. 1 thing you can do is check your blood pressure regularly,” he said.

Obesity