How does the Double Fisherman’s Knot work. What are the key steps to tying a Double Fisherman’s Knot correctly. Why is the Double Fisherman’s Knot considered one of the strongest and most secure knots for joining two ropes. When should climbers use a Double Fisherman’s Knot versus other rope-joining methods.

Understanding the Double Fisherman’s Knot: Purpose and Applications

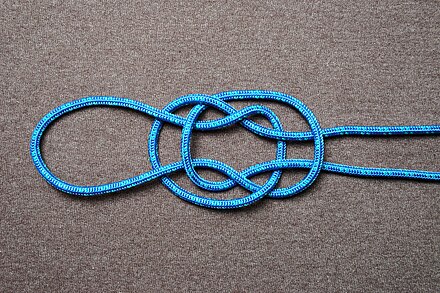

The Double Fisherman’s Knot, also known as a grapevine knot, is a highly secure method for joining two ropes or cord ends together. This knot is particularly favored in rock climbing and mountaineering due to its exceptional strength and reliability under high loads.

But what makes this knot so special? The Double Fisherman’s Knot creates an incredibly strong connection between two ropes, even those of different diameters. Its interlocking structure distributes force evenly, reducing the risk of slippage or failure under tension.

Key Applications of the Double Fisherman’s Knot

- Joining two climbing ropes for long rappels

- Creating cordage loops for anchors or prussik hitches

- Repairing damaged ropes in emergency situations

- Connecting accessory cords of different sizes

While the Double Fisherman’s Knot excels in strength, it’s important to note that it can be challenging to untie after heavy loading. This characteristic makes it less suitable for temporary connections or situations where quick release might be necessary.

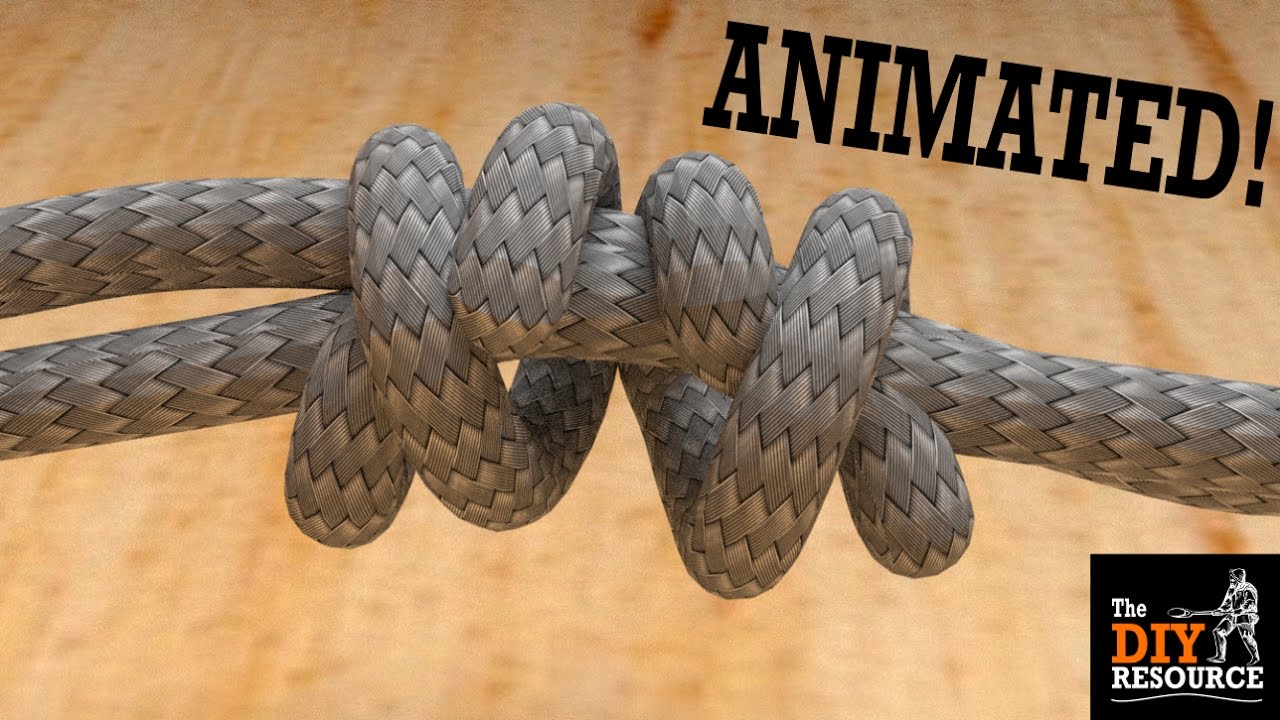

Step-by-Step Guide: How to Tie a Double Fisherman’s Knot

Mastering the Double Fisherman’s Knot is a valuable skill for any climber or outdoor enthusiast. Follow these steps to tie this essential knot:

- Lay the two rope ends parallel to each other, facing opposite directions.

- Take the working end of one rope and create a small loop around the standing end of the other rope.

- Wrap the working end around both ropes twice, passing through the small loop on the final wrap.

- Pull the working end to tighten, creating a neat barrel shape.

- Repeat steps 2-4 with the other rope’s working end, creating a mirror image of the first knot.

- Slowly tighten both knots by pulling on the standing ends of each rope.

- Adjust the knots so they sit close together, forming the complete Double Fisherman’s Knot.

Practice tying this knot repeatedly until you can perform it confidently and efficiently. Remember, in climbing situations, your life may depend on the integrity of your knots.

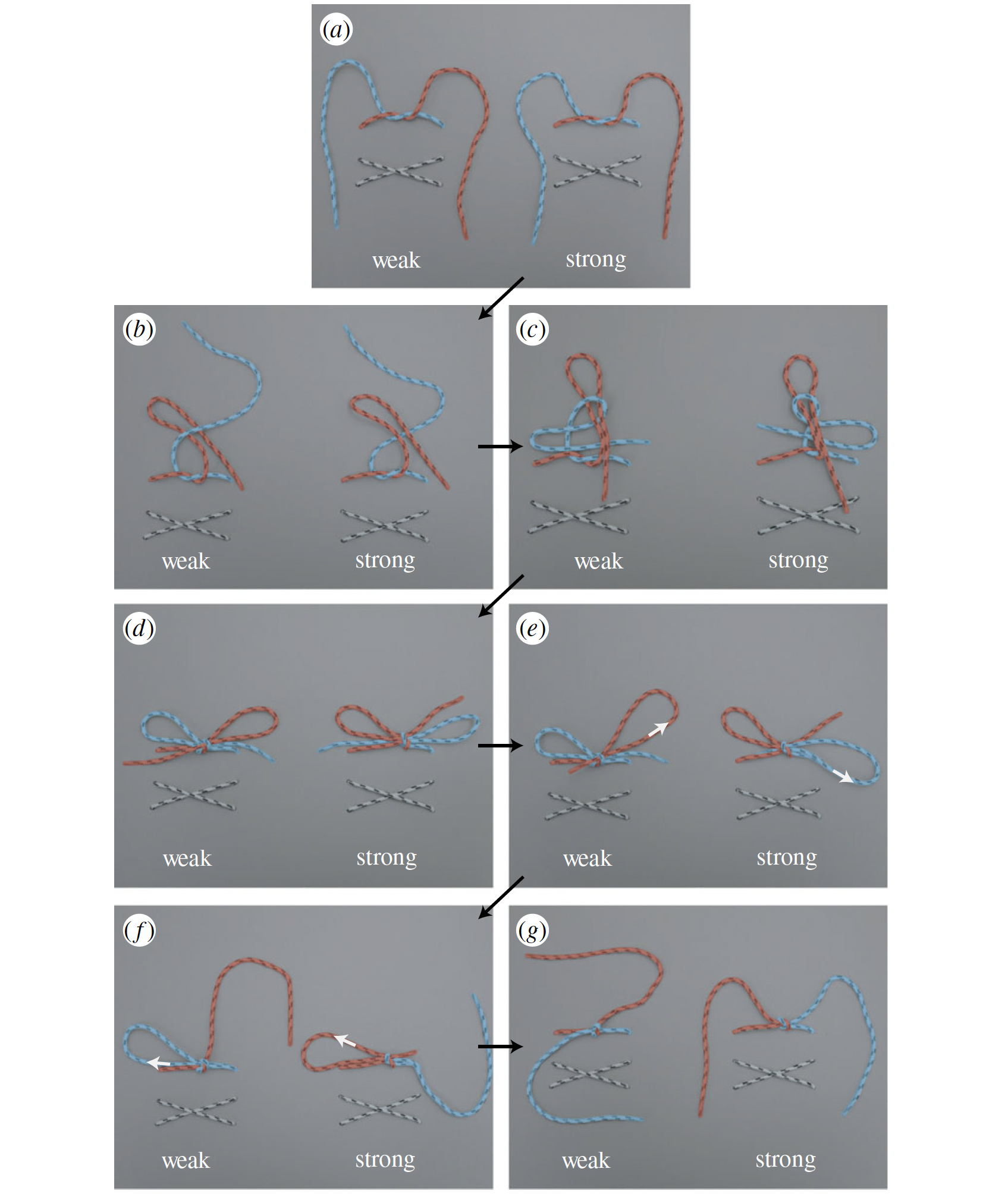

The Science Behind the Double Fisherman’s Knot’s Strength

The Double Fisherman’s Knot’s remarkable strength comes from its unique structure and mechanics. But what exactly makes it so robust?

The knot’s strength lies in its interlocking nature. As tension increases, the two separate knots cinch tighter against each other, creating a secure bind. This self-tightening property ensures that the knot becomes stronger under load, rather than weakening or slipping.

Additionally, the multiple wraps in each half of the knot distribute force across a larger surface area. This distribution helps prevent localized stress points that could lead to rope failure.

Strength Testing and Comparisons

In controlled tests, the Double Fisherman’s Knot has been shown to retain up to 65-70% of the rope’s original breaking strength. This impressive figure surpasses many other common joining knots, including:

- The Figure-8 Bend (retains approximately 60-65% strength)

- The Overhand Bend (retains only 50-55% strength)

- The Sheet Bend (retains about 55-60% strength)

These statistics highlight why the Double Fisherman’s Knot is often the preferred choice for critical rope connections in climbing and rescue scenarios.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Even experienced climbers can make errors when tying the Double Fisherman’s Knot. Recognizing and avoiding these mistakes is crucial for safety.

Insufficient Tightening

One of the most common errors is failing to tighten the knot adequately. A loose Double Fisherman’s Knot can slip under load, compromising its strength and reliability.

To avoid this, ensure you pull each working end firmly when forming the initial knots. Then, gradually tighten the entire structure by pulling on the standing ends of both ropes. The finished knot should be compact and uniform in appearance.

Incorrect Wrap Count

Using too few wraps can significantly weaken the knot. While a single-wrap version (known as the Single Fisherman’s Knot) exists, it’s not recommended for critical applications.

Always use at least two complete wraps for each half of the knot. Some climbers prefer three wraps for added security, especially with slippery synthetic ropes.

Misaligned Knots

The two halves of the Double Fisherman’s Knot should sit closely together, with their barrels aligned. Misalignment can create uneven loading and potential weak points.

Take care to position the knots correctly as you tighten them. Gently work the structure into proper alignment before applying full tension.

When to Use the Double Fisherman’s Knot (and When Not To)

While the Double Fisherman’s Knot is incredibly strong, it’s not always the best choice for every situation. Understanding when to use this knot – and when to opt for alternatives – is a key aspect of safe climbing and rope work.

Ideal Scenarios for the Double Fisherman’s Knot

- Creating permanent or semi-permanent cord loops for anchors or prusik hitches

- Joining ropes for extended rappels where maximum strength is crucial

- Connecting accessory cords of different diameters

- Any situation where the knot will be subjected to high loads or prolonged use

Situations to Consider Alternatives

- When quick release may be necessary (consider a Figure-8 Bend instead)

- For temporary connections that will be frequently tied and untied

- In scenarios where bulky knots could interfere with equipment or movement

- When working with exceptionally stiff or slippery ropes that may not hold the knot well

Always assess the specific requirements of your climbing or rigging situation before choosing a knot. While the Double Fisherman’s Knot excels in many areas, it’s essential to have a diverse repertoire of knots at your disposal.

Maintaining and Inspecting Your Double Fisherman’s Knot

Proper maintenance and regular inspection of your Double Fisherman’s Knot are crucial for ensuring its continued reliability and safety. But what specific steps should you take to keep this knot in top condition?

Regular Inspection Routine

- Visually examine the knot for any signs of wear, fraying, or distortion.

- Check that both halves of the knot remain tightly cinched and properly aligned.

- Inspect the rope on either side of the knot for any damage or weakening.

- Gently manipulate the knot, ensuring it hasn’t become overly stiff or difficult to adjust.

Perform these checks before each use of the rope, and more frequently if the knot has been subjected to heavy loads or harsh conditions.

Addressing Common Issues

If you notice any of the following problems, take immediate action to address them:

- Loose or misaligned knots: Carefully retighten and realign the knot structure.

- Frayed or damaged rope fibers: Consider cutting out the damaged section and retying the knot, or replacing the rope entirely if damage is extensive.

- Extreme difficulty in manipulating the knot: This may indicate that the knot has been overstressed. Untie it completely, inspect the rope thoroughly, and retie if the rope is still in good condition.

Remember, a well-maintained Double Fisherman’s Knot can provide years of reliable service, but safety should always be your top priority. When in doubt, err on the side of caution and replace questionable gear.

Advanced Techniques and Variations

While the standard Double Fisherman’s Knot is highly effective, there are several variations and advanced techniques that climbers and riggers should be aware of. These modifications can enhance the knot’s performance in specific situations or address particular challenges.

The Triple Fisherman’s Knot

This variation adds an extra wrap to each half of the knot, resulting in three complete turns instead of two. The Triple Fisherman’s Knot offers even greater security, especially when used with slippery synthetic ropes or in critical load-bearing applications.

To tie a Triple Fisherman’s Knot, simply follow the standard tying process but make three wraps instead of two before passing the working end through the initial loop.

The Asymmetrical Fisherman’s Knot

When joining ropes of significantly different diameters, an asymmetrical approach can be beneficial. This technique involves using more wraps on the thinner rope to compensate for the diameter difference.

For example, when joining an 8mm accessory cord to an 11mm climbing rope, you might use three wraps on the thinner cord and two on the thicker rope.

The Sliding Double Fisherman’s

This interesting variation creates an adjustable loop, similar to a prusik hitch. It’s formed by tying a standard Double Fisherman’s Knot but leaving one of the standing ends much longer. This longer end can then be pulled to adjust the size of the loop.

The Sliding Double Fisherman’s can be useful for creating adjustable anchors or improvised harnesses in emergency situations. However, it requires careful management to prevent accidental loosening.

Considerations for Advanced Techniques

While these variations can be incredibly useful, it’s important to understand their specific applications and limitations. Practice these techniques in controlled, low-stakes environments before relying on them in critical situations.

Always consider factors such as rope material, expected loads, and environmental conditions when choosing a knot variation. When in doubt, consult with more experienced climbers or professional riggers for guidance.

The Double Fisherman’s Knot in Modern Climbing

As climbing technology and techniques continue to evolve, how does the Double Fisherman’s Knot fit into modern climbing practices? This traditional knot remains a cornerstone of safe climbing, but its applications have adapted to suit contemporary needs and equipment.

Integration with New Gear

Modern climbing gear often incorporates high-tech materials and innovative designs. The Double Fisherman’s Knot has proven its versatility by adapting well to these advancements:

- Dyneema and Spectra Slings: The knot’s gripping power works effectively with these ultra-strong, low-stretch materials.

- Skinny Ropes: As climbing ropes trend thinner for weight savings, the Double Fisherman’s provides crucial strength for joining these slender cords.

- Static Line Rigging: In complex rigging scenarios for big wall climbing or caving, the knot’s reliability is invaluable.

Evolving Best Practices

While the basic structure of the Double Fisherman’s Knot remains unchanged, modern climbing has influenced how and when it’s used:

- Increased emphasis on redundancy in anchor building often incorporates the knot for creating backup loops.

- Growing popularity of multi-pitch rappelling has made proficiency with the Double Fisherman’s even more critical for safely joining ropes.

- Advanced rescue techniques often rely on the knot’s strength for creating improvised hauling systems or escape lines.

Education and Training

As climbing continues to gain popularity, proper education on knot tying, including the Double Fisherman’s, has become increasingly emphasized in introductory courses and certifications. Many climbing gyms and outdoor programs now include specific instruction on this knot as part of their basic safety curriculum.

Future Outlook

Looking ahead, the Double Fisherman’s Knot is likely to remain a crucial skill for climbers. Its simplicity, strength, and versatility ensure its relevance even as equipment and techniques continue to evolve. However, ongoing research into knot mechanics and new synthetic materials may lead to further refinements or specialized applications of this time-tested connection.

Ultimately, the Double Fisherman’s Knot serves as a prime example of how traditional climbing knowledge continues to complement and enhance modern practices, creating a safer and more capable climbing community.

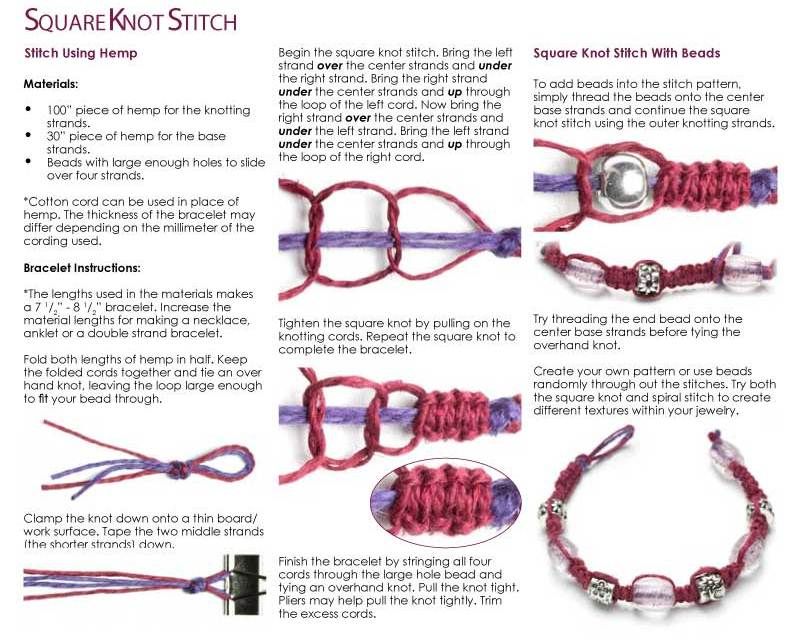

How to Tie Knots: Tying Different Types of Knots with Illustrations

Spend any time in Scouts, camping outdoors, or boating? From square knots to bowline, learn how to tie knots in rope, including illustrations of the most useful knots.

These knots will often come in handy outdoors. Better to know a knot just in case you need it!

Tying Knots: Words to Know

Before you get started learning this handy skill, it helps to know some of the basic knot vocabulary.

Learn How to Crochet: Easy Scarf for Beginners

3 Thrifty Ways to Protect Plants From Cold

How to Build a Hoop House

- The bight is any part of a rope between the ends or the curved section of a rope in a knot.

- A bight becomes a loop when two parts of a rope cross.

- The place at which two parts of a rope meet in a loop is the crossing point.

- The place at which two or more loops bend is the elbow.

- The working end of a rope is the end being used to make a knot.

- The standing end (or standing part) of a rope is the end not involved in making a knot.

8 Useful Knots to Know

The knot illustrations below may seem a bit intimidating at first, but once you know the vocabulary and practice a few times, we’re sure you’ll be able to get it! Note: Illustrations by Lars Poyansky.

1. Square Knot

A square knot is a quick and simple way to join two ropes together. However, it’s for light use, not heavy use, such as tying scarves, package parcels, and so forth. The rope will not hold under heavy strain.

Watch video to see how to tie the Square Knot:

2. A Half Hitch

A hitch is used to tie a rope around an object (such as a tree) and back to itself. It’s for a quick temporary use, not long-term.

It’s for a quick temporary use, not long-term.

3. Two Half Hitches

This knot is also used to secure an object to trees, loops, or poles. Once tied, the knot formed by two half-hitches can move along the rope, allowing the loop to become larger or smaller. However, this hitch also isn’t for heavy loads.

Watch this video to see how to tie Two Half Hitches:

4. Taut-Line Hitch

Somewhat similar to two half hitches, the taut-line hitch is also an adjustable loop-knot hitch that can be tied around bars or poles. However, the loop formed using a taut-line hitch will not slip if put under tension. A common use might be setting up a hammock or securing a load to a car to easily adjust the binding’s tightness.

Watch this video to see how to tie a Taut-Line Hitch:

youtube.com/embed/h5rbBHp1QXo” title=”YouTube video player”>

5. Sheet Bend

Like a square knot, a sheet bend joins two ropes. However, in this case, the knot can be used for heavy loads and won’t slip under heavy tension. In addition, it’s reliable when joining two ropes of different thickness, size, or material. A sheet bend could be used to attach two lines together to make a longer line or for securing a critical load in a vehicle. There’s also a Double Sheet Bend which takes an extra coil around the standing loop for better security (especially with plastic rope)

Watch this video to see how to tie the Sheet Bend Knot:

6. Bowline

When you need a non-slip loop at the end of a line, you go with a classic bowline. This fixed knot won’t slip, regardless of the load applied. It is also easy to untie. Bowlines are secure and used when you need to pull or rescue someone, or tie a line around yourself and a tree or other object.

This fixed knot won’t slip, regardless of the load applied. It is also easy to untie. Bowlines are secure and used when you need to pull or rescue someone, or tie a line around yourself and a tree or other object.

Watch this video to see how to tie the common Bowline:

7. Clove Hitch

Easy to tie and untie, the Clove Hitch is a good binding knot when you’re in a rush. They’re great for a temporary hold, e.g., attach a rope to a post or a linen to a mooring buoy. When you tighten this knot, you must pull both ends lengthwise or it won’t be secure.

Watch this video to see how to tie a Clove Hitch:

youtube.com/embed/Gs9WyrzNjJs” title=”YouTube video player”>

8. Timber Hitch

If you spend a lot of time outdoors, the Timber Hitch is a simple knot for hauling a log or bunches of branches as well as hauling away large objects. It’s easy to tie and remove but will come apart if tension is not maintained in the rope. Make three loops minimum to ensure a more secure hold.

Watch this video to see how to tie a Timber Hitch:

See more tips and tools to enjoy in the outdoors!

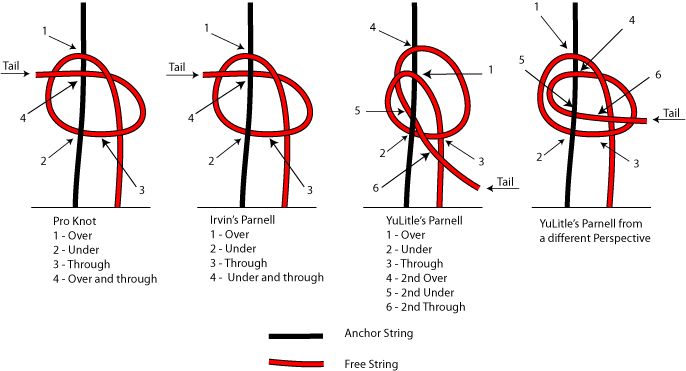

Rock Climbing Tech Tips: Joining Two Ropes

Joining Two

Ropes

This is a touchy subject. Opinions vary

among climbers as to the best knot to use when joining two ropes together.

The figure eight, overhand, & double fishersman’s are just three

methods. There’s many reasons why you’d want to join two ropes together, but

There’s many reasons why you’d want to join two ropes together, but

perhaps the most obvious one is to allow for a full rope length retrievable

abseil.

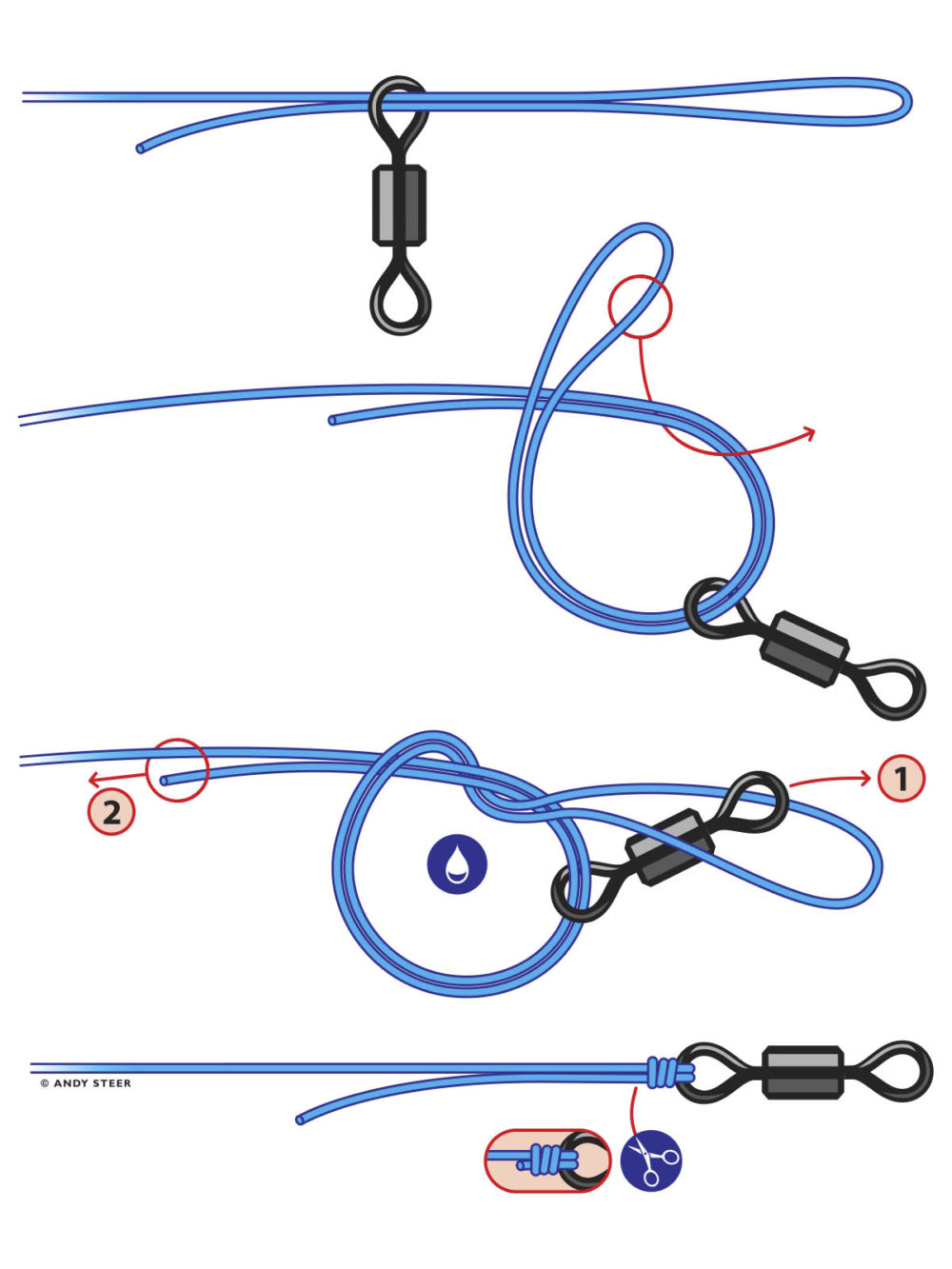

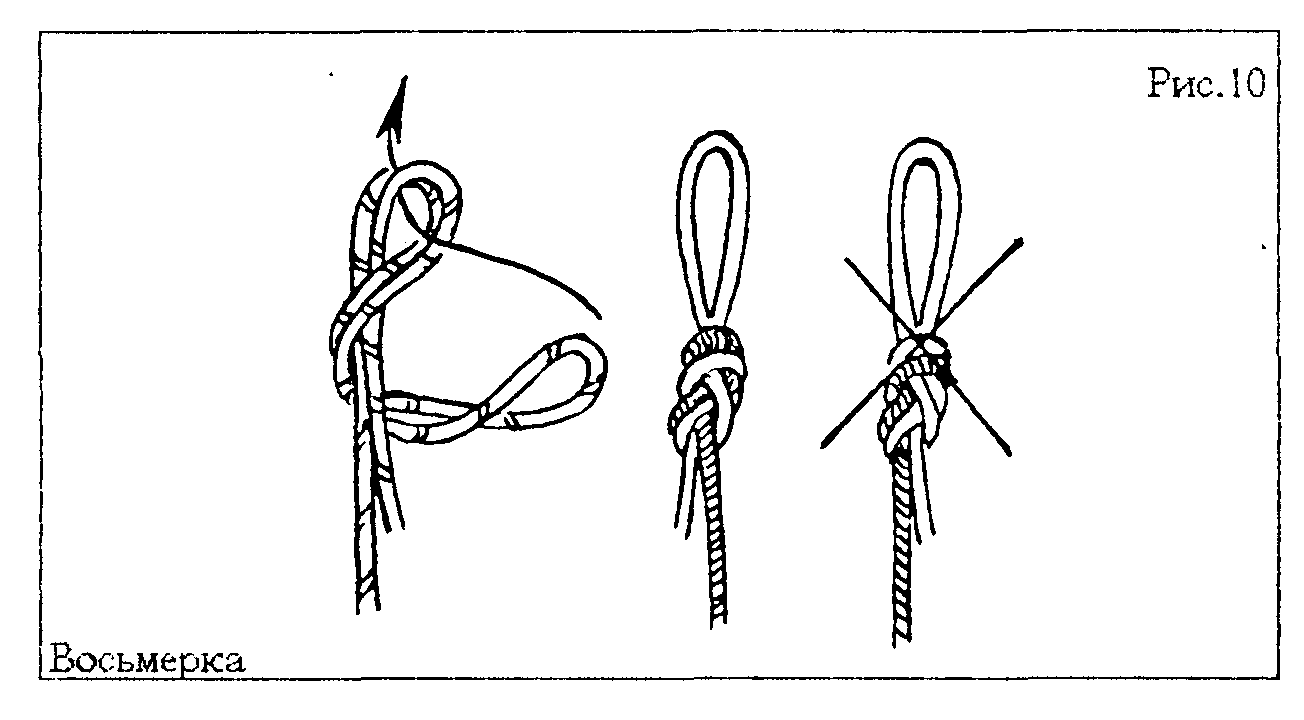

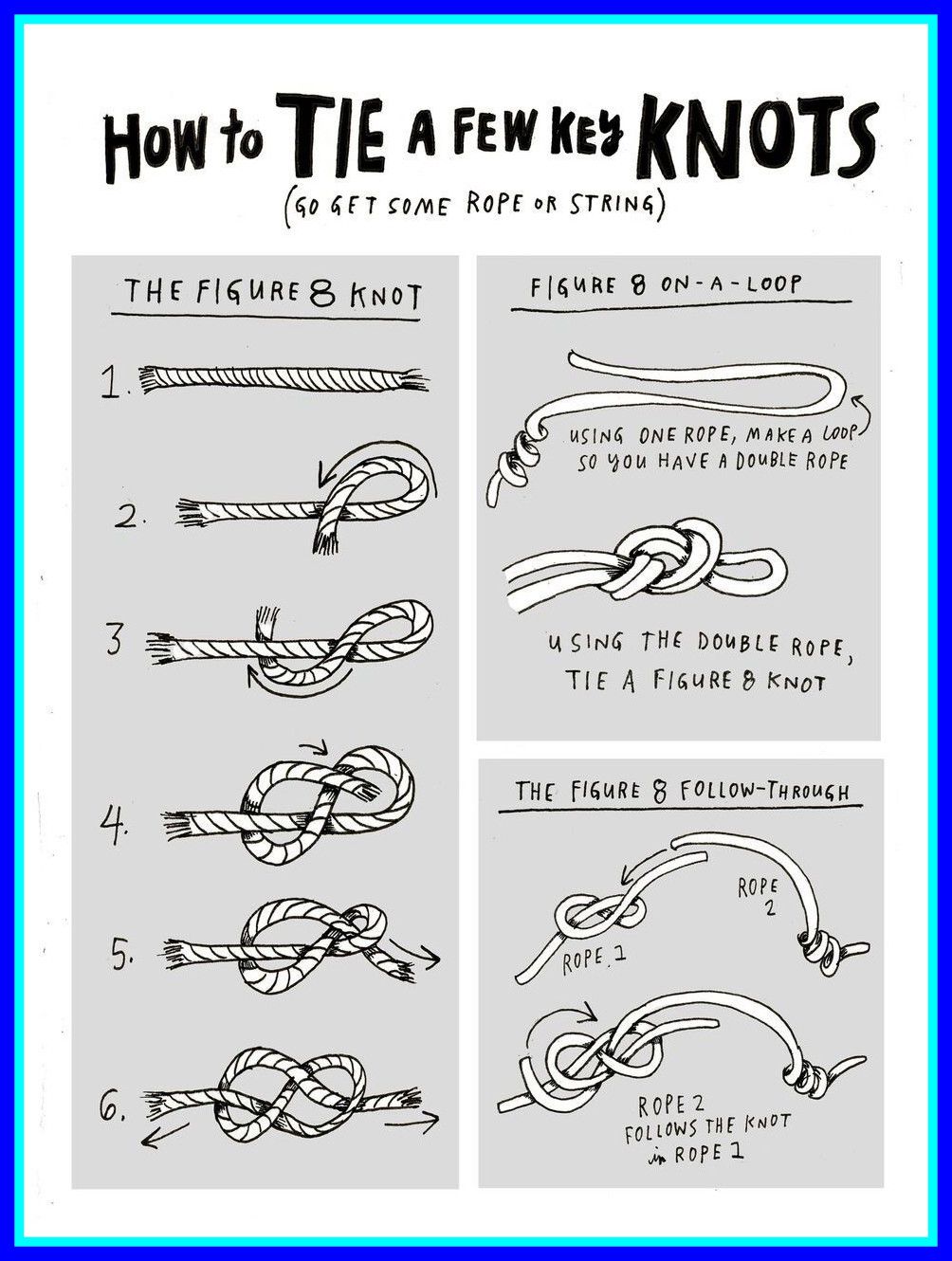

Rethreaded Figure Eight

There is more than one way of joining two ropes using a figure eight knot.

The method described below is purely the one I prefer. One disadvantage of

this method is that it leaves a bulky profile to the knot which could well get stuck when

you pull the abseil ropes down. If speed and stuck ropes is a concern, perhaps investigate the

double

fisherman’s

method or the overhand knot (see below). The

advantage of the figure eight with stopper knots over the double

fisherman’s is that it’s often easier to untie afterwards, plus what I’d

call a psychological advantage. Anyway, follow these steps to join two ropes with

a figure eight knot:

Step 1: Put a figure eight in the end of one rope. Step 2 & 3:

Step 2 & 3:

Rethread the

eight with the end of the other rope. Leave plenty of tail (probably more

than pictured), because the

knot will slip a bit as it is tightened.

Step 4: Because I’m paranoid

about the figure eight slipping I generally add a stopper knot

to each end

as well. The figure eight with stopper knots is my preferred method,

however as I say, opinions vary.

Note: Avoid

using the “Abnormal Figure Eight” (pictured left), which Bush Walkers Wilderness

Rescue’s research shows to

be dangerous. They state: “The Abnormal Figure 8 Knot

is dangerous due to roll back slippage. It is possible that this knot when

poorly packed and with short tails could completely

undo with loads as low as 50kgs”. See Also: Abseil

Knots on Needle Sports, and this accident

report on rec. climbing or

climbing or

R&I, in which such a knot may have killed a climber.

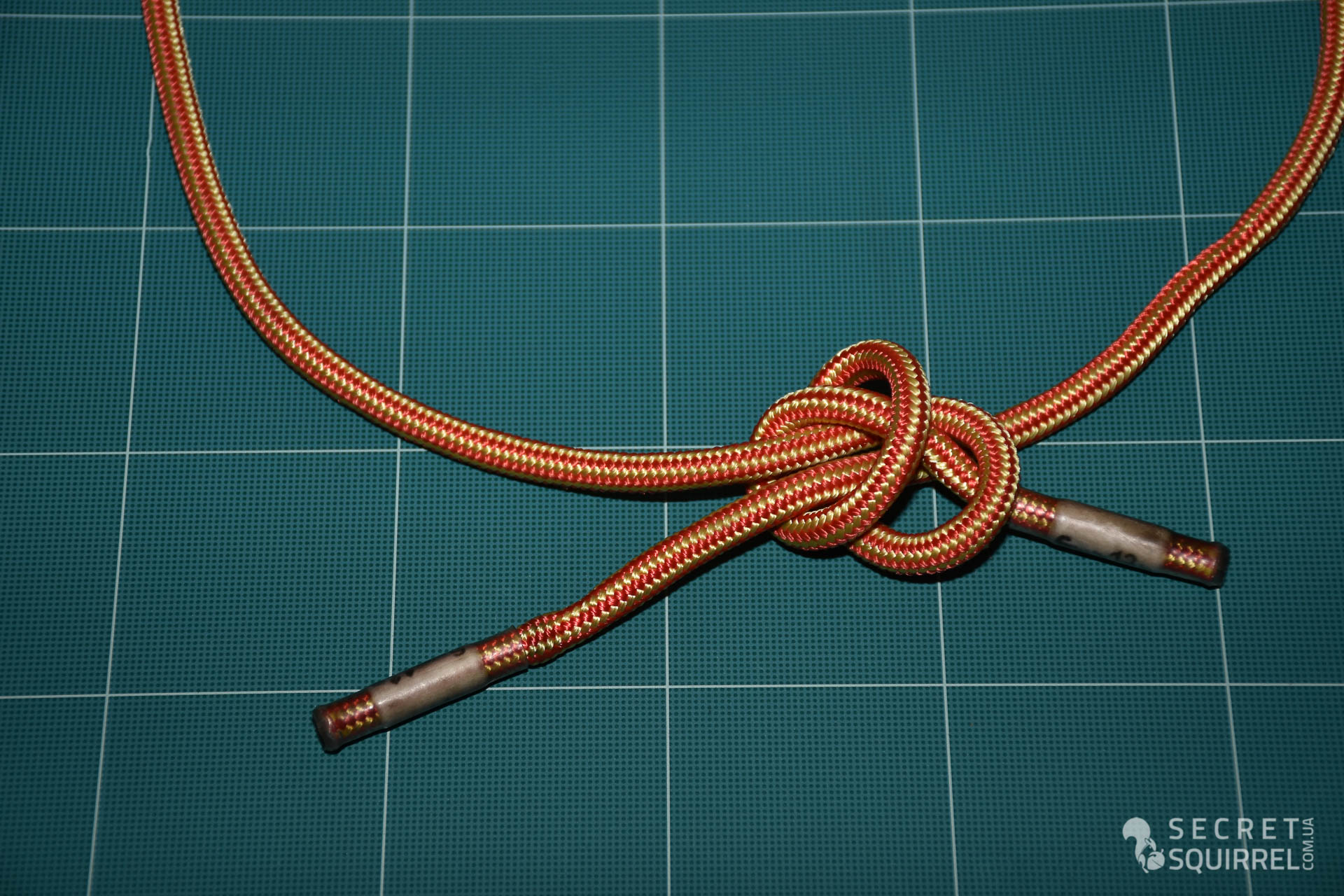

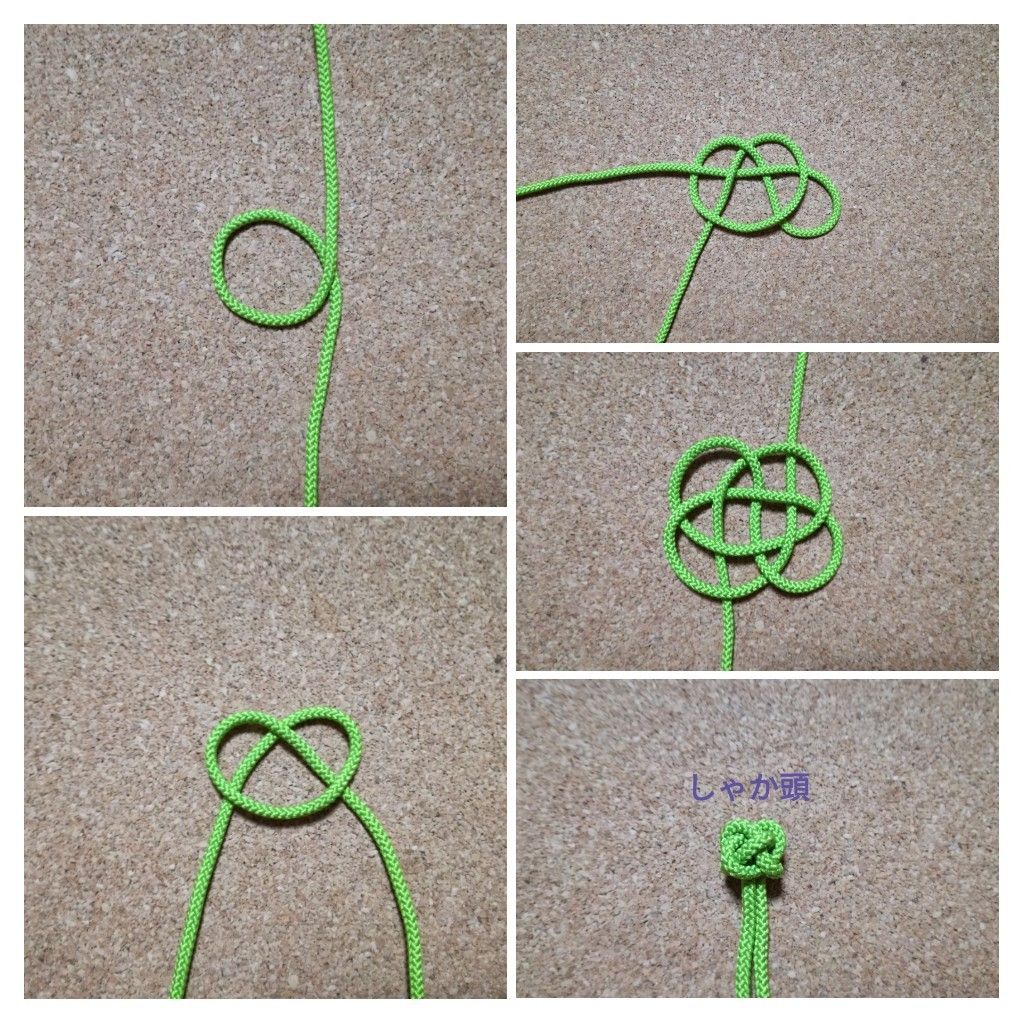

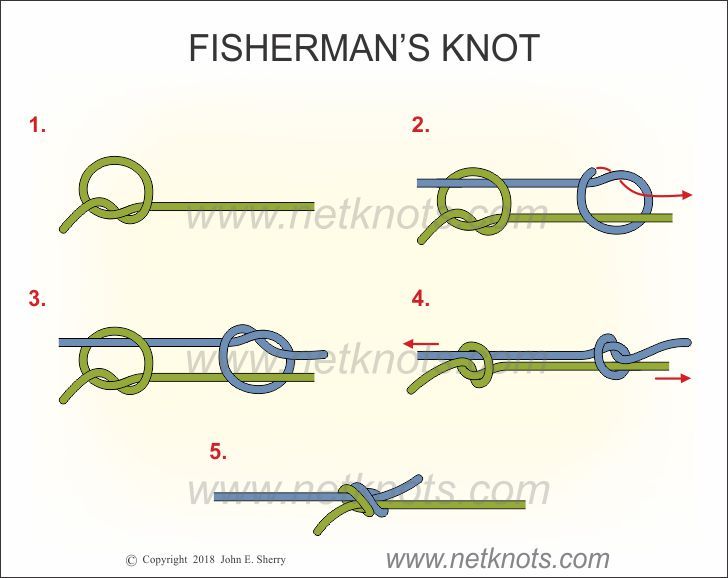

Double Fisherman’s

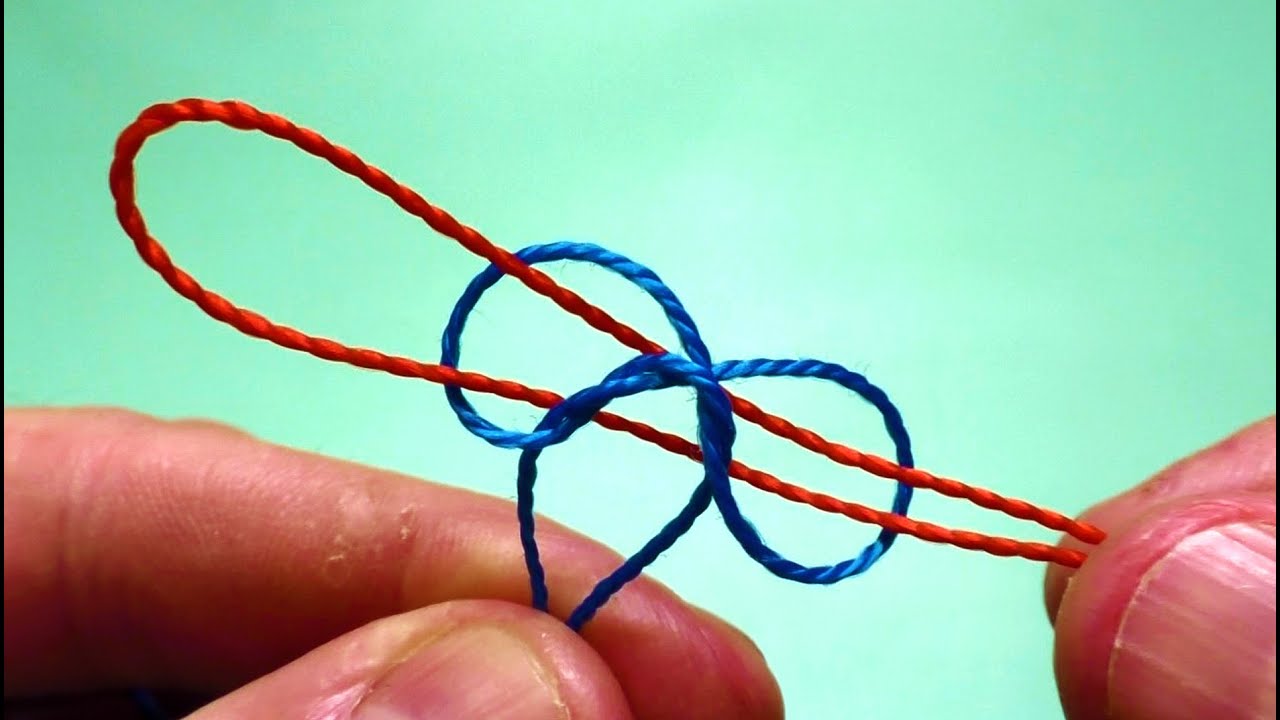

Here’s another way to join two ropes, the double fisherman’s (pictured

below). This method results in a smaller profile knot (should give less

chance of stuck ropes) than the aforementioned figure eight method. Its

basically just two stopper knots. Follow these steps:

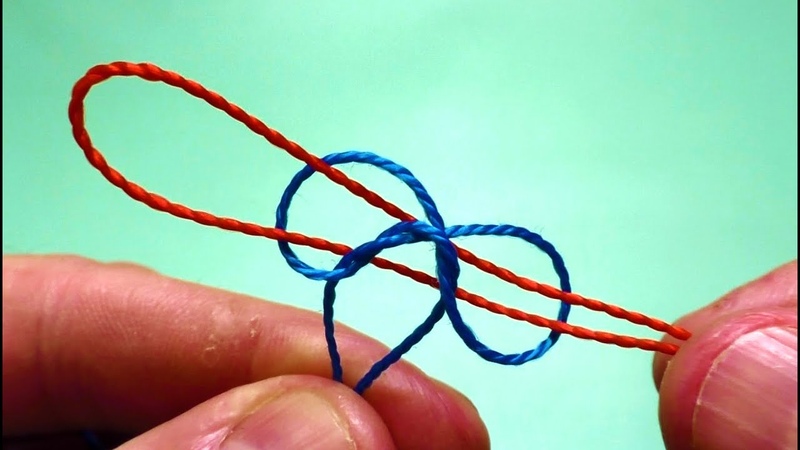

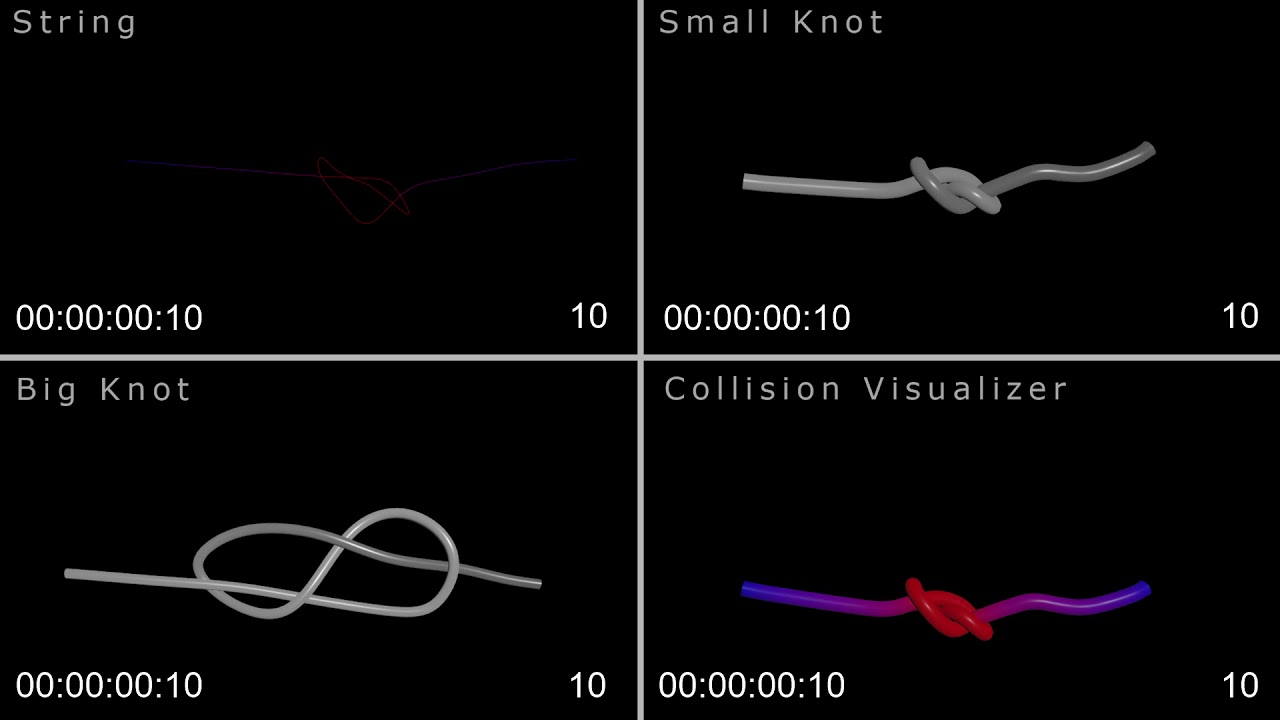

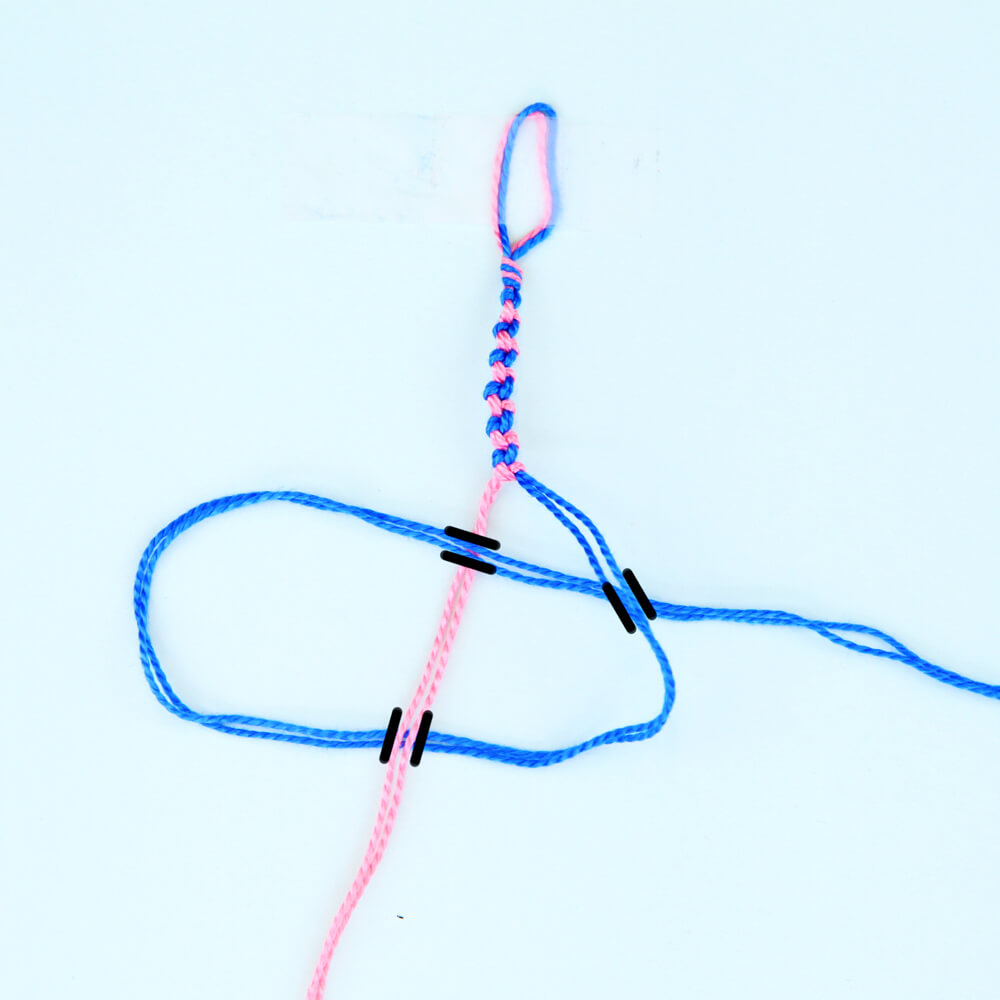

Step 1: Put a stopper knot in the end of

one rope. The trick with stopper knots is to form two loops, the second

behind the first, and feed the tail back through both. Step 2:

Before you tighten the knot, pass the end of the other rope through both

loops as shown.

Step 3: Now form another stopper knot, this time with the

second rope, wrapping your loops around the first line.

Steps 4 & 5: Tighten both knots and draw them snug against

each other. Leave plenty of tail (probably more than pictured), to account

Leave plenty of tail (probably more than pictured), to account

for any slippage.

It’s hard to

describe in words. Be very sure you’ve got it right before abseiling down.

I strongly suggest you get someone experienced to teach you this knot, in

person, so they can verify you’ve got it right. The consequences of a

mistake, when using this knot to join two ropes for abseil, are naturally

going to be very serious indeed. Furthermore, its easy to stuff this up, especially if

its cold, dark and wet and you’re looking to bail in a hurry, so perhaps

this is not the best method to employ, though it certainly works if done

correctly. The knot can also be difficult to undo once you’ve weighted it.

Above

Right: The double fisherman’s used to join the ends of some accessory

cord to form a loop, suitable for friction knots such as the Prusik,

etc.

Overhand Knot

The

overhand knot is probably the simplest and fastest knot you can form to

join two ropes together for abseil. This can be very handy in situations

This can be very handy in situations

where speed is critical to safety. It’s also generally believed to be the

least likely knot to get stuck when the ropes are pulled. But how scary

does it look? Even with the recommended super long tails, the knot can take some

getting used to.

The theory with this

knot is that it will slide flat against the rock and flip over an edge

rather than jamming. (See picture right, and check out Petzl’s

page explaining the concept).

Follow

these steps to form an overhand knot to join two ropes:

Step 1: Grab an end of each rope and form the simple pass shown

above. Step 2: Pull tight, leaving a large amount of tail (ie.

about a metre) for both ends, to account

for any slippage. It shouldn’t slip too greatly if the ropes are of the same

diameter, but this is not something to skimp on. You should probably leave

You should probably leave

more tail than the pictures above imply.

Note

comments such as “The Overhand Knot should not be used

on tape due to progressive cyclic slippage.” and “There may be

an issue with the strength of the Overhand Knot when used on older rope.”,

appear in research articles

from the Bush Walkers Wilderness Rescue.

Reader’s Feedback

From Kieran Loughran:

1. If you are doing a multi-abseil retreat using two ropes of equal diameter

then the overhand knot is more secure than an figure-8

2. Use a double-fisherman knot to join ropes of unequal diameter for

multi-abseil descents.

3. If you are using two ropes as a fixed line, first join them with a

double-fisherman knot and then tie an alpine butterfly knot that

incorporates the double-fisherman knot in the loop. That gives you three

things 1. A bomb-proof knot; 2. A built-in safety loop to clip on the knot

A bomb-proof knot; 2. A built-in safety loop to clip on the knot

changeover; 3. Knots that are easy to untie (unless you had to weight the

safety loop, in which case you won’t care).

Further Reading:

Preferred Knots For Use In

Canyons – Documents actual testing of Tape, Double Fisherman’s,

Overhand for rope and tape, Rethreaded Figure 8, Abnormal Figure 8 and

Alpine Butterfly from Bush Walkers Wilderness Rescue web site.

Abseil

Knots – Further testing and warnings against the abnormal figure eight

knot on Needle Sports site.

Double Fisherman’s

– From University of New England Mountaineering Club.

Overhand knot

– From Petzl’s web site.

Figure Eight With A Loop – Also from Petzl’s web site.

Dawn’s

FAQ – For rec.climbing discussions and arguments about the best knot to

use when joining two ropes for an abseil.

How

To Deal With Stuck Ropes – From Climbing Magazines Tech Tips.

Rope And Gear

Testing – Results of pull tests on various knots joining different

ropes.

EDELRID Knot Tests

– Results of testing double fisherman’s, and EDK, etc. Unfortunately much

of the text is in German.

Home | Guide | Gallery | Tech Tips | Articles | Reviews | Dictionary | Forum | Links | About | Search

Chockstone Photography | Landscape Photography Australia | Australian Landscape Photography

Please read the full disclaimer before using any information contained on these pages.

All text, images and video on this site are copyright. Unauthorised use is strictly prohibited.

No claim is made about the suitability of the information on this site, for any purpose, either stated or implied. By reading the information on this site, you accept full responsibility for it’s use, and any consequences of that use.

Stringed musical instruments

Category: Musical instruments

In the class of acoustic instruments, strings are the most widely used. This is due to the demand for them from all consumer groups. Their use is universal: in the concert hall (in ensembles and solo), for home music-making and in field conditions.

The leading role in the assortment of string instruments belongs to plucked instruments, which is explained by their small weight and dimensions, satisfactory sound range, expressive timbre, high level of reliability and maintainability.

Plucked instruments are distinguished by the number of strings, the sound range, the intervals between the sounds of open strings, the shape of the body, the exterior finish, the design of the main components.

Plucked instruments include: guitars, balalaikas, domras, mandolins, various national instruments (psaltery, banduras, cymbals, etc.).

The harp is also a plucked instrument, a very complex multi-stringed instrument designed for large symphony orchestras. They are released in limited quantities.

They are released in limited quantities.

The guitar is the most popular plucked instrument. There are the following types of guitars: Spanish, Russian, Hawaiian. The Spanish (South European) six-string guitar is considered classical. By the number of strings, guitars are: twelve-, six-, seven-string. The most widespread are seven- and six-string.

Depending on the length of the working part of the string (mensur), the following types of guitars are distinguished: large (concert), normal (men’s), reduced sizes – tertz (ladies’), quart and fifth (school). Downsized guitars are named for the interval they sound higher than normal guitars. In table. the length of the scale of the above types of guitars is given.

Seven-string guitar (Russian) has a sound range from З 1 /4 to

З1/ 2 octaves from the D of the big octave to the la of the second octave. The six-string guitar has a range from E of the big octave to A-sharp of the second octave.

Hawaiian guitars have very limited use, mainly for concert activities. They have a melodious, vibrating sound. Range – 3 / 2 octaves.

The guitar consists of the following main components: body with shells, tongs, soundboard, bottom, springs, bridge, covers, neck and peg mechanics.

The body is designed to amplify the sound vibrations of the strings.

It is shaped

figure eight and consists of a flat top (1) and a slightly convex bottom deck – the bottom (2). The decks are interconnected by two right and left shells (9), the ends of which are attached from the inside to the upper (6) and lower (7) tongs. Counter-shells (8) are glued to the shells, creating the necessary area for gluing the decks. Shells, counter-shells and tongs form the body frame. To the inner surface of the decks, in their middle part, springs (17) are glued – bars of various sections, which serve to create the necessary resistance to string tension and uniform propagation of sound vibrations.

The sound hole (15) of the guitar is round, somewhat larger than other plucked instruments. Below the resonator hole (socket), a support (12) is fixedly glued, which has holes and buttons for fixing the strings (19).

The neck is the most important knot; the convenience of the game depends on how correctly its width, thickness and profile of the oval are chosen. The neck of the guitar (4) is wide, its lower thickened part is called the heel. A hole is drilled in the heel for the connecting screw. At the top of the neck is a wooden or bone nut (11) with slots for the strings. The saddle is located on the stand (12) for the strings. The distance between the nut and saddle is called the scale of the guitar. The headstock has a mechanism with pegs (21) to secure the strings.

The neck of the guitar, like all plucked instruments, is divided into parts – frets with fret plates cut into it from brass or nickel boron

wire.

The division of the neck into beats must be accurate. Fret breaking is based on the principle of changing the length of the working part of the string. The length of each fret should be such that, shortening the length of the string by this amount, the pitch would change each time by half a step, i.e., the breakdown of the frets is based on obtaining a twelve-step equal temperament system. Fret spacing accuracy is one of the most important indicators of the quality of instruments; violation of the fretboard splitting rule makes it impossible to tune the instrument and play it.

Fret breaking is based on the principle of changing the length of the working part of the string. The length of each fret should be such that, shortening the length of the string by this amount, the pitch would change each time by half a step, i.e., the breakdown of the frets is based on obtaining a twelve-step equal temperament system. Fret spacing accuracy is one of the most important indicators of the quality of instruments; violation of the fretboard splitting rule makes it impossible to tune the instrument and play it.

Guitars are available in regular, premium and premium quality. They differ in the materials used and the quality of the finish.

The body of the guitar is made of birch or beech plywood, the neck is made of hardwood – maple, beech, birch; fretboard – pear, ebony, beech; sills – from hornbeam, plastic, bone; stand – made of beech, maple, walnut, plastic; arrow – from beech, birch, maple; strings – steel, bass – are wrapped with a cantle. Large guitars use nylon strings.

Balalaika is an old Russian instrument with a sharp, piercing timbre, used for solo performance and playing in stringed orchestras. Balalaikas are produced in two varieties: three-stringed prima, four-stringed (with the first paired string), six-stringed (with all paired strings) and orchestral three-stringed – second, viola, bass, double bass, differing in scale length:

♦ prima – with a scale length of 435 mm;

♦ second – 475 mm scale length;

♦ alt – with a scale length of 535 mm;

♦ bass – 760mm;

♦ double bass – 1100 mm.

Balalaika prima – the most common, common, used as a solo and orchestral instrument. It has significant musical and technical capabilities.

Balalaikas second, viola, bass and double bass are used in orchestras and are called orchestral instruments. The second and viola are mainly accompanying instruments.

All types of balalaikas are in quarters.

Balalaikas from prima to double bass make up the balalaika family. Sound range from 1 3 / 4 to 2 1 / – octaves.

Sound range from 1 3 / 4 to 2 1 / – octaves.

Balalaikas, like mandolins, domras, have many parts and units of the same name with guitars.

Balalaika consists of body, neck and head. The body of the balalaika is triangular in shape, the bottom is slightly convex, ribbed, made up of separate rivet plates. The number of rivets can be from five to ten (12, 13, 14). The rivets in the upper part of the body are attached to the upper collar (5) and connected

with a neck.

Family of orchestral balalaikas

From below, the rivets are glued to the back (10), which is, as it were, the base of the instrument. Seagulls (7) are glued along the perimeter, giving the body rigidity. A resonant deck (8) is placed on the contra-beam, consisting of several specially selected resonant spruce boards. In custom instruments, a tuned deck is used, that is, a deck that sounds in a certain tone. The deck has the shape of an isosceles triangle, the base of which is straight, and the sides are somewhat curved. A resonator hole-rosette is cut out in the soundboard, having an ornament in the form of a circle or a polyhedron made of mother-of-pearl, plastic, valuable wood. On the right side, the deck is covered with a shell (18), which protects it from damage. Small strips-springs (6) are glued to the inside of the deck, giving it elasticity and increasing the purity of the sound. Below outlet (19) a movable stand is installed on the soundboard, which transmits the vibrations of the strings to the soundboard. The stand determines the height of the strings above the fingerboard and limits the working length of the strings. The connection between the soundboard and the body is covered with a lining. On the edge of the deck in the lower part of the body is

A resonator hole-rosette is cut out in the soundboard, having an ornament in the form of a circle or a polyhedron made of mother-of-pearl, plastic, valuable wood. On the right side, the deck is covered with a shell (18), which protects it from damage. Small strips-springs (6) are glued to the inside of the deck, giving it elasticity and increasing the purity of the sound. Below outlet (19) a movable stand is installed on the soundboard, which transmits the vibrations of the strings to the soundboard. The stand determines the height of the strings above the fingerboard and limits the working length of the strings. The connection between the soundboard and the body is covered with a lining. On the edge of the deck in the lower part of the body is

saddle (11). The glued neck is integral With the body, it has the same function as the guitar neck,

the headstock (1) with the peg mechanism (25) is attached to the neck. The peg mechanism has worm gears for tensioning and tuning the strings (22). Along the entire neck, at a certain distance from one another, small transverse metal plates are cut, protruding above the neck and dividing it into frets (23).

Along the entire neck, at a certain distance from one another, small transverse metal plates are cut, protruding above the neck and dividing it into frets (23).

Sounds are extracted by plucking with fingers, less often by striking. mediator. The mediator is a special flat oval plate, it is made of plastic or tortoise shell. Tortoiseshell picks are considered the best.

According to the exterior finish and materials used, balalaikas are produced in ordinary and high quality.

The body staves of balalaikas are made of hard hardwood – maple, birch, beech. Sometimes they are made pressed from wood fiber pulp.

The back is made of spruce, lined with birch or beech veneer; deku – from straight-grained, well-dried resonant spruce; stand on the deck – beech or maple. Corners are made from stained maple and birch veneer; dumplings – from spruce. On the shell is stained birch, maple veneer or pear.

The neck is made of hard woods – maple, beech, hornbeam, birch; fretboard – stained maple, hornbeam, pear or ebony; dots on the neck – made of plastic or mother-of-pearl; fret plates – made of brass or nickel silver; nut and nut – from hornbeam, ebony, plastic, metal and bone; strings are steel. For low-pitched instruments, the strings are wrapped with copper wire; vein and synthetic strings are also used.

For low-pitched instruments, the strings are wrapped with copper wire; vein and synthetic strings are also used.

Balalaikas of special and individual production differ from the usual orchestral musical instrument in terms of sound strength and timbre features, external finishing of details and selection of wood species.

Domra is a Russian folk instrument, unlike the balalaika, it has a less sharp and softer and more melodious timbre.

Domras produce three-string fourths and four-strings fifths. Domra sound range from 2/ 2

up to Z1/ 2 oct.

Depending on the size, a family of domra is made, the length of the scales of which is presented in table.

Domra is used for solo playing and in string orchestras.

Characteristics of the domra family are given in Table.

Domra, like the balalaika, consists of a body and neck, tightly connected.

Domra differs from the balalaika in its rounded “pumpkin” body. It consists of seven to nine bent rivets, the ends of which are attached to the upper and lower collars, a deck with a rosette, a shell, counter-beams, springs, and a movable stand.

It consists of seven to nine bent rivets, the ends of which are attached to the upper and lower collars, a deck with a rosette, a shell, counter-beams, springs, and a movable stand.

The neck of the domra is longer than that of the balalaika; at the domra they put three or four strings, fixed with the help of a string holder. Domra is made from the same materials as balalaikas.

According to the quality of the finish and the materials used, domras are distinguished between ordinary and high quality.

Mandolin is a popular folk instrument: together with guitars, mandolins make up the Neapolitan orchestra; it has a bright and melodious timbre. Mandolins are produced oval, semi-oval and flat. The different construction of the body of the instruments gives them a specific timbre of sound.

The body of the flat mandolin consists of a shell, upper and lower tongs, deck, bottom, springs, pointer. The parts are made from the same materials and have the same purpose as similar guitar body parts.

The body of a semi-oval mandolin consists of a slightly convex bottom (glued from 5-7 staves or bent plywood), shells, counter-ribs, upper and lower tongs, arrow, soundboard, spring, lining, tailpiece. It is made from the same materials as the parts of the guitar.

Pear-shaped oval mandolin. Consists of rivets (from 15 to 30), cleats, counter-strings, springs, side, trim and string holder; barrels of extreme, wider staves; figured shield, soundboard, which at a distance of 3-4 mm below the stand has a break, necessary to increase the pressure of the strings on the soundboard.

The neck is usually integral with the body, but can also be detachable.

The head of the mandolin has eight pegs (four on each side). The purpose and name of the parts are the same as the parts of the guitar. When extracting sounds, a mediator is used.

Oval mandolins have a nasal tone. Semi-oval sounds more bright with a less pronounced nasal tint. Flat mandolins sound more open and harsh. In table. given, the main data of the above mandolins

In table. given, the main data of the above mandolins

The mandolin family is produced: piccolo, alto (mandola), lute, bass and double bass.

Mandolin sound range 3 1 / 3 octaves.

According to the quality of the finish and the materials used, mandolins are distinguished between ordinary and high quality.

Harp – a multi-stringed instrument (46 strings), is part of the symphony orchestra and many instrumental ensembles; in addition, it is often used as a solo and accompanying instrument.

The harp is a triangular frame with strings stretched between its two sides. The underside of the frame, to which the strings are attached, is shaped like a hollow box that serves as a resonator. The body of the harp is usually richly decorated with carvings, ornaments and gilding.

The harp is tuned in a major scale. The restructuring of the scale to other keys is carried out by switching the pedals located at the base of the harp. To guide the musician when playing, the C and F strings in all octaves are colored red and blue.

To guide the musician when playing, the C and F strings in all octaves are colored red and blue.

The range of the harp must be 6/ 2 octaves, ranging from D-flat contra-octave to G-sharp fourth octave.

Limited production of harps.

Banjo is the national instrument of American Negroes, which has recently gained popularity in variety ensembles of our country.

The banjo consists of an annular body-hoop, tightened on one side

skin that serves as a deck. For adjusting deck tension and tuning

use special screws. The neck and head of the instrument are conventional. steel strings,

play them as a mediator. The number of strings and their tuning may be different.

depending on the size and type of banjo. The appearance of the banjo is presented on

Spare parts and accessories

Spare parts and accessories for plucked instruments are: strings for each instrument (single or in sets), peg mechanism, string holders, stands, picks (plectrums), cases and covers.

Stringed musical instruments

IN

class of acoustic instruments

are most widespread

strings. This is due to the demand for

them in all consumer groups. Application

they are universal:

concert hall (in ensembles and solo),

for home music making and camping

conditions.

In assortment

stringed instruments leading role

belongs to plucked instruments, which

due to their small weight and

dimensions, satisfactory

range of sound, expressive

timbre, high level of reliability

and maintainability.

Plucked

tools

distinguished by the number of strings, range,

sounds, intervals between sounds

open strings, body shape, external

finishing, construction

main nodes.

TO

plucked instruments include: guitars,

balalaikas, domra, mandolins, various

national instruments (harps, banduras,

cymbals, etc.).

Guitar

is the most popular plucked instrument.

There are the following types

guitars: Spanish, Russian, Hawaiian.

Spanish is considered classical

(South European) six-string

guitar. By the number of guitar strings

there are: twelve-, six-, seven-string,

The most widespread

seven and six strings.

IN

depending on the length of the working part

strings (scales), distinguish guitars

the following types: large (concert),

normal (male), reduced

sizes – tertz (ladies), quarts and quints

(school).

Varieties | scale length, |

Normal six-string | 650 |

Big | 650 |

Tertz | 610 |

Quart | 585 |

Quint | 540 |

Variety | tone character, |

Seven-string | Juicy, velvety, |

Tertz | Less deep |

Quart | Less deep |

Six-string | Timbre, like |

Hawaiian | Compared with |

The guitar consists of

the following main units: housings with

shells, toggles, shooters, decks, bottom,

springs, stands, covers, neck and

peg mechanics.

Housing

intended

to amplify the sound vibrations of the strings.

setting,

setting,